Analysis

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

-

Available versions :

EN

Corinne Deloy

On 6 November 2024, outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz (Social Democratic Party, SPD) dismissed his Finance Minister Christian Lindner (Liberal Democratic Party, FDP), which led to the departure of the FDP ministers from the “Ampel” coalition he led, the first in history to include three parties (SPD, Greens and FDP). Olaf Scholz has since headed a minority government. Over the last two years, the tensions between the three partners in the government have become significant and have developed into truly fundamental disagreements. The 2025 budget was the trigger for the final crisis: Olaf Scholz had expressed his wish to temporarily derogate from the debt brake mechanism (Schuldenbremse) introduced into the Basic Law in May 2009, which prohibits any deficit in excess of 0.35% of GDP, a measure which the FDP opposed. The three parties in government were at loggerheads over economic policy: the outgoing Chancellor supported increased social spending, the Minister for the Economy and Climate Robert Habeck (Greens) had called for greater investment in the ecological transition, and the Minister for Finance defended a policy of savings and tax cuts. This tension between a supply-side policy aimed at creating a favourable environment for economic activity and a demand-side policy aimed at strengthening the welfare state has often been the cause of the downfall of governments in Germany.

On December 5, Olaf Scholz lost the confidence of the Bundestag, by 394 votes to 207, with 116 abstentions, paving the way for the dissolution of the Lower House of Parliament and the calling of snap (seven-months ahead of time) federal elections. These were set for February 23. The tabling of a motion of confidence in the Bundestag is a very rare event in Germany, having taken place only four times since 1945. In September 1972, Chancellor Willy Brandt (SPD) lost his majority in the Bundestag, only to regain it in the November elections. Ten years later, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (SPD) also lost his majority. He was replaced by Helmut Kohl (CDU). In 2001, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (SPD) tabled a motion of confidence, but the Lower House renewed its support of him. In July 2005, however, he submitted another motion of confidence, which was rejected, and he was replaced by Angela Merkel (CDU).

Once a motion of confidence has been rejected, the Federal President has 21 days in which to dissolve the Bundestag. This right of dissolution lapses if the Lower House elects a Chancellor by a majority of its members. If this is not the case, federal elections must be held within sixty days of the dissolution (Article 39 of the Constitution).

According to the INSA opinion poll, Christian Democratic Union (CDU), led by Friedrich Merz, is likely to come out ahead on February 23, albeit with one of its weakest results (30% of the vote). Far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), led by Alice Weidel, is expected to take second place with 21%, ahead of SPD with 16%. The Greens, led by Felix Banaszak and Franziska Brantner, are projected to win 12%, while Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht-Für Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit, BSW), a radical left-wing party born of a split from the Left Party, is projected to win 7%.

FDP and Left Party (Die Linke) are due to fall short of the 5% threshold required for representation in the Bundestag. The future Lower House should therefore reflect the fragmentation of the German political landscape, which is becoming increasingly marked over the years.

The European elections of June 9, 2024 saw CDU/CSU win with 30.02% of the vote ahead of AfD, 15.89%, and SPD (13.94%). This was its weakest result since the first European elections in 1979.

CDU/CSU would like to avoid having to form a three-party coalition, and could ally itself with the Greens, but could also choose to form a “grand coalition” with the SPD, at the risk of this party falling even further in voting intentions.

“Germany is in the grip of doubt, the German model is in crisis,” says Claire Demesmay, a researcher at the Marc Bloch Center in Berlin. The country, once a model of stability, is in serious crisis. It has been in recession for two years (-0.3% in 2023 and -0.2% in 2024), and statistics forecast GDP growth of 0.2% for 2025. Numerous flagship companies have announced restructuring plans: ThyssenKrupp Steel, which is set to cut 5,000 jobs; Volkswagen, which plans to close three of its plants and reduce its workforce by more than 35,000, as well as BASF, Ford and Bosch. “Germany needs to thoroughly overhaul an obsolete model based on cheap energy supplied by Russian gas, exports to China and the security guarantee provided by the United States,” says Shahin Vallée, a researcher at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP).

AfD's result in the spotlight

In a Germany in crisis, Olaf Scholz's future as head of government seems in jeopardy, and CDU leader Friedrich Merz is the favourite for the chancellorship. However, all eyes are on Alice Weidel (AfD), whose party takes a hard line against immigration and Islam. It is hostile to the theory of global warming (and is calling for the demolition of wind turbines). AfD is in favour of Germany's exit from the European Union and the return of the Deutsche Mark. Economically liberal, it supports market deregulation. Pacifist, it opposes NATO and is calling for a halt to arms deliveries to Ukraine, the opening of negotiations with Russia and the resumption of Russian gas purchases. “Choosing to entrust Germany's destiny to Friedrich Merz means choosing war”, Alice Weidel repeats.

AfD is particularly well-established in the eastern part of the country. This was particularly evident in the elections held in September 2024 in three Länder. In Brandenburg, AfD came 2nd (31.52% of the vote and 30 seats) behind the SPD (33.57% of the vote and 32 seats); in Saxony, AfD won 33.96% of the vote (40 seats), ahead of the CDU (34.43% and 41 seats). However, AfD came out ahead in Thuringia, winning 34.33% of the vote (and 32 seats) ahead of the CDU (33.48% of the vote and 23 seats).

Whatever its outcome on February 23, AfD is unlikely to win office for lack of a coalition partner. All the governing parties have ruled out working with AfD, and the German political system implies the formation of a coalition and therefore the possibility of compromise, which is not in the DNA of radical forces. However, if the party were to take 2nd place and thus become the main opposition force, Germany would be in for a real earthquake.

On December 28, American billionaire Elon Musk, who has been asked by US President Donald Trump to head the Commission on Government Efficiency in Washington, published an op-ed in the Sunday edition of the daily Die Welt, claiming that AfD was “the last ray of hope for Germany”. “Only AfD can save Germany”, he wrote, deeming the country ‘on the brink of economic and cultural collapse’. The boss of X, Tesla and SpaceX, considered the richest man in the world, approves of AfD's controlled immigration policy, its desire to cut taxes and deregulate the market. Accused of interfering in German politics, Elon Musk justified himself by arguing that he owns a Tesla mega-plant near Berlin and is a major investor in the country. On January 9, Elon Musk broadcast, live on X, a discussion-debate between himself and Alice Weidel. “AfD couldn't have imagined a better campaigner in its ranks, as his image as a successful entrepreneur legitimizes the far-right party among Germany's traditional conservative electorate, who were previously sceptical of his economic programme,” points out political communications expert Johannes Hillje. “Elon Musk is now working hand in hand with Donald Trump, who has been re-elected president of the United States. This sends a clear message to voters: AfD could become a credible interlocutor for Washington,” said Paul Maurice, Secretary General of the Comité d'études des relations franco-allemandes (CERFA). On January 25, Elon Musk once again spoke (on video) at an AfD election rally, calling on Germans to “be proud to be German” and “not to get lost in multiculturalism”. “Children shouldn't be guilty of their parents' sins, let alone those of their great-grandparents. There is too much emphasis on guilt for the past, and we have to get past all that,” said the X boss, whose gesture resembling a Nazi salute at Donald Trump's inauguration on January 20 is still causing controversy. “AfD must fight (...) in particular for more self-determination for Germany and the countries of Europe and less Brussels,” he further declared. “Alice Weidel allows AfD to present a more respectable face to voters,” emphasized Gerd Mielke, a political scientist at Mainz University. She is confident that conservatives will join her in her calls to halt immigration. “With her, the normalization of AfD is underway, and should help it to one day reach 30% of the vote. In 2029, she could be in a position to form a government with the conservatives,” says Gerd Mielke, adding: “But she will be the chancellor”. On January 25, Germans took to the streets in several of the country's major cities to say “no” to the far right. There were 40,000 in Cologne and 35,000 in Berlin, according to police figures.

The attack on a group of children by an asylum seeker on January 22, 2025, which left two dead including one child, can only add fuel to AfD's fire. The party has no problem denouncing the current government's inability to ensure the safety of the population. In addition, the nationality of the murderer, an Afghan living without legal status, is being exploited and highlighted. This attack follows on from those at the Mannheim market in May (one dead), perpetrated by an Afghan refugee, and at the Solingen festival in August (three dead), perpetrated by a Syrian with subsidiary protection status, as well as that at the Magdeburg Christmas market (six dead), perpetrated by a Saudi refugee in December.

Alice Weidel claims that if she comes to power, AfD will “close the borders completely” and carry out mass deportations of foreigners or people of foreign origin. “We need remigration if we are to live safely in Germany,” she repeated at a rally on January 25.

Can Olaf Scholz hope for another miracle?

Olaf Scholz was unanimously elected as the SPD's candidate for chancellor on November 25, but he is still Germany's most unpopular leader. He has not capitalized on his time in power, as is usually the case. Even within his own party, since an opinion poll conducted by Infratest Dimap institute, revealed on November 21 that 60% of Germans considered Boris Pistorius to be the best candidate for the chancellorship, compared with 21% who preferred Olaf Scholz. The weekly Der Spiegel claimed that Olaf Scholz was the weakest candidate the SPD had ever put forward. “Olaf Scholz is a damaged candidate whose bid raises doubts. He is going into the campaign weighed down by this burden at the head of a coalition that has collapsed,” said Stefan Marshall, professor of political science at the University of Düsseldorf. However, Olaf Scholz has always been underestimated. In fact, he caused a surprise at the federal elections on 26 September 2021 by winning ahead of the CDU, although it should be noted that Armin Laschet, the Christian Democrat candidate, made a series of blunders during the campaign, which caused his lead in the polls to dwindle as the weeks went by. Today, the outgoing Chancellor looks as though he could be in with a chance again, particularly if he manages to run a campaign focused on defending social benefits. Olaf Scholz has had to come to terms with the record of his predecessors, particularly their choices on energy. Former Chancellor (2005-2021) Angela Merkel (CDU) chose Russian gas as a transitional energy source when Germany was phasing out nuclear power. Berlin had to give up Russian gas after Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, a decision that has contributed to a sharp rise in electricity prices.

In 2023, Robert Vehrkamp and Theres Matthiess drew up a progress report on the coalition government's term of office at the request of the Bertelsmann Foundation and believe that the judgement of Olaf Scholz's term of office should not be as harsh in a while. In their view, the main social and societal measures in the Social Democrat candidate's programme have been implemented rapidly: the minimum wage has been raised to €12 an hour (€9.6 in 2021), unemployment benefit has been raised and reformed, family allowances have been increased, the retirement age has been frozen, and retirement pensions have been indexed. In addition, Germany has, for the first time in its history, achieved the target set by NATO of allocating 2% of GDP to defence.

Olaf Scholz is defending a programme proposing a demand-side policy and an increase in social subsidies. He wants to raise the minimum wage to €15/hour by 2026, reduce VAT on food products from 7% to 5%, cut taxes for the poorest citizens, reform inheritance tax and introduce a wealth tax for people with assets in excess of €10 million. The outgoing Chancellor has made the fight for jobs his priority. He defends maintaining the retirement age (between 65 and 67). He wants to reform the state debt brake mechanism. Olaf Scholz is advocating the introduction of a bonus to attract investors to Germany. This measure would grant a refund in the form of a tax credit amounting to 10% of the sum paid to any German or foreign company investing in industry. The aim is to create a €100 billion fund to finance the public investment needed to upgrade the country's energy, digital, rail and other structures.

Finally, Germany is one of Ukraine's main arms suppliers. Olaf Scholz is nevertheless presenting himself as a man of restraint in his military support for Kyiv. He is hoping to capitalise by presenting himself as the ‘Chancellor of Peace’ and is promoting the path of caution to avoid any military escalation with Russia. The outgoing Chancellor is calling for a reduction in military support for Ukraine. For the time being, he is opposed to Kyiv receiving a new €3 billion military aid package. In total, Germany has given nearly €40 billion to Ukraine, the second largest amount after the United States. The country has taken in 1.2 million Ukrainians as refugees.

Liberal Democrats struggling

A partner of the SPD for more than two years at the head of state, the FDP could well be punished not only for bringing down the government, but also for planning its downfall and trying to pass itself off as its victim. Former Finance Minister Christian Lindner, who made a series of provocative proposals to push the Chancellor out of office, subsequently accused Olaf Scholz of planning his ouster. The recent revelation of a plan drawn up by the FDP to bring down the coalition led by Olaf Scholz has weakened the Liberal Democrat party. The document, entitled D Day - the name given to the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, a detail that has been little appreciated - describes how the break-up with Olaf Scholz was to take place, the ideal moment for it to be triggered and even the language that was to accompany the event, including Christian Lindner's speech on his departure. Following the publication of the affair on 29 November, party secretary general Bijan Djir-Sarai and federal director Carsten Reymann resigned. The FDP's setbacks could ultimately benefit the CDU.

Christian Democratic Union's predicted victory

Friedrich Merz took over as leader of the CDU in January 2022. Since then, he has succeeded in calming the party by putting an end to internal quarrels. ‘Friedrich Merz has shaped the party by changing its ideological base. The CDU is more socially conservative than in Angela Merkel's time, particularly on immigration and gender issues, and more economically liberal. Friedrich Merz, who is more liberal and conservative than Angela Merkel, is therefore the ideal candidate to lead this programme, which is more like what the CDU was before Angela Merkel’, said Uwe Jun, Professor of Political Science at the University of Trier. The Christian Democrat leader wants to break with Chancellor Merkel's legacy, deeming her too close to the SPD and criticising her for opening the country up to more than a million people fleeing war from Syria and Afghanistan in 2015-2016. Asylum applications rose to 900,000 in 2015; they were forecast to total 213,000 in 2024. Under Friedrich Merz, CDU is returning to traditional values and adopting a tougher stance on immigration in a bid to contain the rise of AfD. Alice Weidel has accused Friedrich Merz of copying her programme.

Angela Merkel was always suspicious of Friedrich Merz, whom she drove from office by ousting him as head of CDU parliamentary group in 2002. Friedrich Merz left the party in 2009. During his years away from politics, Friedrich Merz worked as a lobbyist and private wealth manager. He was a member of the board of directors of several companies (the HSBC bank, the German subsidiary of the Blackrock asset manager, the Cologne-Bonn public airport). He is now accused of never having held office as a mayor or regional councillor, and of never having been a member of a regional or federal government.

The CDU party is advocating a supply-side policy to enable Germany to return to growth. With its Agenda 2030 programme, the party is aiming for 2% GDP growth ‘in the medium term’. The recommended means of achieving this Tax relief measures. The party supports tax cuts for the most affluent and for businesses in order to boost competitiveness, and wants to cut taxes, particularly on inheritance and capital, reduce the tax burden on businesses by 25%, make overtime tax-free and change the income tax scale. ‘You are leaving the country in one of the worst economic crises it has ever experienced since the end of the war’, said Friedrich Merz to outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz. However, the desired policy of tax cuts is costly. According to calculations by the German Economic Institute (IW), it would cost around €90 billion a year. ‘This will be a major hole in the federal budget’, said Martin Werding, a member of the German Council of Economic Experts and Professor of Social Policy and Public Finance at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB).

Friedrich Merz wants to make work financially attractive, and even to transform the labour market. He wants to create a Federal Digital Agency for Skilled Immigration to recruit the talent that Germany will need and that it is likely to lack, since according to figures, the German working-age population is set to fall from 52 to 43 million by 2050. He wants to reduce the number of civil servants and simplify administrative procedures. While he is not saying no to reforming the government's debt brake mechanism, he is first calling for a reduction in government social spending on migration and family policy. The Christian Democrats also want to review energy policy and, for example, lift the ban on combustion engines by 2035. They have stated that they will reconsider the priority given to the climate in economic policymaking. A few days ago, however, Friedrich Merz reversed his decision to bring the country's nuclear reactors back into operation. He announced ‘a fundamental change’ to Germany's immigration rules if he comes to power. He promised to strengthen internal security by ordering ‘controls at all national borders’, to tighten up migration policy and asylum procedures. He is favourable to outsourcing asylum applications to third countries. ‘We are standing in the rubble of ten years of misguided asylum and immigration policy in Germany’, he said.

The German Political System

The German Parliament is bicameral, comprising of a lower house, the Bundestag, and an upper house, the Bundesrat. Elections for members of the Bundestag are held every four years using a mixed system that combines first-past-the-post and proportional representation voting. Each voter has two votes. The first (Erststimme) is used to elect the member of parliament for the constituency (Wahlkreis) in which he or she lives. There are 299 constituencies in the country and the number of MPs elected in this way, who thus obtain a direct mandate, ranges from two in Bremen and four in Saarland to 64 in North Rhine-Westphalia. The second (Zweitstimme) allows voters to cast a preferential vote for a list presented by a political party at Land level (Germany has 16 Länder).

The electoral law was amended in March 2023 and the Bundestag now comprises a fixed number of 630 MPs (MdB). The number of members elected to the lower house had been rising steadily: 603 in 2002, 614 in 2005, 622 in 2009, 631 in 2013, 709 in 2017 and... 736 in 2021.

Previously, only parties that obtained more than 5% of the votes cast at national level or three direct mandates in single-member constituencies could be represented in the Bundestag. If, in a Land, a party won more direct mandates than the number of seats allocated to it on the basis of the number of ‘2nd votes’, it nevertheless retained these surplus mandates (Uberhangmandate), which explains why the number of members of the Lower House varied from one election to the next. From now on, only the ‘2nd vote’ percentage will be taken into account, which means that some MPs who finish first in their constituency may not enter the Bundestag if their party gets under 5% of the national vote. The main argument put forward by the supporters of the reform is budgetary. The new electoral law should result in savings of €310 million. In 2023, the cost of running the Lower House was €1.14 billion (736 elected members), compared with €857 million in 2016 (631 deputies).

Seats are allocated using the Sainte-Laguë/Schepers method. The percentage of 2nd votes determines the number of seats proportionately allocated to each party and, ultimately, the balance of power between the parties in the Bundestag. Parties representing recognised national minorities (Danes, Friesians, Swabians and Roma) are exempt from the requirement to achieve at least 5% of the vote to be represented in the Bundestag.

The German electoral system aims to ensure that the party has a stable parliamentary majority and to avoid the fragmentation of the political scene that the country experienced under the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), when the large number of political parties represented in parliament made it virtually impossible to form a government. In 1949, 11 political parties were represented in the Bundestag, in 1957 only 4, and between 1961 and 1983 only 3 (SPD, CDU/CSU and FDP). In 1983, the Greens managed to break the 5% barrier in terms of votes cast and enter parliament; they were followed in 1990 by the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), which emerged from the Socialist Unity Party (SED) of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), the forerunner of the Left Party (Die Linke) - the former Communist MPs entered the Bundestag one year after the fall of the Berlin Wall - and, in 2013, the Alternative for Germany.

8 political parties are represented in the current Bundestag:

- Social Democratic Party (SPD), under outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz, founded in 1863 and led by Lars Klingbeil and Saskia Esken, is Germany's oldest political party. It has 208 MPs;

- Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the main opposition party founded in 1945 and led by Friedrich Merz, has 152 seats;

- Christian Social Union (CSU), led by Markus Söder, has been cooperating with the CDU since 1953. According to their agreement, the CDU does not present a candidate in Bavaria and the CSU competes only in this Land. It has 55 seats;

- Greens/Alliance 90 (Grünen), formed in 1993 when Alliance 90, the civil rights movement of the former GDR, merged with the Green Party. Members of the outgoing government coalition and led by Felix Banaszak and Franziska Brantner, they have 118 elected members;

- Liberal Democratic Party (FDP), founded in 1948 and led by Christian Lindner, has long been the kingmaker of elections. A member of the outgoing government coalition until November 2024, it has 92 seats;

- Alternative for Germany (AfD), founded in spring 2013, is a far-right party. Led by Alice Weidel and Tino Chrupalla, it has 83 MPs;

- Left Party (Die Linke), a left-wing populist party, was formed in June 2007 from the merger of the PDS, which had emerged from the SED, with the Alternative for Labour and Social Justice (WASG), a movement founded on 22 January 2005 and bringing together the former communist elite and those disillusioned with social democracy. Led by Jan van Aken and Ines Schwerdtner, it has 39 seats.

1 MP belongs to the South Schleswig Voters' Association, which represents the Danish minority.

The upper house, the Bundesrat, is made up of the members of the governments of the 16 Länder. Each Land has at least 3 votes; those with more than 2 million inhabitants have 4 votes; those with more than 6 million, 5 votes and, finally, those with more than 7 million, 6 votes. In total, the Bundesrat has 69 members.

Finally, Germany indirectly elects its President of the Republic (Bundespräsident) every 5 years. Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) was re-elected on 13 February 2022 by the Federal Assembly (Bundesversammlung), which comprised the 736 members of the Bundestag and an equal number of elected representatives from the country's 16 Länder, members of regional parliaments and leading figures from civil society.

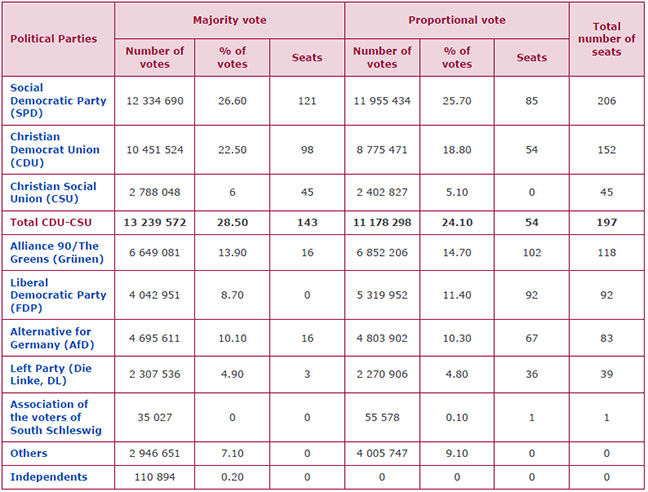

Results of the federal elections in Germany on 26 September 2021

Turnout: 76.5 %

Source : https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/bundestagswahlen/2021/ergebnisse/bund-99.html

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

15 April 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

25 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

18 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

14 January 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :