Multilateralism

Alan Hervé

-

Available versions :

EN

Alan Hervé

The carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), the fight to prevent illegal foreign subsidies, the ban on trade in deforestation products, the due diligence obligation imposed on European companies, the anti-coercion regulation, the reciprocity instrument in public procurement, the foreign investment screening regulation, not to mention the set of exceptional trade measures implemented in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine; there is a long list of decisions adopted and under discussion that mark the European Union's determination to decide alone on the regulation of trade between itself and the rest of the world. This European "neo-unilateralism" is certainly based on a logic that is not entirely new - the defence of the Union's interests through trade policy or trade regulation instruments - but it also presents singular features and reflects political choices that prevail, more than in the past, over strict mercantile considerations. It is a vehicle for promoting the European Union's strategic autonomy in a multilateral system that is in the process of collapsing and an international order that has been hit by crises.

The collapse of the multilateral system, the collapse of free trade

To understand European neo-unilateralism, it is important to look back at how the EU has conducted its trade policy to date. For a long time, the EU has repeatedly insisted on the need for an 'open and rules-based' trading system, defined at the WTO or, in a complementary way, in its free trade agreements. Through schismogenesis[1], it has sought to distance itself from other powers, first and foremost the United States, which are suspected of wanting to impose decisions on the rest of the world that are in their own interests, bypassing common rules if necessary.

European support for multilateralism has even taken on essentialist characteristics, in that it reflects the way in which the European Union has built itself internally, through the construction of predictable and liberal rules and procedures. The creation of the WTO in 1995, the acme of triumphant multilateralism, confirmed this post-Westphalian reading of international relations, within which the organisation of trade obeyed a liberal and cosmopolitan order[2]. In a rare move[3], The European Union was recognised as a full member of this international organisation, which was built on a vast set of trade agreements covering old and new aspects of trade and whose respect would henceforth be guaranteed by an effective, 'jurisdictional' dispute settlement mechanism, the jewel in the crown of this new ensemble. The success of the WTO was further reinforced, both economically and ideologically, by the entry into the organisation of the former communist bloc countries: People's China (2001) and, a few years later, Vietnam (2007), Ukraine (2008), and Russia (2012). The universalisation of the WTO represented the course of history.

This narrative has failed. In reality, the multilateral system has been slowly eroded, starting in the late 1990s with the failure of the Seattle conference[4]. Despite the adoption of an ambitious work programme in Doha at the end of 2001, negotiators were unable to agree, as they had done in the 1990s, on a much-needed adaptation of the trade organisation's rules to the rapidly changing international economic system, the nature of trade and value chains. Any ambition to reform the organisation and its governance failed, and the WTO's political bodies were quickly trapped by the rule of consensus, their division and their inability to think of new common ground[5]. However, there is no shortage of topics of interest, from the coexistence of liberal economies with state capitalism models in the international trade system to the need to integrate social, environmental and climate issues into the development of trade rules.

As the years have passed, the original consensus that founded the multilateral pact has continued to crumble. The WTO continues to function, as illustrated by the lengthy process of appointing a new Director General after the de facto abandonment of the Doha Round[6]. But despite occasional progress in negotiations, the WTO is a club of diplomats whose disagreements have become deep, disputes intractable and exchanges acrimonious. The WTO's dispute resolution system is permanently undermined by the paralysis of its Appellate Body[7]. The disappearance of the arbiter of world trade, whose primary purpose was to prevent trade disputes from leading to economic wars, is now a matter of concern only to a small circle of specialists, while the highest political authorities remain indifferent. The WTO simply suffers the shocks of geopolitical rivalries and tensions. For several years now, we have seen a proliferation of exceptions justified by emergency and national security imperatives[8]. Multilateral rules are now marginalised in a growing number of inter-state relations, due to a rise in conflicts. They are thus regularly abused in the context of the Sino-American trade war. Several countries in the Western camp - including Canada, the USA, the European Union and the UK - have just announced their decision to suspend the application of most-favoured-nation status[9] with regarding to Russia.

The European Union is not immune to the growing instability that characterises the current system of structuring world trade. The uncertainty generated by Brexit is still far from being resolved, despite the conclusion in spring 2021 of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. The propensity of the British to effectively respect their commitments - starting with the Northern Ireland protocol - remains very uncertain, given the current government's preference for a transactional approach and power struggles. The Covid-19 health crisis has confirmed to Europe, which is poor in natural resources, the risks of weakening the entire value chain of its companies, particularly when export restrictions proliferate. In addition, there is now an economic and trade war with Russia, which is rich in raw materials and on which it is dependent for energy.

In the course of a few years, Europeans have entered a new era, typified by the possible sudden emergence of security considerations - linked to military events, health and climate crises - which may at any moment challenge the usual rules of international trade. In this more violent, more conflictual world, where respect for the law is giving way to a rationale of power, it is easy to understand the need for the European Union to thoroughly rethink the tools and instruments of its external action, in particular those of its trade policy.

The European Union has already acknowledged the need to secure trade through rules defined outside the WTO framework. For more than two decades, it has pursued an ambitious strategy of negotiating trade agreements which, far from being confined to promoting trade liberalisation, constitute objects of European regulation of international trade[10]. Although this method often helps to overcome the limitations of the multilateral system, it does have its limits, as the European Union does not yet have global trade agreements with major economic and political players, such as the United States, India, Brazil, Russia and China. Moreover, despite its commercial weight, the EU cannot always impose its wishes on its conventional partners in negotiations and must make certain compromises[11].

Unilateralism as a traditional tool to promote the EU's interests on the international scene

The use of unilateral measures as an instrument to regulate trade with the outside world is ancient, concomitant with the structuring of states in their modern form[12]. Unilateral measures differ from bi- or multilateral trade agreements because of the way they are formed, which does not require the consent of third parties and depends exclusively on domestic political choices. For this reason, unilateral measures are seen as both manifestations of sovereignty and protectionism. However, it is usual for the adoption of unilateral measures to be accompanied by a prior dialogue with the actors affected by the measure, in particular the targeted companies or third states. Moreover, unilateral measures are very often part of the implementation of trade agreements, which frame their use.

Basing itself on its competence in terms of trade[13], the European Union has, since its inception, used its capacity to adopt unilateral measures. This is the case with tariffs applied to imports from third countries, in accordance with the commitments formulated in the GATT schedules of concessions and, later, in free trade agreements. These measures may be adopted to defend certain trade interests, under the policy space recognised by international trade rules. This is particularly the case for trade defence measures, which in this case take the form of additional customs duties, in response to dumping practices or illegal subsidies[14]. Similar schemes allow for export restrictions[15] or the use of trade sanctions authorised by the WTO following a dispute settlement procedure.

However, certain unilateral European measures have a disruptive purpose, intended, depending on the case, to fill gaps in the agreements or to challenge the rules of trade. This is a long-standing phenomenon. In the early 1970s, the European Community chose to create the first system of tariff preferences granted by a GATT member to developing countries[16]. This decision, however, called into question the logic of non-discrimination underpinned by the most favoured nation status, a cardinal rule of the GATT, and then of the WTO. This European mechanism was made compatible with the rules of the organisation by means of temporary and then permanent derogations, in virtue of a empowerment clause adopted in 1979. The choice of members of the multilateral system to break with legality can also serve a long-term strategy, aimed at forcing third countries to negotiate new rules that take into account the concerns of the country that decides, initially on its own, to transgress the common disciplines. In the 1980s, the European Union and the United States unilaterally sanctioned GATT members that refused to respect their own intellectual property standards. This strategy of "aggressive unilateralism" paid off, as it forced the targeted countries to agree to the inclusion of the future IP agreement[17].

European neo-unilateralism as a response to the increasing challenges to the EU's trade policy

By "neo-unilateralism" we mean the proliferation of recent unilateral measures adopted by the European Union that are likely to apply to international trade[18]. This phenomenon is the direct translation of a European discourse, which defends the strategic autonomy of the European Union on the international scene. To illustrate this, the starting point is the unilateral measures adopted or proposed in December 2019 with the appointment of the current European Commission, whose President, on taking office, described it as 'geopolitical'. In addition to the traditional unilateral measures[19], we have chosen to distinguish two categories of unilateral measures that affect trade between Europe and the rest of the world:

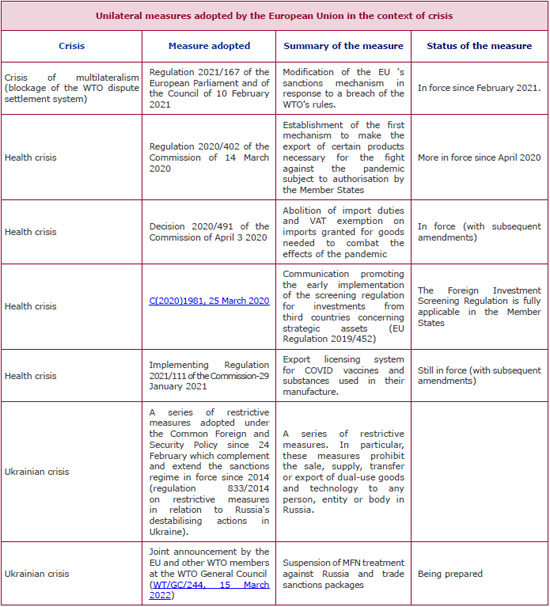

1° Unilateral measures adopted by the European Union in response to a crisis context

The EU's trade policy has faced an increasing number of crises that have required rapid and appropriate responses. This was the case with the case arising from the paralysis of the WTO dispute settlement system, due to the American veto on any new designation of an Appellate Body member. In addition to its proposals for reform of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism[20], the European Union deemed it necessary to review its 2014[21] which establishes the Commission's power to adopt trade sanctions against other WTO members. Until now, European sanctions could only be imposed after the WTO had given its authorisation following a multilateral procedure. The revised version, in force since February 2021, now offers the possibility of introducing sanctions without prior authorisation from the WTO, when the European Union is faced with obstruction of the dispute settlement procedure by an opposing country[22]. In other words, the text encourages the use of unilateral measures to overcome the possible paralysis of the WTO dispute settlement system[23]. This is a textbook case of the substitution of unilateral logic for multilateral procedures, due to their inadequacy.

Mention should also be made of the set of trade policy instruments deployed during the Covid-19 pandemic. In March 2020, the Commission, under pressure from the measures taken by its Member States, decided to introduce a system of restrictions on exports of products related to the fight against the pandemic[24] at the same time as it temporarily lowered tariffs to facilitate imports. The Commission would encourage Member States to anticipate the entry into force of the new EU legislation on screening foreign investment[25], to prevent non-European companies from taking advantage of the crisis to take over European companies operating in strategic sectors[26]. In January 2021, faced with the emergence of vaccine protectionism, the Commission urgently deployed an administrative authorisation regarding a mechanism on exports of products necessary for the manufacture of vaccines[27].

The measures adopted in the context of the invasion of Ukraine confirm this capacity to react quickly. In 2014, shortly after the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of the Donbass, the European Union decided to prohibit exports of certain categories of goods to Russia, in particular those with dual use (civilian and military) and to exclude all imports from the annexed territories. These trade measures were considerably tightened at the start of the invasion of Ukraine[28]. The European Union has just announced, in line with national security exceptions, that it wants to bring to terminate Russia's status as most favoured nation, which means that it no longer considers this state to be a 'normal' WTO member in practice. It remains to be seen whether, on this basis, the European Union will, in the coming weeks, be willing and able to go further by deciding, in particular, to prohibit imports of hydrocarbons from this aggressor state.

2° New unilateral legislation as part of a project to rewrite the rules of international trade

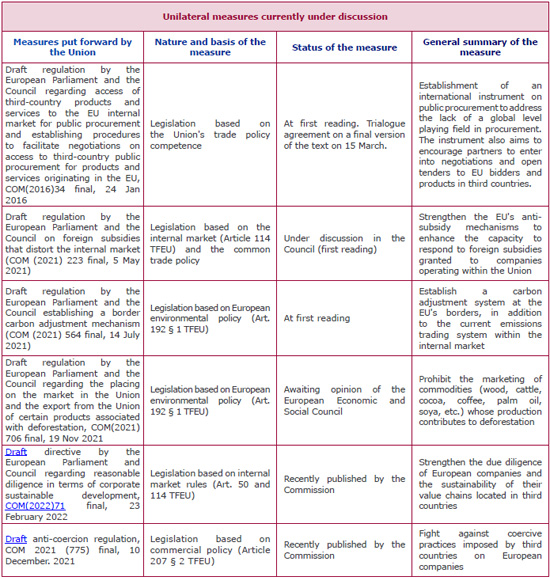

Six proposals for legislation by the European Commission since 2019 are at issue[29]. It is this last manifestation of unilateralism which is the most instructive in that it translates into action - still under discussion for the most part - the discourse on European autonomy and sovereignty, applied to the regulation of international trade[30]. These six draft laws, five regulations and one directive[31], are part of an accepted European strategy to use the market and its normative power to regulate trade in a context of legal vacuum within the Union, but also internationally.

After years of discussion starting in 2012 on France's request, the agreement on the creation of a new international instrument for public procurement, supplementing European internal legislation on public procurement, is also justified by the fact that the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement does not, as it stands, allow European companies sufficient access to tenders issued in third countries, in terms comparable to the access to European public contracts enjoyed by foreign companies, in particular Chinese ones[32]. The Commission also hopes to have at its disposal a tool to counter foreign subsidies from which companies operating in the internal market benefit, so as to close the loopholes left by the common market rules on state aid, but also by the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures.

The carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is currently being discussed, aims to fill the gaps in the international rules on combating climate change, as the Paris Agreement continues to have little binding force on the States Parties. The European proposal extends the logic of the EU's internal emissions trading mechanism by targeting a list of products that are particularly CO2 emitting in their manufacturing and production process (cement, steel, fertilisers).

The same applies to the draft regulation designed to counter deforestation, which closes loopholes in international rules by banning certain imports (coffee, cocoa or palm oil). The draft anti-coercion regulations and a directive on corporate due diligence are intended to fill a gap left by multilateral trade rules, which do not allow for an effective fight against coercive measures imposed by foreign states on European companies (economic and political pressure, restrictions on the right to trade or invest) or, conversely, are uninterested in the conditions under which multinational companies, including European ones, organise their production and their value chain without taking into account respect for human rights or social and environmental standards.

The other striking feature of these measures is the attempt to apply the objectives and values of the European Union to international trade. This is particularly the case in the field of the environment and, more generally, the fight against climate change, echoing the objectives assigned to the Union's action on the international scene under the treaties[33] and increasing political pressure on these issues. Trade policy is thus a vehicle for promoting other EU policies, including in areas where competences are still shared with the Member States, especially when European external action in these areas has had only mixed results (weak international governance in the social field, timid progress on climate change rules).

The emphasis on non-market considerations in trade policy is not exclusive of an underlying economic motivation, which in practice is of prime importance to the legislator, namely the defence of a level playing field, i.e. fair conditions of competition between the European Union and its partners, and which relates to the competitiveness of European companies at international level.

The European Union cannot continue to impose ambitious regulatory conditions on its own companies, whether it be carbon quotas, rules governing the use of chemicals and pesticides or the prohibition of subsidies, when foreign competition is benefiting at the same time from a much more conciliatory normative and fiscal framework in third countries and from the increasing opening up of access to the European market, unless it encourages further relocation and a loss of industrial autonomy. For a long time, this tension has contributed to reducing the ambition of European legislation. This is evidenced, for example, by the free allocations of carbon quotas companies producing in Europe and facing international competition, in line with the EU Emissions Trading Scheme[34]. Now, the trend is to reverse this approach, with the European Commission proposing ambitious texts, including at the domestic level, but with extraterritorial effects, in order to guarantee fair trade[35].

The future of this neo-unilateralism raises questions: is it a passing fad or a profound evolution of the European Union's action on the international scene, in line with the affirmation of its strategic autonomy?

The answer will depend primarily on the real will of the institutions, in particular the European Parliament and the Council, to adopt the legislation proposed by the Commission without altering its content too much, or even to strengthen its scope[36]. Lobbying by third countries and economic sectors is likely to influence the choices made. It seems that the political context lends itself to this, but economic crises can have the effect of forcing short-term economic choices, particularly in a context of security tensions. The other major unknown is obviously the reaction of third countries to this series of unilateral measures, which may be perceived as a forced attempt to impose on the rest of the world the environmental, health, social and even fiscal policy choices made within the Union[37]. The European Union can hope that its initiatives will be taken up and influence other legislators, in accordance with the so-called Brussels effect theorised by Anu Bradford[38], and which can already be observed in the data protection sector[39]. But it is also likely that other members of the trading system will seek to challenge these new rules at the WTO and that European legislation will be the source of major trade disputes for several years to come and, potentially, of European condemnations followed by threats of economic retaliation. The surest way to avoid this worst-case scenario would be for European unilateralism, which is based on a series of concerns that are not specific to the European Union, to contribute to a revival of multilateralism.

ANNEX 1

ANNEX 2

[1] Process of differentiation between societies, which constitutes a form of identity marker. On this notion, see D. Graeber & D. Wengrow, In the Beginning was... A New History of Humanity, ed. LLL, 2021.

[2] V. E.-U. Petersmann, "The Future of the WTO: From Authoritarian 'Mercantilism' to Multilevel Governance for the Benefit of Citizens?", Asian Journal of WTO & International Health Law and Policy, 2011, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 45-80

[3] It is worth recalling that the European Union, despite the existence of the Euro and the progress made in banking and financial integration, does not enjoy membership of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. The same is true of the UN and the institutions that derive from it, where it generally has only observer status.

[4] This WTO ministerial conference, which was supposed to result in a new multilateral negotiation agenda, crystallised oppositions between member countries, in particular the divide between the countries of the North (led by the United States and Europe) and the countries of the South, led by the emerging powers (Brazil, India, South Africa). Violent demonstrations took place on the sidelines of this event, marking the beginning of anti-globalisation protests.

[5] Conference by Pascal. Lamy, then EU Trade Commissioner, 15 September 2004.

[6] The selection process for the future WTO Director General began after Mr. Azevedo resigned in May 2020. It could only be completed in February 2021, after the departure of the Trump administration, which was blocking the consensus necessary for the nomination of Ms. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala

[7] The Appellate Body no longer has a single active member due to the blocking of its appointment system by the US, under a choice made during the Obama administration and subsequently confirmed by Donald Trump and Joe Biden. WTO panels continue to operate, but in practice it is sufficient for a party to appeal the findings of a report to block the dispute settlement process.

[8] This question of the legality of measures that are contrary to WTO rules but justified by national security imperatives has been at the heart of the dispute Russia - Transit Traffic. In April 2019, the panel in this dispute ruled in favour of Russia, and refused to assess the timeliness of "security exceptions" in the event of serious international tensions. The Trump administration justified the restrictions to imports of steel and aluminium, from 2018, on the basis of national security.

[9] This rule, which grants all WTO members the trade benefits that one member grants to another, has been the basic principle of the multilateral trading system since 1947. In addition, a series of trade sanctions adopted by these countries against Russia.

[10] A. Hervé, "The European Union and its model to regulate international trade relations", Robert Schuman Foundation, 14 April 2020.

[11] Assuming it really wants to, the EU is thus struggling to impose its social and environmental standards on third countries, which see this as a new form of protectionism.

[12] Regarding this idea, Denys-Sacha Robin. Les actes unilatéraux des États comme éléments de formation du droit international. Droit. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne - Paris I, 2018.

[13] This competence has existed since the Treaty of Rome. Article 3 TFEU recalls its exclusive nature, which means that the Member States can no longer intervene in this area. Article 207 TFEU defines its scope (trade agreements, customs tariffs, trade in services, commercial aspects of intellectual property, foreign direct investment).

[14] To this end, the EU has basic legislation that organises the procedures for implementing trade defence (e.g. Regulation 2016/1036 June 8 2016). In practice, it will be up to the Commission to take the decision by means of an implementing regulation.

[15] See articles XI and XIIi of the GATT and refer to the 1995 Basic Regulation and the measures adopted on its basis in the context of the health crisis.

[16] In 1971, the Community was the first GATT member to unilaterally recognise customs preferences for a wide range of products originating in developing countries. The European GSP is governed by the Regulation 978/2012 du 25 oct. 2012.

[17] Agreements on intellectual property rights which affect trade (ADPIC). V. J. N. Bagwhati and H. T. Patrick, Aggressive Unilateralism: Americas 301 Trade Policy and World Trading System, 1990, Michigan University Press; J. Gero and K. Lanna, Trade and Innovation: Unilateralism v. Multilateralism, 21 Can.-U.S. L.J. 81, (1995)

[18] While it is right to focus on measures based on the Union's trade competence, other measures that could significantly affect trade, such as the proposal for a border carbon adjustment mechanism, although based solely on the Union's environmental competence, should also be mentioned.

[19] This category includes trade defence measures, in particular anti-dumping or anti-subsidy measures, adopted by the Commission in accordance with EU legislation and WTO agreements. There has been no particular upsurge in this type of measure in recent years. See European Commission, statistics on trade defence 2021. Mention may also be made of the measures for implementing the Generalised System of Preferences.

[20] See Annex the Commission Communication of February 2021, An open, sustainable and reliable trade policy, COM(2021)66 final.

[21] Regulation 654/2014 of 15 May 2014 on the exercise of Union rights to apply and enforce international trade rules.

[22] This can be done by a WTO member appealing a panel report. Such a manoeuvre may be tempting if there is a risk of a penalty.

[23] The legislative revision also extends the possibility for the EU to use trade sanctions in the areas of services and intellectual property, which were previously only tariff-based

[24] Masks, hydroalcoholic gels or respirators. Regulation 2020/402 by the Commission 14 March 2020.

[25] Regulation 2019/452 establishing a framework for the screening of foreign investment in the European Union. This legislation was initially only to apply from October 2020.

[26] At the end of 2021, the Commission reported more than 260 cases notified by the Member States. See First Annual Report on Screening of Foreign Direct Investment, COM/2021/714 final, 23 Nov 2021.

[27] In November 2021, this mechanism was replaced by a more flexible surveillance system, extended for a period of 24 months.

[28] Decision (CFSP) 2022/327 by the Council on 25 February 2022. This decision was then extended to Belarus in early March.

[29] With the exception of the international instrument on public procurement, under discussion since 2016.

[30] The discourse on sovereignty also finds other fields of expression, for example in the digital sector with the proposals made in the Digital Market Act and the Digital Service Act.

[31] As a reminder, regulations are, from their entry into force, binding in their entirety and directly applicable at national level. As a two-tiered piece of legislation, the Directive requires national transposition measures that Member States are obliged to adopt.

[32] According to the OECD, in 2017, public procurement accounted for around 12% of GDP in OECD countries, with significant variations between countries. The market access potential is thus considerable.

[33] See article 21 of the Treaty on European Union.

[34] The so-called "free allowances" system, the possible lifting of which is being discussed in the context of the border carbon adjustment project.

[35] However, it is not a matter of imposing rules on producers located in third countries, which would run counter to the logic of sovereignty. However, foreign companies wishing to access the European market will have to modify their production processes and means, including when these take place outside the territory of the Union.

[36] Many people feel that the carbon adjustment system currently under discussion applies to narrow a range of products, and that the implementation deadlines envisaged (in particular that for the abolition of free allowances) fall far short of the needs imposed by the climate emergency.

[37] Although in the latter area it may be limited by the unanimity rule.

[38] A. Bradford, The Brussels Effect - How the European Union Rules The World, OUP, 2020.

[39] Thus, the adoption of the General Regulation on the protection of personal data (RGPD) has influenced the legislation of third countries, in particular those wishing to obtain an "adequacy decision" from the Union facilitating the transfer of data to their territories, conditional on compliance with European standards. The State of California has adopted a text that is partly inspired by European rules (California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), 3 November 2020).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :