Future and outlook

Pascale Joannin

-

Available versions :

EN

Pascale Joannin

Just as the congresses of the European political parties are about to start (EPP on 7th and 8th November, ALDE from 8th to 10th November, the Greens from 23rd to 25th November, the PES on 7th and 8th December), which is the first stage in this campaign, it is now possible, using several ideas as a base to get a better idea of what is at stake in these elections.

Indeed, many wonder about the results of the vote. Some are anticipating a rise in populist or nationalist extremes, even imagining that the latter might win a majority. Others are worried about interference on the part of foreign powers in this election, which does not stir the European electorate to any great degree. Finally, others, notably in France, where it will be the first electoral event since the election of Emmanuel Macron in May 2017, as the leader of a movement that claims to be neither right nor left-wing - or rather both right and left-wing - wonder how his movement "En Marche" will fare in the European arena.

Many questions are being asked about the political recomposition and upheaval on-going within our liberal democracies. How will things turn out in Europe in May 2019?

Definitive changes

Two changes are definitely going to happen: the British will leave and the number of MEPs will be reduced.

The departure of the British

Uncertainty still surrounds the way that the negotiations with the UK will be concluded - or not, but we can take it for granted that this country's exit from the Union, the famous "Brexit", which everyone is talking of right now, without it having yet taken place, will happen, as provided by the treaties within the two years of the British having officially triggered article 50 of the TEU. This happened on 29th March 2017; and so, it will be done on 29th March 2019.

Hence, the British will no longer have any MEPs or Commissioners. They will no longer have seats in the European institutions, including during the transition period, which for the time being is planned to go on until 31st December 2020 regarding the negotiations of the future relationship with the European Union.

And so there will be no more British MEPs in the Parliament in Strasbourg. This will mainly affect three of the present political groups: the S&D group (Socialists and Democrats 187 members) who will lose 20 MEPs from the Labour Party who sit amongst its ranks; the ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists, 73 members), which will no longer include the 19 MPs from the Conservative Party and finally the EFDD (Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy, 43 members) which will lose 19 MPs from UKIP (UK Independence Party). The Greens will also lose 6 MEPs.

The departure of the British will automatically lead to an initial political reshuffle.

At this point in time, and without prejudging any potential post-election shifts, the EFDD group, without UKIP (which in the shape of Nigel Farage chairs the group) will fall short of the eligibility criteria (25 MPs from 7 Member States) with a number of MEPs below this threshold (24).

Similarly, the ECR group will lose its main delegation and its British co-chair, Syed Kamall. This group was created by the British Conservatives in 2009 and is co-chaired by a Pole from the party of Law and Justice (PiS) - which forms the second biggest delegation with 18 members. But will it retain its reason for being after the departure of its creator?

Finally, the S&D group, firstly affected by the departure of 20 Labour MPs, will also suffer due to a weaker representation of party members (German SPD, French PS, Dutch PvdA) whose results in the national elections have illustrated significant decline. This numerical decline of the S&D will affect the formation of a majority in the European Parliament.

Fewer MEPs

In 2019, the European Parliament will comprise fewer MEPs (705) than at present (751) due to the departure of 73 British members.

The number of 73 MEPs should have been subtracted from the 751, as provided by article 14, paragraph 2 of the TEU. The European Parliament's Constitutional Affairs Committee (AFCO), which was responsible for this issue looked into several possibilities, including the introduction of a transnational list, which was rejected. But initiatives hope however to push the idea in 2019.

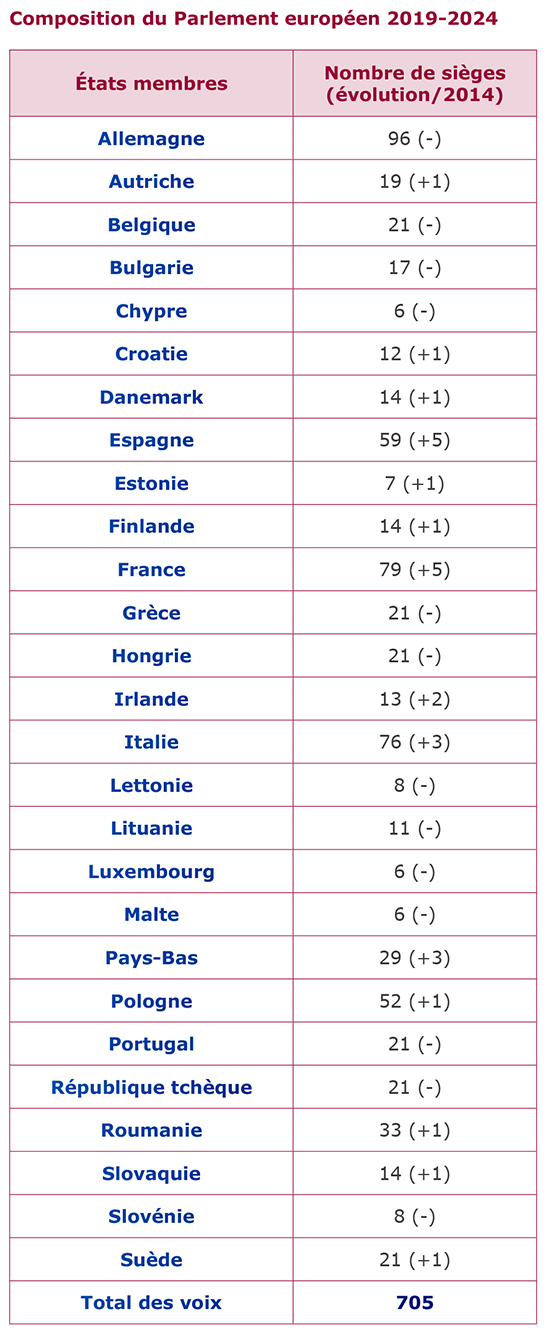

To take on board the demographic change and as a result, the weaker representation of some Member States, it was decided (Parliament on 13th June, European Council on 28th June) to redistribute a share of the 73 British seats to 14 States: France[1] and Spain (+5), Italy and the Netherlands (+3), Ireland (+2), Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Poland Romania, Slovakia and Sweden (+1), i.e. 27 seats. This aimed to better fulfil the principle of "degressive proportionality".

This distribution key is based on the principle that the relation between the size of the population and the Member State and the number of representatives in the European Parliament increases according to the size of the population. However, with a minimum of 6 MEPs for the least populous States (Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus in 2019) and a maximum of 96 for the most populous (Germany), the distribution of seats is only an imperfect reflection of the population of each Member State, since an MEP elected from one of the six most populous States represents around 800,000 of his/her fellow countrymen, against 500,000 for an intermediary sized country like Greece, 350,000 for Ireland and around 70, 000 for the least populous, such as Luxembourg or Malta. Hence, the ratio varies from one to 12.

The number of MEPs that the Europeans will be elected in May 2019 will therefore total 705 according to the following geographic distribution:

This will still not provide fair representation for all citizens. But the process to achieve this requires in depth reform, for which not all of the Member States seem to be ready.

Probable developments

Electoral turnout.

Since the election of the Members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage in 1979 participation in the European election has constantly decline. On average it was higher than 50% from 1979 (61.99%) to 1994 (56.61%). It was still close to 50% in 1999 (49.51%). Since then it has been below 50%, dropping from 45.7% in 2004 to 42.61% in 2014.

A more detailed analysis of the results by Member State reveals a major contrast. In most countries where it is obligatory to vote, the turnout rate is high, as for example in Belgium with 91.36% in 1979 and 89.4% in 2014. But also in Luxembourg (85.55% in 2014) and Malta (74.8% in 2014). However, Greece has witnessed its turnout decline to 59.97% in 2014, whilst it totalled 81.48% on its accession in 1981. The decline in turnout has been faster in Cyprus, dropping from 72.5% (2004) to 43.97% (2014) over the last ten years. However, the enthusiasm for the first post-accession elections has to be put into perspective since turnout has increased by nearly 10 points in Sweden since 1995, rising from 41.63% to 51.07% in 2014.

In the enlargement countries of 2004 - Cyprus and Malta apart - the European election has never experienced high turnout. It has remained - and by a wide margin, below 50% everywhere, (18.2% in the Czech Republic in 2014 and 13.05% in Slovakia). In these countries, which were deprived of free elections for a long time, the fact of belonging to the EU has not been a source of enthusiasm in terms of the European electoral duty, after clear, mass votes in the referendums in support of membership.

This lack of enthusiasm, to be found in the Netherlands (37.32% in 2014) and in France (42.43%), which are two founding States, or in Portugal (33.67%), and even Spain (43.81%), can be explained for two reasons.

Voting takes place in a national, and not a European context, and because of this, it is often reduced to mainly, if not exclusively, national considerations. The electorate votes according to the national political situation, without caring whether their vote will have any impact at European level or that it will be a "useful vote". Hence, this is how it was in France in 2014, which sent the biggest delegation (24 MEPs) from the Front National to sit in the political group comprising the fewest MEPs (Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF), 34 MEPs) in the European Parliament.

Similarly, the national parties often still campaign nationally without explaining to the electorate the true legislative issues and without making any references to the European political party to which they are affiliated.

The proportional voting method - which is applied in all of the States for the European elections, makes the results even harder to interpret. Indeed, no party has been able to hold or has ever held the majority since 1979. Coalitions are vital. Natural in many countries with parliamentary traditions, it is still strange for some and especially when it comes to the "grand coalition."

How can we explain that the "right and the left" are going to come together at European level, which has always been the case - except for once[2] - since 1979, whilst in the Member States they oppose each other. This is why the presidency of the newly elected assembly is not entirely attributed for the 5-year legislature, but shared between the two parties, which come out ahead (EPP and S&D), each for half of the term (2 and a half years). The present President Antonio Tajani (IT, EPP) took over from Martin Schulz (DE, S&D) in January 2017. Finally, the European Parliament, whatever one might say, does not seem to have convinced the citizens of Europe of its representativeness, in the same way that the national assemblies do.

Some hope that the international context and the challenges that Europe faces right now will encourage a rise in electoral turnout. This time round there will be good reason to strengthen the only institution in the Union to be elected by direct universal suffrage and to go and vote. Citizens and even governments are starting to organise themselves with this in view. Initiatives are now emerging to encourage electoral turnout. Will it be enough to bring the long-term trend to an end?

The progression of the nationalists

In these European elections an historic breakthrough by the extremists, populists and nationalists has been forecast, with the latter not being by nature extremely in favour of Europe, their victory has already been announced for May 2019. However, this is a somewhat hasty analysis and illustrates poor knowledge of the European election method.

Indeed, we must be careful with the designation "extremist, populist" which masks a multi-facetted reality. Indeed, in the European Parliament there is a far left-wing group (GUE/NGL, 51 members) which is not made up just of parties from the far left like for example the Greek Communists (KKE). These divisions are not likely to disappear in 2019. Since its accession to office in Greece, the Radical Left-wing Coalition (SYRIZA), for example, has won itself several arch enemies in this group and rivalries are growing. It is harder however to assess the "far right" which does not just sit in one group alone. With the Rassemblement National (RN, France) and the Party for Freedom (PVV, Netherlands) which co-chairs it, the ENF rallies parties, some of whom are now members of their national governments, such as for example the FPÖ in Austria and La Lega in Italy. Although Matteo Salvini and Martine Le Pen seem to have decided to renew their alliance, it will not occur in the same configuration. La Lega, which only has six seats at present, might gain more and its political line might be deeply changed by this.

The representatives of other "extremist, populist or nationalist" parties sit in groups that reject these definitions, such as for example the Swedish Democrats and the True Finns, who sit with the ECR.

The movement Cinque Stelle (M5S) that is allied in the Italian government with La Lega sits in another group (EFDD) of which it might take the chair due to the departure of the British UKIP. As surprising as it might seem, MS5 is not planning to sit in the same group as La Lega, its partner in the Italian government after 2019! Finally, other political movements do not belong to any parliamentary group, like the Hungarian Jobbik, deemed to be disreputable.

This fragmentation highlights the difficulty these eurosceptic parties will have if they wanted to join forces under the same banner and form just one group in the European Parliament after the next elections.

Apart from their aversion to Europe, which is their only common point, they agree on very little more, including immigration. Although they all denounce it, they are divided regarding the solutions to provide. Matteo Salvini hopes that other Member States will accept the distribution of migrants, including Italy, which in his opinion is the only one to be bearing the weight of it. Viktor Orban, who sits on the EPP, is far from sharing this vision and wants to host none, just like the Slovakian socialist, the Czech liberal and the Polish conservative! Likewise, within the ENF it is not certain that all of the parties share the same position.

Therefore, it would be very simplistic to say that the "extremes, populists and nationalists" are going to win in May 2019. Undoubtedly, they will gain ground if the results that they have won recently at national level are confirmed. But it is highly likely that they will remain divided in several groups. Apart from the fact they all want to protect their own private corner (the Poles of the PiS the ECR, La Lega its group and MS5 its own one), they will hesitate before joining other "anti-system" movements with characteristics that are so different. Finally, their overall progress will remain at the end limited. Those of the parties from the big countries, like Italy will probably record the greatest gains in comparison with 2014. In most of the other Member States their wins in terms of seats will be fewer and the same national specificities will remain, thereby making rapprochement difficult. There remains the case of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) whose 7 MEPs from 2014 sit in three different groups and only one of whom still bears the AfD label!

A reform made necessary

A new majority

Since 1979 two parties have been enough to achieve a majority in the European Parliament and therefore to organise the joint election of its president and the distribution of other posts within the EP. This majority has also been a reference point for the distribution of major responsibilities within the common institutions (European Council, Commission, High Representative, etc.) This period now seems to be over. The two main groups in the European Parliament (EPP and S&D) will no longer be able to form a majority alone.

The S&D group, which has 187 seats will suffer major decline, since it will be losing its British contingent (-20), which will not be the case in the EPP, abandoned by the British in 2009. In the S&D the main parties have almost all experienced setbacks in the most recent national elections. In Sweden, Latvia and Luxembourg elections have not yet led to the formation of a government. But in Sweden (SAP, 28.4%) as in Luxembourg (POSL/LASP 17.6%), their scores were the weakest in their entire history. This low result also goes for the German SPD, which achieved its worst score since 1949 in the federal elections of September 2017, with 20.5%. As for the French PS, it literally collapsed during the presidential election in 2017 (6.36%) and the general elections that followed (5.69%). The Italian Democratic Party came second behind the MS5, ahead of La Lega with 18.72% in the parliamentary elections of March 2018, but it is now struggling. We should recall that it won 40.86% during the European elections in 2014 and that it was the group's leading delegation with 31 MEPs. The name of the group became S&D in 2009 in order to integrate it and to prevent its fragmentation between the two groups as in the legislature of 2004-2009. What will it do in 2019? Some speak of a new scission or its departure from the group to form a new alliance with other movements like En Marche.

The socialists govern right now in Spain (without a majority), Romania (in coalition), Portugal (without arriving ahead in the national election in 2015), Slovakia (a multi-party coalition), Lithuania and Malta, i.e. six countries. The situation in Sweden is still uncertain as this article is being written.

If we are to believe the most recent polls, most of the parties comprising the S&D are forecast to achieve a score much lower in 2019 than in 2014. The first forecasts suggest a loss of around 50 seats, i.e. a final number of around 137 MEPs.

Within the EPP, the main political group in the European Parliament with 219 MEPs, the losses will not be as high but it is due to drop below the 200 MEP mark. Indeed, the party only governs in 7 countries (Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Ireland, Hungary). Moreover, the main parties that make it up are declining, starting with the CDU/CSU - which forms the biggest contingent with 34 MEPs, and which chairs the group. It won 33% in the German general elections in September 2017, but is credited with just 25% of voting intentions. The Polish Civic Platform (PO) won 31.34% and 19 seats in 2014 (Jacek Saryusz Wolski has since been excluded from the group) but it lost the power after the general elections in 2015 in Poland. It is still credited with 27%. The French Republicans did not qualify for the 2nd round of the presidential election in 2017 for the first time in their history and are credited with just 14% in the European election (20.7% in 2014). The Spanish People's Party was ousted from power in June last. Credited with 22%, it is running just behind the PSOE (24%), but it is now being challenged by Ciudadanos (21%). It won 26% in 2014. Forza Italia is not due to rise above 10%, in contrast with 16.77% in 2014.

If these trends are confirmed all of the EPP's main delegations will witness a decline in their numbers in comparison with 2014. As a result, the numerical strength of the EPP might be reduced by around 40 seats and be limited to around 180 MEPs.

Undoubtedly this is one of the reasons why some EPP members want to open the party up to other right-wing movements (non-Christian Democrats). Some have spoken of the Polish PiS. But the violence with which this party has dealt with the members of the PO, who are EPP members, banishes all idea that these two parties might sit together in the same group. The arrival of one would surely lead to the departure of the other. Moreover, it cannot be certain that the PiS would want to join the EPP group, whilst it might pretend to chair the fate of the ECR group alone. Finally and for a long time the EPP has defended championed values which do not really correspond to the PiS and challenged by the Orban case, it might not want to add one political problem to another.

Others, notably in Italy imagined that La Lega, which has already governed with Silvio Berlusconi when the latter was President of the Council, might want to integrate the EPP. Matteo Salvini has stood with Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, who is an EPP member, but also with Marine Le Pen, in denouncing European policy - largely led by the EPP - with which he is planning a joint electoral campaign. The Italian right feels quite abandoned and the polls, in which La Lega is now riding high, is causing it a real headache.

These calculations reflect the disarray amongst part of the right-wing, which is trying to compensate for the announced decline in the numbers of its parliamentary group. It is for the same reason that the EPP has kept the Hungarian Civic Union (FIDESZ) within its fold. Having won the elections for the third time running in April last with 48.53% of the vote, its delegation might be one of the rare ones to see an increase in the number of its elected representatives (11 MEPs at present). The European Parliament spoke on 12th September last in support of the launch of the article 7 procedure regarding the infringement of European values by Hungary, 448 votes in support (of which 146 were from the EPP), 197 against and 48 abstentions (of which 58 were from the EPP). The MEPs in the EPP group therefore voted in their majority in support of the triggering of this procedure. However, it would seem that in spite of the turpitude of its turbulent Hungarian member, the EPP is not planning to exclude it because the only real opposition to it in Hungary is Jobbik, a truly far right party. This attitude might confuse the legibility of the EPP's political line and disturb voters for whom the issue of the respect of the rule of law, freedom and values is primordial.

The most recent forecasts suggest 180 seats for the EPP and 137 for the S&D, and these two main parties with 317 seats will no longer hold the absolute majority (353) in the European Parliament.

The New Situation

This unusual situation will therefore lead to a more open political negotiation to find a compromise with other partners. Who might take this role?

The Greens have witnessed an improvement in their results quite recently in the local elections in Belgium, in the German Länder of Bavaria and Hessen and during the legislative elections in Luxembourg (the only party in the outgoing government coalition to win any seats (+ 3)). They can reasonably expect to have more weight in the European Parliament. They have 52 seats at present. However, present forecasts suggest they will lose 9 seats (of which 6 are British). They would therefore bring quite the minimum required number of votes to form a majority ... which is very risky.

More plausible is the scenario of a coalition with the Liberals. Firstly because the latter already took part in the majority between 1999-2004 and also because, following the departure of the British (which will not affect them very much, they only have one MEP), they could become the third biggest group in numbers of seats after 2019, since the ECR will probably fall below the 50 seat mark due to the loss of 19 British MEPs.

The liberal group has 68 seats in the present Parliament. It could draw close to the hundred seat mark if it succeeds in federating more widely than today. The Alliance of Liberals and Democrats (ALDE) is made up of two parties: the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), and the European Democratic Party (EDP). Seven prime ministers come from its ranks (the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Estonia and Luxembourg). It comprises 8 Spanish MEPs including Ciudadanos, 7 Frenchmen including Modem and the UDI, 4 Germans from the FDP and the Freie Wähler. If Cuidadanos succeeds in achieving the score predicted by the polls (21%), it might become the group's lead delegation, unless the group attracts the Italian Democratic Party. En Marche might also decide to join it. This is a question that intrigues European circles. Where does it lie in the European arena? The most recent polls forecast that this party will lead in the French results (21.5%) and the outcome of the election will greatly depend on the French domestic situation and on the popularity of Emmanuel Macron.

Many wonder about Emmanuel Macron's strategy, as he openly campaigns for Europe and as Viktor Orban and Matteo Salvini have designated him as "the enemy number one" simultaneously. If he manages to win on 26th May in France, he might emerge as one the main winner of this election, weighing over the majority and by taking part in the distribution of major responsibilities within the common institutions.

A process to be reshuffled

In 2014, in a bid to counter the disaffection of the electorate in the European election, Brussels came up with the idea of the "Spitzenkandidat", which no one tried to translate into one of the 24 Union languages so that it would be understood by voters to whom he was to address himself. First mistake. Europe is not only German speaking!

The concept provides that Europe's political parties put forward a candidate who will bear the party's colours after an internal selection process. In the event of victory, he would be appointed as the President of the European Commission. This was supposed to encourage voters to turn out because they would be appointing - indirectly of course - the future President of the European Commission. It was not really a success since the 2014 turnout was lowest ever recorded in the European elections. The parties then appointed well-known personalities: Jean-Claude Juncker for the EPP, Martin Schulz for the S&D, Alexis Tsipras for the GUE/NGL, Guy Verhofstadt for the ALDE and the José Bové-Ska Keller tandem for the Green/EFA group. Second mistake: Europe is not just made up of men!

These candidates mainly campaigned in their own countries. Of course, there were some debates but not enough, and they did not weigh naturally in the public debate due to a lack of media coverage. In which language would they have done this anyway? Would they have been understood via the existing means of translation? Third mistake: there are no real European campaigns yet because there is no European public area.

The process ended with the appointment of Jean-Claude Juncker at the head of the European Commission. However, in virtue of the sharing of power between the two main parties, the challenger S&D Martin Schulz was given the presidency of the European Parliament of which he was already the head (this renewal had never be occurred since 1979). This did not help to make the process legible for the greater part of the electorate since both men were given one of the portfolios that were up for the bidding. Many suppose that it might be different this time round ...

With the programmed end of the EPP/S&D duopoly, the process will probably be even harder to implement in 2019. The candidate who is appointed during the European political party congresses will have to be accepted by the other parties that will make up the majority. Moreover, E. Macron and A. Merkel have already expressed their doubts about the legitimacy of this procedure. Indeed, according to the terms of the treaties, it is the European Council of Heads of State and government who appoint the executives of the common institutions, even if they have to be approved by the European Parliament.

Moreover is the parliamentary principle, whereby the head of the party that wins obligatorily becomes Prime Minister, for example as in the UK, well applied to the European institutions, whilst some parties that have come out ahead in the recent national elections have not been appointed automatically to lead the government of their country (cf. Luxembourg in 2013 and Portugal in 2015)?

Finally, bringing Europe closer to its citizens is an imperative that is difficult to reconcile with appointments made via political parties, and therefore by a small number of active members, of its highest-ranking leaders.

In a trio no one doubts that discussions after the election will go well.

Until now the traditional distribution of roles has been made according to political labels and geographical balances. In 2014 the EPP won the Presidency of the European Commission (Luxembourg) and that of the European Council (Poland), the S&D got the first part of the Presidency of the European Parliament (Germany), the post of first Vice-President of the Commission (The Netherlands) and that of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (Italy). The latter post was finally given to a woman.

Undoubtedly, we shall now have to add other criteria to this, for example, making more room for women. Why not as the head of the European Commission, even if the candidates are nearly all masculine? It is not certain that the post-election consultations between the various parties will lead to the appointment of officially declared candidates and they would be well advised to take the imperative of parity more seriously - since this is now indivisible from true representativeness, i.e. legitimacy.

Likewise, it will no longer be possible to divide the Presidency of the European Parliament into two and it might be a problem to divide it into three! It would be a welcome novelty for the institution's stability to attribute the whole legislature of five years to a person designated according to his or her moral authority or experience. Again, it would be symbolic to appoint a woman. We might recall that only two women have occupied this position in the last 40 years. Simone Veil from 1979 to 1982 and Nicole Fontaine from 1999 to 2002. How much time will we have to wait for this to happen again?

Finally, by chance the calendar would have it that the 8-year mandate of the President of the European Central Bank will be up in 2019. Hence there will be six important positions in the European executive that will have to be filled. And rest assured, that Heads of State and government will - as often is the case - have the last word.

It is probably one of the hopes of the French President, who is counting on the new situation created by this atypical and unusual state of affairs. Given the rise of extremes, populists and nationalists, he hopes to federate the parties on the centre-right and centre-left which have pronounced clear European views.

His arrival in office in France upset the traditional political forces and some fear that he will do the same in the European arena. Many observers admit that the Union can no longer continue to function as it has done in the past. He might want to be one of those who help towards settling this complicated equation of the European consensus, by supporting the constitution of a stable political and institutional majority for the five years to come.

As for the electorate it is hoped that they are aware of what is at stake in the election which, this time, is different and that given the external and internal challenges being made to the European Union many will turn out to ballot.

[1] For France we should add another change in 2019. MEPs will no longer be elected as part of the major inter-regional constituencies (8) as had been the case since 2004, but as part of a national framework, as prior to that date.

[2] During the legislature of 1999-2004 the coalition was made between the EPP and the Liberals (ELDR at the time). Nicole Fontaine (FR, EPP) was the President from July 1999 to January 2002 then Pat Cox (IE, ELDR) until June 2004.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :