Strategy, Security and Defence

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

Poland has made security one of its top priorities during its Presidency of the Council (January-June 2025). Almost a year ago, the Commission presented a European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) aimed at strengthening European industrial capabilities. If implemented, this programme will bolster the European Defence Fund (EDF), launched in 2021 and which has already financed one hundred and sixty-two armaments industry programmes. Cooperation projects are numerous and extensive. The programmes selected by the Commission bring together an average of seventeen entities, and it takes care to appoint coordinating leaders in almost all the Member States. Questions are now beginning to emerge. After three years, it is useful to draw up a mid-term review to inform future choices.

***

The European Union faces crucial choices. Europe's security is the priority of the Polish Presidency of the Council, as it is for all the Member States, who are all united behind Ukraine. The first issue to be settled concerns capacity. In March 2024, the Commission presented a draft investment programme for the defence industry (EDIP) which is in line with the European programmes developed over the last few years. The European Defence Fund (EDF) planned for the period 2021/2027 is the main one.

A - The singular breakthrough of European support for the defence industry

1/ Until 2021, the European budget had no funds dedicated to defence

a) EU action in the field of defence is a matter for the Member States

Defence became part of the European Union's remit with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). The treaty was signed almost simultaneously with the break-up of Yugoslavia and a war on Europe's doorstep. It should have been "Europe's hour”[1], but the war in the Balkans was above all a demonstration of American supremacy. National armies took part in NATO operations, but the European Union was absent. Nevertheless, at the end of the conflict, following an agreement on cooperation with NATO[2], in 2003, the European Union succeeded in mounting its first military operation (EUFOR Concordia) in Macedonia.

The Lisbon Treaty of 2007 marked a step forward in organising the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)[3] and set out the missions that the European Union could undertake by drawing on the military capabilities of the Member States[4]. They can now establish in-depth cooperation: permanent structured cooperation (PESCO). The annexation of Crimea in 2014 provided a decisive impetus. The military threat had raised its ugly head again in Europe. This marked the beginning of a proliferation of politico-military initiatives by the Member States[5] and the Commission alike[6]. In practice, European defence policy has mainly been devoted to the deployment of military forces. However, this activism has hardly been reflected in the Union's budget. Military expenditure exists... but it is financed in other ways.

b) EU military operations are financed outside the European budget

Concordia, the European Union's first military operation, was followed by eighteen others, mainly in the Mediterranean and Africa[7]. Formally, these operations are joint actions decided on unanimously by the Council[8] and are a share of the common funding[9], but expenditure is financed by the Member States outside the EU budget[10]. The rules are set out in the Athena system[11]. Collective financing only concerns common costs. Coverage varies according to the nature of the expenditure and the phase of the operation. In 2021, the European Peace Facility (EPF), which succeeded Athena, became the main instrument for European military aid. Its remit has been extended to include assistance to strengthen the military capabilities of third countries by supplying both non-lethal and lethal equipment. Conceived as a military assistance tool for African countries facing terrorist threats, this mechanism has been used to finance military aid to Ukraine.

Prior to the European Defence Fund, the Facility was the most significant European development in the military field. Before Ukraine, most of these operations had been modest. In twenty years, the European Union's military operations have represented an expenditure of €628 million. On average, common costs account for only 10-15% of the cost of operations, which are still largely financed by individual states. On this basis, European military operations totalled between €5 billion and €6 billion.

In the case of military aid to Ukraine, financed by the Facility, the weapons are not supplied by the European Union, but are reimbursed to the States. The budget for the period 2021-2027 is €17 billion.

2/ The emergence of European support for the arms industry

a) The turning point in 2021

Firstly, the institutional lock was lifted. The Treaty text regarding military matters is simple: no progress without a unanimous decision by the Council[12]. The Union's involvement was upended by a procedural loophole. Although the defence industry is an area of national competence, it is first and foremost an industry that falls within the scope of internal market rules, areas in which the European Union has full legitimacy. Industry is a supporting competence[13] and the internal market has guided the Union's action since the Single Act of 1986[14]. All the funds created have been adopted by ordinary legislative acts. With this ‘gradual communitisation’, the Commission has become ‘a key player in defence matters’[15].

Secondly, the budget consolidated this spectacular breakthrough. Defence appeared for the first time in the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) under a new heading ‘security and defence’. Programming is not just a budget document setting expenditure ceilings, but also a political document establishing priorities. It therefore brings together support for the armaments industry and a mobility programme designed to improve military transport between states[16], even though this item only represents a modest share of the budget (1.23%). After the revision of the MFF on 29 February 2024, the figure totalled €16.4 billion (current prices). Military expenditure alone represents €11.14 billion over the period 2021-2027[17].

b) Armaments spending in the European budget

All security and defence-related initiatives focus on industrial capabilities and the armaments effort. Lack of investment and fragmentation of the supply of military equipment are the structural handicaps of the European defence industry[18].

The first initiative to promote European industrial cooperation was the creation in 1996 of the Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAr), an intergovernmental organisation that brings together a number of states, but which has no financial resources. In 2004, the Council created the European Defence Agency (EDA), designed to support cooperative defence industry projects between countries. The annual budget is limited, but the Agency's role is important enough for it to have been included in the Lisbon Treaty[19]. In 2018, the European Union created the European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP), a precursor to the funds that would follow.

The European Defence Fund (EDF) set up in 2021 has become the fund to support cooperative armaments projects. The war in Ukraine was a powerful catalyst. It led to the creation of an instrument designed to strengthen the European defence industry through joint procurement (EDIRPA) to support joint arms purchases involving at least three States[20]. The contribution paid by the Member States represents 15% of the total cost. The instrument has been allocated €300 million over the period 2023-2025. Then there is the ammunition production support programme (ASAP) which aims to increase the European industry's ammunition production capacity to 2 million shells a year by the end of 2025. The aid is paid to companies. The budget allocated is €500 million for the period 2023-2025.

Military spending in the European budget will total €1.8 billion in 2025. A derisory sum compared with the military expenditure of the Member States (€552 billion in 2024), but significant in terms of the European budget[21].

3/ The European Defence Fund, the main tool in the support of the armaments industry

a) A significant level of budgetary expenditure

Until 2021, the European Union's military spending was only symbolic. The only significant expenditure (linked to external interventions) was the responsibility of the Member States via specific funding outside the European budget. The European Defence Fund has introduced military spending into the European budget, initially with €8 billion over 2021-2027, increased by €1.5 billion after the revision of the MFF in 2024. It takes the form of subsidies for cooperative programmes. The grants are paid to entities (companies or organisations involved in defence, research laboratories, etc.). It provides co-financing (often 80% or even 100%). One third of the budget is allocated to research and two thirds to development support. The average level budgeted since the creation of the EDF has been just under €1 billion a year, but the allocation should increase by the end of the programme: €1.4 billion budgeted by 2025.

b) An innovative approach

This originality cannot be understood without comparison. The European Union intervenes in the military field mainly through two funds: the EPF (operations) and the EDF (industry). The two funds follow different procedures. One is financed by the Member States, with a unanimous decision to intervene; the other is financed by the European budget, with an annual envelope set by the budgetary authority (Council and Parliament) and a decision by the Commission, which is ultimately responsible for selecting proposals, and the coordinating entity. The budgetary issue is secondary, as the levels of contribution are comparable. But the decision-making authority is not the same.

The European Commission is assisted by a committee comprising representatives of the Member States[22], which contributes to the development of the work programme, the call for proposals and the selection of projects. It is assisted by a group of ‘independent experts’ from ‘as wide a range of Member States as possible’ who are responsible for assessing the projects’ ethical aspects. When it comes to military issues, the committee's assistance plays a decisive role.

c) A useful fund for European integration

The EDF is one of the most interesting budgetary tools, and one in which the European Union is fully legitimate. Since the funds, like the research programmes, promotes European cooperation, which is not the case for the main budgetary policies like the Common Agricultural Policy and cohesion policy, which are redistribution policies. The European Union is about getting people to work together, not just redistributing money via the European budget[23]. The EDF does this.

d) Significant Potential

The EDF is helping to strengthen the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB). But with €9.5 billion, the European Union remains a secondary player. Several voices have called for a change of scale. In January 2024, Commissioner Thierry Breton spoke of a €100 billion equipment plan. In June, the President of the European Commission estimated that the European Union would need €500 billion of investment in the defence sector over this decade. Whatever the level of the ‘Community’ share (20, 50 or 100%?), the European Union's involvement will obviously have a different dimension. Even if the question of financing (by borrowing?) remains unanswered. This is why the experience of the EDF must be analysed carefully.

B - Mid-term review (2021-2023) of European Defence Fund support

1/ Main results[24]

Three financial years have elapsed since the creation of the EDF (2021, 2022, 2023). One hundred and sixty-two programmes have been financed to the tune of €3.1 billion.

- The EDF has become part of the industrial landscape. Since calls for proposals began, the fund has received 512 proposals. The number of applicants for European funding is growing all the time.

- It finances projects of all sizes (from €3 million to €100 million) and across a broad spectrum, from satellites to aircraft cockpits and infrared vision. But the majority are small programmes of less than €5 million.

- The Commission has ensured that coordination benefits entities in almost all Member States.

- The objective of cooperation has been achieved. The consortia funded bring together an average of seventeen entities.

2/ Comments on the geographical distribution of the programmes selected

a) A wide range of coordination arrangements

Of course, countries with a military industry have been the main beneficiaries of Fund allocations and coordination (France, Spain[25], Greece, Italy, Germany). However, the Commission has also appointed coordinating bodies (Romania, Slovenia, Portugal, Ireland, Cyprus) from countries that are relatively unknown for their military industry. This distribution, in fact, this dispersion, needs to be analysed.

First hypothesis: competition. Even if it is no longer the supreme guide to European action, competition still permeates the mentality in the Commission’s and European choices. We need competition, including supporting the small against the large, the potential nuggets against the established leaders. There has to be room for new industrialists[26].

The second hypothesis is to take advantage of budgetary support for the armaments sector to bring about the emergence of a new European industrial landscape. Modern warfare has seen the combination of high tech and low cost, which opens up the field of selection. So, it would be less a question of seeking work allocation than of developing a defence industry wherever possible. Is the EDF the right lever?

The third hypothesis is that the selection of projects is above all the result of a political display and choice to ensure that each State is not forgotten and feels involved in this process of European cooperation, which has always involved a trade-off between efficiency and balance. The Permanent Structured Cooperation (PSC) decided in 2017 is an example of this difficulty between supporters of a PSC centred on a hard core and supporters of a PSC extended to the greatest number. This is the approach that prevailed at the time, and which has been confirmed with the EDF. The assistance of the committee responsible for making a selection is no doubt not unrelated to this situation.

b) The situation in three countries can be described in detail

France, which has been able to compete in the armaments field with the major players[27], is the main beneficiary of the EDF in terms of coordination and participation. Thales and Airbus Defence alone, two examples of European cooperation, account for 25% of the coordination of projects worth more than €20 million. In strictly budgetary terms, this is a good operation. France contributes 17.2% to the financing of the European Union budget, and the EDF is a way of improving its rate of return, which is on average only 11%[28].

Germany is not and does not see itself as a military power. But it does have a military industry and long experience of cooperation. Its place in EDF coordination may come as a surprise. Although it is the largest contributor to the fund, it accounts for only 7% of European coordination[29]. Should we see this as a sign of distancing from cooperation or even from European defence issues? Current priorities lie elsewhere.

Poland coordinates very little, once a year on minor projects. This does not mean that Warsaw has no military industry[30] but its involvement in European cooperation is limited. In terms of military equipment, Poland has chosen other solutions.

3/ Questions for the future

The European Defence Fund has reached cruising speed. On current bases, the remaining 5 billion to be distributed over three years would finance 270 projects. Before it becomes a kind of benchmark for future funding of military capabilities, a number of questions need to be asked.

a) European cooperation vs bilateral cooperation?

The military industry is used to cooperation that is chosen rather than imposed. It does not always do so spontaneously or with the fervour of the forerunners of European integration. The experience has not always been conclusive. There has been no shortage of setbacks[31].

Current cooperative ventures take a long time to establish, and sometimes fail simply because of scheduling problems, but they are based on armed forces’ requirements. There is a great deal of ongoing cooperation. Many states continue to encourage bi- or multilateral cooperation, but with a small number of operators. Even if the partners change. Traditional cooperation with Germany remains fundamental but seems to need to be balanced with other countries[32], perhaps for fear that imposed European cooperation would be to the detriment of the traditional bilateral type, which manufacturers consider to be more effective.

b) Ritual criticism of procedures

Criticism regarding fraud goes back a long way, but it has been devastating. Since then the Commission has surrounded itself with procedures that industrialists are happy to complain about, especially those who have not been selected. 32% of proposals are selected, meaning 68% are not. While the cost of entry is the same (finding partners, if possible from the new Member States, agreeing on sharing and the timetable, etc.), for someone familiar with cooperation, ‘the process is so cumbersome (like traditional European R&T funding) that the analysis of the awards reflects the capacity of companies to invest in such a bureaucratic process rather than the real interest of industry’.

c) Who decides and how? A federal leap forward?

The Commission decides on the allocation of funds after receiving the opinion of a committee comprising representatives of the Member States. This broad composition means that there are different, even divergent, opinions on the themes to be prioritised, the projects submitted and the entities participating in the consortiums. It is no insult to anyone to admit that, in the military field, resources, the proximity of threats, but also national needs and experiences are diverse. The committee adds a filter that misses the point. Is it up to a committee of experts to select the armies' armament programmes, taking care not to forget anyone but omitting the needs of the armies and the objectives defined by the States?

The transfer of decision-making authority from the States to the Union brings us back to the federal question. In 2019, during the creation of the EDF, Alain Lamassoure presented an amendment advocating the transfer of armaments competences to the Union: ‘Defence clearly illustrates that greater efficiency could be achieved by transferring to the EU certain competences that are currently those of the States, as well as the related appropriations’. The amendment was rejected, but the EDF is a substitute.

This is a worrying development. But governments and industry still need to come up with a credible alternative. The latest cooperation announced with Germany concerns the Franco-German MGCS tank of the future. A political cooperation venture[33] signed after seven years of preparation and intended above all to counter the Breton Plan (100 billion) to show that bilateral cooperation remains active. But a few months later, the programme already seemed compromised[34].

d) The protective shadow of the American ally

Supporting European manufacturing is one thing. Selling it to Europeans is quite another. Cooperation with NATO is a systematic reference in all defence-related initiatives. Nothing could be more normal. But the situation raises questions when the obligatory reference becomes the regular supplier. 80% of Member States' defence investments since 2022 have been made with suppliers from third countries, 63% of which come from the United States.

The Commission is in an ambiguous position. In March 2024, it called on the Member States to ensure that at least 50% of their defence investments were made within the EU by 2030, and 60% by 2035. But in October, its President spoke of the single defence products market. In the European Union, a single market also means an open market, which is causing concern among manufacturers.

80% of arms purchases made elsewhere! Is this due to the insufficient quality and availability of European products, or are other factors at play? “Arms purchases have an eminently political dimension, in that they are often motivated by the purchasing country's concern to obtain security guarantees from the selling country.”[35] While France advocates a European preference, several countries are refusing to restrict third-party intervention. This is the clear choice of the two main buyers, Germany and Poland.

The EDF ‘contributes to the interests of the Union’. But for others, the priority is to secure alliances. Interests versus priorities: a crucial dilemma for the future of European defence.

Annexes

Annex 1

Expenditure in support of the arms industry

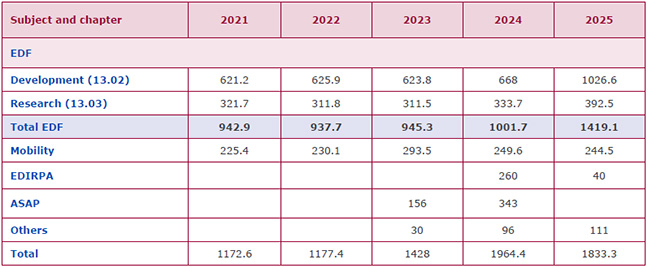

Table 1: Military expenditure in the European budget (commitment appropriations, million €)

Sources : EU budgets, compiled by the author for the Foundation

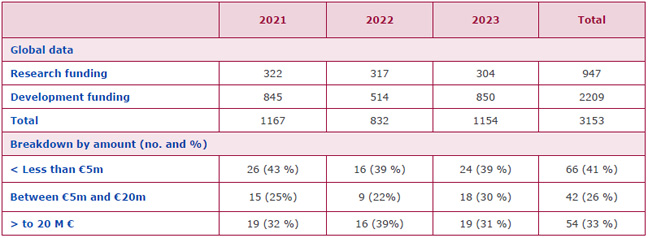

Table 2: EDF Support 2021-2023. Financial Data (million €)*

Sources : Compilation by the author for the Foundation. The Commission's allocation decisions relate to programmes from year n-1, which explains the time lag with the EU budget.

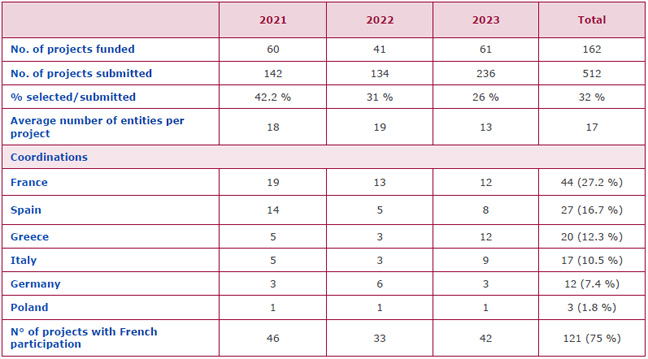

Table 3: EDF Support (2021-2023). Economic and industrial data

Sources : Compilation by the author for the Foundation

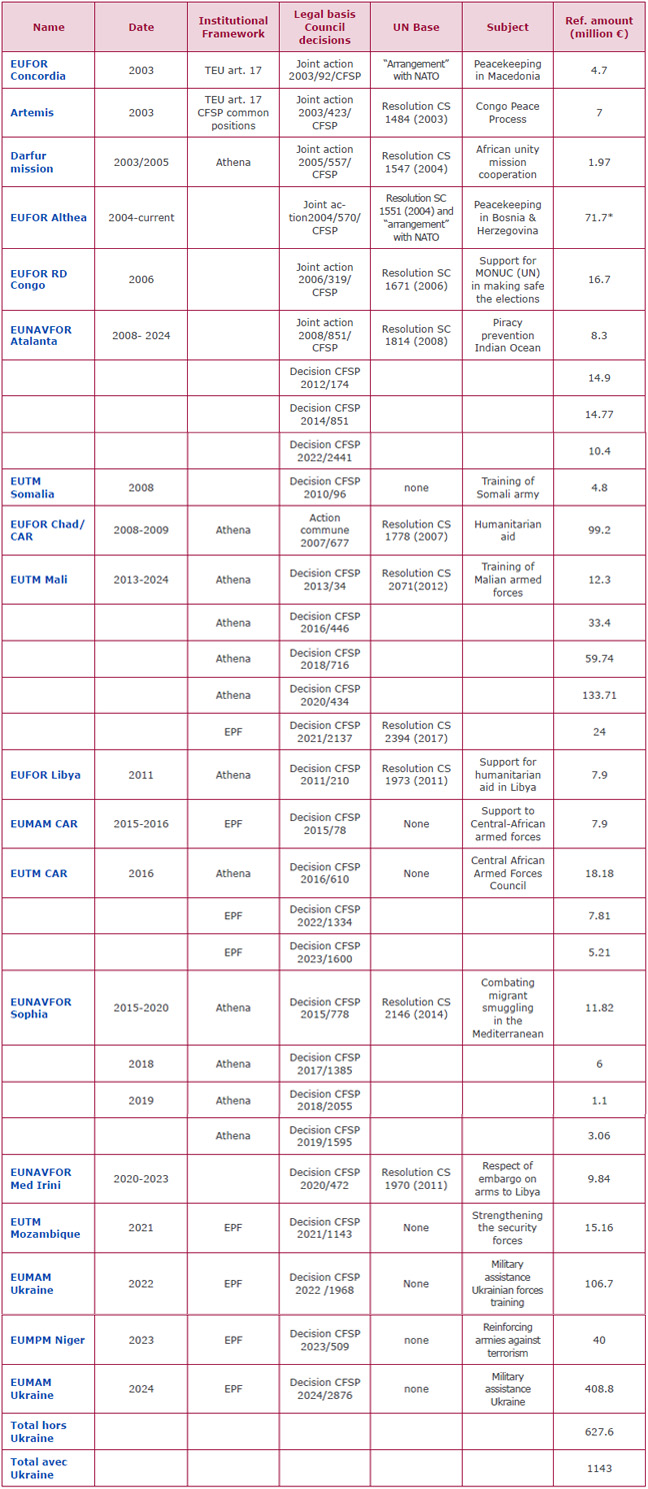

Annex 2

Costs of European Union military operations

Sources : Decisions CFSP, compilations by the author for the Foundation

*Cost provided for in the 2004 Joint Action. At the time, the European force consisted of 7,000 people. The force was resized in

2007 to 1400 people. The cost is not specified.

[1] See L’Union européenne et les Balkans, Revue de l’Union européenne, 2019

[2] The so-called “Berlin Plus” agreement adopted on 17 March 2003.

[4] The so-called Petersberg missions were adopted within the framework of the WEU in 1992 and included in the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997.

[5] Implementation of a permanent structured cooperation; strategic autonomy set out at the Versailles summit in March 2022, etc.

[6] Security Strategy, State of the Union address in 2016, Whitepaper on Defence etc.

[8] Unanimity modulated by constructive abstention; a procedure introduced by the Treaty of Amsterdam. It allows a State not to approve an action without blocking the decision of the others.

[9] External operations generate three types of expenditure: administrative costs borne by the European budget, operational costs borne by the States taking part in the operation, and common operational costs borne by the collective financing mechanism.

[10] The funding is shared between the Member States based on their gross national product, with the exception of the Member States that abstained when the joint action was adopted.

[11] Decision (CFSP) 2004/197 of the Council dated 23 February 2004

[12] Unanimity does not preclude effectiveness. Military assistance to Ukraine was organised in a matter of weeks “Who would have bet on European unity from the first day of Russian aggression in Ukraine and on massive military support from the European Union? We did.” Emmanuel Macron, 25 April 2024

[13] Supporting powers are defined in Article 6 of the TFEU.

[14] Defence industry support funds are based on Article 173 of the TFEU.

[15] Elsa Bernard, La communautarisation de la défense européenne dans le contexte de la guerre en Ukraine, Quarterly European Law Revue 2023

[16] L’UE avance sur le plan militaire mais de façon désordonnée, Le Monde, 15 May 2024.

[17] Draft Finance Bill for 2025, annexed document Les relations financières avec l’UE.

[18] Information report on the defence industry by MM Jean-Charles Larsonneur and Jean-Louis Thiériot, May 2024

[19] Art 42 -3 al 2 of the TEU.

[20] For example, 10 Caesar guns in France, 5 in Italy and 5 in Romania.

[22] The Committee is assisted by the European Defence Agency and the European External Action Service.

[23] The first area of European solidarity is the budget. Annual financial transfers between contributor and beneficiary countries represent around 40 billion euros per year.

[24] See annex 1 tables 2 and 3

[25] Spain is the leading country in military matters, joining the traditional cooperative ventures. As in the case of the SCAF programme for the air combat system of the future.

[26] There are centres of excellence in Lithuania, the European "hot spot" for cyber security.

[27] See the SIPRI report

[28] The net balance, in this case the net contribution, is €7.5 billion on average over three years.

[29] Germany is more present in single participations, ranking second after France.

[30] The PGZ consortium includes shipyards, electronics companies, armaments and munitions. The WB Group is renowned for its small drones and remotely operated munitions (kamikaze explosive drones), which are manufactured and exported in hundreds of thousands of units.

[31] Cost explosion, delays, multiple versions to take account of national specifications. See in particular the Airbus A400 M setbacks, which have been commented on many times.

[32] Cf Treaty of January 2023 between France and Spain on defence cooperation, announcing cooperation in the area of capabilities. Parliamentary report by Nicolas Forissier

[33] Le très politique char franco-allemand, Slate 26 May 2024

[34] Le projet franco-allemand de char du futur prend du retard, Laurent Lagneau, Zone militaire, October 2024.

[35] Information report on the defence industry AN May 2024, Op. cit.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :