Migration

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

-

Available versions :

EN

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

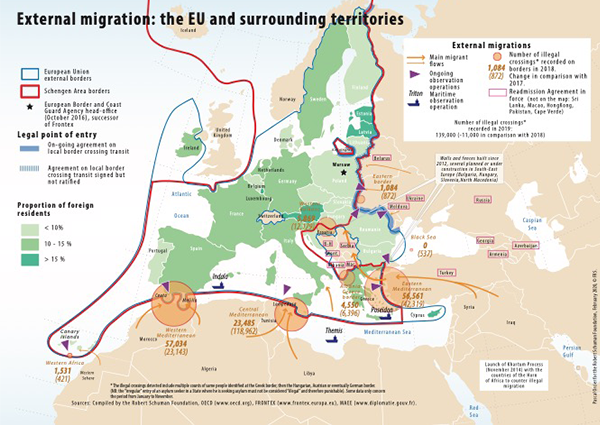

The management of the European Union's external borders is the subject of passionate debate in the European Parliament hemicycle and in many different media in Europe. It also features in a decision made by the European Court of Justice (CJEU) on December 17th 2020 stating that Hungary had been violating European law by turning back migrants as of 2015. Following the latest terrorist attacks on European soil, particularly in France and Austria in the autumn of 2020, the question of European cooperation in the protection of external borders has once again came to the fore. The work of Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, has moreover been the focus of a debate regarding its practices and also its role in "pushbacks", the illegal refoulement of migrants. These debates are taking place just as Frontex is in full "metamorphosis", as suggested by its Executive Director Fabrice Leggeri, since the Agency's budget has increased significantly and its remit progressively strengthened. In a profoundly symbolic gesture, on 11th January 2021, Frontex unveiled its first official uniform: The Agency's personnel will now be armed, a first in the Union's history.

It therefore seems appropriate to analyse in depth the complexities involved in managing the Union's external borders and to take a detailed look at Frontex's work. What meaning do these borders, which are primarily national in nature, have for the Union as a whole? What is the importance of an Agency like Frontex? Which challenges does it face in its mission? How can trust be restored between the Agency, the European institutions, the Member States, European citizens and migrants who wish to cross the Union's borders? And, more importantly, how do we reconcile the protection of human rights with the protection of borders?

The Union's external borders, one of its constitutive factors

According to the definition given by Lucius Caflisch, a border is "a line or space separating land territories over which two states exercise the fullness of their power, i.e., territorial sovereignty". They serve as markers of political identity and are thus a dividing line that provides the basis for interaction with an "outside". According to Michel Foucher, "borders are symbolic markers necessary for nations which are in search of an inside to interact with an outside". Moreover, borders and the areas that surround them are highly mediatized and often politically instrumentalized. The external borders of the European Union are no exception to these observations. Historically tumultuous, they have been extended several times, going hand in hand with the Union's enlargement, first to the South and then to the East, and more recently, they narrowed as the Union lost 12,429 km of coastline following Brexit.

Europe's external and internal borders are central to European integration. The unique political nature of the European Union (neither a federation, nor a confederation of States, nor an international organization) means that tensions, rapprochement and estrangement have occurred along its borders throughout its recent history. To date, the European Union has approximately 67,571 km of coastline and 14,647 km of land borders that it shares with twenty-one third countries.

When European integration began, the external borders were not understood as common borders and the internal ones were still heavily controlled and secured. To give European integration a boost in the 1980s, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and French President François Mitterrand wanted to add a political dimension to economic integration, to create a "Europe of citizens". This led to the genesis of the Schengen area, which established free movement for European citizens within the Union. A political idea intended to respond to the fears of Interior Ministers in the face of security threats, it could only be achieved by adding explicit clauses regarding external border controls, which were set out in the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of June 14, 1985. This first expression of the importance of the Union's external borders also represented the beginning of the transfer of responsibility for border management and security concerns to the border states. In this context, it should be noted that the Schengen area originally comprised only five States[1], as opposed to twenty-six today, and that its neighbourhood was therefore much less conflictual.

Although internal borders have lost some of their importance, the external ones have retained the same qualities and now crystallize the same concerns: migration, security, customs and health. The difficulty lies in the fact the European Union does not have the "regalian" powers with which sovereign States manage their borders. The risk is therefore that the management of external borders remains solely a matter for neighbouring and border States, for example Greece, Italy or Spain.

The European Union expresses interests in protecting and securing its borders, as indicated by European treaties, particularly Article 3 §2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU): "The Union shall offer its citizens an area of freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of persons is ensured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime."

This area of freedom, security and justice is one of exception for Europeans. In its form, it is unique in the world. The external borders of the Union are both national and common. This responsibility is often a heavy burden to bear for some Member States, as the example of Greece in 2020 showed when tensions with Turkey escalated to such extremes that open conflict could have ensued. To overcome this, the Union is trying to "communitarize" the control of its external borders and to create de facto solidarity between Member States. Hence article 77 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) stipulates that the Union "shall develop a policy with a view to [...] the gradual introduction of an integrated management system for external borders".

Politically European leaders have expressed their wish to step up control of the external borders, for example during the videoconference of Home Affairs Ministers on 14 December 2020, when the political leaders held a first discussion regarding the Commission's proposal for a New Pact on Migration and Asylum. While it is obvious that the implementation of a common migration policy will still encounter obstacles, the control of the external borders seems to be an a priori for its success. In order to move towards a Europe that can assume its responsibility to receive refugees and meet the European market's labour requirements, the question of external borders is of prime importance.

Frontex, an actor in the name of solidarity between Member States

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex is the expression of a certain sharing of responsibility and solidarity between Member States. Its creation and strengthening can also be interpreted as a political step forward that aims to avoid the nationalization of the migration issue. Within this framework, the Agency is a constituent element of the Union's migration and security policy.

In response to the political crisis of 2015, caused by a significant influx of migrants on European soil, Jean-Claude Juncker, then President of the European Commission, responded by reshaping Frontex. And so, the European Agency for the Management of Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union, created on October 26th 2004 by Regulation (EC) 2007/2004, became the European Border and Coast Guard Agency on October 6th 2016. It was established by Regulation (EU) 2016/1624.

In 2018, despite a decline in the number of asylum applications, political discussions regarding the migration issue persisted. Jean-Claude Juncker then proposed that Frontex be strengthened, that the Agency be provided with 10,000 agents who could be called to action, and that it be equipped with its own ships, planes and vehicles. The deployment of 10,000 border guards was to be extended until 2027. With Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, it was agreed that the corps should comprise border and coast guards employed by the Agency, as well as seconded staff from the Member States. A rapid response reserve was created for urgent border interventions. In addition, the 2018 regulation required Frontex to have 40 active agents committed to the protection of human rights before the end of 2020 - a requirement that has yet to be met. The cost of the consolidation totalled 1.3 billion € over the period 2019-2020 and is estimated at 5.14 billion € over the period 2021-2027. "This Regulation addresses migratory challenges and potential future challenges and threats at the external borders. It ensures a high level of internal security within the Union in full respect of fundamental rights, while safeguarding the free movement of persons within the Union. It contributes to the detection, prevention and combating of cross-border crime at the external borders".

The remit of the permanent staff has also evolved: The Agency is now able to support Member States with return procedures by identifying undocumented third-country nationals and assisting national authorities in obtaining the necessary travel papers. As shown in Figure 1, there is a significant gap between the number of return decisions and the number of actual returns. Giving Frontex part of the responsibility for returns is expected to improve[2] this situation and in particular to reduce the number of situations in which migrants find themselves without documentation for a long period of time. In addition, cooperation with third countries is strengthened, allowing the conclusion of new agreements going beyond the current limitation to countries in the Union's neighbourhood.

Graph 1

Source: Frontex · Risk Analysis for 2020

Frontex's work - between the management of migration and security challenges

According to Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Frontex's remit covers the integrated management of external borders, analyses of border risks and vulnerabilities, technical and operational assistance to Member States (and third countries) in joint operations and rapid interventions, assistance to Member States in search and rescue operations for persons in distress at sea and the organization and coordination of return operations for migrants.

A) Migration control

Migration is the responsibility of the Member States. However, border States are not always able to cope with new arrivals on their own. In these situations, Frontex can work with them and provide assistance. The deployment of agents can be understood as a step towards greater solidarity.

According to data published by the Agency in 2020, Frontex rescued 13,170 people from drowning at sea, arrested 742 migrant smugglers and removed 12,000 people who did not have the right to enter European soil from the external borders.

The vocabulary of migration is very complex. Most often, in the public debate, a distinction is made between asylum seekers (people seeking international protection outside their country's borders) and "economic migrants" (those seeking a better life).

The European Union attracts migrants from a wide variety of personal and geographical origins. While most of them seek to join the Union via legal means, a sizeable proportion attempt to cross borders through irregular channels. Within this category, two different situations can be identified. Firstly, asylum seekers whose political or personal circumstances do not allow them to comply with regular immigration procedures. Indeed, Article 31 §1 of the Geneva Convention of 1951 prohibits the punishment of asylum seekers who have crossed borders illegally, provided that they arrive directly from countries where their lives were in danger and/or have valid reasons for violating the rights of entry. Second, some people try to bypass checkpoints because they do not have a legal right of entry.

In fulfilling its remit, Frontex's function is to monitor the external borders of the Union, identifying and directing people who do not pass through the checkpoints. Frontex and its agents operate in an environment framed by the legal texts of the Union and the international community but which is highly complex given the reality of the facts. On the one hand, European borders in the South are marked by strong tensions: for example, during the crisis between Greece and Turkey in the Mediterranean Sea in 2020, two Frontex agents were injured by gunshot. On the other hand, even in less conflictual situations, the sea is an area where the delimitation and protection of borders is more difficult to establish than on land.

To clarify this complexity, Regulation (EU) 656/2014 defines the rules for border surveillance as follows: "It establishes greater legal certainty in the context of operations on external sea borders, and the provisions and rules concerning interception, rescue at sea and disembarkation. It emphasizes safety at sea, the protection of fundamental rights and the principle of non-refoulement. It distinguishes between the different rules and procedures concerning interception on the high seas, in territorial waters and in contiguous zones".

By recalling the international laws established in existing conventions, a large part of this Regulation is devoted to human rights and fundamental rights. It stipulates that the refoulement of those who wish to apply for asylum is strictly prohibited (principle of non-refoulement). Any person who wishes to do so must have the opportunity to submit his or her asylum application and have it examined. The judgment delivered by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the case Hirsi Jamaa and others vs. Italy dated 2012 was a landmark for similar cases.

However, Frontex has the right to intercept boats (sections 6 and 7 of the 2014 Regulations). If the Coast Guard has reasonable grounds to suspect that those on board are involved in criminal or illegal activities, it can intercept them to obtain more information and then either direct the boat to a checkpoint or ask it to change course to return to its point of departure. When this involves a boat of migrants, the interception technique is often used by national and European agents to identify traffickers and thus move forward in the fight against criminal networks involved in the - often lethal - trafficking of human beings.

Another of Frontex's tasks is to assist in rescue and search operations at sea. Indeed, many migrants place their trust in traffickers who take them on board vessels that are ill-adapted to the conditions on the high seas. A significant number of migrants lose their lives while trying to come to Europe. Between 2014 and 2020, 20,782 people lost their life as they tried to cross the Mediterranean. International conventions of maritime law, such as Article 98 of the UN Convention on the law of the sea, stipulate that any boat that finds another in distress must try to save the people on board. Frontex applies this law and fulfils its mandate by assisting in rescue operations. As soon as Frontex identifies - by means of surveillance - a vessel in distress (often without an engine), all maritime surveillance centres in the region are informed and Frontex assists them by saving the lives in danger.

B) Combating crime

Irregular migration is closely connected to criminal networks. The most profitable form of trafficking is that linked to migrants, more than that linked to drugs. Often people who misuse human beings are also involved in the trafficking of weapons, drugs, organs, etc.

Border control is not only about migration. In 2020, Frontex arrested 453 drug traffickers, seized 147 tons of drugs and 146 weapons. The Agency also confiscated 3,885 false identity documents. In the same year, marked by the health crisis, Frontex has had to face other challenges: trafficking of medicines, sanitary materials and false sanitary authentication documents[3]. Other criminal activities that Frontex seeks to detect include organ and child trafficking.

Regarding the fight against crime in a wide variety of forms, Frontex works in close cooperation with the Member States and other European agencies. As part of the EMPACT (European Multidisciplinary Platform against Criminal Threats) operations coordinated together with Europol, Frontex arrested 75 human traffickers, 1,819 kg of drugs, 419 child traffickers, 423 false documents, 384 stolen cars and identified 249 potential victims of child trafficking[4].

Frontex's security control is carried out through the Schengen Information System (SIS) and the SLTD (Stolen and Lost Travel Documents Database). Frontex is also committed to countering terrorism. Working with Europol, Frontex detects foreign fighters using the Common Risk Indicator manual developed by the two agencies. With Eurosur (European Border Surveillance System), which was launched in 2013, Frontex has a secure information network through which Member States can exchange intelligence quickly and easily.

Cooperation between Eurojust and Frontex is part of the fight against serious cross-border crime, including the fight against smuggling of migrants and human trafficking. The two agencies have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that establishes the different types of cooperation and the means that can be implemented.

For effective border surveillance and precise control, Frontex needs modern equipment that is adapted to the different types of criminality that the agents face. In this sense, the Agency's increasing budget is also being used for the improvement of the agency's equipment, such as the purchase of drones.

A question of confidence

Good management of external borders can only be built in a climate of trust. To achieve a common migration policy, Member States need to trust each other. Member States that are not on the external borders of the Union are, however, concerned by their management and by the arrivals of asylum seekers and migrants. In this respect, Frontex, as a Community and intergovernmental agency, can play an important role. Moreover, it is essential for the Agency to remain intergovernmental in nature so that States continue to be actively involved.

Furthermore, this involves (re-)establishing trust between Frontex and the European institutions, which has been publicly challenged by a press campaign. To return to a constructive climate, it is important to give more supervisory control to the European Parliament - some members of which have strongly criticized Frontex. Moreover, it seems that communication between the Commission and the Agency does not live up to expectations. More transparency and closer cooperation are necessary, especially to avoid bureaucratic delays and mutual finger-pointing.

There is also a need for trust between European citizens and their border and coast guards. Frontex is going through a period of transformation in terms of manpower, budget and equipment. This implies a paradigm shift, which should be explained and be the subject of a clearer and more transparent information campaign. More constructive involvement of the European Parliament would be useful in this respect.

Finally, Europe needs to improve the way it communicates with the outside world and to better define the legal procedures required for entry into Europe. It needs to ensure that asylum applications are processed fairly, quickly and efficiently at border checkpoints and that everyone who has the right to live in Europe will get it. To achieve this, the Union's migration policy must be thought out anew.

In the Commission's proposal for a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, this issue is amply addressed but the problem regarding the legal paths to migrate to Europe is not adequately developed. It should be remembered that while in 2018 EU consulates issued 14.3 million visas, a third of those requested in Africa and Haiti were refused[5]. Arriving in Europe as a migrant in illegal circumstances cannot lead to a better life.

Trust can only be shown in a climate of absolute respect for human rights. For this, the legal bases and mechanisms exist: Frontex is first of all governed by a Code of Conduct and has signed numerous partnerships with international refugee and migrant organizations, as well as with non-governmental associations.

Secondly, the Agency has had a Consultative Forum on Human Rights since 2012. Its members include the International Organization of Migration, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which also has a liaison officer at Frontex, the European Agency for Fundamental Rights, the NGOs Save the Children and the Red Cross, etc.

Moreover, within Frontex, an independent Fundamental Rights Officer, established by Article 104 of Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, reports to the Agency's Management Board (which comprises two representatives of each Member State and two representatives of the Commission). Under the aegis of this officer, forty fundamental rights officers are due to be deployed (with the support of the Fundamental Rights Agency according to Frontex's enhanced remit). This has not yet been carried out and should be done as soon as possible with an additional effort on the part of Frontex and the European Commission to overcome the bureaucratic obstacles that have delayed this implementation.

***

All of these existing measures aim to protect human rights in a highly complex, tense, and sensitive context. They should be used to the maximum. While it is very important to have a debate at European level regarding Frontex's missions and functioning, we should recall the need to work constructively for the establishment of an integrated and solidarity-based protection of the European Union's external borders, as well as a holistic migration policy of the Union. An agency like Frontex is indispensable for these two objectives.

[1] Germany, France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium

[2] The Commission's proposal for a new Pact on Migration and Asylum (presented in September 2020) stipulates that the post of a Return Coordinator will be created under the aegis of Frontex, which will give the agency an even greater importance in the area of returns.

[3] Frontex report Frontex 2020 in brief,

[4] Idem

[5] Michel Foucher, Les frontières,, CNRS editions, Paris, February 2020.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

Ukraine Russia

Alain Fabre

—

11 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :