Education and culture

Mariya Gabriel

-

Available versions :

EN

Mariya Gabriel

Disinformation, the European approach to a global phenomenon

[1] Disinformation is an attack on the freedom of opinion and expression, a fundamental right that is part of the European Union's Charter of Fundamental Rights. The freedom of expression covers the respect of the freedom and pluralism of the media, as well as the citizens' right to give their opinion and receive or communicate information or ideas "without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers." Based on this, it is the duty of public authorities to raise citizens' awareness regarding the dangers of actions that aim deliberately to manipulate their opinion, and similarly they are obliged to protect them from this.

The progression of disinformation and the seriousness of the threat it represents have been the cause of concern and of increasing awareness within civil society, as well as in the Member States and at international level. In a June 2017 resolution the European Parliament asked the Commission to analyse in depth the current situation and legal framework with regard to fake news, and to verify the possibility of legislative intervention to limit the dissemination and spreading of fake content."

The rise of platforms has gone together with a crisis in the traditional media. These offer a free, pluralist point of view of society but are suffering the effects of digitisation, which has impacted their model of financing profoundly and also the way their content is distributed.

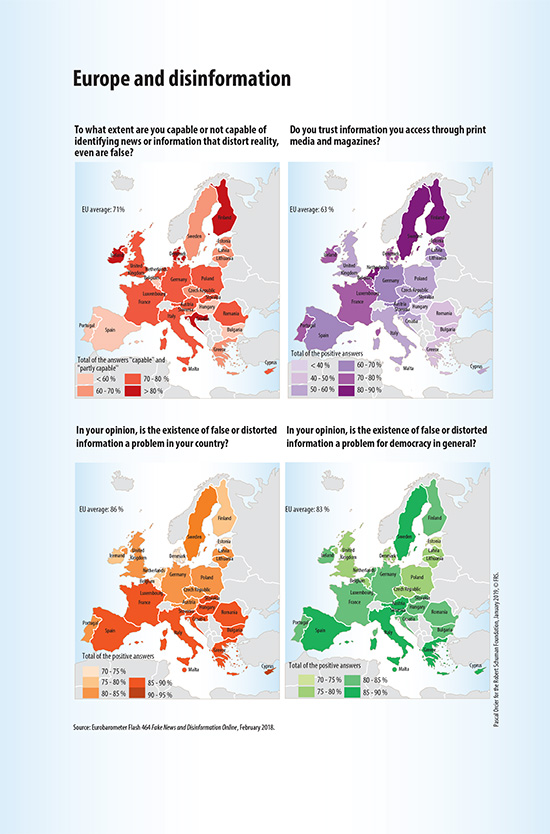

On-line disinformation is a phenomenon that is worrying all Europe. A wide public consultation organised at the beginning of 2018[2] showed that 68% of Europeans say that they encounter fake news at least once a week, whilst one third (37%) maintain they face it every day. Moreover, a wide majority of Europeans who were interviewed believe that the existence of fake news is a problem for their country and democracy in general. These results show the need for action at EU level and highlight the need to provide diverse, quality, accessible information to make the democratic process more participative and more inclusive. Figures are running high and are just examples of the extent of the phenomenon and of the speed with which disinformation has invested the media at the beginning of this, the 21st century.

A European Approach

Given an area that is void of institutional action it appeared vital to establish clear, strong markers as we began our work. This can be summarised as follows:

- Improving transparency regarding the origin of the information and the way it is disseminated.

- Promoting the diversity of information.

- Strengthening the credibility of information by providing an indication of its reliability and by improving its traceability.

- Drafting inclusive solutions to ensure the cooperation of all those involved.

On my initiative the European Commission published a Communication on tackling on-line disinformation: a European approach in April 2018. This Communication contains self-regulatory tools to counter the dissemination and impact of on-line disinformation in Europe.

The action provided for in the Communication, including a code of practice, aims to help towards protecting free, fair electoral processes, as stressed by President Juncker in his speech on the State of the Union in 2018: "I want Europeans to be able to make their political choices next May in fair, secure and transparent European elections. In our online world, the risk of interference and manipulation has never been so high. It is time to bring our election rules up to speed with the digital age to protect European democracy."

The Communication reflects our determination to improve European citizens' access to objective, quality information. It is the result of an approach that I wanted to be inclusive and therefore follows on from a multipartite consultation that provided a wealth of results, notably with recommendations on the part of a panel of high level experts that was put together to enlighten the Commission in its work.

The first success of our action was to delimit a badly defined phenomenon. Disinformation is understood as verifiably false or misleading information that is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public, and may cause public harm. Public harm comprises threats to democratic political and policy-making processes as well as public goods such as the protection of EU citizens' health, the environment or security. Disinformation does not include reporting errors, satire and parody, or clearly identified partisan news and commentary. This balanced definition, which is recognised by everyone in Europe, is now the base for our response.

The Communication identifies a series of concrete actions the main details of which I shall provide here: a self-regulatory approach for the industry: a network of fact-checkers, help for quality journalism and the raising citizens' awareness of the media (media literacy).

A code of good practice to tackle disinformation

Undeniably the self-regulatory approach desired by the Commission is the one that raises everyone's expectations, I being the first of these. It is also the one which has to produce results the fastest.

The call was heard by the main on-line platforms and the advertising sector which adopted the code of good practice to counter on-line disinformation on 26 September 2018. To date it is the most tangible result of our action in tackling on-line disinformation.

This Code is a world first: on a voluntary basis the industry commits to implementing a wide range of measures from transparency of political campaigning to the closure of fake accounts and the demonetisation of disinformation providers. Simultaneously the Code has its own inherent limits: if commitments are not respected then the European Commission will put forward other proposals including those of a legislative nature.

More specifically the Code comprises 21 commitments spread across five chapters focusing on the following areas: reducing advertising revenues from disinformation; making political advertising more transparent; addressing the issue of fake accounts and online bots, giving consumers the possibility of flagging disinformation and of having access to sources of information; giving researchers the power to monitor the dissemination and impact of online disinformation.

This code of good practice will help toward a transparent, fair, trustworthy online campaign, whilst fully respecting the fundamental principles of the freedom of expression, media freedom and pluralism.

We have received Facebook, Google, Twitter and Mozilla's individual road maps. These road maps reflect the concrete commitments of the Code of practice on disinformation as they present the measures that will be taken by the platforms to implement the commitments set out in the code of practice. These roadmaps include transparency tools for political advertising, repositories, training for political groups and electoral authorities, European electoral centres and enhanced cooperation with fact-checkers.

The Commission is now expecting the platforms to provide an initial review and will undertake a monthly follow-up of the efficacy of these roadmaps. This efficacy will notably depend on the platforms' ability to work together with fact-checkers. This is another of the commitments of the code of practice and another world first.

Increased fact-checking

The second part of our action focuses on fact-checkers. These have become a crucial factor in the current media landscape, checking and assessing the credibility of content based on facts and evidence.

Recognising their importance, we intend to encourage their work across all of Europe. In comparison with the introduction of the code, time-to-market will be significantly longer, because it is not just about adapting a few algorithms, but boosting the development of a sector that will have to cover Europe as a whole. As an example, the International Fact-Checking Network, which is the world reference in terms of the principles governing fact-checking, only includes 12 Member States.

In order to respect the independence of the fact-checkers, the Commission will not support fact- checking work directly, but it will facilitate cutting-edge technology to encourage the fact-checkers' ability to detect false information.

To this end the Commission is now financing the Horizon 2020 project SOMA, which provides an online fact-checking platform in support of their work and to increase their cooperation at European level.

However, to develop an effective response to disinformation campaigns, it is simply not enough just to check the facts. It is vital to increase our understanding of how disinformation is created and disseminated, and to assess its impact on citizens correctly.

The Commission intends to support the creation of a European multidisciplinary community via the introduction of a secure European online platform that will foster cooperation between national disinformation centres, which should coordinate all of those involved in tackling disinformation at national level, particularly independent fact-checkers and academics. The platform will offer cross-border data collection and analysis tools, as well as access to this data.

To complete this work the Horizon 2020 programme is financing other research projects designed to develop new technologies to combat disinformation, notably in the area of artificial intelligence to speed up the flagging of disinformation, interactive technologies for the media that will enable a personalised online experience and even cognitive algorithms to handle contextually-relevant information, including the accuracy and quality of data sources.

Fact-checking and quality journalism cannot be addressed in isolation. Indeed, many media do this on a daily basis, but their specific situation requires separate consideration.

In support of quality journalism

The third part addresses quality journalism. Again time-to-market is longer since we are addressing an extremely vast sector which has not yet finalised its digital transformation.

The media are vital for the communication of nuanced facts and opinions on every type of political issue; their pluralism must be guaranteed so that it represents a wide range of points of view. Facts and opinions are provided in the respect of the rights and obligations imposed by the freedom of expression and the freedom of the media, which are both European fundamental rights.

However, the traditional media are being challenged by the rise of the social media, which have rapidly eroded their market share, whether this is at reader or advertising revenue level. Indeed, advertisers prefer to place their advertising on the social media platforms than in the traditional press. The platforms offer all types of user data that can be exploited to target advertising campaigns better than the traditional media can. In particular, Facebook offers an extremely accurate targeting of various types of reader.

There is now a vast discrepancy between the size and power of these platforms' market and the biggest media companies. This situation necessarily has significant impact on the traditional media's capacity to fulfil their historic role of defender of media freedom and the public's right to information. We have to push back the limits and act, not only against disinformation, but also in support of information. Quality news must be promoted to counterbalance and dilute disinformation. Diversified, quality content is therefore vital.

The Member States must step up their support to quality journalism to guarantee a pluralist, diversified, sustainable media environment in line with rules governing State aid. If online players, the fact-checkers and the media have a role to play in addressing the problem of disinformation, it is also necessary to consider the end-user of this information, i.e. the citizen him/herself.

Educating for greater discernment

I grant particular importance to digital skills, over which there is a strong political consensus, and young people; because I am passionate about the protection and independence of our citizens in the digital world, particularly the youngest and the most vulnerable, and because I hope that each European will be able to take full advantage of the digital transition.

Thanks to improved education regarding the media Europeans will be able to identify online disinformation and to address online content with a critical eye. Undoubtedly, we find ourselves in the hardest part of our battle. In this context our initiatives will work towards encouraging fact-checkers and civil society to provide educational material to schools and educators. These, will necessarily be local and often spontaneous initiatives. In the digital age we must also ensure that the internet is a safe place particularly for the most vulnerable i.e. children. In this regard the situation is not satisfactory. More than half of young people aged 11 to 17 have been exposed to at least one type of inappropriate content.

It is in this context that I launched the #SaferInternet4EU campaign in February 2018. This campaign aims to promote the accountability of the platforms, but also to foster the education of children and provide support to parents and teachers to protect our young people better from this scourge. This campaign has had impressive reach across Europe and beyond: more than 15 million European citizens benefited from more than 1,300 new resources on themes such as false information, cyberbullying, confidentiality issues related to connected toys, exposure to harmful content or undesirable content and cyber-health.

On the whole the Communication has had a structuring effect in terms of debate and, as shown by our first report, work has progressed rapidly. However, two aspects remain undeveloped which we would now like to address: cooperation between Member States and greater consideration of aspects that are external to the European Union.

An action plan to tackle disinformation

After a first review the Communication was completed by an action plan which notably provided for the creation of an early warning system by March 2019, as well as enhanced cooperation between Member States and the Union. This plan pin points four areas of intervention:

1. Improved detection of disinformation via the creation of working groups within the European institutions, the recruitment of specialised staff and the provision of data analysis tools.

2. A coordinated response via an early warning system between the Union's institutions and the Member States to flag disinformation threats in real time and to facilitate data sharing and analyses of disinformation campaigns.

3. A rapid, effective implementation of the commitments made by the online platforms and the online services sector which have signed the code of good practice.

4. The organisation of targeted awareness-raising campaigns as well as media literacy programmes for the citizens. Particular support will be granted to multidisciplinary fact-checking teams and independent researchers in view of detecting and denouncing disinformation campaigns on the social networks.

By speaking with one voice and by showing that we stand united against the threats linked to disinformation in Europe we shall be able to arm ourselves against division, protect our democracies and guarantee free, open, fair debate for all European citizens.

Stronger Europeans for a stronger Europe

Technology is changing, but our fundamental values remain. I hope to protect Europe as a place of unity in diversity, tolerance and solidarity. A citizenship that is equipped with the necessary skills and that can listen, watch and read critically is a prior condition for the success of these values.

Our approach aims to be a global one and seeks to be both inclusive and concrete so that we can achieve a rapid reduction in the volume in false information.

I dare to believe that our work will help guarantee a transparent, open debate that will enable citizens to privilege a strong Europe in which our democratic values are and will be protected.

[1] This article was published in the "Schuman Report on Europe, State of the Union 2019" Editions Marie B, collection lignes de repères, Paris, March 2019

[2] Eurobarometer 464 Fake news and online disinformation

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

Ukraine Russia

Alain Fabre

—

11 March 2025

Gender equality

Juliette Bachschmidt

—

4 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :