Institutions

Eric Maurice

-

Available versions :

EN

Eric Maurice

The French Presidency of the Council of the European Union began on 1 January in a context of post-Covid-19 recovery and the development of the dual climate and digital transition, and ends on 30 June in an environment shaken by the war in Ukraine.

In the space of a few weeks, the EU-27 have imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia, broken the taboo regarding financing the war, they decided to change their energy supplies and opened the door to further enlargement. They also are having to accommodate several million people fleeing war, deal with the highest inflation in decades and anticipate a global food crisis.

Under the motto "recovery, power, belonging", the French presidency of the Council, commonly referred to as the FPEU[1], has had to take the new situation in its diplomatic, political and economic dimensions into consideration. Whilst, according to the institutional scheme of things, the main orientations of the European Union's response have been decided by the European Council, and the measures taken have been prepared by the Commission, the role of the FPEU has been to coordinate the adoption and implementation of these measures, and to maintain the unity of the Member States.

This diplomatic and technical undertaking is what typifies a rotating Council Presidency. In the long-term work of European institutions, it organises the work of the Member States and the legislative process with the Parliament. Prepared in advance, it represents continuity in the projects that will be taken up by the next presidency, by following a programme prepared in coordination with its partners. In times of crisis such as those that Europe is currently experiencing, presiding over the Council means striking a balance between priorities defined in advance and the urgencies of the moment. An assessment of the FPEU must therefore be drawn on both levels, that of the processes and that of the events.

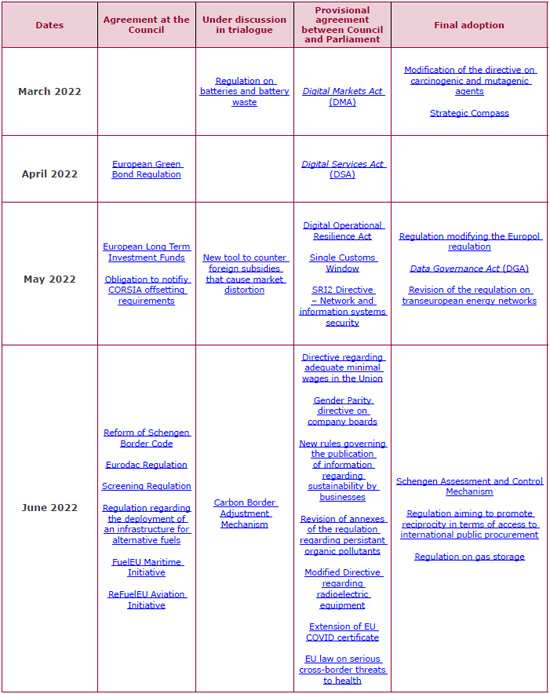

The FPEU in its strict institutional sense, i.e. the temporary chairing of meetings of ministers and their preparatory bodies, establishes goals in terms of legislative texts to be concluded or taken forward. As part of the broader ambition of building a sovereign Europe that defends its model of society, these objectives have largely been achieved.

Digital

The first of these was the regulation of digital platforms through two major texts presented by the Commission at the end of 2020: the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and the Digital Services Act (DSA).

After the Council and the Parliament each adopted their position at the end of 2021 on the DMA, France was able to conclude on 24 March an agreement between the two institutions. The final text, which has yet to be formally adopted by the co-legislators, provides for tougher regulation of the major digital platforms considered as "gatekeepers". The gatekeepers, under penalty of fines of up to 10% of their global turnover, will have to guarantee the interoperability of messaging systems and the protection of personal data, refrain from installing default software and pass on marketing or advertising data to vendors using their platform. The thresholds used to define gatekeepers are an annual turnover of at least €7.5 billion in the EU or a stock market valuation of at least €75 billion, as well as at least 45 million monthly end-users and at least 10,000 business users established in the EU.

On 23 April the Council and the Parliament also came to agreement over the DSA, designed to protect consumers from illegal and harmful content, and considered a more difficult project to conclude. The text, which will apply to sites with more than 45 million monthly active users in the EU, provides for the rapid removal of illegal content, products and services, greater transparency of algorithms, a ban on advertising targeted at minors and user profiling, as well as measures against cyber-violence or misinformation. The DSA will also oblige stakeholders to analyse annually the systemic social risks they may pose and to introduce risk reduction analysis.

Social

During its presidency, France aimed to "continue strengthening the social Europe", with the directive on adequate minimum wages proposed by the Commission in October 2020. After eight rounds of negotiations the Council and Parliament came to an agreement on 7 June. Minimum wages will be defined according to clear common criteria, to ensure a decent standard of living, taking into account the socio-economic conditions of each Member State: they will have to be reviewed at least every two years, and involve the social partners. The indicative level retained is 60% of the gross median wage and 50% of the gross average wage. Collective bargaining will have to be encouraged so as to cover at least 80% of employees. The directive is to be definitively adopted by the Parliament and the Council after the summer.

France also wanted to "advance" discussions concerning the draft directive on gender balance in boards of directors, which has been blocked for 5 years due to opposition from several Member States on the grounds of the subsidiarity principle. Since the new German government decided to lift its objection, an agreement was reached between Member States on 14 March, then with Parliament on 8 June. It requires listed companies to appoint at least 40% non-executive directors or 33% executive and non-executive directors of the under-represented gender to their boards by 2026. Its final adoption is expected before the end of the year.

However, the FPEU has not been able to start negotiations with the Parliament on the directive on transparency of remuneration, because MEPs only adopted their position in April. Regarding the regulation of the status of platform workers proposed by the Commission in December 2021, France undertook the assessment of the text from a technical point of view and put forward a first clarifying compromise, which will serve as a basis for discussions under the next Presidency.

Climate

As a central part of the EU's long-term strategy, the climate transition has been an important element of the FPEU agenda, via the Fit for 55 package, presented by the Commission in July 2021 to try to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990.

One element of this package was of particular importance to France: the proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which would, according to Emmanuel Macron, "reconcile industrial competitiveness with climate ambition" by taxing certain high-carbon imports as an incentive for foreign industries to reduce their carbon footprint and thereby protect European industries, which must comply with the EU's climate targets, from distorted competition.

Despite strong differences between Member States, the Council agreed on a general approach on 15 March on the basis of a compromise proposed by France. However, the compromise leaves out two related issues that are necessary for the adoption of the CBAM and need to be addressed at a later stage: the deadline for the total phasing out of free allowances under the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) allocated to industrial sectors covered by the CBAM to maintain their competitiveness; and the use of carbon tax revenues, which the Commission proposes to direct 75% towards the of the Union and which some Member States would like to see nationally. On 22 June, the European Parliament voted in favour of widening the scope and speeding up the CBAM in order to prevent carbon leakage and boost climate ambition.

The other projects in the climate package, still pending as the end of the FPEU approaches, including the reform of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and its extension to transport and buildings, the social climate fund and the ban on internal combustion engines in 2035, are all expected to be submitted to the Environment Ministers on 28 June. If an agreement is reached, negotiations might start on these issues following a vote by MEPs on 22 June (SEQE, Social Funds).

Migration and Asylum

At the start of the FPEU, the French government wanted to find "solutions to the most urgent problems" in terms of asylum, migration and the functioning of the Schengen area of free movement. The main aim was to break the deadlock in the discussions over the migration pact presented by the Commission in 2020, and to introduce the "political steering" of Schengen similar to that which exists for the euro zone.

Two texts were important to achieve this last objective. The first, the revision of the Schengen evaluation and control mechanism, was adopted on 10 June after an agreement between States in March and the consultation of Parliament in April. It introduces a more strategic focus, simplified, accelerated procedures, and strengthens the role of the Council by allowing it to adopt recommendations "in cases of serious non-compliance" by a Member State.

The second, the revision of the Schengen Code put forward by the Commission in December 2021 was the focus of an agreement 10 June between Member States on a general approach, and is still awaiting the Parliament's position. The draft includes new tools to combat the instrumentalisation of migration flows by third states or non-state actors, as well as a new legal framework for external border measures in the event of health crises. It would also allow Member States to extend internal border controls beyond the current limit of two and a half years, and would facilitate controls in the border regions of Member States to deter the movement of irregular migrants. The political steering sought by France has also resulted in the creation of a "Schengen Council" which met twice in March and June to discuss, among the 26 Schengen States[2] the major issues at stake, independently of the discussions regarding the texts.

The FPEU also succeeded in taking forward discussions on asylum and migration. On 10 June after a political agreement between ministers, the Council adopted its negotiating mandates on the Eurodac and Migrant Screening Regulations. The first text, which concerns the migrant fingerprint database, aims to improve the fight to counter irregular border movements and to facilitate the return of illegal immigrants to their country. The second text provides for the strengthening of external border controls and the "rapid referral of screened persons to the appropriate procedure". Negotiations with the Parliament can begin once it has adopted its position.

In addition, on 22 June, 21 Member States committed "to implement a voluntary, simple, predictable solidarity mechanism" to assist Member States facing large-scale arrivals of migrants in the Mediterranean and on the Western Atlantic route. This commitment overcomes one of the major obstacles to the development of a comprehensive long-term migration policy, the opposition of some Member States to any binding mechanism for the relocation of asylum seekers.

Security and Defence

The Strategic Compass, a major element of France's ambition to develop the European Union's strategic autonomy and capabilities, as well as a common strategic culture, was adopted during the European Council of March exactly one month after the start of the invasion of Ukraine. A first draft was made in autumn 2021. During the meeting of Ministers of Defence in Brest on 13 January, France initiated further more in-depth work on the subject. The war forced the European External Action Service and the FPEU to rework the document, which was more focused on the Russian threat, more ambitious in its objectives and the means to achieve them, and ultimately called for a "quantum leap" to "increase our capacity and readiness to act, strengthen our resilience and ensure solidarity and mutual assistance". Divided into four pillars - acting, investing, collaborating and securing - the Compass sets out the European Union's security and defence priorities for the coming decade and lists the projects to be carried out to meet them. The most visible measure is the creation of a "rapid deployment capability" of 5,000 troops by 2025. The Compass also provides for the strengthening of the Union's civilian and military missions, the establishment of common space and cyber defence policies, and investments in operational capabilities and cutting-edge technologies, which are not quantified. As holder of the Council Presidency, France has begun implementing the strategy, particularly in the area of military mobility and action against hybrid threats.

This work was complemented in parallel by the impetus given by EU leaders at their meeting in Versailles 10-11 March to address strategic shortfalls, boost defence industry investment and capabilities. Following an analysis of the EU's defence investment gaps by the Commission and the European Defence Agency (EDA), the European Commission decided to launch an EU-wide defence investment programme, the European Council of 30 and 31 May asked for "a mapping" of defence manufacturing capabilities, develop measures to support the sector and facilitate joint procurement to strengthen stocks.

Confronting the war

All these agreements and decisions, supplemented by numerous Council policy documents, such as the conclusions and recommendations, made up in the main the programme of the semester as it had been planned. But the FPEU also had to manage the EU's response to the Russian-led war in Ukraine on 24 February and its consequences. This activity has included a high number of ambassadorial meetings - 71, compared to 51 during the Portuguese Presidency in 2021 and 53 during the Croatian Presidency in 2020[3]. Several extraordinary meetings of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Energy and Interior were also held.

The most important work in this context was the adoption of the six sanctions package against Russia and Belarus between 21 February, when Russia recognised the breakaway regions of Ukraine, and 3 June. The EU sanctions now target 1,158 individuals and 98 entities involved in the war and the violation of Ukraine's sovereignty. They mainly include the exclusion of Russian and Belarusian banks from the SWIFT financial messaging system, a ban on financial exchanges with the Central Bank of Russia, trade restrictions, as well as embargoes on Russian coal and oil.

The FPEU has also helped to organise the reception of more than 5 million Ukrainian refugees in the European Union, giving support to Ukraine in various shapes and forms. The Council thus introduced temporary protection for a year for people fleeing the war, which allowed for the re-orientation of cohesion funds to help refugees to a total of 17 billion €, approving the release of 3.5 billion more € with the same goal in mind.

Through a series of Council decisions, the European Union has broken the taboo surrounding the financing of war, since it has triggered the peace facility on four occasions to a total of 2 billion €, to compensate Member States for the supply of arms, protective equipment and fuel for the armed forces to Ukraine. Together with the Parliament, the Council also approved the temporary liberalisation of trade with Ukraine, and adopted new rules allowing Eurojust to safeguard evidence of war crimes.

After an agreement between the Member States on 10 May, the Council and Parliament came to an agreement, on 19 May concerning the obligation for Member States to fill their gas storage facilities to at least 80% before the next winter, so as to ensure security of supply as part of the move away from dependence on Russian gas. The text was definitely adopted on 27 June.

In the face of the multiple challenges created by the war in Ukraine, it was in its role as a preparatory body for the meetings of another institution, the European Council, that the FPEU played a central role in strategic decisions. The declaration adopted at the extraordinary summit of heads of state and government in Versailles on 10 and 11 March, was drawn up first and foremost at the Elysée Palace and bears the mark that France would like to leave on the European Union. The 27 maintained that they had "decided to take greater responsibility for our security and to take decisive new steps to build our European sovereignty, reduce our dependence and develop a new growth and investment model for 2030".

The declaration thus sets out the three pillars of the European Union's repositioning in the face of war: strengthening defence capabilities, reducing energy dependence and building a more solid economic base. It also stresses the need to reduce strategic dependence, in the fields of digital and technology, raw materials, health and food. The European Councils of 24-25 March and 30-31 May clarified and complemented this strategy, but no fundamental decisions were taken on the exit from Russian gas nor regarding a concrete plan to strengthen the defence industry.

Challenged ambition

From this point of view, the Versailles meeting was the moment in the FPEU when the French ambition to shape the European Union in the long term was most evident and most disrupted by the shock of war.

At the start of its six-month European mandate, France added a strong political and programmatic dimension to the purely institutional aspect of a Council Presidency. "If I had to sum up in one sentence the goal of this Presidency from 1 January to 30 June, I would say that we need to move from being a Europe of cooperation inside of our borders to a powerful Europe in the world, fully sovereign, free to make its choices and master of its destiny," explained French President Emmanuel Macron on 9 December when presenting the priorities of the FPEU.

The Versailles summit on 10 and 11 March was supposed to launch reflection on a "new European model of growth and investment", which would have addressed the issues of industrial cooperation, the financing of innovation and social policies to achieve the dual transition to climate change and digital technology. This reflection would have coincided with the discussions on the reform of the governance of the euro zone and, more specifically, of the Stability and Growth Pact. The Versailles declaration only contains a draft discussion because the management of the economic consequences of the war has interrupted debate with regard to the euro zone. These issues will be brought back to the table of European leaders anyway.

In a way the idea of European strategic autonomy was validated by the war and enshrined in the Versailles Declaration, although paradoxically it has been thwarted in practice by events, since some member states, particularly in the East, consider membership of NATO and the American security guarantee to be essential, and view the concept of autonomy with suspicion, and as a potential weakening of NATO. The balance sought by Emmanuel Macron in the Ukrainian crisis and his project for a "European political community" unveiled on 9 May will have reinforced this mistrust among some of its partners.

The ambivalence of these states regarding strategic issues and their announced intention to reconstitute stocks and operational capabilities with American equipment leaves some uncertainty as to whether the guidelines for investment and cooperation in the European defence industry will actually be implemented as France would like it.

However, France's capacity to work alongside and with its main partners Germany and Italy, was demonstrated in Kyiv 16 June, when Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz, Mario Draghi and Romanian President Klaus Iohannis gave their support to Ukraine's application to join the European Union. The gesture, followed by a COREPER meeting and a General Affairs Council, enabled the guarantee of a unanimous decision at the European Council of 23 and 24 June to grant candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova, while preparing the discussion on how this is to be achieved.

For France, the FPEU has been a moment of achievement of many concrete objectives, as well as a demonstration of the effectiveness of its diplomatic and political apparatus in Brussels and Paris, while at the same time putting some of the stated long-term ambitions for the European Union in the background. However, the reflection on the future of the Union has only just begun. Despite the consequences of the war in Ukraine, France, which can claim a very positive presidency with concrete results, will continue to place itself at the heart of these upcoming debates.

[1] For the French Presidency of the European Union

[2] All members of the European Union (except Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Ireland and Romania), as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

[3] Comparison with an equivalent six-month period, as the presidencies from 1 July to 31 December are lightened by the summer holidays and the end-of-year celebrations.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :