Institutions

Pascale Joannin,

Eric Maurice

-

Available versions :

EN

Pascale Joannin

Eric Maurice

A notable rise in turnout

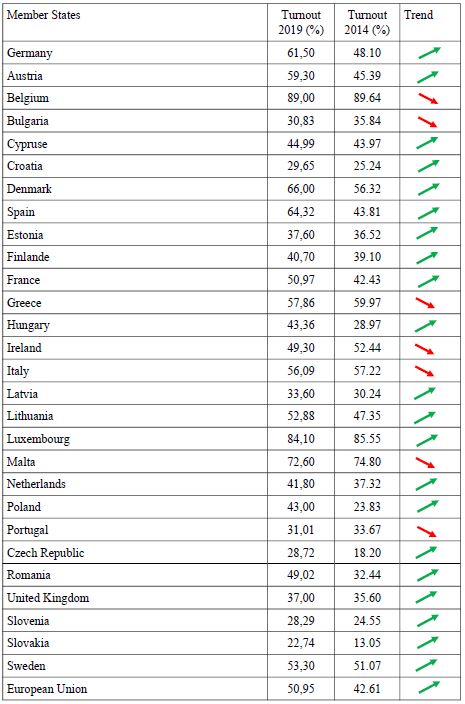

The first striking fact about these European elections is the turnout, which totalled 50.95% across the 28 Member States, up by 8.34 points in comparison with the election of 2014. It is the highest rate since the 1994 elections (56.67%, whilst at the time the Union only had 12 members). The decline in turnout, a constant since the beginning of the election of the European Parliament by directive universal suffrage, has been halted for the very first time. It is also the first time since 1994 that more than one European in two has gone to elect his European representatives.

The increase in turnout in 20 States out of 28 transcends the political and social divisions that we might have seen over the last few years, between the north and south and especially the east and west of the Union. In five countries - Germany, Austria, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia - turnout was up by around 10 points or more. In four countries - Spain, Hungary, Poland, Romania - the increase was around or over the 15-point mark.

Unlike 2014 no country recorded turnout below 20%, and it was up in all countries where it had been below 30% in 2014. If we exclude Belgium and Luxembourg, where it is obligatory to vote, turnout is not over 66% in any country.

As it rose beyond the symbolic mark of 50%, the turnout rate has lent greater democratic legitimacy to the European Parliament, in a context of widespread challenge to political powers. It also reflects the fact that increasingly European citizens deem that the questions of concern (security, migration, economy and social, climate) must find their answer at European level (see the study "Citizens' expectations regarding the European Union")

The national context in several countries, often linked to issues that cover relations with the Union, also played a role in the increased mobilisation of the electorate.

In Poland, where turnout was up by nearly 20 points, the European elections were considered a full-scale test prior to the general elections planned for the autumn, with in particular the constitution of a wide centre-centre-right coalition, called the European Coalition (KE), against the Law and Justice Party (PiS) in office.

In Romania the 17-point increase in turnout can be explained in part by the simultaneous organisation of a referendum initiated by the President, regarding the reform of the judicial system launched by the social democratic government, against which many demonstrations have been organised in the country. In these two countries, the fact that it was a national test also implied a European dimension, in that the challenge to the rule of law by both governments has placed Poland and Romania in the dock in Europe.

In Spain where turnout rose by more than 20 points, regional and local elections were also organised in some major cities like Madrid and Barcelona. The European election also confirmed the result of the parliamentary elections that took place on 28th April, which were won by the PSOE.

In France, the European elections were the first since 2017 and President Emmanuel Macron, likewise the far-right, turned it into a domestic political challenge.

To a lesser degree the vote in the Czech Republic could also be considered as a vote for or against Prime Minister Andrej Babis, suspected of embezzling European funds and who faces regular public demonstrations.

In Hungary where turnout was up by nearly 15 points, Prime Minister Viktor Orban turned these elections into a new vote on his anti-migrant policy directed against the institutions of Europe.

In the two countries most affected by Brexit, the UK and Ireland, paradoxically the issue did not lead massive citizen turnout. In the UK, whilst the Prime Minister Theresa May was on the verge of resigning due to the stalemate over the way the country should leave the Union turnout rose to 37% against 35.6% in 2014. In Ireland whose prosperity, and even its security, might be affected by Brexit turnout was down, under 50%.

By bringing the downward trend in turnout in the European elections to a halt in this spectacular manner the European Parliament can hope to consolidate its institutional and political role, notably in the face of the Member States gathered in the Council and the European Council.

The increase in turnout reflects the increased importance of European issues in the way that citizens see their place in society and the place their country holds in the world.

National factors also played an important role in the electoral campaign, in the voters' choice and in the increase in turnout. But the place of European questions in these debates especially undertaken at national level, show an increasing Europeanisation of politics in the Member States.

The end of the two-party system

As we announced in our previous studies, one of the main lessons to be learned from this European election is the end of the two-party system , in force since 1979.

The two main groups (EPP and the S&D) are still numerically the largest groups with respectively 180 and 146 seats, according European Parliament forecasts. But they are both diminished in comparison with 214 (37 fewer seats for the EPP and 41 seats for the S&D).

Indeed although many parties in the EPP group came out ahead in Germany, Ireland, Austria and Cyprus where they are in office, but also in Romania and Greece where they are not in government, other parties achieved their worst score ever, like the Republicans (LR) in France, which now only has 8 MEPs (-8) and Forza Italia (6 seats, -5), or they achieved a poor score like the People's Party (PP) in Spain (12 seats -4).

To the left only the PSOE in Spain, the PS in Portugal and the PvdA have managed to save a leading position. Everywhere else the parties on the left have failed, like the German SPD (-11 seats), the Democratic Party in Italy (_ -), the PSD in Romania (-4) and the PS in France, which had the worst score in its history (6.19%, - 5 seats)

EPP and S&D will no longer be able to form an absolute majority alone as it has been the case since the first election of MEPs by direct universal suffrage. Together they only have 326 seats, i.e. 51 less than the required majority of 376 seats.

A new pro-European majority.

Pro-European political forces are still in the majority in the Parliament, occupying 67.5% of the seats.

Apart from the EPP and S&D groups, the Parliament is home to two other groups - the Liberals (ALDE) and the Greens (Greens/EFA) with whom they will, in all likelihood, join forces to form a new majority. Especially since the Liberals have witnessed a 41 seat increase in comparison with 2014, thereby becoming the third group in the European Parliament, a place they have snatched from the Conservatives (ECR), which now only have 59 seats instead of 77, notably due to the collapse of the British Conservatives, who formed to date the main share of the group's members along with the Poles of Law and Justice (PiS), who will probably retain the chairmanship.

To a lesser degree the Greens have also a witnessed an increase of their number with 17 seats notably due to the excellent results in Germany, where they came second behind the CDU/CSU, but ahead of the SPD - which indeed is a problem to the German "grand coalition" - and in some other Member States like Belgium, Netherlands and France.

The EPP and the S&D will have to initiate negotiations with these political groups to choose to accept one or two in a new majority alliance.

Eurosceptics still divided.

The tidal wave that some had dreamed of did not occur.

Although two parties have made a major breakthrough, the Italian Lega rising from 6 MEPs in 2014 to 28, i.e. an increase of 22 seats, and the Brexit Party, which has 29 seats, i.e. a lesser progression because its leader already won in 2014 under the UKIP label, they will not sit in the same group, as is already the case in the outgoing Parliament. The Brexit Party will undoubtedly join forces again with the other Italian government coalition party, the M5S !

Divided in three groups in the outgoing Parliament between the ECR, which dominated, the EFDD and the ENF, the eurosceptic groups have not progressed as much as they would have liked, now occupying - along with the far left (GUE-NGL) 209 members i.e. 27% of the Parliament.

The three groups "weigh" approximately the same in terms of seats (ECR 59, ENF 58 and the EFDD 54)

It is very likely that their divisions will continue, even if one cannot rule out a reshuffle ,when the British have finally left the Union. But this date is still an unknown.

By then the Brexit Party will have to have a group and its leader will have to ensure the chairmanship as before. The Poles will chair the ECR without sharing this with the British and the Italians, will now be the leading force in the ENF and will take the chairmanship, without sharing it with the French National Rally which has not increased the number of its seats in comparison with 2014.

The only government led by a GUE/NGL member, ie Syriza in Greece, suffered badly as it came second with 23.74% and 6 seats (the same number as in 2014). Of course, it has improved its score in comparison with 2014 but it has emerged destabilised in the national arena where it has had to convene a snap election. Everywhere else the far-left parties are declining, whether this is Die Linke (The Left) (5.5 %) or France insoumise (France Unbowed) (6.31%).

***

The composition of the groups that will begin next week might lead to some surprises with some parties leaving the movements in which they have sat to date, to join another or to form a new one. We might of course imagine a union of the Eurosceptic forces in two parties rather than three, if their leaders can calm their egos and their desire to dominate their own space. Also, they will have to succeed in putting a programme together and define a joint political line. To be against something is not enough.

As for the major groups, we cannot rule out some change. Between those who support the continuation of the "usual left-right coalitions" bringing together the pro-Europeans, widened this time to three or four parties, or those who want to try and break these traditions and seek a new, unnatural majority. We notably think here of what the party of the Hungarian party will do in the EPP!

Negotiations will start on 28th May and will be lively between heads of State and government to find a formula that will lead to the appointment of the executives to lead the institutions (Parliament, Commission, European Council, ECB) who will have to both represent the reality of the vote expressed by the citizens, the diversity of political and territorial origins and the balance between men and women.

This exercise might prove to be a true conundrum. We cannot be sure that the established rules will all be followed to the letter in terms of finding the most balanced formula but also - we hope - the most ambitious for Europe so that we can rise to the many challenges that our continent now faces.

Click here to see more in PDF format

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :