Economic and Monetary Union

Alan Hervé

-

Available versions :

EN

Alan Hervé

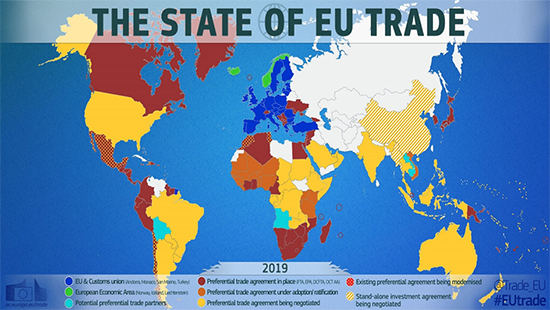

This free-trade bilateralism is not unique to the European Union. The two other giants of international trade, the United States and China, have been negotiating bilateral trade agreements for several years. But they still lag behind the Europeans in this area. The conventional free trade network of the European Union is still more extensive than that of the United States, in particular because of the rejection by the Trump administration of the trans-Pacific partnership project negotiated under the Obama administration, or even China[3], despite the advanced negotiation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership[4]. The hypothesis of a relaunch of trade talks between the European Union and the United States cannot be ruled out, even if the nature of a future transatlantic agreement is still dependent on the personality of the future tenant of the White House. Sino-American tensions could also lead to a rapprochement between Europe and China and allow the completion of a trade and investment agreement between these two trading blocs.

The network of Europe Agreements is also characterised by the diversity of the trading partners involved, both in terms of the level of development as well as from a geographic point of view. With the notable exception of Russia, Central Asia and certain States, excluded for obvious foreign policy reasons (Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, Cuba, Libya), there is hardly a region of the world that has not been affected by the dynamism of European commercial diplomacy.

Although all the current negotiations are still some distance from being finalised, it is nevertheless possible and useful to make an initial critical assessment of this conventional strategy, emphasising its legal and political dimension.

Still uncertain economic results

These free trade agreements have been justified primarily on economic grounds, in line with the Commission's wish to increase access to third country markets and thus boost European competitiveness, growth and employment.[5]. The Commission has also developed the practice of publishing impact studies, which are usually outsourced to external service providers, in an attempt to assess the effects of any future agreements. But ex-post evaluation of the economic impact of free trade agreements has long been wanting. In line with a commitment made in 2015, the Commission now publishes an annual report on the implementation of trade agreements, containing figures on the state of the trade relationship between Europe and its partners[6]. Lessons learned from the economic impact of these agreements, however, remain patchy and difficult to measure. There is some evidence that FTAs generally boost trade flows in the years following their implementation and certainly provide a source of profit and opportunity for export-oriented sectors. However, the real impact of these agreements on employment and economic growth is not clearly demonstrated, especially as it is likely to vary significantly across the sectors and regions concerned. Moreover, the existence of a free trade agreement will not prevent, in the event of an economic, social or health crisis, a downturn or even a reduction in trade.[7]

It also appears that economic operators do not always take full advantage of these agreements, since the take-up rate of the trade preferences they provide for remains limited. [8]. This low take-up of preferences can be explained by a lack of awareness of the potential offered by trade agreements and the difficulty for some firms, particularly SMEs, to adapt to compliance with the rules of origin and customs and regulatory formalities which still condition access to preferences.

Lastly, it emerges that the trade balance between the Union and its partners which have concluded a free trade agreement with it is generally in surplus for the Union, particularly with countries such as Korea, despite the initial fears expressed in Europe at the time of the negotiations. Canada even suffers from competition from European products, particularly in agriculture, and its exporters struggle to adapt to European regulatory requirements.[9]

The Commission's regular review of the implementation of FTAs is welcome, but it is regrettable that the assessments made are based on a rather mercantilist reading of international trade and are essentially limited to listing those sectors of goods and services which have seen their trade increase. The data published do not really allow an assessment of the extent to which the agreements lead to a real diversification in the structure of trade with the countries concerned, particularly in the case of developing countries. There is limited interest in highlighting particular entrepreneurial successes linked to the development of bilateral trade, and a more ambitious study of the macroeconomic impact of EU-negotiated FTAs is still lacking. In order to assess the effects of the Union's conventional strategy, it is necessary to go beyond the mere logic of increasing market access for European companies.

A European response to the crisis of multilateralism

The Union's trade agreements must be seen as a European response to the deep crisis of multilateralism and the continuing weakening of the WTO. The failure of the Doha Round launched in 2001 and, more broadly, the inability of States to agree on new international trade rules have marked the failure of one of the WTO's essential functions, namely to be the preferred forum for the progressive and appropriate regulation of international trade. Even more seriously, it is the WTO's other existential function, namely the capacity of its dispute settlement mechanism to ensure overall compliance with multilateral rules, that is being disrupted. Since December 2019, the WTO Appellate Body, without which its trade dispute settlement procedures cannot function on a sustainable basis, has been paralysed because it does not have a sufficient number of judges. This blockage is due to the veto that the US administration has been exercising for several years against any new appointments.[10].

This episode is part of a deliberate strategy by the United States to challenge the fundamentals of the multilateral trade system built at the end of the Cold War and now deemed contrary to American interests. The same administration has also been behind a series of unilateral trade sanctions justified by the defence of US national security and the fight against unfair trade, aimed particularly, but not exclusively, at the Chinese rival, accused of abusing the benefits of the multilateral system. This climate of trade warfare sometimes results in armistice. But these lulls remain temporary and based on precarious trade arrangements whose content is in open violation of the WTO's basic principles[11]. China is not to be outdone and is also trying to shape a new international legal order more in line with its own interests[12]. Moreover, it would be perilous to believe that a return to normality will be possible after the American elections, since protectionism and the propensity to unilateralism are, in our view, fundamental trends that will continue regardless of who will lead American or even Chinese commercial diplomacy.[13].

The European Union must now face reality. The rules-based multilateral trading system it has enjoyed in recent decades is being weakened, giving way to an unpredictable regime dominated by power politics and a sustained resurgence of international economic tensions. At the end of 2018, the European Union published a series of proposals to reform the WTO, but these have so far failed to produce any real results.[14]. A bilateral solution would therefore appear to be the only realistic way forward and the only way to preserve European interests on the international stage in the long term. The Union's agreements can thus form the basis of a "flexible and differentiated multilateralism"[15] thus preserving the legal certainty and predictability essential for the deployment of international trade and investment.

In substance, the combined analysis of these different texts also reflects a conventional model specific to the European Union, i.e. a strategy of reproducing the negotiated instrumental framework from one agreement to another so as to develop a relatively uniform regime, at least within each major generation of agreements, rights and obligations governing international trade between Europe and its economic partners. This explains why trade agreements are in reality more than mere market-opening agreements, and why they are gradually emerging as mechanisms for regulating international trade.

Moving beyond free trade in favour of bilateral trade regulation

One of the major misunderstandings of the Union's conventional policy is the qualification and perception of the trade agreements it has been negotiating for almost two decades now. Despite media practices and rhetoric that continues to be in vogue within the European institutions themselves, these agreements have in fact become more than just free trade agreements.

It is true that EU agreements still provide for the almost complete elimination of customs duties between the two partners and the opening up of a substantial number of sectors of trade in services.[16]. The elimination of tariffs is without consequence, not least because tariffs in some developing countries are still often high, and also because it has been shown that European tariffs continue to have a significant impact on certain trade sectors, for example in agriculture.[17]. But the scope of the subjects covered by the Union's trade treaties is in fact much broader than trade in goods. [18], and the European negotiator has, over the years, constantly introduced new subjects into the negotiations related to the Union's commercial interests. This is the case for trade in services, the liberalisation of which now constitutes the principle[19] of public procurement, intellectual property and regulatory cooperation.

These agreements also include an internal dispute settlement mechanism, partly inspired by the WTO system, which allows each party to the agreement (the European Union or its trading partner) to initiate bilateral arbitration proceedings. This is a significant development because, until recently, these mechanisms had never been used, with the EU preferring to stick to the multilateral and quasi-judicial mechanism of the WTO. However, with the WTO under threat, the EU may be increasingly tempted to rely on these bilateral arrangements. Two cases initiated under these bilateral procedures in 2019 against the Southern African Development Community (SADC) [20] and by Ukraine[21] are evidence of this which would otherwise have been the subject of a complaint to the WTO.

Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty and the European Union's acquisition of a new competence in the field of foreign investments[22], the Commission has also included the question of the protection of foreign investment in trade negotiations agenda along with mechanisms enabling investors' access to specific tribunals, provided for under these agreements, which can impose penalties on States or the European Union in the event of violation of the rights granted to them[23]. However, following an opinion delivered by the Court of Justice at the end of 2017 on the Union's competence to negotiate and conclude the new generation of trade agreements (Opinion 2/15), the question of investment has been the subject of a specific agreement negotiation which are formally separate from the trade agreements negotiated by the Union and which are then intended to be jointly ratified by the Union and its Member States.[24]. Moreover, the Court has recently accepted that the European approach to the protection of foreign investment, which provides for the establishment of investment tribunals whose awards may be appealed to a court of appeal, is compatible with European law, thus removing a major obstacle to the future of these mechanisms.[25].

Better regulation of international trade relations

The purpose of the Union's trade agreements is to accompany, or even frame, the logic of free trade with a set of rules designed to facilitate trade but also, in some cases, to ensure economically and socially acceptable conditions of competition. This conventional regulation can still be used to address new subjects not covered by WTO rules.

Firstly, the agreement between the European Union and Canada and those negotiated with Japan, Singapore and Vietnam provide for the "establishment of regulatory cooperation" with the aim of approximating regulations likely to affect trade between the parties.[26]. The subject is a sensitive one because "although customs duties on shirts or vehicles are ideologically flat, this is not the case for the use of GMOs, or the traceability of chemical components, or the use of shale gas, or even for animal welfare standards."[27]. However, the objective of these chapters on regulatory cooperation is not, strictly speaking, regulatory disarmament or the imposition of normative harmonization of regulations that may affect trade.[28]. More modestly, the aim is to establish a channel for information, consultation and dialogue between the regulatory authorities of each of the parties. This cooperation is based on a voluntary basis with a view to approximating regulations where possible. In the framework of the Agreement with Canada, the Canadian federal authorities and the Commission services have thus met on several occasions in bilateral meetings. The list of topics discussed - cyber security, animal welfare, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals or consumer safety - is set out below.[29] - demonstrates the extent to which business and societal issues are now intertwined [30].

Trade agreements are also intended to establish equal conditions of competition between the European Union and its partners in line with the rhetoric of the level playing field that pervades economic diplomacy. However, this objective is only marginally achieved in the area of competition law, and even less so in the area of State aid, where trade agreements provide for simple mechanisms of dialogue and cooperation.[31]. The need to achieve a "fair exchange" between partners is most evident in the provisions on strengthening intellectual property rights, which deepen and extend the disciplines already provided for in the WTO framework. Thus, from 2010 onwards, and in particular in the framework of the agreement negotiated with South Korea, the Union obtained from its partners the insertion of provisions ensuring the protection of geographical indications (GIs). However, the aim is not to protect all of the 3,000 protected geographical indications (PGIs) in the European Union but, more modestly, to obtain from the partner the protection of some important ones - for example Champagne or Cognac - and their possible coexistence with already registered trademarks. In practice, the conventional protection of geographical indications differs according to the trading partner. The protected lists can be supplemented, if necessary, in the framework of specialized committees.

Number of GIs protected in trade agreements negotiated by the European Union [32]

Finally, the Union's trade agreements provide an opportunity to include subjects that are only very imperfectly dealt with at multilateral level in the rules of international trade. Pending a hypothetical international agreement on e-commerce[33], the European Union has, for example, managed to negotiate certain provisions that reveal its strategic and economic interests but also its political vision. In particular, it is willing to facilitate e-commerce while allowing the public authorities to impose certain limits on it, notably for reasons of public order or consumer protection.[34]. This applies to the recent proposals for negotiations on digital trade that Europe has submitted to Australia and New Zealand [35]. These texts enshrine the principle of free data flow between the parties to the agreement. Undertakings established in the Union have a direct interest in this free data flow. The European Union thus shares a concern to defend free data flow with the United States, unlike States such as China and Russia which, in the name of digital sovereignty, restrict or even prohibit, in certain cases, the circulation of data outside their territory. On the other hand, the European Union differs from the United States in that it would like trade agreements to recognise the possibility of limiting the transfer of so-called personal data, thus ensuring compliance between trade rules and the European regulation on the protection of personal data (GDPR)[36]. The defence of economic interests combined with that of extra-commercial considerations is found in the chapters devoted to the issue of sustainable development.

Trade agreements as a means of promoting the Union's values on the international stage

Since the Treaty of Lisbon, the agreements negotiated by Europeans have systematically included chapters on sustainable development. In doing so, the European Union is demonstrating its resolve to include trade policy in the pursuit of the objectives and principles of its external action, in particular the defence of human rights, support for "the economically, socially and environmentally sustainable development of developing countries" and the preservation of the environment and the sustainable management of resources.[37].

For example, the EU-Vietnam agreement, which the EU has just approved, includes a specific chapter whose objective is "to promote sustainable development, including through the promotion of trade and investment related aspects in the areas of labour and the environment"[38]. A flourishing market of nearly 100 million consumers, Vietnam is nevertheless the subject of much criticism regarding the way it uses its natural resources (sand, fishing and wood), as well as its respect for social and human rights. According to the European Parliament, child labour and forced labour of political prisoners remain a reality in Vietnam.[39]. Does this mean that the agreement negotiated by the Union could change the situation by offering a virtuous glimmer of market access in exchange for progress on sustainable development? This is doubtful, as the text combines deference to the sovereignty of the parties with the timidity of the commitments made.

This agreement in fact insists on the right of the parties to establish their own internal level of environmental and social protection and to act in these areas as they deem appropriate. Europe and Vietnam certainly undertake not to practise social or environmental dumping.[40]. On the other hand, however, social or environmental protectionism is also condemned.[41]. Similarly, while each party promises to make "continuous and sustained efforts to ratify the fundamental conventions of the ILO", the agreement does not directly oblige them to approve these instruments. To date, Vietnam has concluded 6 of the 8 ILO core conventions, the latest ratification being concurrent with the signing of the agreement with the European Union.[42].

The conventional referral technique is also used in environmental matters. One provision deals specifically with the issue of climate change and refers to the implementation by the parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.[43]. Cooperation and exchange of experience are thus encouraged, particularly in the creation of internal carbon pricing mechanisms or the promotion of domestic and international carbon markets. A comparable mechanism is planned for the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). However, it is itself counterbalanced by the reminder of the "right of sovereignty of States over their natural resources" and their "power to determine access to genetic resources" within the framework of their national legislation.[44]. The agreement still insists on the sustainable management of living marine resources and aquaculture products, at a time when the EU has accused its Vietnamese partner of overexploiting marine resources and turning a blind eye to large-scale illegal fishing practices for several years now.[45]. But once again, while cooperation is encouraged in the implementation of internal policies aimed at conserving biodiversity, the text of the agreement ultimately leaves it to the goodwill of the parties. No monitoring mechanism is organised.

In the event of disagreement over compliance by one of the partners with the provisions on sustainable development, the agreement provides for a specific procedure involving an independent "group of experts" which will submit a report to the parties, possibly accompanied by "recommendations". However, this mechanism as it stands is significantly limited. First of all, it can only be triggered by the parties to the agreement, and not by NGOs or trade unions that may be aware of practices that contradict the conventional commitments. Furthermore, while the party concerned must follow up on this report by providing information on the measures taken to comply with it, there is no question here of "condemnation", and even less of any kind of sanction mechanism. In other words, the protection of sustainable development rules remains political and incentive based. However, this does not prevent the European Union from making use of this mechanism, as shown by the complaint against South Korea for failure to respect freedom of association.[46]. It remains to be seen what the real effects of such an approach will be.

On the issue of human rights, the EU-Vietnam agreement is virtually silent even though Vietnam remains a one-party State which does not recognise freedom of association, freedom of expression, freedom of religion and freedom of the press[47]. This is a clear step backwards for Europeans on the issue, if we compare this agreement with other texts previously concluded between the European Union and its partners, for example the agreement with Colombia and Peru, which qualifies respect for human rights as an essential element, allowing one of the parties to suspend the application of all or part of the agreement in the event of a violation[48].

***

The European Union's ability to negotiate and conclude free trade agreements has been described as a test of its international credibility and a demonstration of its normative power.[49]. A quick assessment of the content of these agreements shows that the Union has indeed managed to go beyond the simple logic of free trade and that the Union already has a large network of agreements that testify to a certain vision of the regulation of international trade, capable of continuing in the event of the collapse of the multilateral system. The fact remains that the Union's conventional model can still be improved and should incorporate more ambitious content - social, environmental and development issues come to mind here, but also subjects that are still insufficiently dealt with, such as security of supply, competition and taxation - if the Union wishes to defend a more balanced and more regulated vision of globalisation.

In the immediate future, the issue of monitoring the implementation of trade agreements is likely to become increasingly important, as evidenced by the Commission's announcement of the forthcoming appointment of a Trade Implementation Officer. The assessment of the economic significance of trade agreements needs to be improved. Similarly, the review of implementation could also include an increased assessment of environmental practices and social and human rights legislation in the partner country.

Annex: Overview of the European Union's bilateral trade agreements [50]

(negotiation, conclusion, provisional or definitive entry into force)

[1] See notably, "A competitive Europe in a globalised economy", COM(2006) 567, 4 October 2006 ; Trade for All, COM(2015)497 final, 14 Oct. 2015.

[2]European Commission Commission Annual Report on the implementation fo trade agreements (1st Jan-31st Dec. 2018), 14 Oct. 2019, p.7.

[3]China's network of trade agreements along with those of other members of the WTO can be consulted on(https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/rta_participation_map_e.htm).

[4]RCEP. Begun in 2012 and actively supported by China as a counterbalance to the draft trans-Pacific treaty initiated by the United States, these negotiations aim to create a vast Asia-Pacific free trade zone bringing together the 10 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea and New Zealand.

[5]COM(2006) 567, op. cit.

[6] See notably the European Commission, Annual Report, op. cit.

[7] According to figures given by the Commission, for example, trade in goods decreased between the EU and South Korea in 2018 by 1.5%, similarly, there was a decrease in the trade in goods between 2017 and 2018 of 2.4% between the European Union and Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

[8] In 2018, the rate of preference uptake by European exporters was 90% for a country like Turkey (with which there has been a customs union for more than two decades). It was 81% for exports to South Korea, 77% for Switzerland and around 70% for Colombia and Ecuador. It fell to 37% for Canada (source: European Commission).

[9]The same applies to French exports which, two years after the implementation of the CETA, had increased by 16%.

[10]However, the EU recently proposed, with the support of 16 other members, to maintain an appeal mechanism in the form of arbitration (see the declaration of trade ministers meeting in Davos on 16 January 2020).

[11]As an example see the so-called Phase 1 agreement concluded between the American administration and the Chinese government in January 2020: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/phase%20one%20agreement/Economic_And_Trade_Agreement_Between_The_United_States_And_China_Text.pdf

[12]G. Shaffer & H. Gao, 'A New Chinese Economic Law Order?', 21 University of California, Irvine Legal Studies Research Paper Series (2019).

[13]H. Bourguniat, Le Protectionnisme avant et après Trump, Dalloz, 2019.

[14]See European Union Concept Paper on WTO reform, 18 Sept. 2018.

[15]Regarding this idea see Ph. Moreau Defarges, " Le droit dans les relations internationales: plus qu'un instrument? ", Politique étrangère, 2019/4, pp. 9-22.

[16]In line with provisions in articles XXIV of the GATT and V of the AGCS.

[17]M. Cipollina et L. Salvatici, "On the effects of EU trade policy: agricultural tariffs still matter", European Review of Agricultural Economics, 2020, n 1, p. 1-35.

[18] If we exclude the Economic Partnership Agreements which for the time being focus especially on the trade of goods.

[19] In particular since the negotiation of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the European Union and Canada. Prior to the CETA, the European Union's trade agreements were based on the principle of so-called positive lists of liberalization commitments, which meant in practice that, in the absence of a specific liberalization commitment, a sector of trade in services was not open to liberalization. The most recent agreements are based on the principle of negative lists. Thus, all services covered by the agreement are now liberalised, unless the parties have specifically provided otherwise.

[20]This complaint, lodged in June 2019, concerns the import regime for poultry set up within this regional integration. The dispute is currently the subject of bilateral consultations.

[21]This is a restriction on the export of untreated softwood lumber. After a phase of consultations that did not resolve the dispute, the European Union formally requested arbitration in February 2020.

[22]See in this sense the wording of Article 207 TFEU.

[23]These include national treatment, fair and equitable treatment and protection against expropriation, whether direct or indirect.

[24]ECJ, Opinion 2/15 delivered 16 May 2017. The Court thus considered that investments other than direct investments and the settlement of investor-State disputes were a competence shared between the Union and its Member States.

[25] ECJ, Opinion 1/17 delivered on 30 April 2019.

[26]See, for example, Chapter 21 of the CETA. See also A. Hervé, "La loi de marché - Réflexions sur la coopération réglementaire instaurée par l'AECG", Revue des affaires européennes, n° 2, 2017, pp. 235-242.

[27]P. Lamy, " Les frontières de l'économie ", Pouvoirs, 2018, n° 165, pp. 91-87, p. 84.

[28]Reflecting what has been achieved in the context of the internal market.

[29]See European Commission, Annual Report op. cit.

[30]It is simply regrettable that this cooperation between regulatory authorities is exclusively confined, for the Union, to the European Commission services alone (Member State officials are de facto excluded from the dialogue) and, moreover, to officials in the Directorates-General for Trade and the Internal Market, to the exclusion of other Commission services that are nevertheless at the forefront of the issues dealt with (DG Health and Consumers or DG Environment, etc.)

[31]At most, competition law is reflected by the possibility of maintaining or adopting customs duties to correct illegal trade practices (in this case dumping or certain export subsidies). See B. Deffains, O. d'Ormesson and T. Perroud, Competition Policy and Industrial Policy - For a Reform of European Law, Report for the R Foundation. Schuman Foundation, Jan. 2020, p. 32 https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/doc/divers/FRS_For_a_reform_of_the_European_Competition_law-RB.pdf

[32]Information provided in the Treaties concerned and on DG Trade's website.

[33]A plurilateral negotiation involving the European Union, China, Japan and the United States was initiated at the WTO almost two years ago.

[34]Notably see article 16.4 of the CETA.

[35] These proposals made in 2019 have been made public on DG Trade's website.

[36] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, OJEU L 119, 4 May 2016. Conversely, the recently negotiated US treaties, notably the new NAFTA, admit in a much more restrictive way the possibility of restricting data transfer, including for reasons of personal data protection. See in this sense Article 19.8.3 of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

[37]See in particular article 21 of the Treaty on European Union.

[38]Article 13.1 of the EU-Vietnam Agreement.

[39]European Parliament report containing a motion for a resolution on the conclusion of the EU-Vietnam FTA, 28 January 2020, Aç-0017/2020.

[40]Article 13.3.3 of the Agreement.

[41]Article 13.3.4: "A Party shall not apply environmental and labour laws in a manner that would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between the Parties or a disguised restriction on trade. The agreement also states that "violation of fundamental principles and rights at work shall not be invoked or used as a legitimate comparative advantage, and labour standards shall not be used for protectionist trade purposes".

[42]Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention No. 98 of 1949 ratified in July 2019. However, Vietnam has not yet ratified the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention and the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention. According to the European Parliament, Vietnam has committed to ratifying these two instruments in 2020 and 2023. But this commitment is not included in the text of the trade agreement. Conversely, all EU Member States have ratified these instruments.

[43]Article 13.6 of the EU-Vietnam Agreement. The Paris Agreement is also referred to in the EU-Japan and EU-Mercosur trade agreements.

[44]Article 13.7.2 of the EU-Vietnam agreement.

[45]In 2017, the EU had already given the country a "yellow card" for its fishing practices. See the European Parliament resolution mentioned above.

[46]According to the Union, the Korean Act on Freedom of Association of 1998 excludes certain categories of workers from the right to organize. This applies to self-employed persons as well as workers who have been dismissed or are unemployed. The Union also considers that Korea is in breach of Article 13(4) 3 of the EU-South-Korea FTA, which provides that the parties shall make continuous and sustained efforts to ratify the fundamental ILO conventions. After consultations that were deemed unsuccessful in early 2019, the Union requested the establishment of an expert panel.

[47]In addition to the above report by the European Parliament, see the 2018 report of the European External Action Service on the respect of human rights and democracy in the world, which highlights in particular the increase in the number of political prisoners in that country.

[48]See Article 1 of this Agreement. The term "essential element" is important because it allows one of the parties to the agreement to suspend its application in the event of a violation.

[49]See among a broad range of literature Z. Laïdi, La Norme sans la force - L'énigme de la puissance européenne, Presses de SciencesPo, 2008, 296 p.; A. Bradford, The Brussels Effect - How the European Union Rules the World, Oxford University Press, 2020, 424 pp.

[50]Only so-called global agreements are taken into account here and not sectoral agreements (e.g. mutual recognition or customs facilitation agreements).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Earl Wang

—

13 January 2026

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :