News

Corinne Deloy,

Fondation Robert Schuman,

Helen Levy

-

Available versions :

EN

Corinne Deloy

Fondation Robert Schuman

Helen Levy

Researcher at the Robert Schuman Foundation

On 31st October last Prime Minister George Papandreou (Panhellenic Socialist Movement, PASOK) announced the organisation of a referendum on the rescue plan for Greece approved by the European Union on 27th October in Brussels. The latter aimed to help Greece pay off its debts but obliged the country to submit to economic supervision and to implement a stricter austerity regime. The announcement was the source of stupor and indignation in Greece and across all of Europe – it sent the European, American and Asian stock exchanges into disarray and surprised the financial markets.

"It's suicide", declared Michalis Matsourakis, chief economist at the Greek Alpha Bank, who perceived an attempt on the part of George Papandreou to break out of his solitude and the political crisis that was undermining the country as he pushed the opposition parties, which until now had categorically refused to support the strict austerity measures taken by the government, to adopt a position on the European plan, in order to calm the social protest movement that went together with a sharp decline in living standards. The Prime Minister, who was finding it increasingly difficult to find support within his own socialist party and the ministers of his government, had already suggested to the opposition that they create an alliance in the shape of a government coalition in June 2011. The right however, rejected this proposal.

In the announcement made by George Papandreou the European authorities perceived a gamble, which threatened the rescue plan over which Athens European partners had found it difficult to come to agreement. "George Papandreou calculated badly as far as the international reaction was concerned, which shows he was panicking," declared political analyst Georges Sefertzis.

On 9th November 2011 Georges Papandreou was finally forced to resign. He was replaced two days later by Lukas Papademos, former Vice-President of the European Central Bank and former Chairman of the Greek Central Bank, who formed a national unity government after an agreement was reached between the three political parties: the PASOK, New Democracy (ND), and the far right People's Orthodox Alarm (LAOS). The new Prime Minister is an acknowledged expert, which reassured Greece's creditors and partners in the euro zone and a true connoisseur of the European institutions. It was his task to save the country from bankruptcy and to avoid its exit from the euro; he called on the "unity and cooperation of all of the parties" in order to complete his work. Two Deputy Chairmen of New Democracy, former European Commissioner for the Environment (2004-2010) Stavros Dimas and former Mayor of Athens, Dimitris Avramopoulos, made their debut in government. The party then held six posts in the new team. LAOS had four ministers, an all time first in the country's history. Outgoing Finance Minister Evangelos Venizelos (PASOK) retained his post.

"I am taking over at the most difficult time in our country's modern history. Everything is still uncertain," stressed Lukas Papademos as he spoke to the Vouli (parliament) on 14th November. The new prime minister, who gave up his salary, won the majority of 255 votes in parliament. 38 MPs voted against the new government and seven abstained. The Communist Party (KKE) and the Radical Left Coalition (SYRIZA) qualified Lukas Papademos's government as anti-constitutional and illegitimate, and demanded the organisation of early general elections.

The government led by Lukas Papademos was to complete the operation that comprised wiping out part of the country's debt and to ensure the introduction of a second rescue plan put forward by the euro zone. "His mandate is to finish by 12th April" (when the exchange of agreement bonds on the restructuring of the Greek debt will be completed), the government's spokesperson, Pantelis Kapsis announced. The Prime Minister always said that he did not want to serve the two remaining years of his mandate. "The goals set for the next five months (i.e. the exchange of a part of the debt with private creditors that is supposed to wipe out 100 billion € of the country's debt and to prevent bankruptcy) have been achieved," declared the New Democracy leader, Antonis Samaras.

On 11th April last Prime Minister Lukas Papademos announced that the next general elections would take place on 6th May. Greece's European partners fear that this election will be to the advantage of the extremist parties (both right and left) or radical groups who are against the rescue plan and would have preferred the elections to be postponed. A recent poll shows that "the punishment" of those responsible for the crisis is the main motivation of a majority of Greeks (41.9%) in going to ballot on 6th May next. Slightly more than one quarter (29.5%) say they will give their vote to a party which seems the most competent to bring the country out of the crisis and 21.7% say they will vote for a party that is able to form a stable government and to undertake the necessary reforms.

An economic crisis of historic size

Just a few weeks after the victory of the PASOK in the previous elections on 4th October 2009 - with the slogan "There is money!"(Lefta uparxoun!)- the new Prime Minister George Papandreou revealed that Greece's deficit totalled 12.7% of the GDP - instead of the 6% announced by the previous government led by Costas Caramanlis (ND). The falsification of public accounts by the previous governments was brought to light and threw doubt over Greece's transparency with regard to its European partners. Market confidence was shaken and the ratings agencies downgraded Greece, which led to an increase in the interest rates at which Athens could borrow money. George Papandreou then presented his first austerity plan designed to reduce the country's deficit below the 3% GDP mark. At the beginning of 2010 the European Commission placed Greece under surveillance and the European heads of State and government guaranteed Athens their support. In April 2010 the country did however find itself unable to pay its bills and unable to honour its debts. George Papandreou was officially forced to ask Brussels for help.

In May 2010 Greece received 110 billion € from the IMF and the EU (a loan over three years). In exchange the government had to implement major austerity measures that were designed to save 30 billion € in 2012 (notably thanks to the privatisation of several state companies, the final goal being set at 50 billion € by 2015). Civil servants' salaries fell by 25% and retirement pensions by 10%; taxes increased (VAT rose to 23%). The number of obligatory semesters to be worked in order to be entitled to a retirement pension increased and many bonuses were abolished. Finally 30,000 civil servants were dismissed (the goal being to drop down a total of 100,000 within three years) and the government decided to stop replacing nine newly retired civil servants in ten).

However this plan did not enable the Greek economy to recover growth and it did not succeed in dissipating fears regarding its public finances. In 2011 the budgetary deficit was higher than planned, growth weaker than expected and many of the planned structural reforms had still not been implemented. On 26th and 27th October the European Council decided to draw up a second aid plan of 130 billion € in Athens' support.

The second plan was set in place in February 2012 in an emergency, since Greece absolutely had to reimburse 14.4 billion € in treasury bonds that had come to maturity before 20th March, otherwise it would have found itself unable to continue payments. This wipes out a part of the private debt by reducing the nominal value of the Greek State bonds by 53.5% (held by banks and investment funds) to a total of 107 billion €, i.e. half of the 206 billion € in loans subscribed to by the banks, insurance companies and other financial funds (Greece's total public debt lies at over 350 billion €, an amount that was reviewed upwards and which is an all time record). This has also been the biggest restructuring operation in history). Greek Finance Minister Evangelos Venizelos thanked the private creditors "for having shared the sacrifices made by the Greek people in this historic effort."

In exchange for their loss the international and Greek banks won a 30 billion € guarantee on the new bonds that will be issued. The financial rescue plan also went hand in hand with a new series of austerity measures: a 22% reduction in the minimum salary (586€ over 14 months), a 10% reduction in complementary pensions (the deficit of the pension funds is beyond 4.5 billion €). Athens has promised to save 3.3 billion €. Interest rates on loans granted to Greece have fallen and the added-value on Greek debts will be paid to Athens so that the country's funding requirements will be reduced (1.8 billion € in all). Several structural reforms have to be implemented including that of the civil service whose employees must be reduced significantly; likewise tax collection to counter tax evasion (flushing out those who do not pay the abolition of a number of tax rebates and the creation of new taxes). The government also has to make further cuts in public spending. Public utility tariffs have been increased (+50% on electricity for example) and privatisations must continue at a faster pace. "In 2012 private investments will rise to at least 9 billion €," declared Lukas Papademos.

According to financial analysts if Greece implements the planned reforms to reduce its living costs, it should achieve a primary surplus of 1.1% in 2012 – which will be a first in years (i.e. apart from servicing the debt). The goal is however an ambitious one given the present economic situation (GDP declining by 5.5% in 2011 and by 2.8% forecast in 2012). The government published its goals in terms of the public deficit: -6.1% in 2013, - 5.1% in 2014 and – 4.2% in 2015. Then the public debt should have dropped to 286 billion € i.e. 126% of the GDP. "The Greek economy has a difficult year ahead, from an economic, social and even a political point of view. It faces ten years of enormous sacrifice," indicated Savvas Robolis, professor of economics at the Panteion University of Athens.

The idea behind providing aid to Athens is to bring the country's debt level – which represents 160% of the GDP at present – down to 120.5% in 2020, i.e. a level deemed sustainable long term, so that the country can make a return on the markets mid-term. The 2012 budget that includes further tax increases, a reduction in civil servants' salaries and a reduction in the number of civil servants was approved 258 votes in support, 41 against.

"In order for the EU and the IMF to support Greece they must be certain that efforts will be maintained long term, that this does not just apply to the immediate future, but to this government also future governments," declared the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, adding "It is not a sprint but a marathon. This is why it is important to have absolute trust – because in the end it is a question of trust." "Our position in Europe is non-negotiable. Greece is and will remain part of a united Europe and part of the euro zone," indicated Prime Minister Lukas Papademos, who said that he was aware that this "participation involved obligations." Most Greeks (around 80% according to the most recent polls) support their country's membership of the euro zone. According to a poll undertaken mid February 82% of those interviewed placed the blame for the economic crisis on their government. Only 9.3% of them accused the markets and speculators and 6% blamed the IMF and the EU. "90% of the crisis is a political problem," declared Panagiotis Korliras, Chairman of the Centre for Economic Planning and Research (Kepe).

Since 2008 the country has been experiencing an economic recession. All Greeks are facing a downturn in their living standards at present. Every citizen knows someone in their immediate circle (either family or friends) who has lost their job; 150,000 jobs have been destroyed in the civil service over the last three years; many shopkeepers have had to close and are not entitled to any unemployment benefits. This, the most recent problem, affected 21% of the working population in December 2011 (10.2% in December 2009). Half of young people under 24 are unemployed, which is equivalent to an increase of 41.2% in one year according to figures released by the Greek Statistics' Authority (ESA). Between 2000 and 2010, whilst productivity stagnated, salaries rose in Greece by 54% (28.7% in Portugal and 18.6% in Germany). The black economy represents around one third of the official economy and the cost of tax evasion is estimated at 13 billion € per year. The Greek economy is due to contract by 4.5% in 2012 and the country's deficit is due to total 10.6% of the GDP.

"The government that takes office after the next general elections will have to continue the policy to consolidate public finance and reduce spending by 12 billion € in 2013 and 2014", warned Lukas Papademos adding, "the aim is to limit wastage and not to reduce salaries even more. This year and the beginning of next year will not be easy but we have to continue working so that the sacrifices made by the Greek people are not in vain."

The reasons behind the disaster

"The cause of the Greek debt lies in the confusion on the part of the country's leaders between the idea of credit and that of income," indicates Nicolas Bloudanis, a historian who adds "belonging to the single currency enabled Greece to borrow at low rates and therefore the political class strengthened its electoral base by recruiting increasing numbers of civil servants."

Since the return of democracy in 1974 both of the biggest parties, which dominate political life and have succeeded each other – the PASOK and New Democracy (ND) and have indeed consolidated the patronage system, which has been the trademark of the Greek State since the 19th century, thanks to the employment a great number of civil servants.

The Greek economy is controlled by the State and because of this it is not very operational. The public sector is atrophied (the State employs 45% of the working population) and the private sector comprises very small companies or really big maritime armament companies. The Greek economy's catastrophic situation can be explained in part by the profligacy of spending but also by the major structural weaknesses in the national economy.

The drying up of public funding and also European funds, that had been generously given to Athens since its entry to the EU in 1981 (but which the country did not use to develop its productive system and to improve the productivity of its industries), has placed the economy in great difficulty. Moreover the country's accession to the euro zone, which enabled Athens to borrow on the markets under the same conditions as Germany, only added to the growing deficit. According to a writer, Nikos Dimou, "the problem is mainly cultural. For years people have seen the State swell and take on half of the country in its employ. They have become accustomed to receiving money from the State and Europe. Tax evasion was not seen as a crime but a right." In Greece the State has always been seen as a distributor of money and privileges rather than as a regulatory body that can raise and redistribute taxes.

Greece's political, judicial and economic structures cannot be compared with those of other European countries. They have discouraged entrepreneurship and foreign investment and have demonstrated their ineffectiveness in the face of corruption. The country has always fostered tax exemptions rather than granting services funded by taxes. This policy has led to corruption (several financial scandals have come to light over the last few months) and impunity which many political or administrative figures have benefited from, which in turn has led to strong feeling by the Greeks with regard to the political and judicial institutions. "In Greece the State is an authoritarian State, of which we have to be wary," says Nicolas Bloudanis. "Given the State's inability to rise to the challenges the country faced, in the 19th century the Greeks invented "Evergitism", a tool to smooth out social inequalities," stresses Anastassios Anastassiadis. Evergitism is the name given to a social policy undertaken via private means.

The issues at stake in the general elections

The Greek political class has now mainly been discredited. Over the last few months many politicians, including the President of the Republic, Carolos Papoulias, have been booed by the population and suffered showers of projectiles during public events. The general elections on May 6th may fragment the political playing field. The two main parties - PASOK and ND – are running at their lowest ebb in terms of popularity since 1974, the year when the country returned to democracy (around 35% each). According to a survey by the pollster GPO undertaken at the beginning of April, the percentage of citizens who believe they are not represented by the existing political parties lies at 25%; 50.4% of the Greeks believe that neither of the leaders of the two main parties, Antonis Samaras and Evangelos Venizelos – is qualified to become the next Prime Minister.

Ahead in the polls, New Democracy (ND) hopes to take advantage of the Greeks' discontent after two years of strict austerity. Antonis Samaras is asking the electorate to give him an absolute majority "so that he has the necessary strength to negotiate abroad." Many analysts believe that a national unity government (an ND-PASOK coalition) would be beneficial to Greece but Antonis Samaras is having none of this. The two main Greek parties have had a difficult relationship for decades. "I want to have a free hand. A clear majority is necessary in order to govern the country properly," declared the ND leader who wants to reassure his European partners and repeats that he will scrupulously respect his country's commitments, ie the framework and goals of the second aid programme. He does however hope to be able to renegotiate the conditions of its completion after the elections. Antonis Samaras wants to establish his party on the right, demonstrating extremely firm positions over immigration and security in order to reduce potential voter defection over to LAOS, notably by those who accuse ND of having approved the transfer of national sovereignty. This far right party put forward the name of Lukas Papademos in 2009 to lead the government and to bring Greece out of the crisis. He earned his stripes as a responsible political partner by approving the international rescue plan of May 2010 with the PASOK. However the party voted against the second plan in October 2011.

Two new parties have recently been formed on the right. The Democratic Alliance (DS) was founded by former Foreign Minister (2006-2009) and the former Mayor of Athens (2003-2006), Dora Bakoyannis. The Independent Greeks Party (AE) was created on 24th February by former Maritime and Islands Minister Panos Kammenos. Both of these leaders are former ND members. Dora Bakoyannis was banned from it on 6th May 2010 after having voted in support of the first rescue plan (Antonis Samaras party was against it) and Panos Kammenos left it after having refused to provide his vote of confidence to Lukas Papademos.

"I took some difficult decisions. They might have cost me politically but they were worth it," declares George Papandreou. His successor at the head of PASOK, Evangelos Venizelos gave up his mandate as Finance Minister so that he could undertake his campaign. The PASOK is indeed at an all time low in the polls. When he was elected on 18th March Evangelos Venizelos (replaced by Filippos Sachinidis (PASOK)) admitted that PASOK owed the Greeks "honest apologies for our errors and our omissions." It is due to be the main loser in the election on 6th May, even though it will be required in the formation of the next government.

On the left two new parties have also been created: the Democratic Left, led by Fotis-Fanouris Kouvelis, which supports the agreement to reduce the Greek debt held by private creditors but is against the new austerity programme, which it wants to renegotiate, and the New Social Contract Party, led jointly by Luka Katseli, former Economy Minister (2009-2010), Employment and Social Security Minister (2010-2011) (excluded from PASOK after having refused to approve the reduction of the minimum salary), and Haris Kastanidis, former Justice, Transparency and Human Rights Minister (2009-2011), Interior (February-November 2011), which promises to lighten the present government's austerity plan.

On the far left the Radical Left Coalition (SYRIZA) is divided over the question of taking part in a national unity government. The party is asking for an increase in taxes on ship owners (Greece has the biggest merchant fleet in the world) and it wants the European Central Bank to have the right to print money. "It is a question of seeing whether there is an alternative in Europe, not just in Greece," stressed Alexis Tsipras, the leader of the SYRIZA group in Parliament and chair of one of its components, Synaspsimos. "Wealth is there but we cannot tax it; the Swiss banks are concealing 600 billion € held by Greeks, a sum that is higher than the country's debt," he added.

Finally the Secretary General of the Communist Party (KKE), Aleka Papriga declared: "We do not intend to work with SYRIZA because we have different goals. This party is a member of the system, we aren't." The Communists are against Greece's membership of the euro zone and the rescue plan.

The Greek Political System

The Vouli (Parliament) is unicameral and comprises 300 members, elected by proportional representation for 4 years in 56 constituencies. Voters can choose from a list and express their preferences. 51 constituencies appoint 288 MPs, the remaining 12, called national representatives since they represent all of Greece – an honorary position – are elected using the results of each of the political parties nationally. The electoral system of enhanced proportionality guarantees a 70% level of representation for the political parties who have the right to sit in Parliament (i.e. any political party winning at least 41% of the vote is guaranteed to hold the majority in the Vouli.

It is obligatory to vote in Greece up to the age of 70. Abstention can lead to a term in prison ranging from one month to one year.

5 political parties are represented in Parliament at present:

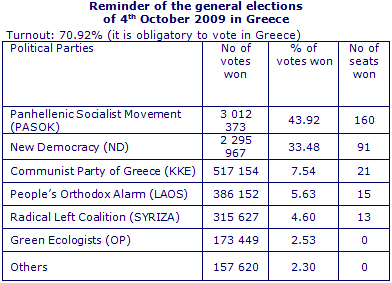

- The Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK), that won the general elections on 4th October 2009. Founded in September 1971 by former Prime Minister (1981-1989 and 1993-1996) Andreas Papandreou, the party has been led since 18th March last by former Defence Minister (2009-2011) and former Finance Minister (2011-2012) Evangelos Venizelos. It has 160 MPs[1];

– New Democracy (ND), centre-right, founded in October 1974 by former President of the Republic (1980-1995) and former Prime Minister (1955-1963 and 1974-1980), Constantin Caramanlis, is led by Antonis Samaras. It has 91 seats;

– The Communist Party (KKE), founded in 1918 that emerged from the Socialist and Workers Movement, is communist and anti-European; it is led by Aleka Papariga, with 21 seats;

– People's Orthodox Alarm (LAOS, which means people), a far right party founded in 2000 by journalist Georgios Karatzaferis, a former member of New Democracy, has 15 seats;

– the Radical Left Coalition (SYRIZA), a far left party founded in 2004 of the merger between Synaspismos and several leftwing groups (inlcuding the far leftwing of PASOK, communist sympathisers and ecologists). It is led by Alexis Tsipras, and has 13 seats.

The most recent polls reveal the explosion of the Greek political landscape that has been dominated since 1974 alternately by PASOK and ND. In the most recent survey by GPO for TV channel Mega on 11th April, Antonis Samaras's party, ND, is due to win 18.2% of the vote ahead of PASOK, 14.2% of the vote. The Communist Party is credited with 8%, the Independent Greeks Party, 7%, the Radical Left Coalition 6.2%, the Democratic Left, 5.9%, LAOS 4% and finally the neo-Nazi party Chryssi avghi (Golden Dawn) led by Nikolaos Michaloliakos, slightly more than 3%, which is vital if a party wants to be represented in parliament.

Neither of the two "main" parties will be able to form a government alone, the "small" parties will therefore find themselves in the position of kingmaker. "These general elections are difficult and vital for the future and are the start of a new period, the most important since 1974," stressed Thomas Gerakis, Director of the Marc research institute.

Source : Greek Interior Ministry

http://ekloges-prev.singularlogic.eu/v2009/pages/index.html?lang=en

Source : Greek Interior Ministry

http://ekloges-prev.singularlogic.eu/v2009/pages/index.html?lang=en

[1] the distribution of MPs given here is that of the general elections 4th October 2009. Since then it has changed; some MPs have been excluded from their party or have become independent. Today 55 MPs say they are dependent.

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Elections in Europe

Helen Levy

—

24 February 2026

Elections in Europe

Helen Levy

—

10 February 2026

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

20 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :