Institutions

Eric Maurice,

Chloé Hellot,

Delphine Bougassas-Gaullier,

Magali Menneteau

-

Available versions :

EN

Eric Maurice

Chloé Hellot

Delphine Bougassas-Gaullier

Magali Menneteau

A. A Parliament undergoing controlled development

1/ Reorganisation of the political landscape

Separation of the two main groups: EPP and S&D

The politically striking feature of this legislature was the end of the "grand coalition" mid-mandate between the two main groups, the European People's Party (EPP) and the Socialists & Democrats (S&D), to which the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) were associated.

In June 2014 the three groups committed to "to work to create a stable, pro-European majority in the House to defend the values and principles of European integration whilst striving, jointly, for reforms that will strengthen and improve the workings and transparency of the institutions and their effectiveness in delivering economic growth and meeting the EU's future challenges." The EPP and the S&D agreed to share the presidency of the Parliament between the S&D for the first half of the legislature and the EPP for the second, according to the almost constant habit adhered to since 1979. With the support of three of the four main political groups, the outgoing President and unfortunate candidate for the Presidency of the Commission, Martin Schulz (S&D DE), was re-elected in the first round of voting on 1st July 2014, 409 votes out of the 612 votes cast with three candidates in the running.

The pact was broken by Gianni Pittella (S&D, IT), the group's leader, in November 2016, when he decided to stand for the presidency of Parliament to replace Martin Schulz, who left to fight in the election for the German Chancellery against Angela Merkel in the federal elections of September 2017. He accused the EPP of not respecting the agreement concluded in 2014 by refusing to allow the European Socialist Party (PES) to retain the presidency of an institution - since the presidencies of the Commission and the European Council were already occupied by the EPP. "We cannot accept the EPP's supremacy over the three institutions [...] they have not gauged the consequences of this, whilst we have shared our concern about this with them on several occasions."[2]

Guy Verhofstadt (ALDE, BE), the latter group's leader, thought of standing to bring the practice of the grand coalition to an end, going as far as envisaging an alliance with the Italian, anti-system 5 Stars Movement (M5S), which sits with the British, UKIP in the Eurosceptic group "Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD). However, he withdrew before the election, without forming an official alliance with the EPP, but negotiating a fourth position as Deputy Chair for his group, as well as the Chair of the Conference of Committee Chairs for Cecilia Wikström (ALDE, SE).

On 17th January 2017, Antonio Tajani (EPP, IT), was elected President of the Parliament 351 votes in support, 282 against and 80 abstentions. He took advantage of the political agreement between the EPP and the ALDE and the support of the group "European Conservatives and Reformists" (ECR), but he only won in the fourth round of voting, the last one being provided for by the Parliament's regulation - a unique case since 1982. Apart from Gianni Pittella four other candidates stood against him.

But a "grand coalition" in effect

The collapse of the grand coalition accentuated the politicisation of the Parliament, but only partly modified the balance between the groups. The most immediate consequence has been a decline in support by the S&D to the EPP's positions (-5% in 2017 in comparison with 2014-2016), differing however according to the issue in hand. In the year following the collapse, the grand coalition voted for example in the same direction (80/90%) on issues that came under the Budget (BUDG), Budgetary Control (CONT), Culture and Education (CULT) committees; 70% of the votes on issues raised by the Civil Liberties, Justice and Internal Affairs (LIBE) committee and 60% of those raised by the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) committee[3].

In all the EPP and the S&D found common ground in 90% of the final votes in 2017, but only in 62% of the "non-final" votes, indicating that although final positions might have drawn closer together, they were initially often quite far apart.

The grand coalition no longer officially exists, but in reality, it continues, because the institution's rationale encourages the groups towards compromise most of the time and political logic brings pro-European groups together in the face of Eurosceptic and extremist groups. Moreover, the political distribution of the chairs of the Parliamentary committees has not been influenced by the collapse in the EPP/S&D agreement. This has helped maintain the continuity of legislative work and balance in the decision-making process. The EPP and the S&D are still the two main actors in the Parliament, those which shape the decisions. In the next legislature the probable loss of the absolute majority that the two groups hold might distance them slightly more from one another. An increased alignment of positions against the Union on the other hand, would lead them to continue a necessary cooperation, so as not to block Parliament's work.

The pivotal role of the liberal group (ALDE)

The second consequence of the end of the grand coalition has been the increase in the pivotal role played by the ALDE, the fourth biggest group in numbers of MEPs. The liberal group voted like the EPP in 90.5% of the final votes in 2017. But often it joined forces with the left coalition (S&D, Greens, GUE/NGL) to tip the majority in the Constitutional Affairs Committee (AFCO), Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL), Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO), Legal Affairs (JURI) and LIBE.

The coalition of the groups on the left was effective in the politicised committees like AFCO, AGRI, CONT, EMPL, IMCO and JURI, in which the EPP was only able to form a majority in fewer than one vote in two. In all, during the year following the collapse of the grand coalition, the S&D, thanks to the left- wing coalition, which was sometimes strengthened, and the ALDE, the lynchpin party registered a higher success rate amongst the groups at 86% and 85%. Despite its position of the most powerful group in terms of numbers of MEPs and key posts, the EPP only achieved an 83% success rate. The other groups which do not have the necessary strength to form a majority without a "big" group, were only successful 65% of the time (Greens/EFA), 57% (ECR) and 29% for the "Europe of Nations and Freedom" (ENF, created with the French far right, Rassemblement National), which illustrates how little influence the biggest French delegation has (23 MEPs at the start of the legislature).

Fragmentation of the political landscape

Beyond the institutional dispute over the distribution of posts between the two main European parties, and even the personal factor - the election of the successor to Martin Schulz pitched two Italians against one another, one elected for the first time in 1994 (A. Tajani), the other having had a seat since 1999 (G. Pittella) - the break up between the EPP and the S&D also corresponded with an increasing polarisation of the European Parliament, that was accentuated by the increase in the number of political groups (8), ranging from the radical left to the far-rights and the various crises experienced by the Union, to which possible responses are the cause of marked increase in debate.

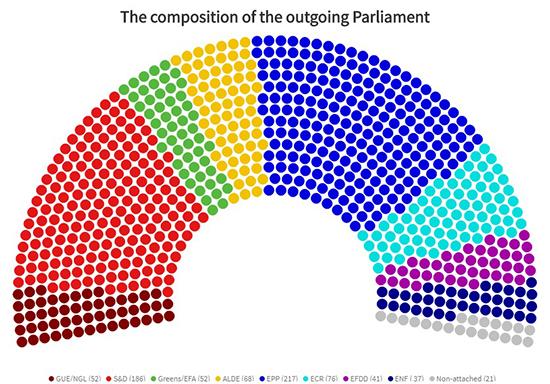

Resulting from the first election since the beginning of the euro zone crisis, the Parliament established in 2014 modified significantly political balances. Eight groups were formed during this legislature, i.e. one more than during the three previous legislatures: EPP (217 seats), S&D (186), ECR (76), ALDE (68), Greens/EFA (52), GUE/NGL (52), EFDD (41) and ENF (37). As a result, the influence of most groups in the hemicycle decreased. The EPP and the S&D represented 28.93% and 24.9% of the seats, against 35.73% and 25.52% after the last election in 2009[4]. The ALDE and the Greens, two other parties that traditionally form the core of parliamentary balance only occupied 9.07% and 7.46% of the seats, against 10.86% and 7.46% in 2009. The Eurosceptic groups however increased their influence in the 8th legislature: the conservative ECR rose from 7.46% to 10.13%, the far left GUE/NGL from 4.58% to 6.93%, and the Eurosceptic EFDD from 4.06% to 5.47%.

The increased fragmentation and weakening of the main parties, reflecting political developments in the Member States, are part of the long-term and represent one of the major challenges to be faced by the next Parliament. Its balances and ability to legislate will depend largely on the "alternative" groups' ability to organise and define coherent political lines and that of the "main" groups, deprived of a stable majority, to build alliances on both sides of the political spectrum.

An ineffective group: ENF

The development towards greater, but fragmented representation across the entire political spectrum was illustrated by the formation of the far-right group, discrete from the conservative group (ECR) and the eurosceptic group (EFDD), based on the British europhobes of UKIP and the Italian anti-system M5S.

The ENF group comprising 36 MEPs was officially formed on 16th June 2015 with the Front National led by French woman Marine Le Pen, with the Lega Nord (Italy), the Freedom Party (PVV, Netherlands), the Freedom Party (FPÖ, Austria), Vlaams Belang (Belgium), two MEPs of the Polish KNP and one Briton, previously excluded from UKIP. Above all perceived as a political instrument for Ms Le Pen, whose party represents nearly 2/3 of its members, the ENF has not satisfied its leaders' expectations. The Front National, now the National Rally (Rassemblement National - RN), is under prosecution by the French judiciary for having created fictious parliamentary assistants' jobs with a financial loss to the European Parliament estimated at 4.9 billion €; its leader left the Parliament for the French National Rally in the June elections of 2017 and several MEPs have left the party, then the ENF group following some internal crises in the RN. There are just 16 French members with seats now, against an original 23.

The lack of influence on the part of the ENF, illustrated by its low rate of success, is also reflected in a lack of political coherence, revealed by the result of the French MEPs. The latter voted against the relocation of asylum seekers and the use of the Union's budget to help countries facing a massive influx of migrants, but also against the proposals to strengthen Frontex, the European border management agency and against the creation of an entry and exit system to record data of non-Europeans entering the Union. They were against the measures put forward to organise and regulate legal immigration, but were also opposed proposals to reduce the causes of migration!

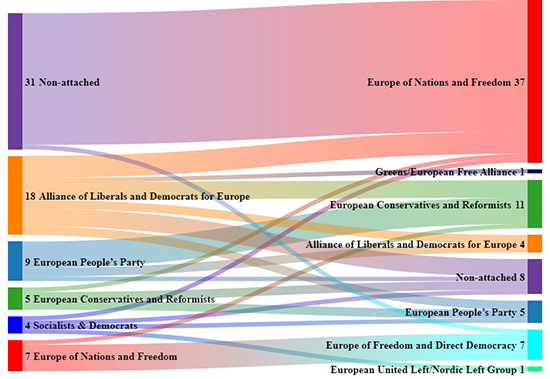

Greater Fluidity

The fragmentation into several groups following different eurosceptic, europhobic and extremist movements went together with greater fluidity, with many defections by MEPs from one group to another, depending on the trials and tribulations of party life. During the legislature 15 MEPs left the EFDD, mainly to join the ENF (5 MEPs), but also the ALDE (4) or the ECR (3). Conversely 7 MEPs joined the EFDD, 6 from the ENF, which itself lost 7 MEPs (who joined the ECR).

The EPP with 9 defections is the second group to have lost more members, mainly to the advantage of the ECR (6 MEPs). It gained 5 however: two from the ECR (2 British Conservatives!), 2 from the ALDE and 1 from the S&D!

The most stable groups were the GUE/NGL and the Greens/EFA, who did not lose any MEPs and even won one each from the S&D and the EFDD respectively.

Cohesion and participation

In effect group cohesion during the votes was lower in the EFDD (67.2%) and the ENF (79.4%). The most coherent group was the Greens/EFA (97.2%), ahead of the EPP (95.5%), the S&D (94.6%), the ALDE (92.6%), GUE/NGL (89.4%) and the ECR (86.1%). In the votes by roll call the Greens/EFA and the EPP even achieved a 98.5% cohesion rate[5].

In terms of voting turnout, the groups were relatively homogeneous in their behaviour. MEPs from the S&D, ALDE and 89.3% of the Greens/EFA participated on average in the votes. The EPP, ENF MEPs 88%, ECR 86%, EFDD 83%. The non-attached were less assiduous (81.2%)

2/ Stability of the Internal Institutions

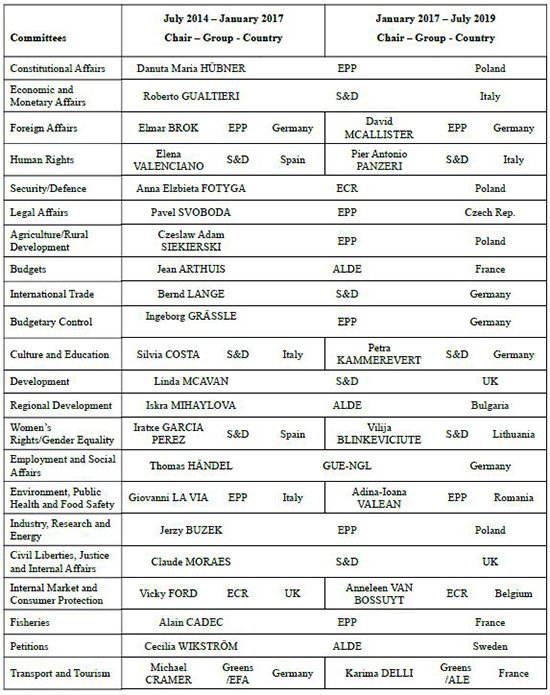

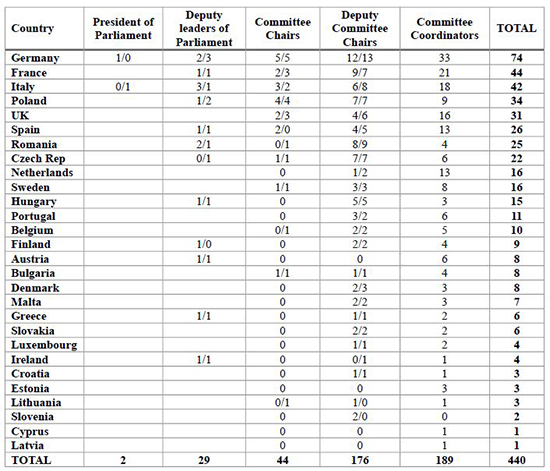

The Committees, reflection of power

Within the European Parliament the 22 permanent committees are at the centre of power, where compromises and majorities are built, and also where groups, nationalities, and even individual opinions can exercise their influence. The distribution of the committee chairs expresses the main political balances and reflects developments in the influence of the Member States within the groups and the hemicycle. Via these committees, the "central" groups have limited the effects of political reorganisation and have kept the smooth functioning of parliamentary work under control.

The EPP and the S&D have held the majority of the chairs, respectively 8 and 7 chairs out of 22, i.e. 36% and 32%. The ALDE has chaired three committees, ECR 2, GUE/NGL and the Greens/EFA 1 each. A sign on the part of the parties which support European integration of creating a "sanitary cordon" around key posts, the Eurosceptic and extremist groups have not held the chair of any of the committees, and only two deputy-chairs out of 88.

POLITICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE PERMANENT PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE CHAIRS

The Germans, still predominant

The distribution of committee chairs by nationality has illustrated the importance of German influence in the Parliament, as well as the rise of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe to the detriment of the countries in the South. Whilst the committee chairs remained in the same political camp during the entire legislature six of them changed holder mid-mandate - Foreign Affairs (AFET), Human Rights (DROI), Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI), Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO), Transport and Tourism (TRAN) Culture and Education (CULT), Women's Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM). In five of them the nationality of the chair changed, with the prestigious AFET remaining in German hands and David McAllister as its head, replacing veteran Elmar Brok.

In all Germany occupied 5 chairs during the entire legislature and Poland 4. The other major countries, including France, only held 2 or 3 chairs. Mid-mandate France gained the chair of the TRAN committee (Karima Delli, Greens/EFA) in addition to the Budget (Jean Arthuis ALDE) and Fisheries (Alain Cadec EPP) committees; Italy went from three chairs to two, but won the Presidency of the Parliament. German MEPs also occupied 12, then 13 Deputy Chairs in comparison with 9 and 7 for the French and 6 and 8 for the Italians.

The British, still influential

The UK dropped from 3 to 2 committee chairs, Development (Linda McCavan, S&D) and LIBE (Claude Moraes, S&D). During the mid-mandate renewal, the UK did however retain the chair of the IMCO committee, but it lost this when Vicky Ford (ECR) left Parliament to stand in the British general elections in June 2017.

The fact that the British, even after the vote in June 2016 in support of Brexit, kept three committee chairs, two of which are vital for the functioning of the Union and the future relation between the EU and the UK, highlights on the one hand, the often more pro-European profile of British MEPs in comparison with their national colleagues, and on the other their competence, which is often acknowledged both in Strasbourg and Brussels, as well as the aura the country has retained amongst many MEPs, particularly from countries which are open to a more liberal vision of the Union. British positions were also maintained as Committee Deputy Chair (4 in the first half of the mandate, 6 in the second part) and Coordinator level (16 during the legislature).

Geographical Shift

The major losers in the distribution of committee chairs were Spain, the Union's 5th biggest country, which dropped from having two chairs to none mid-mandate[6], and the Netherlands, a founder country, which did not win any chairs. Three countries had one chair in the first half of the legislature and 6 in the second half. None of the countries were from the South. Conversely four countries of Central and Eastern Europe, resulting from the enlargements of 2004 and 2007, held a Committee chair, two of which for the entire legislature (Czech Rep., Bulgaria).

This geographical shift also became apparent in the distribution of Deputy Chairs: 8 then 9 for Romania, 7 for the entire legislature for Poland and the Czech Republic, 4 then 5 for Hungary, against 4 then 5 for Spain, 2 for Belgium, 1 then two for the Netherlands.

At the lesser, but vital level of committee coordinator, the "old" Member States remained predominant. The coordinators are the groups' monitors, as the latter distribute roles to their representatives within the committees, particularly to lead parliamentary reports and negotiations over amendments. 33 of the 189 coordinators in this legislature were German, 21 French, 18 Italian, 16 British and 13 Spanish or Dutch.

Temporary Committees

Since 2014, the Parliament has created two committees of inquiry: the measuring of emissions in the automotive sector (EMIS), in response to the so-called 'Dieselgate' scandal; the laundering of capital, tax evasion and fraud (PANA) in the wake of the "Panama Papers" revelations.

It also created five special committees:

-Tax rulings and other similar measures by nature or effect (TAXE), introduced with the "LuxLeaks" scandal, to assess the abusive tax practices in the EU;

-Tax rulings and other similar measures by nature or effect (TAX2), to continue work on the practice of tax rulings;

-Financial crime, tax fraud and evasion (TAX3), which looked into practices like VAT fraud and citizenship programmes in exchange for money;

-Terrorism (TERR), created after the wave of attacks in 2015-2016 to assess the efficacy of anti-terrorist measures in Europe and their impact on fundamental rights;

-Union pesticide authorisation procedure (PEST), created after the Monsanto Paper revelations.

Three committees were chaired by the EPP, TAXE and TAX2 by Alain Lamassoure (France), PANA by Werner Langen (Germany); two committees were chaired by the S&D, EMIS and PEST (Kathleen van Brempt, Belgium; Eric Andrieu, France) and by ALDE, TERR and TAX3 (Nathalie Griesbeck, France; Petr Jezek, Czech Rep.).

Distribution by nationality suggests a compensatory measure for France, which is not represented a great deal amongst key posts concerning politically sensitive issues.

The committees of inquiry, whose power is based on the European Parliament's right to control, are responsible for investigating breaches of community law or allegations of poor administration in the implementation of EU law. The special committees are only there to address specific issues.

Via the PANA, TAXE, TAX2 and TAX3 committees the Parliament was able to play an active role in an issue, taxation, over which it only enjoys co-decision powers with the Council.

The President of the Commission, in his role of former Prime Minister of Luxembourg, had to appear before the PANA committee.

The conclusions of the special committees also enabled the Parliament to influence response by the Union to the tax evasion scandals. The proposals put forward by the Commission in January 2016 took up a major share of the TAXE committee's recommendations, notably the creation of a black list of tax havens.

With the inquiry committee EMIS and the special committee PEST, Parliament also addressed issues over which the Council or the Commission have traditionally held control, particularly via the intermediary of comitology, whose lack of transparency is increasingly under challenge. Both committees helped shed light on the shortcomings of the Union's homologation mechanisms. The recommendations made by the EMIS committee were taken up in the "Clean Mobility" package adopted in March 2019, and in its recommendations, the PEST committee asked the Commission to legislate on approval procedures of products such as glyphosate.

Parity slightly up

At the end of the legislature the percentage of women in the hemicycle lies at 36.4%, slightly up in comparison with the start of the mandate (35.8%)[7]. In the previous legislature 35.5% of MEPs were women. In comparison the world average lies at 23.6% and the average in the Member States is 29.8%.

Whilst the two presidents elected in 2014 and 2917 were men, women occupy five Vice-Presidencies out of 14, whilst parity has been perfect for the permanent committee chairs (11 women out of 22). In the previous Parliament three women were Deputy Chairs and 8 Committee Chairs.

As a whole the institution has not achieved the goals it set in 2017 to reach 30% of women General Managers, 35% Directors, and 40% of unit heads. Women represent 15.4% of General Managers, 30.4% of Directors and 36.2% of unit heads in Parliament. Moreover, cases of harassment, notably collated on a blog "MeTooEP" damaged the institution's image. In January 2019 MEPs rejected an amendment of the Internal Regulation calling on MEPs to abstain from any type of moral or sexual harassment and to close access to certain posts to MEPs who refused a specific training to prevent harassment; but in March they adopted a budget to introduce a mediator and a psychologist dedicated to prevention. Several MEPs, including the President of the Parliament, signed a commitment to counter this phenomenon.

B - Legislative activity as events took place

1/Rise in number of votes

In a context of deep, rapid change in the Union's economic, societal and geopolitical environment, Parliament's legislative activity was higher in this legislature than in the previous one and this despite the clear determination of the Commission to legislate better and less.

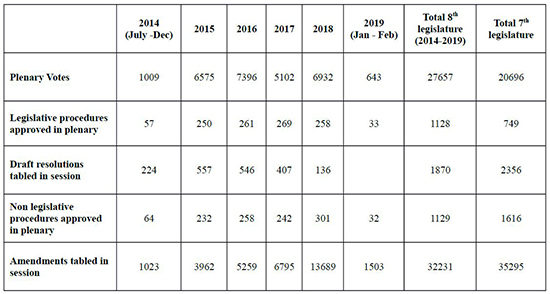

From July 2014 to February 2019 MEPs voted 27,657 times and adopted 1,128 legislative acts (in comparison with 749 between 2009-2014). The number of resolutions (1 870), of non-legislative acts (1 129) and amendments (32 231) submitted to vote is below that of the previous legislature, a sign of more concentrated parliamentary activity regarding real acts and targeted position taking, as well as preparatory work for plenary sessions, in the committees in order to "finalise" texts, with intense cooperation between rapporteurs and coordinators.

STATISTICAL REVIEW OF WORK IN PLENARY SESSION (DATA AVAILABLZ UNTIL THE FEBRUARY 2019 SESSION)

2/ Priorities and novelties

A reflection of the Commission's priorities and of measures dictated by events and more long-term developments, the Parliament's activity has mainly be devoted to the security and protection of the Union's borders, the protection of citizens and consumers, social convergence in the single market, regulation of financial activities and tax practices, energy and environmental transition and the assertion of the Union as an open but steadfast trade power.

Security and Borders

Between 2014 and 2018, 2 million migrants arrived in Europe and almost 18,000 people died or disappeared trying to get there. Following a peak in 2015 and in the face of this crisis, the EU legislated as a matter of urgency, but also in view of the long-term.

In response to the crisis, the Parliament notably adopted the creation of the European Border and Coast Guard (February 2016) and its reinforcement (April 2019), the revision of the Schengen Code (February 2017), a strengthening in the Schengen Information System (SIS) in the area of border control and the return of illegally resident third country citizens (October 2018), the revision of the mandate of the eu-LISA agency, which manages the European Union's large scale information systems (July 2018) and the creation of the European information and travel authorisation system (ETIAS) which steps up control procedures regarding visa-exempt third country citizens (July 2018). In the discussions over file management, generally the Parliament followed the Commission's proposals, whilst adding transparency guarantees and the protection of personal data.

The attacks that affected several Member States in 2015-2016 led Parliament to adopt measures to counter terrorism and radicalisation and in particular, the European register of air passenger data (PNR) in April 2016, after five years of negotiation. The text was adopted by 460 votes against 173, after the S&D won guarantees regarding the protection of personal data.

Citizen and Consumer Protection

One of the most important measures in this legislature was the general regulation on data protection (GDPR), adopted on 27th April 2016 after four years of discussion, which aims to protect all European citizens from any type of infringement of their private life and their data, whilst they create a clearer, more coherent framework for businesses. On the Parliament's request the regulation introduces the idea of user information over the use of data and consent, a right to be forgotten, as well as increased sanctions.

At the same time as the GDPR, MEPs adopted a directive on the protection of personal data as part of police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters. They introduced the definition of profiling and strengthened guarantees for people targeted by this, as well as the supervisory authorities' powers.

Social Convergence

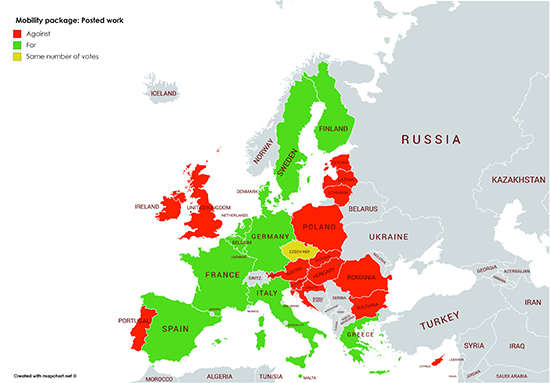

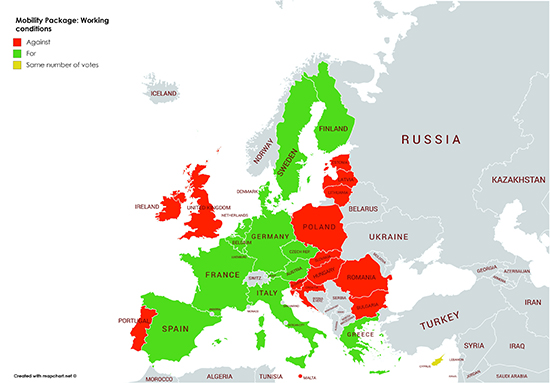

One vote captured people's attention: the adoption of the revised directive on posted workers in May 2018, which endorsed the principle of equal wages for equal work, whatever the worker's nationality. The text was the result of a long negotiation with the Member States and within the Parliament, under the guidance of Elisabeth Morin-Chartier (EPP, FR) and Agnes Jongerius (S&D, NL), which highlighted the sometimes-deep differences, between MEPs over national lines, and including within groups. The text was adopted by 456 votes against 147, with the support of five parties (EPP, S&D, ALDE, Greens/EFA and GUE/NGL), a sign of in-depth work in terms of explanation and compromise, despite the opposition of around thirty EPP MEPs from Central and Eastern Europe and also Sweden, Germany and Spain.

Parliament had to accept a limit on detachment to one year plus six months under conditions and not two years and the non-inclusion of the transport sector in the directive. However, it did achieve the application of collective agreements to detached workers and a transposition period of two years, rather than four years as demanded by the Council.

The revision of the directive was completed in April 2019 by the adoption of the Mobility Package which covers the transport sector and manages more strictly remuneration and resting time of lorry drivers, as well as the practice of cabotage, which is limited to three days.

At the end of the legislature MEPs also approved a directive regarding the balance between professional and private life of parents and carers of the sick, which harmonises paternity leave, in particular, which is now set at a minimum 10 days, as well as the creation of a European Labour Authority to counter social dumping. However, Parliament had to accept the failure of discussions in 2015 with the Council and the Commission for the extension of maternity leave to 20 weeks minimum, paid at 100%. It also failed in the last plenary session to adopt it positions regarding the amendment of the coordination of the social security systems that was contested by several Member States.

Regarding social issues, differences between nationalities often overlap traditional left-right lines, thereby making compromises difficult. This trend might be even stronger in the next legislature in a context in which nationalism and social demands will certainly make the already acute polarisation at the end of the grand coalition even more so.

Financial and Tax Regulation

The Parliament, which only enjoys consultation power, globally approved the main lines set by the Commission in the area of European tax harmonisation. Since taxation is still largely dependent on the good will of the Member States, progress remains limited apart from in the area of VAT: the digital single VAT market, a directive setting the normal minimal rate of VAT at 15%, a directive setting a reduced rate on e-publications, a regulation introducing self-liquidation VAT mechanisms and rapid response.

MEPs also approved the automatic exchange of information regarding tax decisions (October 2015) after several amendments. In November 2016 they approved a modification to the directive regarding the automatic exchange of data between Member States by asking for information regarding the fight to counter capital laundering to be integrated and made available by the Commission.

Linked to questions in the fight to counter fraud and tax evasion, the status of whistle-blowers and the framework in which they can be recognised were addressed by the Parliament. The directive on Trade Secrecy (April 2017) introduced a common definition of secret "trade" information, whilst guaranteeing the freedom of the media and the protection of their sources. A second directive (April 2019) guarantees that whistle-blowers, who flag up breaches in Union law in areas such as tax fraud, capital laundering and consumer protection, will not be the focus of reprisals. This directive was part of recommendations made by the special committees TAXE and TAX2.

Energy and Environment

During this legislature the implementation of the Paris Agreement of 2015 on the climate and the reduction of all kinds of pollution have meant intense activity in the Parliament, such as the adoption of the circular economy package to reduce waste (April 2018) and the definition of new limits on atmospheric pollutants (November 2016).

MEPs played a driving role in climate policies, particularly in the definition of energy efficiency goals. The resolution (November 2018) set the renewable energy goal at 32% by 2030 and at 32.5% the improvement of energy efficiency - thresholds higher than those suggested by the Commission (27% and 30%).

In February 2018 the amendment to the European emissions quota system was adopted (SEQE) aiming to reduce quota prices to make the market more effective, after long discussions with the Council and the Commission to limit free allowances to businesses. In November 2017 it was extended to the aviation sector. In January 2019, MEPs adopted the directive banning the use of single use plastics by 2021.

Trade

Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, Parliament has had the power to approve the international trade treaties negotiated by the Commission.

During this legislature it approved the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement with Canada (February 2017), the Economic Partnership Agreement with Japan (December 2018), as well as economic and investment protection agreements with Singapore (February 2019).

The variations in rates of approval - 71% for the trade agreement with Japan, 65% for that with Singapore and 59% for Canada[8]– reflect the degree of publicity and controversy that have surrounded the various agreements, but also the political development of the Union given the need to assert a multilateral, open order to trade in view of the challenges made by the USA since the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

At the same time Parliament adopted several measures designed to defend the Union's interests against more aggressive trade powers, particularly China. This was the case with the definition of the new anti-dumping rules (November 2017) not to grant China the status of market economy and to highlight subsidy related market distortions. In this discussion Parliament defended measures in support of SMEs and the consideration of social and environmental standards in anti-dumping measures. It was also the case with the introduction of a European foreign investment screening mechanism (February 2019), 500 votes in support, 49 against. Parliament extended the number of sectors affected by screening and stepped up the means for coordination between Member States and the Commission.

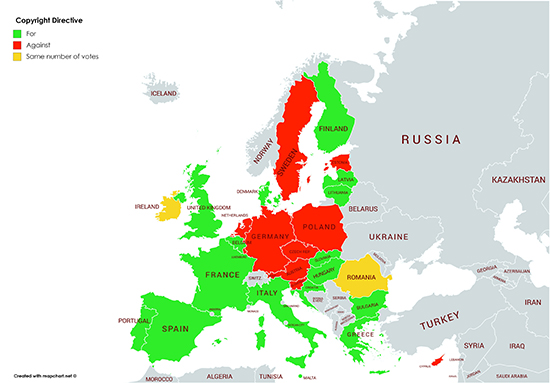

The exemplary case of copyright

In March 2019 Parliament adopted the directive on copyright, 348 votes in support, 274 against a first version of which was rejected in July 2018, 318 votes in support, 278 against. The text aims to adapt European legislation to the digital era to enable copyright holders to achieve the best remuneration agreements possible for the use of their works on the internet, whilst making digital platforms accountable for on-line content. Several types of content have been excluded from the directive to guarantee the freedom of expression, notably topical articles, parodies and criticism, and recent or small sized platforms are also exempt. Apart from the financial and societal issues that this raises, the directive was subject to several phenomenon in the Parliament, heralding its future functioning.

On the one hand, MEPs faced issues mixing traditional aspects, such as the single market and regulatory and economic impact on businesses, with new aspects such as the multiple use of on-line content or the change in use and the ecosystem of creation. The type of issue over which legislation has to be made will increase in the coming legislatures, sometimes demanding a high degree of expertise.

On the other hand, this phenomenon led to new approaches expressed by MEPs sharing a a different societal culture from many of their colleagues, like MEP Julia Reda (Greens/EFA, DE). This cultural difference, together with generation differences, should not be underestimated in term of the way that MEPs might legislate in the future.

Moreover, the directive was the focus of intense, if not aggressive lobbying, by all of those involved - artists, media, platform, user associations, free internet militants ...

For a long time, the Parliament has been the privileged place for interest groups, but this legislature has marked an additional degree in MEPs and their assistants' exposure to various actors, who do not hesitate to devote great of effort to their lobbying. This development should be the focus of specific reflection by the institution.

Finally, the geographical distribution of the votes shows extremely strong national and even regional sensitivity, regarding new issues like the regulation of the internet and the use of data, which are destined to become central to all future legislatures.

RESULT OF THE VOTE ON THE COPYRIGHT DIRECTIVE PER MEP NATIONALITY

Distribution by country or regional block transcends political leanings and the left-right split makes itself felt more or less acutely in terms of social issues. The amendment of the directive on posted workers, the result of long negotiations in Parliament and with the Member States, enabled the reduction of these geographical lines to a certain degree. Votes on the mobility package however illustrate the importance of national rather than partisan sentiment regarding issues that affect the heart of European daily life and the management of the single market in its social dimension.

RESULTS OF THE VOTE ON THE MOBILITY PACKAGE (POSTED WORK AND WORKING CONDITIONS) PER MEP NATIONALITY

C Political and institutional assertion

1/ Parliamentary regime test

"Spitzenkandidat" and political Commission

For the first time in the Union's history the President of the European Commission came directly from the Parliament, thereby establishing a new balance of power between the institutions, which Parliament hopes to assert after the 2019 election.

On the occasion of the 2014 election, Parliament, via its political groups, claimed the nomination of Jean-Claude Juncker, presented as someone being forced upon the Commission by the Member States, as they established the so-called "Spitzenkandidat" system, whereby the European parties appointed the lead candidate and that of the party, which wins the European elections to become President of the Commission.

The initiative was undertaken in the months preceding the election by outgoing President of the Parliament, Martin Schulz, based on a specific interpretation of the Lisbon Treaty. It was at the centre of the Parliament's institutional campaign on the theme "This time it's different", in which the institution insisted on the fact that it had "more power in shaping Europe than ever before."[9]

Once appointed by the European Council and elected by the Parliament on 15th July 2014, Jean-Claude Juncker lauded the assembly, "A Parliament which upholds democracy is performing a noble task", insisting on the role that the "two Community institutions" could play together[10]. In this relationship, Juncker who stated that he wanted to lead a "political Commission"[11] established its democratic legitimacy, often contested when it involved the European executive, whilst Parliament raised itself to the historic level of community institution par excellence, in the face of the Council which represents the Member States. "The European Parliament and the Commission are both Community institutions par excellence. It's therefore only right that the President of the Commission and the President of European Parliament, on the one hand, and European Parliament and the Commission on the other, should have a special working relationship with each other," stressed Jean-Claude Juncker in his first speech to Parliament. "We, Parliament and Commission, will act in the general interest, and I want us to do it together."

Hence the Commission has had a higher profile in the Parliament's work with the Commissioners attending regularly to give account and debate in the committees or by taking part themselves in the trilogues, (conciliation meetings between the three institutions to finalise legislative texts), which were traditionally handed over to the Commission's experts. In J.-C. Juncker and the Parliament's opinion, this cooperation enabled them to assert themselves in the face of the Council by creating a spirit of parliamentary regime to influence discussions between the Member States, which have sometimes been difficult due to the crises and the arrival of populists and nationalists in several national governments.

In this bid to boost the institutions, this privileged partnership notably led to the continuation of the delivery of the speech on the state of the Union, established in 2010 via the framework-agreement on relations between the Parliament and the Commission.

Thanks in part to active communication by the Commission regarding the event, the speech by the President of the Commission and the ensuing debate with MEPs, became a high point in the Union's political and institutional life during this legislature, establishing the main guidelines of the political agenda and the legislative calendar.

Debate over the future of Europe

According to the debate model on the State of the Union, in 2017 the Parliament established "Debates over the future of Europe" with the heads of State and government for them to participate in discussions, which the leaders of Europe launched in 2016, to revive the Union after the vote in support of Brexit.

Since the first debate with the Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar in January 2018 and the most recent with Arturs Krisjanis Karins (Latvia) on 17th April 2019, 20 European leaders have followed succession in Strasbourg or Brussels. Andrej Babis (Czech Republic), Dalia Grybauskaitė (Lithuania), Viktor Orban (Hungary) and Marjan Sarec (Slovenia) have not made a speech. Boïko Borissov (Bulgaria), Sebastian Kurz (Austria) and Joseph Muscat (Malta) spoke as part of the six-monthly presidency of the Council ensured by their country. For a long time, Europe's leaders have spoken to Parliament when their country started and completed the six-monthly presidency of the Council. But debate has generally been extremely formatted.

Debate over the future of Europe corresponds to another kind of dialogue between national leaders and MEPs, which is more established in topical and even confrontational politics and this has occurred several times in this legislature.

On 8th July 2015, three days after the Greek referendum rejecting the terms of the new aid plan, and whilst Greece was on the brink of exiting the euro, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras took part in a lively debate in Strasbourg which lasted nearly five hours, with MEPs. Some months earlier in May 2015, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban came to a debate at the Parliament over the rule of law in his country - he came back twice for confrontation on the same theme. Polish Prime Minister, Beata Szydlo, came to debate with MEPs over the rule of law in her country in January 2016.

Several debates regarding the future of Europe - particularly with French President Emmanuel Macron, Romanian Prime minister Viorica Dancila and the President of the Italian Council Giuseppe Conte - also led to lively exchange.

It remains to be seen during the next legislature whether Parliament will be able to continue this practice of exchange or confrontation, with the leaders of Europe and thereby assert its aim to extend the spirit of parliamentary regime to its relations with the Council.

The question of trying to impose the Spitzenkandidat on a reticent Council, as well as the personality of the next President of the Commission, will be decisive factors for the future role to be played by the Parliament within the institutional trio.

The debates over the future of Europe have also been a part of a more institutional approach after the vote on Brexit. In November 2017 Parliament published a report entitled "The Future of Europe: the Parliament sets out its vision"[12] in order to guide discussions launched by the heads of State and government. Between December 2016 and February 2017 Parliament adopted three reports on "possible developments and adaptations to the present structure of the European Union" (Guy Verhofstadt, ALDE, BE), "the improvement of the functioning of the European Union using the potential of the Lisbon Treaty" (Mercedes Bresso, S&D, ES and Elmar Brok, EPP, DE), and a "budgetary capability of the euro zone" (Reimer Böge, EPP, DE and Pervenche Berès, S&D, FR).

The Parliament has insisted on asserting its political role and its institutional place in the existential debate created by the UK's decision to leave the EU. Even if it did not take direct part in the negotiation under article 50, it was fully integrated into the measure introduced by the Union, via the intermediary of a steering group led by Guy Verhofstadt. Parliament which had to ratify the agreement with the UK, was able to use this vital role as support to dispatch political messages both to the Member States and to the UK regarding what would be acceptable or not, particularly regarding citizens' rights.

Monitoring of the rule of law

Whilst the question of infringements of democracy and of the rule of law was the centre of questions regarding the future of the Union threatened by internally opposite forces, Parliament stood as the defender of fundamental values. During this legislature MEPs adopted 11 resolutions regarding five countries: Hungary (4 resolutions in 2015, 2017 and 2018), Poland (4 in 2016, 2017 and 2018), Malta (2 in 2017 and 2019), Romania (1 in 2018) and Slovakia (1 in 2019, also regarding Malte).

Twice, regarding Hungary in May 2017, then Poland in November 2017, MEPs asked the LIBE committee to prepare a reasoned proposal to ask the Council to trigger article 7 of the TEU regarding "serious breaches" of the Union's values. In September 2018, for the very first time, Parliament, in a resolution adopted by 2/3 of those voting, decided to take an additional step and formally invited the Council "to establish whether there was a clear risk of a serious breach in the Union's values" in Hungary. At the end of 2017 it was the Commission which decided to launch the procedure against Poland.

Referral to the Court by the Parliament regarding the situations in Hungary and Poland gave rise to four debates with the heads of government, which were the only occasions during which leaders had to explain publicly in the European arena, the reforms started in their country's civil service or legal system, as well as their actions against the media and NGOs.

The Parliament also referred to topical events to link the state of the rule of law in the Member States to other issues over which the Council is impotent more often than not. In its first resolution regarding Malta (November 2017), adopted one month after the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, Parliament asked the Commission to check on the implementation and respect of the anti-laundering directives. In the second resolution (March 2019), also regarding Slovakia where another investigative journalist, Jan Kuciak was assassinated in 2018 Parliament asked the Commission and the European anti-fraud Office (OLAF) to "undertake in-depth investigations" into affairs of fraud and corruption.

The determination and ability of the Parliament to continue monitoring the Member States' practices in a likely context of polarisation and increased fragmentation will be marker of the strength of the political and institutional strength expressed during the entire legislature.

Institutional Consolidation

Signed in April 2016 by Parliament, the Commission and the Council the "Better Law-Making" agreement increased Parliament's rights and stipulates that the "European Parliament" and the Council, in their capacity as "co-legislators must exercise their powers on equal footing"[13]. In virtue of the text the three institutions must agree on the Union's annual and multi-annual priorities. The first "common declaration on the Union's common legislative priorities" was signed on 16th December 2016.

In the negotiation led by Guy Verhofstadt, Parliament succeeded in ensuring that it would be consulted before and not after the Commission elaborates its annual working programme, as well as being consulted when the Commission plans to withdraw a legislative proposal or when the Council wants to modify a legal base during an ongoing legislative procedure.

The Parliament succeeded in achieving systematic access to meetings between the Commission's officials and national experts. Apart from the fact that it will - along with the Council - have access to impact studies undertaken by the Commission, the Parliament, as well as the Council, it can undertake its own studies on the impact of "substantial modifications" brought to the Commission's proposals.

In a report regarding the implementation of the agreement (May 2018), Parliament deemed that progress still had to be made on several points, such as in the sharing of information during the negotiations and conclusion of international agreements, information from the Council and the more technical issue of the definition of non-binding criteria for the framing of delegated and implementing acts.

The question of delegated and implementing acts, which is extremely technical, was the centre of regular stand-offs with the Commission and the Council, because it defines the responsibilities in the implementation of legislative acts. Whilst implementing acts can be taken by the Commission or the Council after consultation between the two institutions, delegated acts can only be taken by the Commission on the basis of a delegation provided in a legislative act. They cannot modify the vital details of the legislative act and can be subject to the assessment of Parliament, which can object or revoke the delegation.

The Parliaments ability to privilege delegated acts is therefore a long-term issue for the assertion of its power beyond co-decision and will be a marker of its institutional claim in the upcoming legislatures.

***

Whilst it announced that it was at the beginning of a new phase launched by the Lisbon Treaty, this Parliament might in reality have been one of transition, heralding a new, but developing situation.

The first factor in this situation, which is still uncertain at a time when MEPs are completing their mandate, is the composition of the Parliament itself. The European elections (23rd and 26th May) were originally designed to appoint 705 MEPs instead of 751, due to the exit from the Union by the UK, normally on 29th March 2019. The extension of Brexit until 31st October during the extraordinary European Council on 10th April means that except if there is a political development, 751 MPs including 73 Britons will be sitting in the new Parliament as of 1st July. Since the hypotheses of an additional extension and even a cancellation of Brexit has not yet been ruled out, the duration British MEPs time in parliament will have consequences that are difficult to assess in terms of the political and geographical balances in the hemicycle.

Whatever the composition of Parliament the main issue will be to guarantee the smooth functioning and effectiveness of legislative work in the context now forecast, regarding the decline of the parties which have structured Parliament (EPP and S&D) to date, and the possible rise of nationalist parties, which are hostile to the Union as it has been built to date. The ability of the nationalists, like those of the Italian Liga, and of the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS) or the French National Rally (RN) to overcome their differences regarding migration, economic and social policy and Foreign Affairs in order to form a strong group will be a decisive factor.

The third factor is the way that the president of the Commission will be elected and the political relationship he wants to have with the Parliament. Since the European Council has clearly expressed its reticence to follow the principle of the "Spitzenkandidat" a second time, Parliament might be obliged - as soon as it is established - to endure tension between the institutions and will, in all events, have to ensure cooperation with the Commission as close as it has been under the presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker.

Finally, Parliament will probably have to legislate and debate increasingly complicated and sometime controversial issues - and sometimes it will be subject to the urgency of the situation. This work will have to be accomplished by MEPs as effectively and as openly as possible so that by the end of the next legislature the Parliament can ensure the foundation of its existence, its political and institutional influence, is embodied by the participation of its citizens in the European elections.

[1]Luuk van Middelaar, Alarums and Excursions: Improvising Politics on the European Stage, Agenda Publishing, 2019

[2]"It was the right which caused the crisis" in the European Parliament, accuses Gianni Pittella La Libre Belgique, 2nd December 2016,

[3]Source European Parliament

[4]Source European Parliament, https://election-results.eu/european-results/2014-2019/outgoing-parliament/

[5]Source European Parliament

[6]See Charles de Marcilly, European Parliament : redistribution of political balance, European Issue n°420, https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-420-en.pdf

[7]Source European Parliament, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20190226STO28804/women-in-the-european-parliament-infographics

[8]Source VoteWatch

[9]European Parliament website, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/eu-affairs/20130905STO18723/the-power-to-decide-what-happens-in-europe

[10]J/-C. Juncker, New Start for Europe, opening speech at the European Parliament plenary session, Strasbourg, 15th July 2014, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-14-567_en.htm

[11]See Sophia Russack, Institutional Rebalancing: the 'Political' Commission, CEPS, March 2019, https://bit.ly/2I81i9K

[12]Future of Europe: European Parliament sets out its vision, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/resources/library/media/20171023RES86651/20171023RES86651.pdf

[13]Interinstitutional agreement between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission "Better Law-Making", https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/fr/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2016:123:FULL&from=EN

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :