Democracy and citizenship

Thaima Samman,

Benjamin De Vanssay

-

Available versions :

EN

Thaima Samman

Member of the Paris and Brussels bars, founder of SAMMAN Law Firm.

Benjamin De Vanssay

Member of the Brussels Bar

On top of all these initiatives and legislations, the European Commission has proposed two directives to the regulation on Artificial Intelligence (“Artificial Intelligence Act”, hereafter AI Act) is a landmark piece of EU legislation in the field of AI. One of its primary aims is to regulate the use of this technology in a number of areas based on a risk-based approach. In that respect, the AI Act sets gradual obligations for the different parties involved in the AI value chain depending on the level of risk that the use of AI raises in concrete use cases. The AI Act should therefore be viewed as a targeted intervention, and not a cross-cutting legislation like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The AI Act was adopted by EU co-legislators in May 2024 and will enter into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union on July 12. It will apply from August 2, 2026.

Meanwhile, the Commission has launched the AI Pact, a voluntary initiative inviting AI providers to comply with the key obligations of the AI Act in advance of its entry into force.

1. The AI Act: one piece in a complex AI regulatory puzzle

The AI Act is also part of a broader regulatory framework, which can be sketched out as follows:

• Data: on the one hand, there is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which restricts access to personal data to protect the privacy of individuals, and includes specific safeguards on profiling methods, and on the other, the EU Data Strategy, which aims to increase the sharing and availability of any kind of data to foster innovation. The latter encompasses several initiatives and pieces of legislation, including the Data Act, the Data Governance Act, regulations on the European Data Spaces and the Directive on Public Sector Information.

• Infrastructure: various initiatives have begun to step up the infrastructure capabilities of the EU, with the view to boosting innovation in AI, such as European Open Science Cloud, Quantum Flagship and the European High Performance Computing (EuroHPC). The EU Data Strategy (specifically, the Free Flow of Data Regulation and the Data Act) also aims to drive competition in the field of cloud computing and ensure secure data storage.

• Algorithms: the AI Act seeks to address certain risks stemming from the use of AI systems which are mostly related to how their algorithms work. In addition to the AI Act, the Commission plans to take targeted issue-driven initiatives in specific areas, such as the use of AI and algorithms in the workplace. It has, in fact, been mulling using the provisions on algorithmic management contained in the proposed Directive on platform workers as a blueprint.

establish a horizontal liability framework for AI systems: a revision of the Product Liability Directive, which seeks to harmonize national rules on liability for defective products, and an AI Liability Directive which shares the same goal for non-contractual tort-based liability rules.2. Summary of the AI Act

2.1 Scope and definitions

The AI Act has a very broad scope and a strong extraterritorial reach, as it would apply to any AI system having an impact in the EU, regardless of the provider’s place of establishment. Specifically, the AI Act would apply when the AI system is placed on the market or put into service in the EU, when a user is located in the EU or when the output is used in the EU.

AI itself is defined in very broad terms in the AI Act. It covers any “machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments”.

The AI Act distinguishes between AI systems and General Purpose AI models (GPAI), which are AI models trained with a large amount of data, using self- supervision at scale and which can competently perform a wide range of distinct tasks.

It is worth noting that the AI Act provides for several exceptions:

• AI systems and models that are developed and used exclusively for military, defense and national security purposes;

• AI systems and models specifically developed and put into service for the sole purpose of scientific research and development;

• Any research, testing or development activity regarding AI systems or models prior to their being placed on the market or put into service;

• AI systems released under free and open-source licenses, except where they fall under the prohibitions and except for the transparency requirements for generative AI systems.

2.2 The regulation of AI systems: prohibited and high-risk AI systems

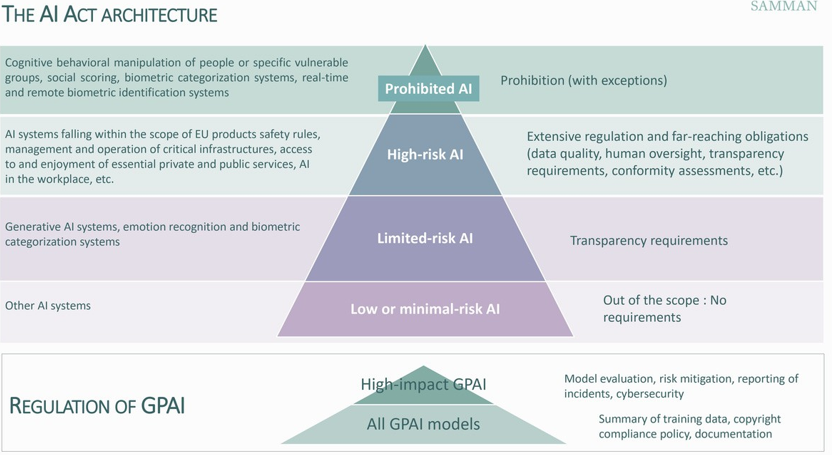

The AI Act distinguishes between four categories of use cases depending on their level of risk for health, safety and fundamental rights. Specific requirement applying to providers and users of these systems are attached to each category.

The AI Act also regulates GPAI models, though with a different approach, effectively establishing horizontal rules applicable to all providers of GPAI models falling within the scope of the regulation.

a) Prohibited AI practices

The AI Act prohibits the placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of the following AI systems (with exceptions for certain use cases):

• AI systems that deploy subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques;

• AI systems that exploit any of the vulnerabilities of a person or a specific group of persons due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation;

• Biometric categorization systems that categorize individually natural persons based on their biometric data to deduce or infer some sensitive attributes;

• AI systems for social scoring purposes;

• Use of ‘real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purpose of law enforcement, with some important exceptions;

• AI systems for making risk assessments of natural persons in order to assess or predict the risk of a natural person committing a criminal offence;

• AI systems that create or expand facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage;

• AI systems that infer the emotions of a natural person in situations related to the workplace and education, with some exceptions.

b) High-risk AI systems

The regulation of high-risk AI systems makes up the bulk of the AI Act. It sets out rules for the qualification of high-risk AI systems, as well as a number of obligations and requirements for such systems and the various parties in the value chain, from providers to deployers.

I. Qualification of high-risk AI systems

The AI Act qualifies as high-risk some AI systems that have a significant harmful impact on the health, safety, fundamental rights, environment, democracy and the rule of law. More specifically, the AI Act establishes two categories of high-risk AI systems:

• AI systems are caught by the net of EU product safety rules (toys, cars, health, etc.), if they are used as a safety component of a product or are themselves a product (e.g. AI application in robot- assisted surgery);

• AI systems listed in an annex to the regulation (Annex III). This Annex provides a list of use cases and areas where the use of AI is considered to be high risk. It may be amended or supplemented by delegated acts adopted by the European Commission on the basis of certain criteria. In short, the following areas and AI systems are concerned:

o Biometrics: remote biometric identification systems, some biometric categorization systems, emotion recognition systems;

o Critical infrastructure: AI systems intended to be used as safety components in the management and operation of critical infrastructure;

o Education and workplace: some AI systems used in education and vocational training; AI systems intended to be used for recruitment or selection of job candidates or to make decision in the work relationship;

o Access to essential services: AI systems for the access to and enjoyment of essential private services and essential public services and benefits;

o Law enforcement, justice, immigration and democratic processes: migration, asylum and border control management; administration of justice and democratic processes.

The AI Act also provides the possibility for providers of high-risk AI systems to demonstrate that their systems are not high-risk (dubbed “the filter”) and do not materially influence the outcome of the decision- making process. To this end, providers must demonstrate that they meet at least one of the following conditions:

(a) the AI system is intended to perform a narrow procedural task;

(b) the AI system is intended to improve the result of a previously completed human activity;

(c) the AI system is intended to detect decision- making patterns or deviations from prior decision-making patterns and is not meant to replace or influence the previously completed human assessment, without proper human review;

(d) the AI system is intended to perform a preparatory task to an assessment relevant for the purposes of the use cases listed in Annex III.

II. Main requirements for high-risk AI systems and obligations for parties in the AI value chain

First, the AI Act lays down a series of requirements for high-risk AI systems:

• Risk management: establishing a risk management system throughout the entire life cycle of the HRAI system;

• Data governance: training the system with data and datasets that meet certain quality criteria;

• Technical documentation: Drawing-up technical documentation that demonstrate compliance with the AI Act before the placing on the market ;

• Record-keeping: enabling the automatic recording of events (‘logs’) over the duration of the lifetime of the system;

• Instructions for use: ensuring that deployers can interpret the system’s output and use it appropriately, including through detailed instructions;

• Human oversight: developing systems in such a way that they can be effectively overseen by natural persons;

• Accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity: developing systems in such a way that they achieve an appropriate level of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity.

Second, the AI Act lays down a series of obligations for the different parties involved in the value chain, namely the providers, importers, distributors and deployers, along with rules to determine the distribution of responsibility when, for instance, one of these parties make a substantial modification to an AI system.

Most of the obligations are placed on providers, including, as regards:

• Compliance and registration: the obligation to register their systems in a dedicated EU database and draw up the EU declaration of conformity;

• Quality management system: the obligation to put in place a quality management system that ensures compliance with the AI Act;

• Documentation keeping: the obligation to keep at the disposal of national competent authorities a set of documentation (technical documentation, history with notified bodies, etc.);• Logs: the obligation to keep the automatically generated logs for a period appropriate to the intended purpose of the HRAI system, and at least 6 months;

• Corrective actions and duty of information: the obligation to take immediate measures in case of non-compliance with the AI Act and inform the market surveillance authority.

The other parties in the value chain are mostly responsible for ensuring that the AI systems that they distribute or incorporate in their own services are compliant.

Additionally, when the deployer is a public body or a private operator providing essential services, it is required to carry out a fundamental rights impact assessment.

c) Limited risk AI systems

This third category applies to providers and deployers of generative AI systems and deployers of emotion recognition or biometric categorization systems, which must inter alia comply with the following transparency requirements:

• Chatbots: informing the natural persons concerned that they are interacting with an AI system;

• Generative AI: ensuring that the outputs are marked in a machine-readable format and detectable as artificially generated or manipulated (watermarking);

• Deepfakes: labelling the content as artificially generated or manipulated or informing people when the content forms part of an evidently artistic, creative, satirical or fictional work or program;

• Generated news information: disclosing that the content has been artificially generated or manipulated, unless it has undergone human review or editorial control.

2.3 Regulation of general purpose AI (GPAI)

The AI Act provides for a two-tier regulation of GPAI models. The first layer of obligations applies to all GPAI models, while the second layer applies only to GPAI models with systemic risks.

In both cases, the Commission retains significant powers to determine how compliance with the requirements will be achieved. It will be able to work with industry and other stakeholders to develop codes of practice and harmonized standards for compliance

a) Horizontal requirements for GPAI models

Under the AI Act, the following obligations are placed on the providers of GPAI models, regardless of whether their model are used in a high-risk area:

• Drawing up and keeping technical documentation (inter alia training, testing process and evaluation results);

• Providing documentation to users integrating the GPAI model in their own AI systems (including information about the limitations and capabilities of the model);

• Putting in place a policy to respect EU copyright law;

• Publishing a detailed summary of the content used for training the model.

However, providers of non-systemic open source models are exempt from the first two obligations and the definition of open source is narrow as it only concerns “models released under a free and open license that allows for the access, usage, modification, and distribution of the model, and whose parameters, including the weights, the information on the model architecture, and the information on model usage, are made publicly available”.

b) Requirements for GPAI models with systemic risks

The AI Act defines GPAI models with systemic risks as ones with “high-impact capabilities” or, in other words, the most capable and powerful models.

Pursuant to the AI Act, any model whose cumulative amount of computation used for its training measured in FLOPs is greater than 10^25 should be presumed to have “high-impact capabilities”. However, the regulation leaves significant leeway for the Commission to rely on other criteria and indicators to designate a model as having systemic risk.

On top of the first layer of obligations, providers of GPAI models with systemic risk are required to:

• Perform model evaluation with standardized protocols and tools;

• Assess and mitigate possible systemic risks at EU level;

• Report serious incidents and corrective measures to the European Commission and national authorities;

• Ensure an adequate level of cybersecurity protection.

2.4 Measures in support of innovation

The main measure foreseen in the Commission’s proposal is the mandatory establishment of at least one AI regulatory sandbox in each member state. A sandbox is a framework set up by a regulator that allows businesses, in particular start-ups, to conduct live experiments with their products or services in a controlled environment under the regulator's supervision.

The AI Act lays down detailed rules concerning the establishment and the functioning of AI regulatory sandboxes including rules on the further processing of personal data for developing certain AI systems with public utility.

2.5 Governance and sanctions

The AI Act establishes a very complex and hybrid governance framework, with implementation and enforcement powers split between the EU and national levels.

The European Commission will have a central role in the governance and implementation of the AI Act. In a nutshell, it will be responsible for enforcing the provisions relating to GPAI models, harmonizing the application of the AI Act across the EU, defining compliance with the AI Act and updating some critical aspects of the regulation. At national level, regulators will be responsible for enforcing all provisions relating to prohibited and high-risk AI practices.

a) EU level

The European Commission has established the AI Office to deal with the implementation and enforcement of the AI Act. The AI Office is a new agency established as part of the Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology.

The Commission will be inter alia responsible for:

• Enforcing all provisions relating to GPAI models: The Commission is given new powers for this purpose: to request documents and information; to engage in a structured dialogue; to carry out assessments; to require corrective measures; to order the withdrawal or recall of the model; to access GPAI models with systemic risks through APIs; etc.

• Adopting delegated acts on critical aspects of the AI Act, such as to amend the list of high-risk AI systems in Annex III or to amend the conditions for the self-assessment of high-risk;

• Issuing guidelines and elaborating codes of conduct on the practical implementation of the AI Act.

The Commission will be supported by three advisory bodies

• The European AI Board (the “Board”): composed of one representative per member state, with the Commission and the European Data Protection Supervisor joining as observers. The Board will act as a cooperation platform for national authorities in cross-border cases and will also be tasked with issuing opinions on soft law tools, such as guidelines and codes of conduct;

• The Advisory Forum (the “Forum”): composed of a balanced selection of experts from the industry, civil society and academia, along with representatives from the EU Cybersecurity Agency (ENISA) and the main EU standardization bodies;

• The Scientific Panel of Independent Experts (the “Panel”): composed of independent experts selected by the Commission. These experts will advise and support the Commission in the implementation of the AI Act, in particular with regards to GPAI. They will also support the work of national authorities at their request.

b) National level

Member states will have to designate an independent regulatory authority acting as a market surveillance authority responsible for the AI Act’s application at national level.

This market surveillance authority must be designated pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2019/1020, which frames market surveillance and product compliance in the EU for a wide range of products. This regulation gives significant enforcement powers to the national authorities, such as the power to conduct checks on products, request and obtain access to any information related to the product, request corrective actions or impose sanctions. Pursuant to the AI Act, national market surveillance authority will receive extra powers, such as a power to request access to the source code or to evaluate the high-risk self-assessment.

The AI Act also provides for the involvement of authorities in charge of fundamental rights and sectoral regulators in areas falling within their own fields of competence, such as financial regulators and data protection authorities whichever is higher.

• Non-compliance with other provisions: administrative fines of up to €15,000,000 or up to 3% of the total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher.

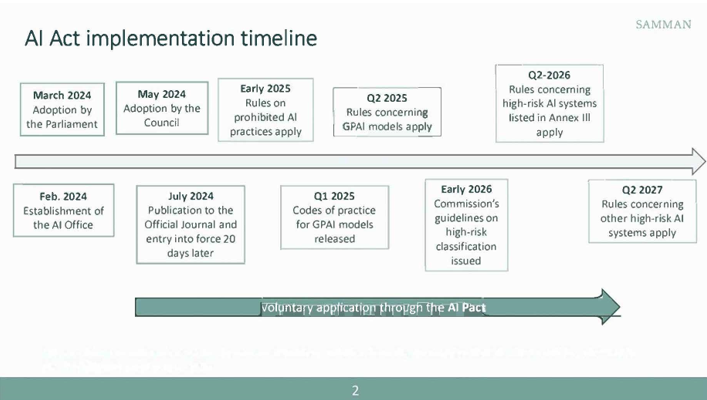

2.6 Implementation timeline

The AI Act was published in the EU Official Journal on 12 July 2024. It will enter into force 20 days after the publication and will be applied gradually:

• Rules on prohibited AI practices will apply 6 months after its entry into force (early 2025);

• Codes of practice for GPAI models should be issued, at the latest, by the Commission 9 months after its entry into force (Q1 2025);

• Rules concerning GPAI models will apply 12 months after its entry into force (mid-2025), which is also the deadline for the designation of national market surveillance authorities and the issuance of some guidelines on high-risk AI systems by the Commission;

• The Commission will have to issue guidelines on the classification of high-risk AI systems at the latest 18 months after its entry into force (early 2026);

• Rules concerning high-risk AI systems listed in Annex III will apply 24 months after its entry into force (mid-2026);

• Rules concerning other high-risk AI systems will apply 36 months after its entry into force (mid- 2027).

Finally, member states will have to designate at least one notifying authority, responsible for setting up and carrying out the necessary procedures for the designation and notification of conformity assessment bodies.

c) Financial penalties

On top of being able to request corrective actions, national authorities and the Commission will be able to impose fines, the amount of which will depend on the nature of the infringements: Non-compliance with prohibited AI practices: administrative fines of up to €35,000,000 or up to 7% of the total worldwide annual turnover,

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :