Analysis

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

-

Available versions :

EN

Corinne Deloy

On 9 June, Belgians will elect the 150 members of the House of Representatives, the 313 members who will sit in the Walloon, Brussels, Flemish and German-speaking Community parliaments, as well as the Kingdom's 22 elected members of the European Parliament. Belgium has not voted for 4 years, the longest period without a ballot in peacetime since 1830, as Jean Faniel, Director General of the Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques (CRISP), has pointed out.

The country has been governed since 30 September 2020 by the so-called Vivaldi coalition. Led by Alexander De Croo (Flemish Liberals and Democrats, Open VLD), it includes the Reform Movement (MR), the Flemish Christian Democrats (CD&V), the Socialist Party (PS), Vooruit (formerly the Flemish Socialist Party), Groen and Ecolo! This coalition of 7 parties is a first in the country. Its heterogeneity is significant, making agreements difficult.

According to an opinion poll carried out by the Kantar Institute for RTBF and the daily La Libre Belgique, the Vlaams Belang (VB) is expected to come out ahead in the general elections in Flanders with 26% of the vote, followed by the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) with 20.9% and the Workers’ Party (PTVB/PVDA) with 12.2%. The CD&V is expected to win 11.6%, Vooruit 11.5% and Open-VLD, the party of outgoing Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, 10.6%.

In Wallonia, the Socialist Party (PS) is forecast to attract a quarter of the electorate and win 25.4% of the vote, ahead of the MR, with 20.8%. The Workers' Party is projected to take 3rd place with 16%. It is due to be followed by Les Engagés (formerly the Humanist Democratic Centre), with 13.9%, and Ecolo, with 12.7%.

Finally, in Brussels, the MR is in the lead with 22.9% of the vote. Ecolo is in 2nd place with 15.5%, ahead of the PS (14.2%) and the Workers' Party (14%).

Outgoing Prime Minister Alexander De Croo is one of the country's most popular figures in all three regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels-Capital). However, his party is struggling to make any headway. The majority of voters in Flanders would like to see NVA leader Bart De Wever at Belgium’s helm, while Wallonia and Brussels prefer former Prime Minister (2019-2020) Sophie Wilmès (MR).

Pre-election polls show a rise in radical forces, both left and right, in Belgium. This protest vote is characteristic of the low level of confidence that citizens have in their political representatives. According to Benjamin Biard, a political scientist at CRISP, voters for Vlaams Belang and the Workers' Party are those with the least confidence in democracy.

The victory of parties on opposite sides of the political spectrum makes it difficult to form a federal government. The record is 541 days in 2010-2011. For Carl Devos, professor of political science at Ghent University, the next Belgian coalition government is bound to be formed by parties that are among the losers in the 9 June vote, given the large number of parties that were members of the outgoing government.

Socialist leader Paul Magnette could well see himself as the leader of a Vivaldi 2.0 coalition: "Paul Magnette is a candidate, his political family will be the biggest on election night, and so will his party within that family. He has experience, he knows his groundwork, he knows Flanders well, he speaks Dutch and he enjoys international popularity and influence (...) But his very left-wing approach, to counter the Workers' Party, is not going down well in a Flanders that will vote right-wing", said Carl Devos.

How far will the Workers’ Party go?

The match between the Socialist Party and the Workers' Party is central to the elections in Wallonia. The programme of the radical left party, whose spokesman is Raoul Hedebouw, focuses on tax justice (defending the taxation of wealth), the defence of purchasing power, the fight against "political privileges" and support for a socially just climate policy. It remains ambiguous about its support for NATO strategy and defends the idea that the West is responsible for the conflict between Ukraine and Russia.

According to opinion polls, the Workers' Party is attracting people who voted for both the Socialist Party and Ecolo in the previous general election on 26 May 2019.

The Socialists criticise the radical activists for proposing the most generous social measures, as long as they refuse to rub shoulders with those in power. "You have to vote for the parties that take their responsibilities", Paul Magnette repeats. Raoul Hedebouw nevertheless maintained that his party's position of principle was not to remain in opposition, and that it was ready to participate in a government in which it could apply its programme for a break with the past, i.e. introducing a retirement age of 65, freeing up salaries, taxing large fortunes and putting an end to the policy of austerity.

When asked about the reasons behind the Workers' Party's breakthrough in the kingdom's French-speaking community since the previous general elections on 26 May 2019, Emilie van Haute, professor of political science at the Free University of Brussels, explains: "The nature of the public debate is quite different: in Flanders, it is much more focused on migration issues, which is very favourable to Vlaams Belang, the party that has made these issues its main campaign theme. Conversely, on the French-speaking side, the public debate focuses on economic, social and environmental issues". Unlike the situation in Flanders for the radical right, there is no cordon sanitaire to prevent the radical left from taking office in Wallonia.

The MR, led by Georges-Louis Bouchez, who has been in every government since 1999, is the only right-wing force in Wallonia. Former Prime Minister (2019-2020) Sophie Wilmès is leading the fight against the radical left. "We have to be much less indulgent about the programme offered by the Workers' Party. It's a programme of rejection, finger-pointing and total irresponsibility. Their magic recipes don't work anywhere. These are recipes for impoverishment", she declared.

The party has recently become more right-wing, particularly in socio-cultural matters. This direction is criticised by some members.

Ecolo is losing ground in opinion polls because of speeches questioning its programme for defending an overly punitive ecology.

The CD&V advocates a model with four entities (Flanders, Wallonia, Brussels and the eastern cantons, which include the German-speaking community), which would be a sort of mini-entity due to its small size and population. The French community would disappear in favour of Wallonia and Brussels. The party wants to give the federated entities greater fiscal autonomy, and to transfer to them competences that are the responsibility of the federal level, such as health and labour market policy.

Vlaams Belang expected to come first in Flanders

In Flanders, the match is between the NVA and Vlaams Belang. The latter is leading in opinion polls, a first in Belgian history. Tom Van Grieken's party, whose slogan is "Eigen volk eerst" (Our people first), is riding high on an election campaign focused on immigration issues, a subject on which it is seen by Flemish voters as the party offering the best solutions. The main issue put forward by NVA voters is separatism and the introduction of confederalism. "Vlaams Belang is an anti-system party, and a vote for it is a way of kicking politics and centrist parties in the butt. It is a Flemish nationalist party for an independent Flanders. It has also adopted socio-economic positions that make it look like a left-wing party in this area, but the factor in Vlaams Belang's success is clearly its programme on immigration," said Vincent de Coorebyter, President of the Centre for Sociopolitical Research and Information (CRISP) and holder of the Chair of Contemporary Social and Political Philosophy at the Free University of Belgium (ULB).

"Vlaams Belang is the only party that has no part in the present government: we are seeing a rise in discontent among voters, a lot of negative emotion, and the party is managing to channel this anger and embody a solution to the mistrust of the political class in Flanders. Polls show that few voters feel represented by the political class in office, and Vlaams Belang plays on this feeling to a great extent," analyses Laura Jacobs, a political scientist at the University of Antwerp.

In May 1989, an agreement was signed by the 5 Flemish political parties of the time (the Social Christian Party, the Socialist Party, the Freedom and Progress Party, the People's Union and Agalev) in which they undertook to refuse any alliance with Vlaams Belang (called Vlaams Blok at the time).

A quarter of first-time voters say they are prepared to vote for Vlaams Belang (24%), according to an opinion poll conducted by PXL Ecole for TV Limbourg. Ecolo is the second party to attract the youngest voters (17.7%), followed by the NVA (15.80%). Vlaams Belang is the party with the strongest presence on social networks.

The NVA is being therefore outstripped by Vlaams Belang in opinion polls for the first time in Flanders. Nevertheless, if the polls are to be believed, Bart De Wever's conservative and liberal party is attracting many Open-VLD supporters.

Vlaams Belang leader Tom Van Grieken has declared himself in favour of a government alliance with the NVA in Flanders. Bart De Wever is not convinced by this proposal and has declared himself totally opposed to it. He knows full well that if he governs in coalition with Vlaams Belang in Flanders, he will be unable to find a majority at federal level. If he does refuse, his chances of becoming Prime Minister of Belgium remain the same, but he will then have to join forces with many other parties to form the government in Flanders and at federal level, which will make it very difficult to pass a reform of the State instituting more confederalism.

Bart De Wever repeats that he wants to do away with the Vivaldi coalition, which he believes is ruining Flanders, and that he wants to be able to set the agenda himself. Nevertheless, Flanders remains the most important thing for him. "In any case, he doesn't really want to do that; above all, he wants to remain mayor of Antwerp", says Carl Devos, professor of political science at Ghent University.

The NVA has chosen to present lists in the 5 Walloon constituencies for the general elections.

The Workers' Party (PVDA in Flanders), which is the only unitary party in the country, is credited with 12.2% of the vote in Flanders and could thus become the third party in the region behind the 2 radical right-wing parties.

The Belgian Political System

In 1830, the Kingdom of Belgium was founded from the merger of the former Austrian Netherlands and the Principality of Liège. At the time, while the majority of the population spoke Dutch, the nobility and bourgeoisie spoke French. The majority of Dutch-speakers were Protestants (Calvinists), while the French-speakers were Catholics. French-speaking dominance of the country as a whole lasted more than a century before, in the 1960s, Wallonia began to decline whilst Flanders' economy started to boom. The Walloons demanded greater autonomy to combat their region's industrial decline. The tensions that arose between the two communities led to several constitutional reforms (1970, 1980, 1988-1989, 1993, 2001 and 2011) which, over the years, have transformed Belgium into a federal state.

The kingdom has 3 regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels-Capital), 3 linguistic communities (French-speaking, Dutch-speaking and German-speaking) and 2 community committees. In 1993, Article 1 of the Constitution stated that Belgium would cease to be a unitary state. New federal powers were transferred to the regions, which were already responsible for education, culture, social policy, housing, the environment, regional planning and, with a few exceptions, employment and the economy (foreign trade, agriculture). The regional parliaments became institutions elected by direct universal suffrage. The 2001 reform gave the regions fiscal autonomy. 70% of the federal state budget is redistributed to them. As a result of these developments, Belgium no longer has any national political parties, a break that has reinforced linguistic and institutional differences.

The political scene is composed of French-speaking parties in Wallonia and Dutch-speaking parties in Flanders, which coexist only in the Brussels-Capital Region. Flemish and Walloons each have their own media, and the only things they have in common are the royal family, the flag, the judiciary and the army.

The sixth reform of the State, adopted in 2014, transferred entire areas of competence and financial resources to the regions (employment) and communities (family allowances), entities to which it offers an unprecedented degree of autonomy. As a result, the Flemish government manages a larger budget than the federal state (excluding public debt).

The Belgian political system was founded on pillarisation. Political parties have developed on the basis of cleavages within society: firstly, a religious (Church/State), then a regional cleavage (Walloons/Flemish) and, finally, a social divide (labour/capital). The political parties that grew out of these divisions were for a long-time veritable entities within the kingdom, each managing a multitude of organisations (schools, insurance companies, etc.), taking care of party members and their families virtually from birth to death. In exchange for their political loyalty, the members of these various organisations were given jobs, housing and other social benefits. For their part, the leaders of the various political parties shared out the posts to be filled in the public administration on an equitable basis.

This system worked perfectly for decades before it broke down at the end of the 1970s. Over the following decade, several new political forces appeared on the political scene: the ecologists, then the far-right nationalists (the Popular Union, the Vlaams Blok which became the Vlaams Belang, the NVA, the Front démocratique des francophones bruxellois, the Rassemblement wallon and the Front national). These new parties enjoyed growing success. The Socialists and Christian Democrats, who for decades accounted for the vast majority of the Belgian electorate (73.40% of the vote in the general elections of 18 May 2003), represented less than half of the electorate (44.98%) in the last general elections on 26 May 2019.

The Belgian Parliament is bicameral. The House of Representatives has 150 deputies and the Senate has 60 members, 50 of whom are appointed by the regional parliaments (29 Dutch-speaking, 20 French-speaking and 1 German-speaking) and 10 co-opted (6 Dutch-speaking and 4 French-speaking).

Voting is by full proportional representation with the highest average (d'Hondt method) in 11 electoral districts, the 10 provinces (5 in Flanders and 5 in Wallonia) and Brussels. Each of these elects between 4 (Luxembourg) and 24 (Antwerp) deputies. Brussels voters elect 15 deputies, either Dutch-speaking or French-speaking.

Belgians can vote for all the members of a list, for one or more actual candidates, for one or more substitute candidates, or for both actual candidates and substitutes. In order to stand for election, depending on the size of the electoral district, "small" parties must collect between 200 (Walloon Brabant or Luxembourg) and 500 signatures (other French-speaking provinces and Brussels) for the House of Representatives, while the signatures of 3 MPs are sufficient for "large" parties.

Each party must obtain a minimum of 5% of the votes in a constituency to be represented in parliament. Candidates for parliament must be at least 21 years old, and the lists presented to the electorate must have equal representation.

Voting is compulsory in Belgium. In fact, Belgium was the first country in the world to introduce compulsory voting in 1896 (for men only at the time). Abstainers can be reprimanded (if they abstain for the first time) or fined between €40 and €80. This can rise to almost €200 if the offence is repeated. However, it is rare to be prosecuted for not voting.

According to an opinion poll published last March, one Belgian in three would stay at home if voting were not compulsory, which is in line with the average abstention rate in many European countries. Urban dwellers and Walloons are the least likely to participate.

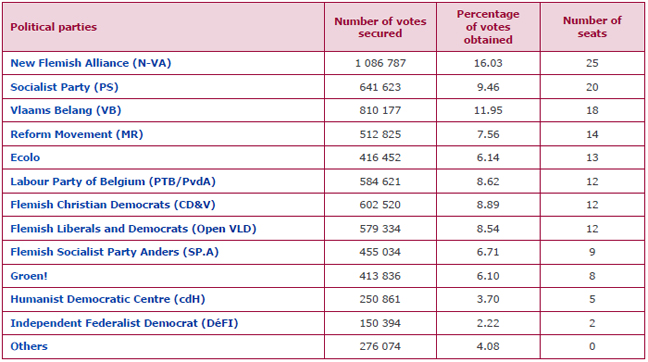

12 political parties are represented in the current House of Representatives:

- the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), a Flemish nationalist party formed after the dissolution of the Flemish regionalist People's Union party on 19 September 2001 and led by Bart De Wever, has 25 MPs ;

- the Socialist Party (PS), led by Paul Magnette, has 20 seats;

- Vlaams Belang (VB), a far-right party led by Tom Van Grieken, has 18 MPs;

- the Mouvement réformateur (MR), a liberal party led by Georges-Louis Bouchez, has 14 seats;

- Ecolo, a French-speaking green party co-led by Rajae Maouane and Jean-Marc Nollet, has 13 seats;

- the radical left-wing the Workers' Party of Belgium (PTB/PvdA), led by Raoul Hedebow, has 12 seats;

- the Flemish Christian Democrats (CD&V), led by Sammy Mahdi, have 12 MPs;

- the Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open VLD), the party of outgoing Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, led by Egbert Lâchait, has 12 seats;

- the Flemish Socialist Party (SP.A), which became Vooruit on 21 March 2021 and is led by Melissa Depraetere, has 9 seats;

- Groen !, Flanders' ecologist party led by Nadia Naji and Jeremie Vaneeckhout, has 8 seats;

- the Centre démocrate humaniste (CDH), which became Les Engagés on 12 March 2022, led by Maxime Prévot, has 5 MPs;

- the Fédéralistes démocrates francophones (FDF), which became DéFI-Démocrate fédéraliste indépendant and is led by François de Smet, has 2 seats.

Results of the 26 May 2019 general elections in Belgium

Turnout: 93.93 % (obligatory vote)

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

15 April 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

25 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

18 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

28 January 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :