Multilateralism

Aifang Ma

-

Available versions :

EN

Aifang Ma

Boya Postdoctoral Scholar and Lecturer, Peking University, Associate Researcher, Sciences Po Paris

In 1964, when the Canadian pioneer of media studies, Marshall McLuhan, argued that media is an extension of man, he did not foresee that future media, at the beginning of the 21st century, would produce increasingly pernicious effects[1]. While media have indeed extended human capacities, they have also shown to be generators of complicated social and ethical problems. In the same year philosopher, Herbert Marcuse, who analysed relations between Man and Machine from a deeply pessimistic viewpoint. His predictions seem to be corroborated by what we are now experiencing: the easy life made possible by technological progress has progressively gnawed into the individual critical reasoning. Instead of imposing their control over technologies, human beings are increasingly at their mercy. The domination of technology over individuals is all the stronger, since it seems harmless and is pleasant to use.

In this context, the regulation of digital technologies[2] is flourishing in autocracies and democracies alike. Its importance goes far beyond the need of authoritarian regimes to cut off the transmission of destabilising content. It is universal since digital technologies set common challenges to national governments: illegal collection of users’ personal data, precarious working conditions for gig workers, monopolistic practices of large platforms, threats to human dignity and domestic security. These problems are causing trouble to all governments around the world.

This article aims to be pragmatic. Beyond differences in political regime, it studies the regulatory approaches of the three largest digital economies in the world: China, the United States, and the European Union. The three models can potentially hinder or stimulate the development of digital technologies without necessarily opposing each other.

In the European Union priority to the protection of citizens’ rights

Regulatory agencies of the EU and the Member States of the EU operate together within the institutional layout of the EU, and European regulators have larger competences than national ones. Responsibilities of the regulators on these two levels differ depending on the regulatory fields in question. Article 3, paragraph 1, (TFEU) stipulates that “the establishing of the competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market”. Therefore, it is in the regulatory turf of European regulators to fight anticompetitive practices of tech giants.

The EU and its member states have shared competences in several fields, including consumer protection and trans-European networks. However, the EU prevails over its member states when it comes to legislating in these fields: “The Member States shall exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has not exercised its competence. The Member States shall again exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has decided to cease exercising its competence” (article 2, para 2, TFEU). The EU can also take measures to ensure coordination of the employment policies of the Member States, “in particular by defining guidelines for these policies” (article 5, para 2, TFEU). This provision therefore gives it the opportunity to set the political direction for digital work.

The protection of citizens’ rights is central to digital regulation in Europe. This is reflected above all by the unequal power relations between tech firms and citizens: the latter obviously prevail over the former. The way in which the EU regulates access to cyberspace can be understood as follows: limiting firms’ freedom so as to increase citizens’ freedom. Scholars like Adam Thierer have qualified the regulatory approaches of the EU and the USA respectively as “prudent regulation” and “permissionless regulation”. Under “prudent regulation”, new technologies cannot be used unless they have been proven to be harmless. “Permissionless regulation” follows an inverse logic: the adoption of new technologies is automatically authorized, except when a sufficient number of cases demonstrate their secondary effects.

Digital firms operating in the European single market face multiple constraints, and violation of the rules expose them to extremely severe sanctions. The EU is a pioneer in terms of the introduction of protective laws for its citizens. From GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), DGA (Data Governance Act), DSA (Digital Services Act), DMA (Digital Markets Act) to the AIA (Artificial Intelligence Act), the EU has shown itself to be a global example of digital regulation. It has institutionalised several innovative methods in this area: the right to be forgotten[3], definition of the dominant market position by combining qualitative and quantitative criteria, and the risk-based regulation of AI, to name only a few. These practices are being imitated by other countries and regions in the world. Among all the jurisdictions, the EU is undoubtedly the one with the most up-to-date regulatory framework of the digital economy. The declaration made by Thierry Breton, former Commissioner of the Internal market, showcased the EU’s pioneering spirit: “It is high time that Europe fixes the rules of the game at the upstream level, in order to guarantee the fairness and openness of the digital markets”.

Deterrence is first and foremost financial. The GDPR, which took effect in 2018, is a fundamental text on the protection of personal data. To ensure that tech firms comply with new rules, it laid down record-high fines: based on the severity of its transgressions, a firm must pay between 2% and 4% of its worldwide annual turnover from the preceding financial year. DSA and DMA also include high financial sanctions for rebellious firms. Adopted in January and July 2022, these two regulations created a system of asymmetrical obligations according to the size of digital platforms, with highest sanctions applicable to “gatekeepers”[4]. Fines can total as much as 10% of gatekeepers’ worldwide annual turnover. They can even rise to 20% for repeat offenders. The European Commission can inflict mergers bans and demand disinvestment of gatekeepers which have violated the rules three times or more.

On 6 September 2023, for the first time since the adoption of the DMA, the European Commission designated 6 digital firms as gatekeepers: Alphabet, Amazon, Appel, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft. It has the right to designate new gatekeepers and examine their compliance every three years. With the DMA, gatekeepers are forbidden from undertaking self-preferencing on their platforms. They cannot prevent users from unsubscribing from their services or uninstalling their applications or pre-installed software. They are prohibited from re-using a user's personal data for targeted advertising purposes without the user's explicit consent.

Of course, the reason why the European Union has imposed this binding framework is also linked to its need to protect its digital businesses from the aggressive practices of the American 'giants'. The vast majority of European platforms are small and medium-sized, making them difficult to categorise as gatekeepers. Nevertheless, it has to be said that by increasing the cost of monopolistic practices by gatekeepers, the DMA will protect the innovation of small and medium-sized European platforms. This benefits consumers by giving them greater diversity of choice.

The DSA lays down differentiated treatment for digital platforms: the largest of which will assume the largest responsibilities. In April 2023 the European Commission designated 17 “very large online platforms and search engines” (VLOSEs) and instituted a restrictive regulatory framework for them. They must inform users of the reasons for which certain information is recommended to them; users must be given the possibility of refusing personalized services based on precise profiling; it is easier than before to flag illegal content, and large platforms must deal with these problems promptly. Platforms must label all advertisements and indicate the identity of advertisers. In October 2023, some of them submitted their transparency reports.

The EU is nowadays a pioneer of the digital governance. However, the fact that it is trying to make its regulations fashionable enough to regulate even the most recent developments in the digital economy represents a major risk. This is because the EU needs to update its regulatory framework frequently, which increases regulatory costs and legislators’ pace of work. As the case of the AIA (AI Act) demonstrates, the EU rapidly introduced stringent rules that are directly applicable to the Member States whilst the economic, social and ethical impact of AI is still unclear. The implementation of the AIA at this relatively early stage could make this regulation obsolete fast, except if the EU’s regulators can holistically anticipate the influence that AI will have. Therefore, it would be more prudent to start with more flexible rules to incrementally introduce stricter levels of regulation when the impact of AI becomes clearer. To pursue a perfect match between regulations and reality implies excessively intensive regulatory speed.

Pre-emptive regulation by the EU does not always help the growth of digital platforms. Its deterrent effect tends to discourage digital firms from investing in technological innovation. If tech firms take high risks of being sanctioned due to their activities, it is logical that they hesitate to try out new methods or develop new technologies. Highly intensive regulation then becomes a constraint for firms, and ultimately harms citizens. It is certainly important to stem the negative consequences which go hand in hand with the digital economy, but it is even more important to build a favourable environment for the growth of tech firms. Digital laws and policies in Europe need to be simultaneously facilitative and restrictive.

In China, national security first

China is the second largest digital market in the world. The development of the digital economy there is now very advanced. The wide use of AI in the organization of the Asian Games in Hangzhou in September 2023 bears testimony to the deep embeddedness of digital technologies in Chinese citizens’ daily life[5].

A major paradox in China lies in the coexistence between a dynamic digital economy and a strict legal framework. In the book China as a Double-Bind Regulatory State, this particular feature of Chinese digital governance can be in two parts: political and economic. The Party-State uses two contradictory approaches in these fields. While economic domain unfolds in a decentralized way and aims to realize the objectives favourable to society, including technological innovation, political regulation is conducted in a centralized manner. Spearheaded by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) since 2014, it aims first and foremost to achieve the goals which benefit above all the regime, including, among others, national security, social stability, and the Party’s leadership in the ideological sphere.

China shares several similarities with democratic countries in the economic realm. Regulatory convergence is gradually taking shape in terms of the accountability of digital companies, anti-trust legislation and the protection of personal data. However, in cases where platforms’ violation of rules damages national security or social stability, the Party-State quickly responds and sends national regulators to the frontline. Economic interests are relegated to a secondary position, at least temporarily. They are pursued again once the objectives of national security are guaranteed again.

Alibaba's trajectory represents the expansion of China's digital economy over the last thirty years. The company has always maintained cordial relations with the Chinese authorities, which has often earned it preferential treatment compared with less influential digital firms. In 2010, when the State Administration for Industry and Commerce wanted to make small traders on C2C platforms pay tax, Alibaba asked Lü Zushan, then governor of Zhejiang, for help. After his intervention, the national regulator abandoned its plan. However, the preferential treatment was suspended when the activities of Alibaba were found to be at odds with the regime’s security. In this precise case, local authorities that maintained symbiotic relations with Alibaba were powerless, unable to lend a helping hand to their protégé.

On 24 October 2020, Jack Ma, then president of Alibaba, expressed highly controversial ideas in his speech delivered at a Summit in Shanghai: he criticized the “pawnshop mentality” of Chinese state-owned banks and advocated a more liberal regulation of the financial market in China especially since the Chinese financial market had not yet formed a coherent system. His vehement comments led to serious consequences: apart from the abrupt interruption of the IPO of its subsidiary, Ant Financial, Alibaba was fined around €2.6 billion in April 2021, the largest fine ever imposed on a company based in China[6].

The misfortune of Alibaba and its chairman can, to a large extent, be explained by the contradiction between the priorities of the Party-State, on the one hand, and the financial regulatory framework championed by Jack Ma, on the other. At that time, the trade war between China and the USA was in full swing. Therefore, the liberalisation of the financial regulation advocated by Jack Ma was not feasible in China, because it risked increasing geopolitical uncertainty for the country.

The centrality of national security regarding the activities of netizens in China has been widely debated in academia since the 2000s[7]. Although scholars have held divergent opinions on Chinese netizens’ capacities to circumvent censorship, as well as the potential of the internet to liberalize China, they have agreed that the Party-State tends to tighten information control when online content could provoke large-scale destabilisation[8]. In almost all cases, the priority of national security as the goal of digital regulation is incontestable in Chinese digital legislation.

With the creation of the Cybersecurity and Informatisation Small Leading Group (CI-SLG) in 2014, changing its name to the Central Cybersecurity and Informatisation Commission (CCIC) in 2018, the party institutions have progressively moved to the forefront of regulating digital activities in China. This institutional change is unique in that it runs counter to the division of labour between the institutions of the Party and those of the State: while the former are used to taking decisions behind the scenes and keeping a low profile, the latter publicly proclaim these decisions and implement them. The way the CCIC operates hardly corresponds to this convention. This inter-ministerial coordinating body has decision-making powers over every area of digital activity. Party institutions are more concerned with the political framework. The fact that they are directly in charge of digital regulation will make national security an even more central objective in China.

The United States: freedom above all else

Freedom is the keyword of digital regulation in the United States. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is a fundamental bill in the defence of freedom. Incorporated into the Bill of Rights in 1791, it intends to protect the freedom of religion and the freedom of expression against the interference of the executive power and the Congress. The latter was forbidden from establishing any national religion and damaging the freedom of expression and press. The government must provide significant grounds to justify its interference in the voice of American citizens. Over time, American jurisprudence has clarified the categories of the contents that the First Amendment did not protect, in contrast with the ambiguity of content regulation in authoritarian contexts[9].

Citizens’ activism, likewise that of civil associations and digital firms has played an important role in raising the freedom of expression as a fundamental goal in the governance of the internet use in the USA. In the 1990s and the 2000s, regulatory attempts on the part of the American government met with strong opposition. These intrusions were largely construed as substantiating regulators’ hunger for power. John Perry Barlow, co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), was an emblematic figure in the defence of the freedom of expression. He vehemently criticized the American Congress for having adopted the Telecom Reform Act in 1996. In his opinion, those who had adopted this law did not understand the difference between cyberspace and the real world: “This law has been implemented against us by people who have no idea of who we are, or where our conversations are being conducted. It is [...] as if ‘illiterates told you what you could read’”.

American jurisprudence is known for defending citizens’ freedom of expression. In several important court rulings, including Reno v. ACLU in 1997, Elonis v. United States in 2015, and Mahoney v. Levy in 2021, courts at different administrative levels opted to champion citizens’ online freedom of expression. Restrictions on freedom of expression do exist, but they are meticulously detailed, scrupulously scrutinised and continually redefined through bitter negotiations between the authorities and civil society.

In the same way as the protection of citizens’ freedom of expression, the freedom of digital platforms to disseminate content is also protected. The Communications Decency Act (CDA), also called Title V of the Telecommunications Act, was adopted in 1996. It initially intended to constrain adolescents’ access to pornographic content online. In the aftermath of strong challenges by civil society, the U.S. Supreme Court deleted several provisions from the CDA. However, Section 230 remained and subsequently became one of the most useful instruments in the protection of digital platforms. It stipulated that content providers and users of online interactive services should not be treated as editors of information. This principle was consolidated by two court rulings: Zeran v. American Online, Inc. in 1997 and Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc., in 2009. As a result, intermediaries were exempted from the responsibilities that information editors normally assumed.

Regulators’ dilemmas emerge when corporate freedom hinders that of citizens, and vice versa. The case of the USA differs from that of the EU, since American regulators seldom defend citizens’ freedom of expression at the price of sacrificing the freedom of tech firms. Given the dependence of internet users on platforms, the latter are better equipped to prevail over citizens when the freedom of the two types of actors enter into conflict. The weak power position of internet users in the USA can be explained by three factors:

First and foremost, platforms in the USA engage in aggressive lobbying to ensure that they are not disadvantaged by to-be-adopted regulatory rules. American firms employ several methods to build relations with high-ranking officials. They create think-tanks to spread their claims under a cover of neutrality and fund research whose results go the way they wish. In recent years, American firms have advanced using new methods: exploring the grey zone of the law, rapidly acquiring huge popularity with which to resist regulators, recruiting former government officials as advisors, to name only a few. In 2010, Google launched “Google Ideas” and appointed Jared Cohen, former employee of the State Department, as the first director of the initiative. Conversely, citizens have less time, less resources, and less expertise to initiate this type of activity to build their influence.

Then, platforms have several cards to play in platform-user relations. Since sensational content is more likely to drive up online traffic, platforms deliberately opt not to moderate or under-moderate online hate or extreme speech. In the great majority of cases, commercial motivation has greater explanatory power than lofty motives (e.g., defence of citizens’ freedom of expression) to explain laxist content moderation practices. The consequence of the immunity laid down in Section 230 is that digital platforms can act according to their own will and become quasi-sovereign in terms of content moderation.

And finally, digital platforms take citizens on board as their allies to resist restrictive legislation. One of the strategies that digital platforms frequently employ is to build huge popularity in the first place and to capitalize on this to resist drastic regulators. In the case of Uber, when Virginia’s Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) asked the firm to cease its illegal activities, Uber informed its Virginia-based users, providing them with the contact information of the official behind this decision. Hundreds of users harassed the official by emails. 48 hours later, the transportation secretary of Virginia required the DMV to stop interfering in Uber’s business affairs. Therefore, contrary to China and the EU, it is difficult to put limits on the expansion of highly popular digital platforms in the USA.

Three Models of Digital Regulation

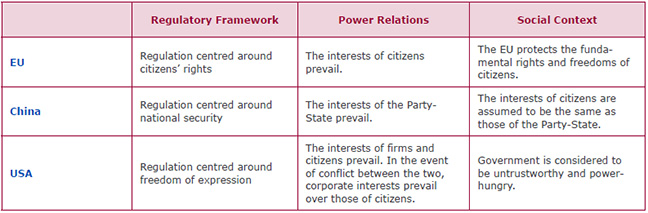

Based on the analysis of the power relations between state, firms, and citizens in digital legislation, the models applied in the EU, China, and the United States are centred respectively around citizens’ rights, the preservation of national security, and the freedom of expression. This typology shows that political regimes alone cannot reliably predict the way in which a given national government regulates digital technologies or its digital economy. Regulatory objectives must be added to the political regimes to build a complete typology. For instance, although both the EU and the USA belong to liberal democracies, citizens are better protected in the former than in the latter. Table 1 summarizes the main features of the three models of digital regulation:

Table 1: Three Models of Digital Regulation

Source : adapted from Aifang Ma (2023)

The three models of digital regulation sometimes overlap. However, a hierarchy of standards exists, and this is difficult to inverse. This is reflected especially in the cases where objectives enter into conflict in the same jurisdiction. For instance, Chinese regulators can place citizens’ freedom of expression on a secondary level when the pursuit of this objective makes the defence of national security difficult to achieve.

The way in which other countries regulate their cyberspace can also be classified in one of the three models. For example, both Singapore and South Korea practice regulation centred on security. For this reason, they demonstrate similar regulatory patterns to China. In 2001, South Korea adopted the Internet Content Filtering Ordinance, requiring tech firms to undertake ex ante filtering of the content disseminated online. Contents glorifying North Korea are strictly forbidden. Canada practices digital regulation centred around freedom of expression. On the one hand, self-regulation of online content prevails in Canada, and professional guilds set related standards. On the other hand, the sanctions against firms that contravene the rules are not a deterrent, implying they can pursue commercial interests at a lower cost at the expense of public interest. In the antitrust regulation of the digital economy for instance, the Competition Bureau of Canada inflicts a fine of 7 million euro to businesses for their first violations and 17.6 million euro for their second violation. These amounts are easily digested by large tech firms.

Australia however regulates cyberspace in a similar manner to the European Union. The Australian Communications and Media Authority, the regulator of the country’s digital platforms, can impose a fine of 11,000 dollars per day on the firms that have failed in terms of their due diligence regarding illegal content. Individuals found guilty can be imprisoned for 10 years. In addition, the Australian Parliament adopted “News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code” on 17 February 2021. With this law, Australia became the first country in the world to require digital platforms to pay fees when they use content produced by news organisations.

***

Models of digital regulation evolve constantly. The globalisation of the digital economy has given rise to a kind of homogenization of the growth trajectories and practices of digital platforms. As a result, the latter have generated similar challenges for national and supranational governments. In this context, it cannot be ruled out that latent but constant tensions will progressively bring the models of digital governance closer to each other, at least in the regulation of large platforms. Will these models converge or diverge in the future? To answer this question, a watchful eye must be kept on homogenizing and heterogenizing factors. It is certain however that scholars should avoid investigating digital regulation exclusively based on the types of political regime, because the latter obliterates in one stroke of a pen the multiple nuances in the way in which platforms are governed.

[1] Screen additions, speeches which radicalise fundamentalist ideas, and hate speeches having pushed certain public figures to commit suicide. The suicide of the famous South Korean actress Sulli in October 2019, and that of other less famous individuals due to cyber bullying, illustrate the dark side of a hyperconnected society.

[2] Digital regulation refers to laws and policies aimed at framing and supervising the use of digital technologies and the Internet to ensure security, privacy and respect for online rights. It includes measures such as personal data protection, net neutrality and the fight against online hate speech.

[3] The European Union introduced the right to be forgotten in 2014 in the court ruling Google Spain SL, Google Inc. c/ AEPD and Mario Costeja Gonzalez of 13 May 2014.

[4] A “gatekeeper” denotes a tech firm which achieves an annual Union turnover equal to or above 7.5 billion euro in each of the last three financial years, or where its average market capitalization or its equivalent fair market value amounted to at least 75 billion euro in the last financial year. A gatekeeper must have at least 45 million monthly active end users or 10,000 yearly active business users in the Union and provide a core platform service in at least 3 member states.

[5] During the Games, robots were used to chase insects; androids played piano; driverless lorries transported ice; robot dogs walked among the visitors. The most spectacular scene was the holder of a digital torch bearer during the opening ceremony of the Games.

[6] After the failed IPO of Ant Financial, Jack Ma disappeared from Chinese media for more than 2 months, which led to multiple speculations. Some media outlets reported that the Chinese government had prohibited Jack Ma from leaving China. Others suggested that the billionaire had left for overseas. It was mid-January 2021 when Jack Ma re-appeared at a golf course of Sanya, capital city of Hainan.

[7] Refer to the publications of Guobin Yang, Yongnian Zheng, Séverine Arsène, Rongbin Han, and Yong Hu.

[8] Existing literature has extensively discussed information control in China. For this reason, the present article grants greater attention to the regulation of tech firms, a topic which has thus far attracted less academic attention.

[9] Certain speeches are not protected by the First Amendment, including incitements to illegal behaviour (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969), aggressive words against representatives of public order (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942), commercial communications (Central Hudson v. Public Service Commission, 1980), and obscenities (United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses, 1933).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :