Economic and Monetary Union

Nicolas Goetzmann

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas Goetzmann

On 23 January 2020, a few weeks before the Covid-19 pandemic began, Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank (ECB), announced that a "strategy review" would be held with the aim of evaluating the monetary policy conducted since May 2003, the date of the last "review". Faced with an inflation rate significantly below 2%, whereas its objective is "below but close to 2% over the medium term", the ECB had no choice but to carry out such a procedure.

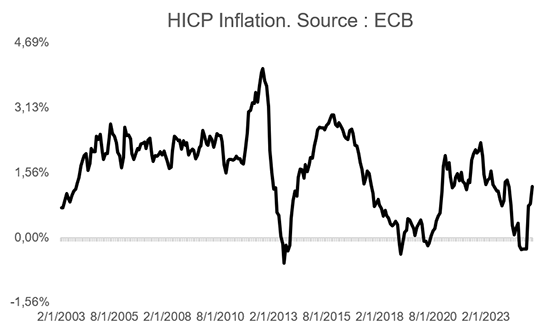

In a speech delivered[1] on 30 September 2020, Christine Lagarde declared: "Since 2003, when we last conducted a strategy review, the euro area and the world economy have undergone profound changes. The consensus that has governed monetary policy worldwide has been challenged on a number of fronts. Most importantly, the last decade has been defined by a persistent decline in inflation among advanced economies. In the euro area, annual inflation averaged 2.3% from 1999 to the eve of the great financial crisis in August 2008, but only 1.2% from then until the end of 2019. This environment poses fundamental questions for central banks. We need to thoroughly analyse the forces that are driving inflation dynamics today and consider whether and how we should adjust our policy strategy in response."

The aim of the Monetary Policy Strategy Review is therefore to determine the causes of the low inflation observed in recent years, but also to assess the means available to the ECB to counter this phenomenon. Indeed, the strategy review sets a fundamental question for the euro area. While the ECB's raison d'être is "price stability" and European monetary policy has embodied the fight against inflation since the drafting of the Maastricht Treaty, the concern about "too low inflation" seems paradoxical. Yet, while the general public sees the fight against inflation as synonymous with the protection of purchasing power, persistently low inflation in the euro area is a symptom of low growth, sub-optimal employment and under-investment. The ECB must react to such a phenomenon, just as the Federal Reserve (Fed) reacted to it by announcing, on 27 August 2020[2], the implementation of a new monetary policy strategy for the United States.

The euro area faces an unstable monetary framework

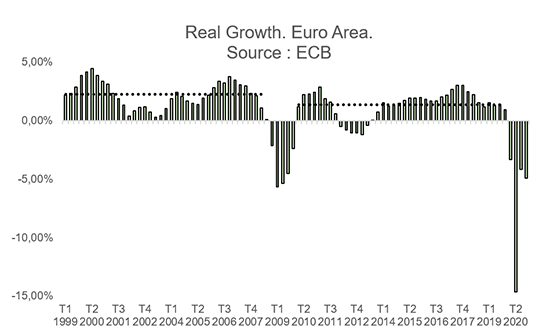

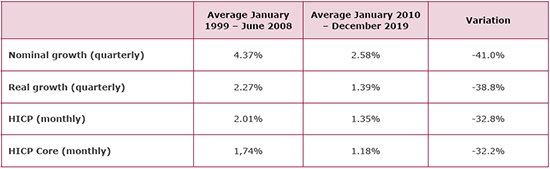

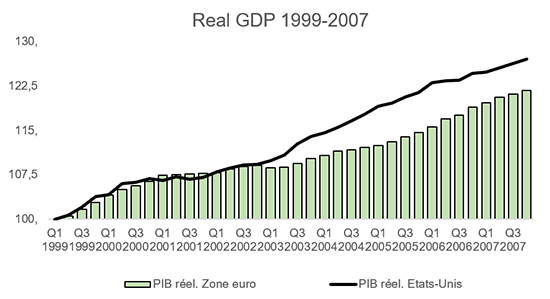

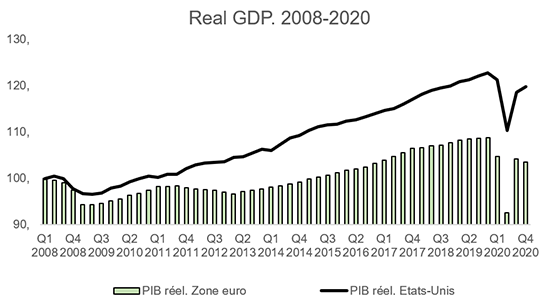

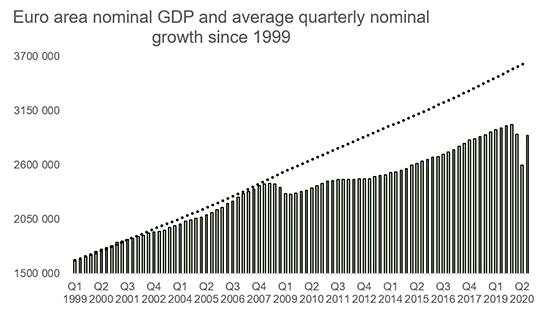

The financial crisis of 2008 marked a fracture in the development of the euro area. While its average quarterly growth lay at 2.27% between the first quarter of 1999 and the second quarter of 2008, it totalled only 1.39% between the first quarter of 2010 and the fourth quarter of 2019 (i.e. not during the crisis), i.e. a decrease of almost 40% (38.8%) between the two periods. The decline in average European growth was not gradual, but sudden, and the financial crisis of 2008 was the tipping point.

The nominal decrease in GDP has resulted in real effects in the economy

Taking into account nominal GDP growth (a gross measure of the economy, integrating real growth and inflation) within the euro area delivers a similar result. After an average nominal growth of 4.37% between 1999 and 2008, the euro area experienced only an average of 2.58% nominal growth between 2010 and 2019, a decrease of 41% - periods of crisis excluded. The decline in nominal growth for the euro area was evenly split between a 38.8% decline in real growth and a 32.8% decrease in inflation, according to the ECB's preferred HICP measure.

Lower growth and inflation prospects linked to ill adapted monetary policy responses

However, the decrease in inflation, like that in nominal growth, can be seen as the result of the ECB's action. Indeed, the objective of monetary policy is to ensure macroeconomic stability for the area under its responsibility, which can be measured by the evolution of inflation or, more broadly, by the stability of nominal growth. In a speech given on 24 October 2003, Ben Bernanke stated: "Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation[3]". According to this interpretation, the sharp decrease in the various nominal measures (nominal growth and inflation) should be understood as the result of an overly restrictive monetary policy on the part of the ECB. This decrease in nominal indicators has not been without effects on the "real" evolution of the economy. It appears that the nominal decrease observed in recent years has had a decisive impact on the level of real growth in the euro area.

After a first decade of satisfactory growth, the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis marked a point of fracture for European growth. While this phenomenon has been largely analysed from the point of view of structural causes, the concomitance of the decline in real growth with that of nominal indicators such as nominal growth and inflation demonstrates a problem whose cause is mainly of a monetary nature.

While the ECB's monetary policy was able to deliver a stable nominal trajectory during the first 9 years of the euro's existence, it has not been able to support the euro area economy at a sufficient level to regain its initial trajectory, thus suggesting that its strategy remains ill-suited to cope with a shock of the magnitude of the financial crisis. In this case, a comparison between the dynamics observed in the euro area and those experienced in the United States during the same period can provide another framework for analysis.

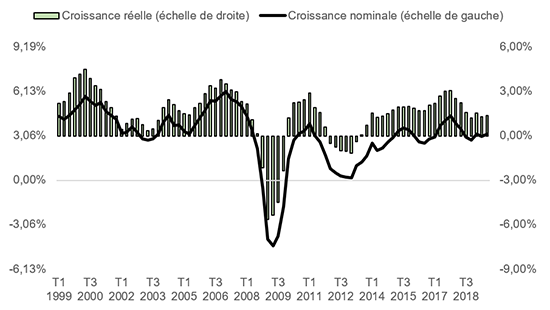

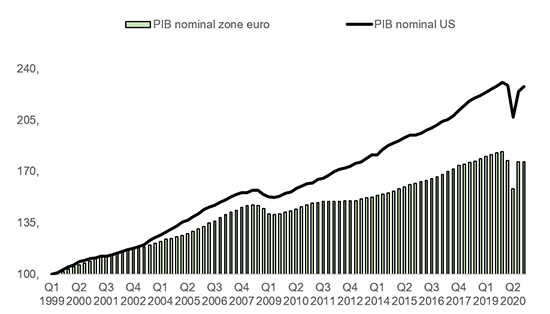

Comparison with the USA

Firstly, while the US faced similar difficulties of sluggish economic recovery in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed's monetary policy - albeit sub-optimal over the last decade - has proven to be more accommodating than that of the ECB. This can be seen in the stronger momentum of US nominal growth, compared to the euro area, after 2008.

While the euro area managed to achieve 82% of the US nominal growth between 1999 and 2007, it achieved only 51.6% between 2008 and 2019. Here again, despite the US economy's decline from its pre-crisis growth trajectory, the euro area has lagged behind even more significantly. This relative decline in European nominal growth compared to that of the United States allows us to compare the relative actions of the two central banks, the Fed and the ECB. This dichotomy has also been reflected in terms of real growth.

The euro area's stagnation

Initially, while the ECB had offered a framework of monetary stability during its first years of existence, the euro area managed to achieve more than 80% of US real growth in the 9 years between 1999 and 2007. In fact, the euro area demonstrated a significant growth potential that allowed the continent to compete with the US over this period on a sustainable basis.

In a second period, this situation was turned upside down by the financial crisis of 2008 and by the failure of the European macroeconomic authorities to stabilise the level of activity. Between 2008 and 2019, the euro area only managed to achieve 38% of the US growth, less than half of what it had achieved in the previous decade. Factoring in the year 2020 adds considerably to this finding. While total real growth between 2008 and 2020 stands at 19.9% in the US, it was only 3.5% for the euro area, or 17.6% of the US figure.

Employment and investment in the wake of the financial crisis

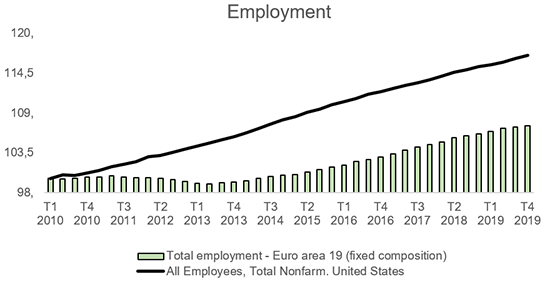

The lower growth in the euro area compared to the US has led to a significant difference in job creation between the two continents. While employment in the US grew by 17% between 2010 and 2019, it grew by only 7.2% in the euro area, or 42.7% of the US total.

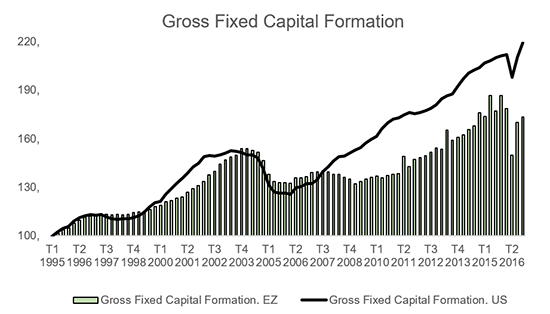

This difference can be seen in the level of investment. In the first period, the euro area saw the level of its investment grow, in nominal terms, by 51.6% between 1999 and 2007, compared with 54% for the United States (or 95.6% of the US total). Then, between 2008 and 2019, investment grew by 21.5% in the euro area compared to 39.7% in the US (or 54.1% of the US total).

A comparison of economic trajectories between the euro area and the United States over the last two decades shows a fracture between two distinct periods. While the euro area managed to follow the US trajectory in the years 1999-2008, the following decade witnessed a massive downturn in the euro area compared to the US. Whether by its sudden nature in the aftermath of the financial crisis, or by comparing it to the US dynamic, the European economic slowdown also affected the euro area's debt levels.

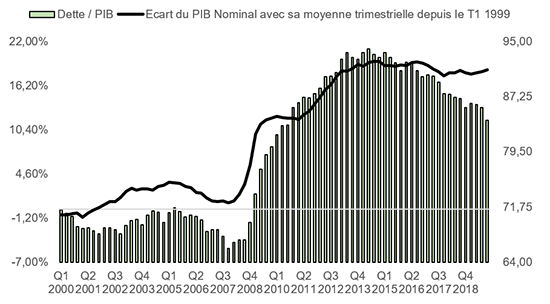

Nominal instability and debt

While the macroeconomic framework of the euro area is based on the concept of stability, the European budgetary rules - between a 3% deficit and 60% debt - are inextricably linked to the nominal growth of the European Union as a whole, and therefore to the monetary policy implemented by the ECB. Indeed, according to the "Maastricht hypothesis", nominal growth of 5%, coupled with a budget deficit of 3% (3% representing 60% of 5%) allows the level of indebtedness to stabilise at 60% of GDP.

However, while the analysis of the euro area's debt trajectory has regularly been limited to the dynamics of public spending within Member States, it appears that the role of nominal instability has been significant in the progression of the euro area's debt in recent years. The observation of the nominal GDP trajectory shows a mismatch between the euro area's nominal GDP and its average growth trajectory, revealing macroeconomic instability within the ECB's control.

However, it appears that the difference between the trajectory of nominal GDP and its previous average growth rate is perfectly correlated with the increase in the euro area's debt in relation to its GDP.

According to this rationale, the decrease in euro area nominal GDP compared to its previous average can be seen as the main cause of the increase in euro area debt. The inability of the ECB to ensure a stable nominal framework through its current strategy is then seen as the monetary cause of the difficulties encountered regarding the euro area's fiscal trajectory.

The ECB's inflation target: an inadequate strategy?

A restrictive interpretation of the concept of "price stability"

According to article 127-1 of the Treaty[4] : "The primary objective of the European System of Central Banks (hereinafter referred to as "the ESCB") shall be to maintain price stability. Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ESCB shall support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union. The ESCB shall act in accordance with the principle of an open market economy with free competition, favouring an efficient allocation of resources, and in compliance with the principles set out in Article 119".

Initially on 13 October 1998[5], the ECB developed a so-called quantitative definition of "price stability: "Price stability shall be defined as a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%". Then, on 8 May 2003, following a "strategic review" procedure, the ECB stated: "Today, the Governing Council confirmed this definition (which it announced in 1998). At the same time, the Governing Council agreed that in the pursuit of price stability it will aim to maintain inflation rates close to 2% over the medium term. This clarification underlines the ECB's commitment to provide a sufficient safety margin to guard against the risks of deflation".

Following this clarification, the ECB's objective since then has been to keep inflation "below but close to 2% over the medium term". By defining the concept of price stability in this way, the ECB sets the rules for European monetary policy.

Firstly, the inflation measurement tool was to be the HICP, a global measure of inflation incorporating energy prices and certain food categories, and not the HICP "Core", a more restrictive measure of inflation that does not take into account certain of its components, which are sometimes considered too volatile. By making this choice, allowing the ECB to gauge itself against an index that is more faithful to the feelings of the citizens of the euro area, the ECB nevertheless stopped monitoring the HICP Core, which would reflect the consequences of the ECB's action more faithfully. Indeed, by acting directly on the level of domestic demand in the euro area, the ECB cannot impact prices that depend on other factors, such as oil prices, which are nevertheless included in the HICP measure.

Secondly, by setting a target "below but close to 2%", the ECB has made the explicit choice of an asymmetric (lower) target, the result of which has been to establish the 2% threshold as a ceiling.

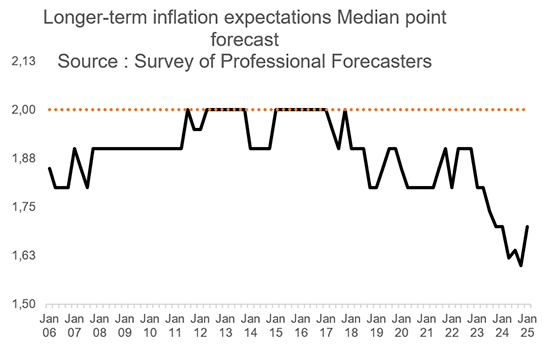

Finally, by choosing a "medium-term" horizon, the ECB has indicated that its action will be guided, not in response to actual inflation, but according to inflation expectations, notably as measured by the "Survey of Professional Forecasters[6]" published quarterly by the ECB.

The un-anchoring of inflation in the euro area

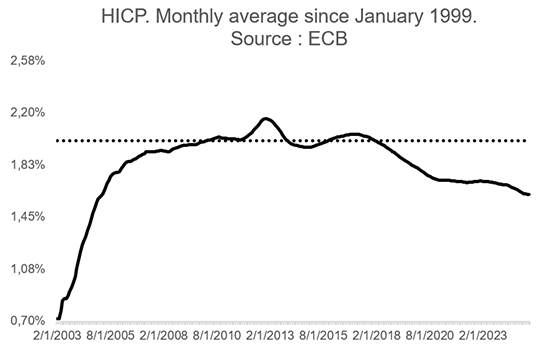

As Christine Lagarde pointed out in her speech on 30 September 2020, the rate of inflation in the euro area has experienced two distinct periods. Monthly average HICP inflation was 2.14% between January 1999 and August 2008, then 1.21% between September 2008 and March 2021, i.e. a fall of 43.5% between the two periods.

The average measure of HICP inflation, since January 1999, totalled 1.61% in March 2021.

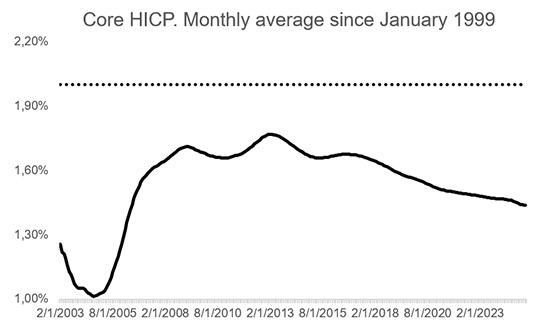

If HICP inflation shows an average rate of below 2%, the HICP Core index shows an even lower rate: 1.44% on average in the euro area between January 1999 and March 2021.

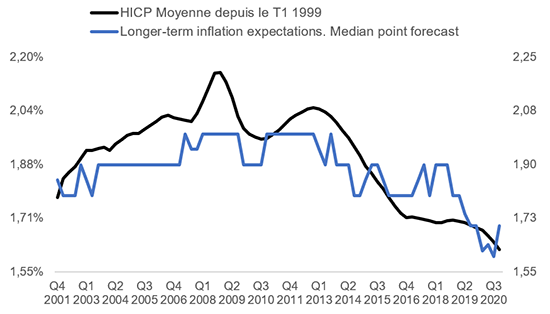

However, as Christine Lagarde points out, "underlying inflation measures are more responsive to economic slack and tend to better predict inflation over the medium term." In other words, HICP Core Inflation better reflects the ECB's action on the level of activity in the euro area, making it a more accurate indicator. Finally, the weakness of the HICP Core over the whole period reflects a clearly sub-optimal situation for European monetary policy. While these measures, HICP and HICP Core, relate to "realised" inflation, the ECB needs to keep a close eye on expected inflation levels. According to the Survey of Professional Forecasters, long-term inflation expectations have never moved above 2%. It appears that the mandate of "below but close to 2%" inflation has been internalised by market participants who consider the 2% threshold as an effective ceiling.

In this respect, it is remarkable to note that expectations from the Survey of Professional Forecasters have correlated strongly with the monthly average of the HICP since the beginning of 1999, suggesting that long-term forecasts of European inflation are in line with the average results obtained in recent years.

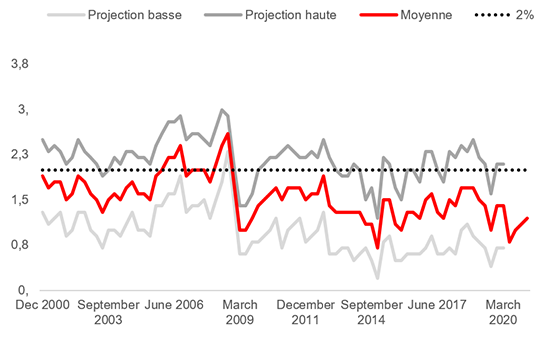

As with other measures, ECB economists' inflation expectations - within a 2-year timeframe - have been persistently below 2% since the 2008 financial crisis.

So, whether for actual or expected inflation, the ECB has found itself in a position of marked weakness in terms of inflation, particularly since the financial crisis of 2008. This situation poses a threat to the anchoring of expected inflation at a level of 2%. Indeed, the ECB's inability to ensure a return of inflation to a level "close" to 2% has resulted in operators being convinced of the lasting weakness of inflation in the euro area, a sign of the ECB's loss of credibility in its action.

The monetary policy review is an essential step in giving new meaning to the objective of price stability

In the context of a clearly sub-optimal monetary policy - as can be seen from the nominal indicators - the ECB Governing Council has chosen to organise a procedure for evaluating its actions, as well as a reflection on the very definition of its "price stability" mandate. On this occasion, and in a timeframe scheduled for the second half of 2021, the ECB is preparing to announce a new quantitative definition to replace that of "inflation below but close to 2%".

On 27 August 2020, completing a similar assessment process, the Fed chose to abandon its Flexible Inflation Targeting strategy - close to that of the ECB - in favour of a Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) strategy. In practice, this new target can be divided into two parts. During an economic slowdown that leads to a drop in inflation below the 2% threshold, the Fed will allow itself to support the level of activity until the level of inflation exceeds the 2% threshold and returns to an average of 2% over a predefined period. This first stage corresponds to a "Price Level Targeting" strategy, the objective of which is to achieve a stable average inflation rate of 2% over time. Then, once this "catch-up" period is over, the Fed will return to a more traditional "Flexible Inflation Targeting" strategy. The new FAIT strategy is therefore the result of an observation: the "Inflation Targeting" strategy was deemed unsuitable in the context of a crisis, proving to be sub-optimal in its ability to support an economic recovery in a satisfactory manner.

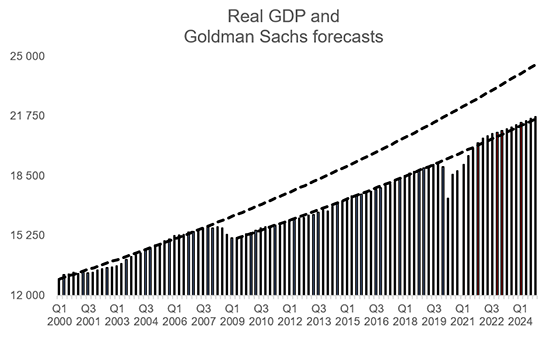

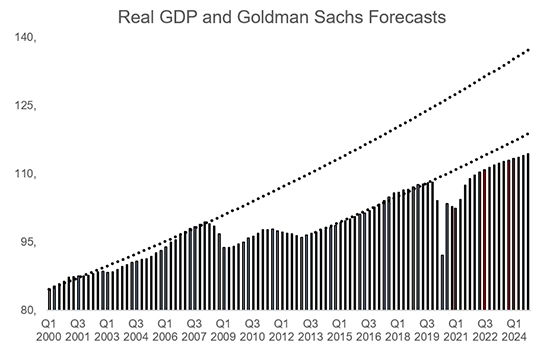

The consideration of this new monetary policy strategy, supported by a massive fiscal stimulus, will allow the US to anticipate a robust economic recovery. Thus, according to current expectations, US real GDP is expected - by 2024 - to be above its pre-crisis trajectory.

Conversely, according to the latest projections, real GDP in the euro area is expected to be 4% below its pre-crisis trajectory, which would correspond to 3 years of "lost" growth.

Faced with a sub-optimal anticipated economic recovery, following a lost decade, the ECB must abandon its strategy of targeting "inflation below but close to 2%". Indeed, it seems ready for such a change, the outline of which are gradually emerging from the speeches made by the members of its Executive Board.

***

During the course of 2021, the ECB has been given the opportunity to change its definition of its "price stability" mandate. Although the transformation hypotheses discussed so far by some members of the Executive Board could lead to a structural improvement in the European macroeconomy, they do not yet seem to be up to the challenge. Indeed, while the euro area is still licking its wounds 10 years after the financial crisis, the severity of the recession linked to the Covid-19 epidemic could prolong the relative decline of the European economy, whether vis-à-vis the United States or China, whose GDP will overtake that of the euro area in 2021. Faced with this situation, and in view of the fact that the "Inflation Targeting" strategy is clearly ineffective in correcting the effects of a major crisis, the ECB must significantly modify its strategy.

Thus, following in the footsteps of the Fed, the ECB could implement the same "Flexible Average Inflation Targeting" strategy, allowing it to correct the effects of the current crisis as quickly as possible, while at the same time accepting a commitment to reflation in the euro area economy after a decade of stagnation.

Paradoxically, a redefinition of the ECB's objective could potentially be more innovative and ambitious than the reform undertaken by the Fed on 27 August. Indeed, by positioning itself in favour of a partial or total Price Level Targeting mandate, the ECB would give itself the capacity to pursue a growth trajectory in line with its full potential in a sustainable manner, without calling into question its price stability mandate.

Finally, and considering the current direction taken by the Fed, which is moving ever closer to a nominal GDP target per level, it is up to European governments to tackle the essential question of the ECB's mandate.

Because, whilst the Fed has to follow a dual objective of inflation control and maximum employment, the ECB has only a single priority objective of price stability. By including the quest for maximum employment in the ECB's mandate, through a revision of the Treaties, the European governments would open the door to the application of a nominal GDP level targeting per level for the euro area economy, allowing it to follow a growth trajectory in line with its capacities, without the risk of accelerating inflation. Through its clarity, such an objective would give economic actors a long-term vision of the level of European activity, thus favouring investment and hiring decisions.

Although European monetary conservatism is considered to be the result of the doctrine originating from the Bundesbank, it appears that the position of the Banque de France has not been any more "flexible" over the last decades. Moreover, in a geopolitical context marked by the emergence of China, in which Beijing wants to support its autonomy - a position revealed by the China 2025 plan - the European growth strategy based on exports is under threat. In a context like this, Germany would have an alternative to such a strategy by supporting European domestic demand more massively to offset a relative weakening of export markets. Such an alternative would imply an overhaul of the ECB's mandate, allowing the euro area to benefit from a strong domestic market and which would consequently offer Europe a favourable negotiating position vis-à-vis its international competitors.

[1] The monetary policy strategy review: some preliminary considerations

[2] New Economic Challenges and the Fed's Monetary Policy Review

[3] Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke At the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Conference on the Legacy of Milton and Rose Friedman's Free to Choose, Dallas, Texas October 24, 2003

[4] Official Journal of the European Union

[5] A stability-oriented monetary policy strategy for the ESCB

[6] Survey of Professional Forecasters

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :