Freedom, security and justice

Ramona Bloj,

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

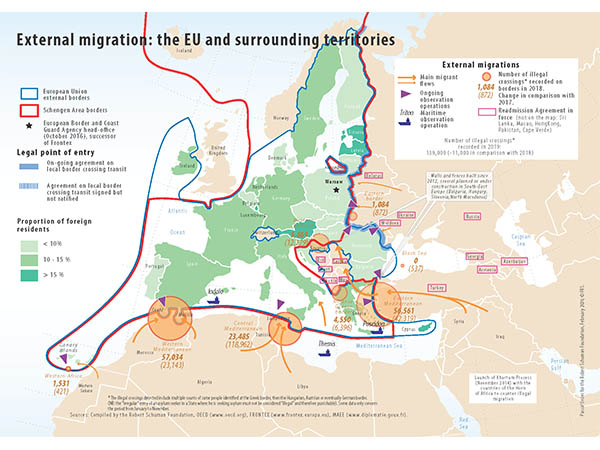

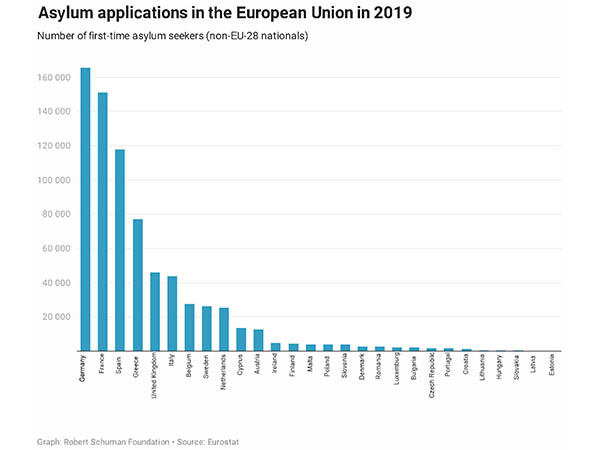

In 2019, 22.9 million people or 4.7% of the total population of the European Union were non-European citizens. According to the European Commission, in the same year, the Member States granted 3 million first time resident permits to third country citizens. Whilst the number of asylum requests totalled 1.28 million in 2015, it decreased to 689,000 in 2019.

Across the Union, figures vary from one country to another: if we look at the number of migrants in 2019, Germany took in the most with 13.4 million, i.e. 15.7% of its population, followed by France (8.3 million), Spain (6.5 million) and Italy (6.2 million). In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland, according to the OECD was the leading destination of temporary working migrants, ahead of the USA; in 2018 Poland delivered more than a million new permits to extra-European workers.

In terms of migration policy, the European Union has a shared competence - its intervention depends on the application of the principle of subsidiarity and is closely linked to the creation of the Schengen area. Article 79(1) TFEU defines the objectives of the Union in this area: "The Union shall develop a common immigration policy aimed at ensuring, at all stages, the efficient management of migration flows, fair treatment of third-country nationals residing legally in Member States, and the prevention of, and enhanced measures to combat, illegal immigration and trafficking in human beings".

At European level, a number of mechanisms, instruments and structures exist to ensure cooperation on migration and asylum policy. However, these have proved to be insufficiently used, coordinated and adapted to political and geographical realities. There is, for example, a European Asylum Support Office (EASO), which has very limited means and competences. Concerted returns are provided for in the current framework but are only applied in 30% of cases. The Frontex agency is regularly reinforced: it now has 1,200 border guards and coastguards, compared to almost 300 in 2015, but it often experiences major insufficiencies, especially in times of high influx.

The failure of the current configuration of the European Union's migration policy is identified with the Dublin III Regulation, which in 2013 replaced the Dublin II Regulation adopted in 2003, both of which have their roots in the 1990 Dublin Convention. Despite these two reforms in 2003 and 2013, the most divisive aspect has not been addressed: the country of entry of an asylum seeker is responsible for examining his or her asylum application. In fact, border Member States, such as Greece, Spain, Italy and Malta, are the most exposed countries and therefore the most overwhelmed by the management of migration flows on their territory. Secondly, there are countries such as Germany which, because of its economic attractiveness and the network of migrants already established on its territory, has become a preferred destination for many migrants. A European Parliament study shows that over the period 2008-2017, 90% of asylum applications were concentrated in 10 EU Member States.

The events and trends observed since 2015 have simply revealed the failure and unsustainability of the European asylum policy: the denial of solidarity between Member States, which resulted in a categorical refusal by some States to accept the distribution system (relocation) put forward by the Commission; the numerous shipwrecks of migrants in the Mediterranean Sea; the existence of camps in Libya and the development of migrant smuggling networks; the agreement reached with Turkey in 2016 which provided for the return to the latter of irregular migrants arriving in Greece; the fire of 9 September 2020, which completely destroyed the Moria camp[1].

It was to address these difficulties and shortcomings that a new Pact on Migration and Asylum was presented on 23 September 2020. Indeed, finding a consensus at European level for a new approach to migration is high on the agenda of the Commission chaired by Ursula von der Leyen as announced in her political guidelines in July 2019.

Obligatory but flexible solidarity

Since 2015, Member States at the forefront have been calling for a more sustainable solidarity mechanism. But this quest for solidarity soon turned into a political crisis, creating deep divisions between Member States. The quota mechanism introduced in the summer of 2015 in the wake of a proposal by the Commission then presided over by Jean-Claude Juncker, did not lead to the desired effect since it was not respected by certain Member States, like Hungary and Poland, or was only slightly respected by others such as Austria and the Czech Republic.

The new Commission has made the issue of migration central to its mandate. In her State of the Union address on 16 September, the President of the Commission stressed that "if we are all prepared to compromise - without however accepting the slightest compromise on our principles - we can find solutions". Solidarity, a principle enshrined in the European Treaties, is at the heart of this new approach. However, it will be less binding and more flexible. Unlike previous attempts, the new asylum and migration pact does not provide for fixed relocation quotas, but integrates several forms of cooperation and responsibility sharing, including a sponsorship system.

According to the proposal put forward by the Commission, a new mechanism would be accessible to all Member States facing strong migratory pressure; either the Commission would trigger the mechanism itself after making an assessment, or the State concerned would make a direct request. After triggering this mechanism, the Commission would estimate the number of migrants as well as the needs of the labour market and would propose a distribution plan between Member States, in proportion to their size and economy: 50% of the calculation based on GDP and 50% on population size.

Relocation would therefore always remain an option, but States refusing to receive migrants on their territory would have other options to show their solidarity: they could choose to "sponsor" the return of migrants to their countries of origin, i.e. a Member State would assume responsibility for the return of a person who does not have the right to stay, on behalf of another Member State[2]. For this, they would have 8 months, at the end of which the asylum seeker, if not sent back to his country of origin, would be relocated to the "sponsor" country. This mechanism could prove to be extremely long and difficult, but also limited by international law. To take one example, at present there is no common European list of "safe countries of origin"[3]. Another option open to Member States that refuse asylum seekers would be to assist countries at the front line with expertise or practical help, such as the management of reception centres. States refusing either option could be sanctioned through a mechanism, yet to be defined.

The Commission therefore hopes to avoid the deadlock between compulsory relocation and no solidarity; it is proposing a flexible approach, so that all States can participate and take on clear responsibility. This mechanism would be adapted to three types of situations: rescue at sea, migratory pressure and migratory crisis. Depending on the nature of the situation, the European response could be calibrated and adapted. This would place the Commission in an important position of assessment and management.

The Commission also wants to set up an informal expert group to advise it on its overall migration and asylum policy, taking into account the point of view of migrants. Its first task would be to contribute to the development of a comprehensive action plan on integration and inclusion for the period 2021-2024.

Dublin "put to bed", but the criteria of first country of entry persists

The Dublin III Regulation is the central, but also the most divisive element of European migration policy. To find a solution that is better adapted to the reality of migration, this regulation would be "put to bed" (shelved) to quote Margaritis Schinas, Vice-President of the Commission in charge of migration and promotion of the European way of life. It will therefore be replaced by a different approach.

However, the central element of this regulation would not be completely removed: the first country of entry would remain one of the criteria for deciding which country is responsible for handling asylum applications. Nevertheless, these criteria would be prioritised differently: the country responsible for the asylum application could be the one in which an asylum seeker has a brother, a sister or his "nuclear family" (contrary to the current situation, where the presence of the nuclear family is the only valid criterion), or in which he has worked or studied. The project maintains the possibility - which has not been used enough so far - of filing an asylum application in a Member State which has already granted him/her a residence permit or visa. This is called the existence of migration networks. Otherwise, first-arrival countries will still be responsible for managing applications, but in the new hierarchy proposed by the Commission, this is now the fifth criterion.

The security dimension: Very strong emphasis on returns

The New Pact on Asylum and Migration places a strong emphasis on better management of external borders and returns, thus further strengthening the security dimension, which has been the main approach to migration management over the years, as shown by the introduction of the Schengen Information System (SIS), Eurodac, the Integrated System of External Vigilance, Frontex and readmission agreements with third countries.

Firstly, "sponsorship" of returns would be possible. This links the question of returns to the issue of solidarity. A bitter marriage for some observers.

Secondly, migrants should know more quickly whether they have the possibility and the right to stay in Europe or whether they should return to their country of origin. This should be achieved through compulsory "screenings" of all asylum seekers arriving at the external borders of the Union. These screenings would consist of identification, health checks and fingerprinting and the recording of these data in the Eurodac database[4]. Thus, the new asylum and migration pact would strengthen the already existing database. It would also provide for the harmonisation of asylum legislation at European level, a priority pursued for many years - the 1990 Dublin I Regulation already tried to tackle this issue. In addition, the Commission's proposal aims to transform the current European Asylum Support Office (EASO) into a fully-fledged EU asylum agency, which would be responsible for ensuring convergence in the examination of applications for international protection and providing operational and technical assistance to Member States.

Thirdly, returns should be executed more quickly. The proposal foresees the establishment of a fast-track process for migrants whose asylum applications are likely to be unsuccessful. These are nationals of countries with a positive response rate to asylum applications of less than 20%, such as Tunisia or Morocco. In these cases, the asylum application would be processed at the border and within 12 weeks. Ylva Johansson, European Commissioner for Home Affairs, stressed in a hearing at the French Senate on 5 November 2020 that an accelerated process would avoid the permanent settlement of migrants, such as professional or social integration, who do not have the right to stay and would thus facilitate the return for the administrations, but also for the migrants themselves.

Fourth, returns should be executed more efficiently. This should be made possible through the conclusion of new agreements, much broader than those currently in place, with third countries. So far, the European Union has concluded 18 readmission agreements (Albania, Moldova, Armenia, Montenegro, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Cape Verde, Serbia, Georgia, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, Turkey, Macao, Ukraine, Macedonia, Kazakhstan). It also has six readmission "schemes" (Afghanistan, Guinea, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Gambia, Côte d'Ivoire). The Cotonou Agreement also contains provisions on the return of irregular migrants.

However, one of the major problems concerning returns is collaboration with these third countries and their political stability. Often, they are neither ready willing nor able to facilitate the return of their nationals. This often makes returns very slow and, in many cases, impossible, with extremely harmful effects not only for the functioning of the European migration system, but also for the personal situation of migrants who often live illegally and without social protection for a long time.

To solve these difficulties, the Commission is proposing to create a new post of European coordinator for returns under the aegis of Frontex, as well as a network of national experts who would ensure that return policy is consistent across the EU. This is one of the elements that would, among other things, guarantee Frontex additional resources.

New Partnerships with third countries

In its proposal, the European Commission underlines the importance of considering migration in a more comprehensive and systematic way. This is most evident in the section concerning cooperation with third and/or partner countries. Partnerships should go further than those concerning returns: migration and asylum should, according to the Commission, be taken into account in all areas of the Union's external policy, such as in development aid and more precisely, in economic cooperation, the areas of science and education, digitisation and energy, etc.

The Commission therefore would like to build better channels of communication with third countries, but also with their populations, regarding legal channels of entry into Europe and visa policy. The notion of "partnerships to attract talent", mentioned in the new pact, seems to go in the direction of a common policy on legal labour immigration, but its main features remain very vague for the time being.

In addition, the Commission wants to cooperate more closely with third countries in the judicial and policing fields, notably with the help of Europol, to combat the trafficking of human beings. The proposed EU asylum agency would also play an important role in establishing such cooperation. Considering the complexity of these partnerships, particularly with countries where governments are not very cooperative, it remains to be seen how this could be effectively implemented.

What improvements for migrants' rights?

Some NGOs working with migrants and refugees regret the focus on returns and not on the human being. With regard to the new sponsorship system Judith Sunderland, Acting Deputy Director of the Europe and Central Asia Division of Human Rights Watch (HRW) declared: "It's like asking the school bully to walk a kid home". Jon Cerezo of Oxfam France would also have liked solidarity to become a reality rather more through the protection of asylum seekers and not in the shape of returns. Caritas Europa regrets the focus on returns, but the NGO recognises several positive developments concerning arrangements to protect the rights of the child and to preserve family unity upon arrival of migrants, as well as the attempt to pay more attention to the protection of fundamental rights at borders and in cooperation with third countries.

Changing the period of time after which refugees are eligible for long-term legal status from 5 to 3 years is also a point that could facilitate integration on European soil.

Response from Member States is generally constructive, but some remain vigilant

Member States welcomed the Commission's new pact and considered it a "good basis" for starting negotiations. The most optimistic responses came from those countries that have been at the forefront of migration pressure in recent years, such as Italy and Cyprus. The President of the Italian Council, Giuseppe Conte, described the new pact as "an important step towards a truly European migration policy", but his Spanish counterpart deplored the lack of a "compulsory solidarity mechanism".

Germany, which currently holds the Presidency of the Council of the Union, is favourably disposed towards this new proposal and wishes to move forward as quickly as possible. Other countries, such as Austria, Estonia, Hungary and the Czech Republic, have a rather constructive approach, but remain vigilant as they do not want to see a compulsory distribution mechanism reintroduced - which is not provided for in the proposal. We note that the majority of countries that remain cautious are those that did not respect the relocation mechanism established in 2015.

Hungary is the country that is most clearly warning against the new proposals, especially the one concerning compulsory solidarity in relation to return sponsorship, which is very difficult to achieve for a "small" country according to the Ambassador of Hungary in Paris Georges Károlyi. The most obvious solution advocated by Hungary remains to "stopping migration". However, the Commission sees the fact that the Commission has not rejected the pact in its entirety as an important step forward.

Countries like Austria, Estonia, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, and Poland - who all see the new pact as a good basis - believe that it contains crucial proposals in the field of returns, partnerships with third countries and border controls. Certain Member States such as Belgium, Spain and Luxembourg have doubts about the implementation of certain proposals in practice - in particular with regard to the functioning of compulsory solidarity and legal migration channels.

Progress in terms of the protection of Human Rights have been stressed by Finland and Ireland, which both demanded efforts to be made in this direction.

***

The Council and the European Parliament will examine the draft pact presented by the Commission. While the German Presidency of the Council has shown a clear willingness to move forward with the negotiations as quickly as possible, the Commission would like to see the proposal adopted before the end of next year. The coronavirus pandemic, but also the extreme polarisation of the public debate on this issue in the Member States, could however make the negotiations more difficult than expected.

The Pact proposed by the Commission will strengthen existing tools and instruments, as well as the security aspect of European migration policy. While it seems more realistic in terms of sharing responsibilities and solidarity, it needs a considerable amount of political will and reaching an agreement between Member States could prove complex, as Ylva Johansson has pointed out.

Migration is a human, structural fact; asylum is a fundamental right for persecuted people and a legal obligation under international law for the States Parties to the Geneva Convention. The area of migration policy will therefore remain crucial for Europe in the future and a new European approach is needed. This pact could then be a "good basis" for moving forward, but it remains to be seen how it can be adapted to different political and migratory realities.

[1] Opened in 2013 on the island of Lesbos in Greece, the camp has been the subject of much criticism, especially regarding living conditions, overcrowding, and its transformation into a detention centre following the agreement between the European Union and Turkey in 2016.

[2] Par-delà la question migratoire : les enjeux du Nouveau Pacte sur la Migration et l'Asile. Entretien avec Jean-Pierre Cassarino, Le Grand Continent, 8 novembre 2020.

[3] Category of country whose citizens cannot benefit from the status of refugee.

[4] The "Eurodac" system allows the comparison of fingerprints for the application of the Dublin Regulation.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :