Analysis

News

Corinne Deloy,

Rachel Ischoffen

-

Available versions :

EN

Corinne Deloy

Rachel Ischoffen

On 27th April Icelanders will vote to elect the 63 members of the Althing, their single parliamentary chamber. Less than a year ago they re-elected President of the Republic Olafur Ragnar Grimsson for the fourth time. The outgoing head of state collected 52.78% of the vote, ahead of Thora Arnorsdottir, with 33.16% of votes.

Iceland is run by a left-wing government that includes the Social-Democratic Alliance of outgoing Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir (Social-Democratic Party of Iceland, Sam) and the Left-Green Movement (Vg). A month before the Parliamentary elections, the right-wing opposition is the big favourite in the polls. Early voting began on 2nd March both for voters living in Iceland and those abroad.

Iceland on the road to economic recovery

Iceland was seriously affected by the 2007-2008 economic crisis and went bankrupt. Icelandic banks, which had attracted numerous foreign clients and committed no less than ten times the country's GDP found themselves with their backs to the wall, unable to continue to finance their operations or reimburse their creditors or their depositors. Devaluation of the Icelandic krona by half of its value led to the ruin of many companies, who found themselves unable to reimburse their debts, and household ruin: over the course of the previous five years their income had increased by an average of 45% and their debt levels - in foreign currency - had doubled. Corporate bankruptcies multiplied and the number of unemployed exploded. At the end of September 2008, the bankruptcy of Glitnir bank resulted in its nationalisation (which happened on 6th October) and that of the Kaupthing and Landsbanki banks. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) granted a €1.6 billion loan to Iceland and the government passed an emergency plan in November 2008 providing for restructuring of the banking sector, aid for the creation of businesses, the establishment of a reconstruction fund and the launch of a major works programme.

On 23rd April 2012, the former Prime Minister (1998-2009) Geir H. Haarde (Independence Party, Sja) was declared guilty of Iceland's bankruptcy in 2008 by a special court. He was not penalised, however. To date, only two people have been sentenced although several cases remain open. Special prosecutor Olafur Thor Hauksson has announced that he is going to bring proceedings against Heidar Mar Sigurdsson, former managing director of the country's largest bank Kaupthing, and against eight other former directors of the bank. Heidar Mar Sigurdsson is accused of having bought Kaupthing shares using a loan from the bank before having them bought by his own holding company for the amount of 572 million krona (€3.6 million). This inflation of the shares earned him 325 million krona. A case will also be brought against 8 former directors and executive staff of Iceland's second bank, Landsbanki, including its former managing director Sigurjon Arnason, for having maintained the price of their bank's shares at artificially high rates.

The Icelandic bank Landsbanki had created an on-line bank, Icesave which, using high interest rates, promised its depositors a high return and had managed to attract cash from numerous British and Dutch investors (around 320 000 people).

When the system crashed, and after the banks were nationalized, Iceland found itself owing a heavy debt (€3.8 billion) to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. An agreement on reimbursement, signed between Reykjavik, London and The Hague, was ratified by the Althing on 31st December 2009. But on 2nd January 2010, the President of the Republic Olafur Ragnar Grimsson announced that he refused to sign the law. A referendum was organized on 6th March 2010 by which the Icelanders confirmed the decision of their Head of State, by 93% of the vote, and rejected the agreement. On 16th February 2011, Parliament passed a new law on the Icesave agreement. On 20th February Olafur Ragnar Grimsson decided to organize another referendum and on 9th April 2011 the Icelanders again said "No" (by 58.90%) to the Icesave agreement.

On 28th January 2013, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Court, acquitted Iceland of all charges concerning the possible violation of the agreement signed within the context of its dispute with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands regarding bankruptcy of the on-line bank Icesave. The Court said that although bank customers must be protected, a State cannot be required to intervene in this protection. If the banks' assets are insufficient, it is up to the bankers to take action. A few days after this decision was announced, on 14th February this year, the Fitch ratings agency increased Reykjavik's sovereign rate by one point (BBB) and spoke of an "impressive recovery" with regard to the Country's economic development.

The country can now show satisfactory economic indicators. The GDP growth rate increased to 2.6% in 2012 and should be at 2.3% this year, according to the IMF. The country's debt has fallen. Public debt represents 100% of GDP, but should be brought down to 80% by 2016. The unemployment rate is down, at 4.7% of the active population in February 2013 (7.3% in December 2011). The inflation rate is now below the 4% mark and should continue to fall. Spending power is now also close to that in 2008. "We have not chosen the orthodox way. We allowed the banks to go bankrupt, established capital control and did not use the austerity cure as has been the case in other European countries. In our economic plans we ensured the preservation of the Welfare State, particularly in terms of education and health. Iceland's rapid recovery is due to strong devaluation of its krona, which stimulated exports" declared Icelandic President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson.

However, the Icelandic economy is still dependent on two activities (fishing, which represents 10% of the island's GDP and 40% of its exports) which are highly exposed to the economic climate and to variations in world prices. Also, according to the agreement signed in 2011, Iceland has to lift its exchange controls in 2013. Many analysts believe that the sudden lifting of restrictions could result in a major fall in the value of the Icelandic krona, endangering the country's recovery.

The left in power: 2009-2013

Iceland's bankruptcy brought its people into the streets in October 2008. In January 2009 these demonstrations turned into riots in a country that had known only one single violent demonstration in all its history, in 1949 when the country joined NATO. The pots and pans revolution (so called due to the noise made by demonstrators who banged pots and pans to get their voices heard) caused in the end the fall of Geir H. Haarde's government.

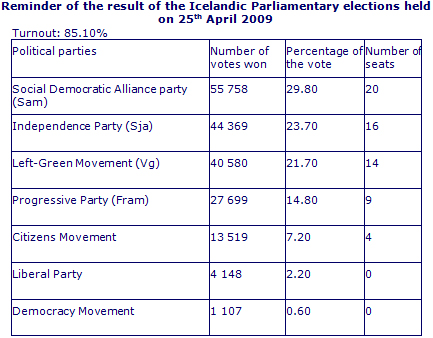

On 25th April 2009, the left-wing won an historic victory, winning an absolute majority in the early parliamentary elections, a first since the country's independence in 1944. The leader of the Social-Democratic alliance, Johanna Sigurdardottir, in office since 1st February 2009, was confirmed in his position as Prime Minister and formed a government with Steingrimur Sigfusson's Left-Green Movement.

Source: Website mbl.is

Source: Website mbl.is

The politico-economic crisis, and more specifically the collapse of the financial system and the political class's inability to prevent the crisis, to manage the banks' bankruptcy and to deal with the social unrest of 2008-2009, led to a plan to reform the Icelandic Constitution. The fundamental law dates back to 1944.

On 27th November 2010, 39.95% of Icelanders took part in the election of an assembly of 25 people responsible for contributing to the drafting of amendments to the Constitution. There were 522 candidates in this election. The Supreme Court cancelled the election in January 2011 after the Independence Party, which was opposed to the process, voiced doubts about the fairness of its organisation. The government finally chose to transform the assembly into an ad hoc commission of the Althing and on 24th March 2011 a council comprising the 25 people elected the previous November (mainly university professors, doctors, company managers and journalists) was asked to complete the work. The council's recommendations were submitted to Parliament on 29th July 2011.

On 20th October 2012, half the voting population (49%) took part in a referendum on the new Constitution. 66.30% said "Yes" to the following question: Do you want the 114 proposals presented to act as the basis for a new Constitution? The Venice Commission, a body of the Council of Europe specializing in constitutional law, to which the text was then submitted, noted obscurities in the text and warned the Icelandic authorities against rushing into adoption of the measures proposed.

The text now has to be approved by the majority of MPs in two different legislatures in order to be adopted.

A changing political landscape

Left-wing forces have always been divided in Iceland, whereas the right-wing has shown voters a united front. The Independence Party was predominant for many years. It won the Parliamentary elections of 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003 and 2007 before falling in 2009. A liberal party, it is divided on the question of Icelandic membership of the European Union. Within the party, pro-Europeans have formed a group known as the Independent Europeans.

The Progressive Party (Fram), led by Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson and favourable to a European Iceland, was a partner of the government between 1995 and 2007.

Outgoing Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir's Social-Democratic Alliance party is the leading left-wing party. It has been led since 26th February 2013 by Arni Pall Arnason, former Minister of Social Affairs (2009-2010) and Trade (2010-2011). The Social-Democratic Alliance Party, which has just changed its name to the Alliance Social-Democratic Party, is pro-European.

Further left, the Left-Green Movement (VG) has just changed its leader. The Education, Culture and Science Minister, Katrin Jakobsdottir has been elected to lead the party with 98.4% of the vote, replacing Industry and Innovation Minister, Steingrimur Sigfusson.

Several parties have been created over the past few months, Guthmundur Steingrimsson (former member of the Progressive Party) and Heitha Kristin Helgadottir, (campaign manager for Jon Gnarr (Mayor of Reykjavik) in the last city council elections held on 14th October 2010) have, with others such as Robert Marshall (former member of the Social-Democratic Alliance Party) and Jon Gnarr, founded the Bright Future Party. Led by Guthmundur Steingrimsson and Robert Marshall, it is in favour of simplifying the taxation system, the creation of clean industries and Icelandic membership of the European Union.

Dawn - The Organisation for Justice, Fairness and Democracy was founded on 18th March 2012 from the merger of three parties, Birgitta Jonsdottir's Movement, Fridrik Thor Gutdmundsson's Citizens Movement and Sigurjon Thordarson's Liberal Party. This party, which is run by a council of 7, is fighting for the establishment of a new Constitution, stronger support for housing, limitation of the exploitation of natural resources and the nationalisation of energy providers, transparency of political, administrative and financial matters and the continued search for those responsible for the economic crisis. The party is in favour of continuing Iceland's negotiations with the European Union and the organization of a referendum to rule on the island's future.

The economist Lilja Mosesdottir, from the Left-Green Movement has founded the Samstatha (Solidarity) party. Certain that the Icelandic krona will be massively devalued when exchange controls are lifted (planned for 2013), she wants to set up a new currency (Nykrona, the new krona).

Thorvaldur Gylfason, economics professor and a member of the commission that drafted the proposals for the new Constitution founded the Democracy Watch Party on 16th January 2013. The party focusses on economic questions, notably private debt (households and businesses) and public debt. In favour of adopting a new Constitution, he refuses to make any pronouncement regarding Icelandic membership of the European Union.

Finally, Iceland also has a Pirate Party, led by Birgitta Jonsdottir (former member of the Citizens Movements), which defends civil rights, direct democracy, freedom and the transparency of information.

The Icelandic political system

Iceland is home to the world's oldest parliament. The Althing was founded in 930, at the time grouping together a legislative assembly and a court. At the end of the 12th century, it had become nothing more than a simple court of justice, which was done away with in 1800 and then re-established to its functions of consultative assembly in 1843 by the King of Denmark. A single-chamber Parliament since the disappearance of the Upper Chamber in 1991, the Althing has 63 members elected by proportional representation (according to the Hondt method) for a period of no more than 4 years.

For the Parliamentary elections, Iceland is divided into 6 circumscriptions. Each one elects a number of MPs in proportion to its population (between 7 and 11). The remaining 9 seats, known as equalization seats, are allocated according to a method that takes account of the parties' results at national level and of how voting is distributed within the circumscriptions. Each individual political party has to collect at least 5% of the votes cast in order to be represented.

Political parties have to collect at least 300 signatures from voters in order to stand for the parliamentary elections. They have until 12th April 2013 to submit their lists.

The parties represented in the Althing are:

– The Social-Democratic Alliance Party of Iceland (Sam), born in January 1999 from the merger of the Social-Democratic Party, the People's Alliance and the Women's Party. Led since 26th February 2013 by Arni Pall Arnason, it has 19 seats.

– The Independence Party (Sja), founded in 1929 and led since 29th March 2009 by Bjarni Benediktsson; it has 16 MPs.

– The Left-Green Movement (Vg), led by the Education, Culture and Science Minister, Katrin Jakobsdottir, with 11 seats.

– The Progressive Party (Fram), agrarian centrist party, led by Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, with 9 MPs.

– the Movement of citizens with 1 seat

8 MPs have changed party and 6 have founded their own party during the course of the legislature. Thus, Atli Gislason and Jon Bjarnason, former member of the Left-Green Movement left their party and are now registered as independent MPs.

Reykjavik on the road to EU membership?

On 16th July 2009, Iceland became an official candidate for EU membership. On 17th June 2010, the European Council opened membership negotiations with Reykjavik, 27 chapters (from a total of 33) are open and 11 have already been closed, including those on freedom of movement of workers, industrial policy, justice and fundamental rights, foreign policy, security and defence, competition policy, education and culture.

Chapters 13 and 11, on agriculture and fishing, are the most delicate and are to be addressed after the parliamentary elections. The question of fishing quotas, particularly mackerel fishing, is a stumbling block between Iceland and the European Union. Moreover, whaling is banned by the EU but authorized by Iceland.

On 14th January 2013, Reykjavik decided on a break in its negotiations with the European Union, to last until after the elections on 27th April.

The coalition in power is divided on EU membership. The Social-Democratic Alliance Party of Iceland is favourable to membership, whereas the Left-Green Movement is opposed to it. The social-democrats highlight the fact that if Iceland became a member of the EU, this would be an advantage for both consumers and businesses. In their opinion, the euro would give the country monetary stability. The single currency would act as a rampart against drifting of the financial system and would mean that foreign investment could be attracted. Finally, Iceland could benefit from structural funds in order to develop both its agriculture and its tourist industry. As far as opponents to the European Union are concerned, Iceland would lose its independence and sovereignty if it became a member of the EU; it would lose control of its n°1 resource, i.e. fishing, and its agriculture would be devastated. Farmers and fishermen alike are, moreover, strongly opposed to their country joining the Union. Anti-Europeans also highlight the fact that, after joining, Reykjavik would no longer be in a position to control its own economic policy and could no longer defend its own interests; they anticipate an increase in corporate tax, condemn the burden that would be put on businesses by European regulations and, finally, claim that Iceland, which is a small State (319 000 population in 2011), would be powerless within the Union. The President of the Republic, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, is opposed to his country joining the European Union.

A member of the European Economic Area (EEA) since 1994, Reykjavik benefits from access to the European internal market. The country has also joined the Schengen area.

Euroscepticism is growing and is in the majority in Iceland. In the public opinion survey carried out by the Capacent Institute in October 2012, 57.6% of people questioned declared themselves opposed to membership. Icelanders, on the road to economic recovery, are asking themselves questions as they see the Union struggling with the debt crisis. The continuation of the island's European project will depend on the results of the parliamentary elections. The Independence Party and the Progressive Party, favourites in the polls, want to hold a referendum on the European question, before considering any kind of return to membership negotiations.

According to the latest opinion poll carried out by the Market and Media Research Institute (MMR) and published on 27th March, the Progressive Party is in the lead, with 29.5% of the vote. It would come out ahead of the Independence Party, which would collect 24.4% of the vote. On the left, the Social-Democratic Alliance Party of Iceland would receive 12.5% of the vote and the Left-Green Movement, 8.7%. The Bright Future Party would win 12% of the vote, and the Pirate Party 3.9%.

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

15 April 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

25 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

18 February 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

28 January 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :