Freedom, security and justice

Yves Bertoncini

-

Available versions :

EN

Yves Bertoncini

Consultant in European Affairs, Lecturer at the Corps des Mines and ESCP Business School

At this stage, this double "co-owners' crisis" has given rise to a race between the return of temporary national border controls and the strengthening of European cooperation, notably marked by the Europeanisation of the external borders' control[1]. It is worthwhile to view these developments in perspective, whilst negotiations over the Union's "asylum policy" should be finalised mid-2018 and the terrorist threat remains high.

The favourable outcome of this "co-owners' crisis will depend on the adoption of new political and operational guidelines over the next few months and also on the ability of the national and community authorities to support the remarkable flexibility of the Schengen Code, with communication that is better adapted to the "spirit of Schengen"[2].

1. "The Schengen Area" and the "refugee crisis": a lack of solidarity and trust now abating?

During the refugee crisis, the lack of solidarity between the Member States of the EU notably emerged in the difficulty the latter had in distributing asylum seekers who had arrived in Greece and Italy in a balanced manner. However, the lack of confidence between States, and even their mutual mistrust, have been the main sources of tension affecting the Schengen area and which have not all yet been dispelled.

1.1. A widely commented lack of solidarity

It was in support of the countries on the front line of the refugee crisis that in September 2015 the Commission proposed to the Council the adoption of a relocation mechanism of the great number of asylum seekers who were arriving in Greece, Italy and Hungary. Back then this meant the urgent provision of a "hotfix" to the idea behind the Dublin Regulation, which provided that all asylum requests should be made and processed in the country of first arrival, which de facto placed the countries of the South of Europe in an imbalanced situation in view of the others. This emblematic "hotfix" aimed to complete some of the more hidden European solidarity mechanisms (participation in the financing of the external borders or financing the reception of asylum seekers in particular).

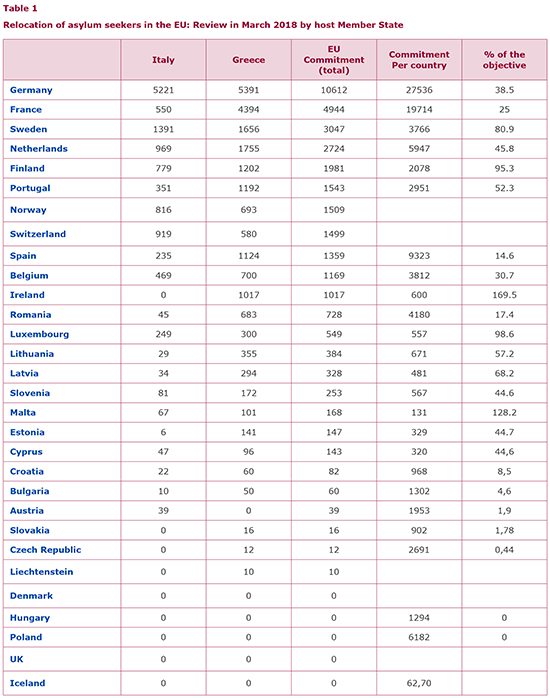

Source: Relocation of asylum seekers-Table ©EuropeanMigrationLaw.eu

Source: Relocation of asylum seekers-Table ©EuropeanMigrationLaw.eu

The relocation mechanism adopted by the EU council aimed to organise the transfer of 160,000 asylum seekers from the countries on the front line towards the other Member States within two years, i.e. by the autumn of 2017. Since Hungary refused to accept this European solidarity[3], this meant first relocating around 100,000 asylum seekers from Greece and Italy and 60,000 more once this first goal had been achieved.

The European Commission indicated that at the end of March 2018 only 34, 323 of these asylum seekers (see table 1) had effectively been relocated from Greece (21,994) and Italy (12,329), i.e. 35% of the first objective (and 21.5% of the overall objective of 160,000)[4]. Except for Ireland and Malta, whose commitments were limited, none of the EU Member States have wanted or been able to fully implement the relocation decision taken in the autumn of 2015. As an example, France has taken in fewer than 5000 "relocated" asylum seekers, 4,400 of whom are from Greece and only 550 from Italy. It is therefore very far from the goal of the "30,000 and not one more", declared by Manuel Valls in September 2015[5].

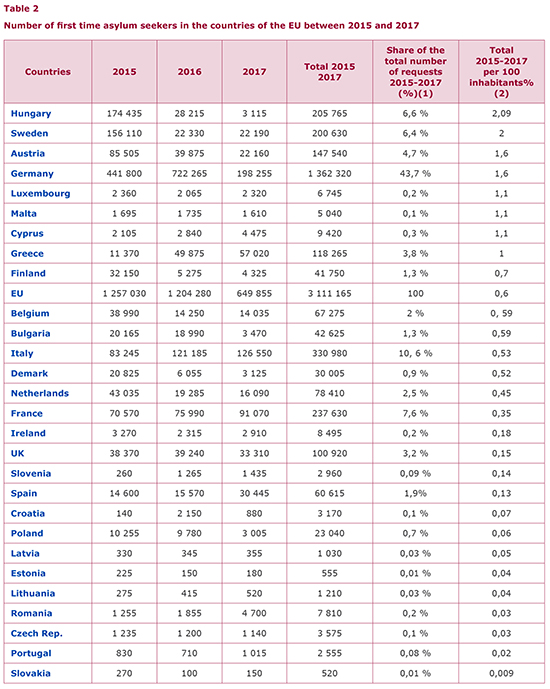

Of course, we have to look at all of the asylum requests addressed in the EU Member States, beyond the relocations alone, to assess the extent to which they have been involved in the recent refugee crisis (see table 2).

This assessment first reveals that the number of asylum requests in the EU over the period 2015-2017 lay at just over 3.1 million (3,111,165), around 0.6% of the European population (or 6,000 per million inhabitants).

It also highlights the fact that after the peak in 2015 and 2016 (1.2 million requests per year), the number of asylum requests registered in the Member States halved in 2017 (total 650,000). This figure therefore dropped to a level that was comparable with the years preceding the crisis (562,000 requests in 2014).

This assessment also leads to the conclusion that Germany registered the greatest number of asylum seekers in the period 2015-2017 (more than 43% of the requests), far ahead of Italy (10%), France (7.6%), Hungary (6.6%) and Sweden (6.4%). However it's when the share of asylum seekers is contrasted with the number of inhabitants of the host country that we can see the degree of "exposure" of the Member States to the recent migratory flows: Hungary and Sweden find themselves at the top of the list, at 2% of their population, ahead of Austria and Germany (1.6% each), then Luxembourg, Malta, Cyprus, Greece and Finland. The other countries lie below the European average of 0.6%, notably France (15th out of 28, at 0.35%) and most of the countries of Central Europe and the Baltic.

In this context the request for solidarity between Member States in terms of asylum is likely to continue over the next few quarters: on the one hand, in view of the respect of the commitments made in terms of relocation and a possible renewal of this mechanism beyond the initial deadline of autumn 2017; on the other hand as part of the ongoing revision of the "Dublin Regulation", which will notably focus on a possible non-implementation of the principle of assessing asylum requests by the country of first entry in the event of mass influx.

Source: Eurostat Data, Calculations Yves Bertoncini

Source: Eurostat Data, Calculations Yves Bertoncini

(1) The percentages have been rounded down to the lower decimal (2) Based on the population of the Member States on January 1st 2017.

NB: These figures correspond to people who have made a first asylum request in the year in question. They are distinct from the number of requests pending a response which totalled 926,990 at the end of December 2017 for the EU around 443,000 of whom were in Germany, 152,000 in Italy, 57,000 in Austria, 51,000 in Sweden, 47,000 in Greece, 38,000 in Spain and France (i.e. 4% of the total) and 665 Hungary[6]. These figures are also distinct from the number of requests accepted by the EU member states: in 2017, this proportion varied from 12% (Czech Republic) to 89% (Ireland) in their first instance decisions (the EU average was 46%)[7].

1.2. A two-fold lack of confidence now abating?

It is a lack of confidence between States that has caused the main tension affecting the Schengen Area.

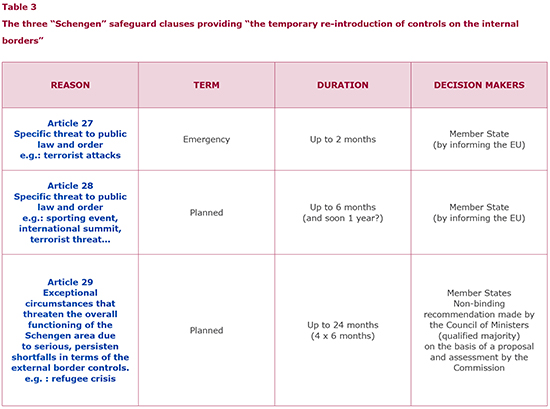

This was because they suspected that Greece and Italy did not have either the ability, or even the will to assume the effective control of the external borders that many other Member States deemed that they were "guilty parties" on whom to lay the blame, as much as they were "victims" to help. This mistrust was inevitable vis-à-vis the countries whose administrative capacities do not enjoy a strong reputation with their partners. It was made worse by the fact that these two countries are especially and above all transit countries for the asylum seekers and migrants, in whom they had no real interest in registering or keeping within their borders. This mistrust was expressed during 2015 and 2016 to the point that national border controls were re-introduced in 9 of the 26 countries in the Schengen Area[8], a re-introduction provided for by the Schengen Code (see table 3), but often activated in line with a non-cooperative rationale between the States in question.

Source : Schengen Border Code Data/Eurlex, Regulation 562/2006 revised by Regulation1051/2013. Yves Bertoncini

Source : Schengen Border Code Data/Eurlex, Regulation 562/2006 revised by Regulation1051/2013. Yves Bertoncini

The temporary return of national border controls has however been accompanied by a parallel movement in the Europeanisation of the external borders'control of the Schengen Area.

The creation of "hotspots" in Greece and Italy first aimed to respond simultaneously to the lack of solidarity and confidence between the Member States. In the guise of helping Greece and Italy financially and from a human point of view, it led to the dispatch of national and European experts, whose goal was to help the national authorities to effectively meet their obligations in terms of border control and the registration of asylum seekers. This was precisely why this project caused the reticence of the potentially "beneficiary" States, especially if at the same time this action did not go together with the effective relocation of asylum seekers.

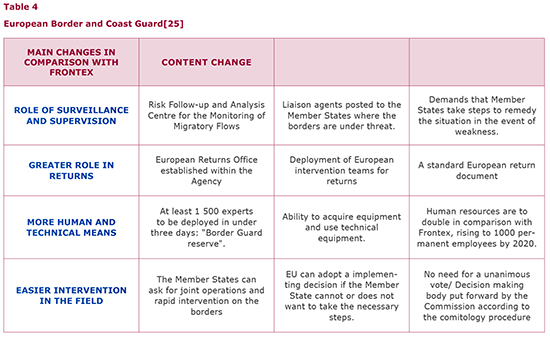

The establishment of a "European Border Guard Corps" (see table 4) extended this trend in reducing the lack of confidence between Member States and was a welcome "federal leap", made possible by the seriousness of the migratory crisis. It has meant that the race between re-introducing national border controls and the Europeanisation of the external control of the Schengen Area borders could now be won to the benefit of European integration.

Another type of trust deficit has damaged smooth cooperation between the Members of the Schengen Area, finding its origins in Germany.

Angela Merkel's decision to announce that she no longer intended to implement fully the Dublin Regulation and that Germany could take in asylum seekers from Syria was criticised for two reasons, mezza voce in countries like France and more loudly by the countries of Central Europe. It was criticised regarding the method, deemed unilateral, but also for the consequences that this decision would have for many other countries facing a massive, uncontrolled influx of asylum seekers at the end of 2015 and during 2016, particularly Austria and Hungary. The EU-Turkey Declaration negotiated under the guidance of Angela Merkel in March 2016 then led to the 20-fold division in the flow of asylum seekers using the Balkan Route[9]. But the political damage created by the German Chancellor's initial decision amongst in the neighbouring countries has probably remained unrepaired.

The lack of trust between Member States is still deep as regards the asylum seekers who are already on European soil, but who might leave their host country to make a request in another country. It was the mistrust regarding these so-called "secondary" waves that conditioned the upkeep of temporary national border controls in five Member States[10]. This tacit mistrust seems to have encouraged the French government's firm attitude, as it intends to bring in a new "asylum-migration" bill, the implicit aim of which might be to send a negative message to asylum seekers. This mistrust on the part of the French authorities is a paradox for at least three reasons:

• France is not on the front line of the "refugee crisis" (see table 2): it lies 15th in the ranking out of 28 in terms of asylum seekers requests per inhabitant[11] ;

• It elected a president who boasted the "spirit of conquest", i.e., who carried a vision of the positive sides of France and which seemed compatible with the reception of a greater number of asylum seekers;

• The French authorities would have an interest in proving greater solidarity with countries like Italy and Germany, which are more exposed to flows of asylum seekers, if they want to convince them to engage on their side in terms of the implementation of an ambitious European agenda.

1.3. Acting at the source to bring Schengen out of the migratory crisis

Bringing "Schengen" out of the migratory crisis supposes going further to increase the trend to europeanise the management of the flows of asylum seekers on the basis of three complementary chapters.

The strengthening of the "external dimension of the Schengen area" i.e. acting at the source of the refugee flows, is the focus of quite a wide consensus between the Member States. Stated at the summit in Malta in November 2015, the goal is to conclude cooperation agreements with the African and Mediterranean transit countries. As in the agreement concluded between the EU and Turkey this means supporting transit countries financially so that they can help the millions of asylum seekers they host, and also to encourage them to control the flow of seekers more, and also to accept the return of rejected asylum seekers[12]. Influenced by Realpolitik, this strategy has already led to a massive reduction in the flows of seekers using the Balkan route via Turkey. It is more difficult to implement this in Sub-Saharan Africa and even more so in Libya given the failure of the State in this country.

The strengthening of the Schengen area also aims to find a base in the sustainability of the European Border Guard Corps, outside of crisis periods. Indeed it would be logical for the control of the external borders to be shared by all of the Member States, including its financing in the main by the European budget: they are our borders in effect, since the people who cross them are said to then have the right to move freely within the Schengen area for a maximum period of three months. Undoubtedly this is what it will cost to drastically attenuate the lack of trust between the Member States for the temporary re-establishment of the internal borders to largely become unnecessary.

The long-term Europeanisation of border controls seems inseparable from a strengthening of the solidarity mechanisms linking the 26 countries of the Schengen area, on a political basis that is both legitimate and effective.

This firstly supposes that the Dublin Regulation will be reformed to distinguish more clearly what is deemed as a normal situation (in which asylum requests are processed by the country of first entry) and crisis situations, in which solidarity mechanisms have to be introduced.

These solidarity mechanisms should also be defined on more pragmatic bases and via more consensual decision-making procedures. Indeed, of what use is it to impose coercively relocations that some States do not want[13], but which did not work any better in the voluntary countries, notably because the asylum seekers in question do not want to be hosted there? Undoubtedly, it would be preferable, whilst firmly maintaining a European solidarity principle, to allow Member States to fulfil their duty in various ways: it might for example mean hosting relocated asylum seekers, but also contributing financially to their reception in other Member States[14].

Finally, it would be good if the "resettlement" mechanism for asylum seekers were to be privileged: it provides for the assessment of their request outside of the Schengen area borders, then the direct transfer of asylum seekers who have been recognised as "refugees" to the country that has accepted to take them and where they want to go. This mechanism therefore has the merit of avoiding the phenomenon of journeys which take asylum seekers to the Union's external borders, then from one country to another, under the control of smugglers, who unashamedly exploit their distress. It has been used to a limited degree to date but has already led to the resettlement of more than 18,000 asylum seekers, often from Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey (more than 3 000 in Norway, more than 2 000 in France and the UK, etc.)[15]. It would be welcome to continue along this path over the next few years, since it could also encourage more consensus amongst the Member States.

2. The "Schengen Code" and terrorism: instinctive solidarity, strength-providing cooperation?

The terrorist attacks that occurred in Europe led to much more instinctive solidarity between countries, several of which have been tragically struck over the last few years, whether they were members of the Schengen area or not. Police cooperation between these countries has proven much more problematic and this now means strengthening this as part of the "Schengen Code".

2.1 European solidarity favouring the adoption of many anti-terrorist measures at European level

The terrorist challenge and threat has led Europeans to adopt many additional measures over the last few years.

The Paris attacks of 13th November 2015 facilitated the final adoption of the "Passenger Name Record" (PNR) thereby organising the consultation of air passenger files as well as the adoption of several security measures: tightening of the regulations regarding the arms trade, strengthening of the fight to counter the financing of terrorism, the modification of the "Schengen Code" so that Europeans can be systematically controlled on their return to the Schengen area etc. [16].

The November 2015 attacks also gave rise to the first triggering of the solidarity clause provided by article 42.7 of the TEU, leading to countries like Germany contributing to military intervention in Syria, to fighting terrorism at the source and not on the borders. This collective response by the Europeans has not been recognised or valued as it justly deserves: it is up to the national and European authorities to highlight this more.

2.2. A deficit in confidence between Member States that still needs to be repaired

Although the period 2015-2016 was a turning point in the mobilisation against terrorism at European level, this will only become fully effective if the States have enough trust in each other, which seems to be far from being the case. The announcement of the reintroduction of systematic controls on the Franco-Belgian border at the end of 2015 went hand in hand with reciprocal critics made by the police and judicial bodies against each other in both countries; their cooperation is however decisive in terms of an efficient fight to counter terrorist networks[17].

The terrorists are not arrested on the borders, but where they are hiding and therefore via determined, concerted action by the Member States' police and intelligence services. How though can we succeed in making these exchanges in information, which are already difficult between national services, fluid and fruitful at European level, if they have to be organised between the Member States who sometimes still spy on each other[18]?

The security and political challenge for the Europeans is to encourage convergence in terms of counter-espionage and the fight to counter terrorism, on the basis that it is about fighting criminals and that it is possible and desirable to share more information. A change in paradigm must occur in view of the counter-espionage practices inherited from the Cold War if we are to move on from the era of small scale improvisation to the industrial era of intelligence exchange. Indeed, it will be against the effective progress achieved in these exchanges of intelligence that a major part of the fate of the Schengen area will be gauged, which will again be put to the test and will even be accused with every new terrorist attack.

In this context increasing the Schengen area's resilience supposes the combination of two complementary approaches:

- one that aims to adjust the Schengen Code so that it can better organise the triggering of safeguard clauses in the face of terrorist attacks in the long term: this might mean increasing the authorised timespans (up to three years) on condition that the country in question coordinates matters with its neighbours and that it obtains their agreement;

- the other that aims to strengthen European military cooperation to strike at the sources of terrorism in the Middle East and the Sahel, but also in terms of intelligence exchange: undoubtedly France and Germany are well placed to launch initiatives in this area, since it seems difficult to extend these already to all Member States.

3. "Schengen" and mysticism in politics: escaping the trap

In opposition to the predictions announcing the "end of Schengen", we can state that no country in the Schengen area has wanted to leave it or be excluded from it. We might also stress that the rules of the Schengen Code were respected during the refugee crisis, then in the face of the terrorist threat, even though they were interpreted in an extremely flexible manner.

Resistance on the part of the Schengen area will however only be lasting if its proponents manage to extricate it from the crossfire of national governments that are over valuing the protective dimension of borders and "Europhile" governments that minimise the security aspects of the founding agreement.

3.1. Rising beyond the mystic of the national borders: defending oneself without remaining on one's own goal line

It is striking to note that many national authorities most often privilege political communication valuing the protective aspect of the national borders: they even announce quite martially the "closure of the borders", which is materially impossible, except if walls are built as during the Cold War.

This political communication is issued on an emotional register which can sometimes take precedence in the event of major attacks[19]. It also reflects the mythological protective dimension of the "good old national borders" - including in a country like France, which has already measured the limits and the vanity of the Maginot Line[20]... This type of response is, for example, much more seldom in Germany where the authorities have rarely gone as far as talking of the lack of control on the borders as a major problem in the event of terrorist attacks.

In the face of terrorism, the supposed aim of this political communication is to reassure the population, whilst a very tiny number of terrorists have been arrested during border controls. It is when they are not on their guard that we have to target terrorists, which also supposes more European and international cooperation in terms of police, judicial and even military work. Referring to the protective nature of the national borders is both paradoxical and counterproductive, since most terrorists are born within the country where they strike: some governments indeed tend to maintain the equation "terrorism=foreigner=threat", which is not really favourable in terms of creating a culture of cooperation between European States.

In terms of migration the aim of communication focused on the national borders sends out a negative message to migrants but also to the smugglers. The objective is to divert them from the country in question, even if effective controls on the national borders are not really re-introduced. But this very quickly reaches its limits when the smugglers check whether controls are effective or not, on which parts of the border, in order to adjust their route.

Given the terrorist threat and also the migratory challenge, political communication focused on the national borders delegitimises the Schengen area in part. It makes "Schengen" seem like an "area" that does away with controls and not as a "Code" which re-organises them to make them more efficient. "Schengen" is therefore considered a "Pandora's Box" rather than a toolbox[21], and then not as one of the instruments that will lead to a strengthening in the protection of the populations of Europe[22].

3.2. Tempering the pro-European mystic of circulation: Schengen is an area and also a Code

"Schengen" is defended little or poorly in the face of these national responses because many of its most fervent supporters indulge in a "mystic of circulation" that tends to cancel out the dimension of security.

Above all Schengen is assimilated to the additional freedom linked to the suppression of systematic controls on the national borders, the temporary re-introduction of which is often incorrectly presented as a "suspension" of the founding agreement or a betrayal of the "Schengen spirit"[23].

Everything occurs as if the Schengen agreement, first signed by five countries as part of an intergovernmental framework, had not been completely assimilated by the European institutions, despite the progressive integration of its judicial and police measures and tools into EU common law. It is as if the culture of "circulation", resulting from the Rome Treaty and its "four freedoms" were still "ultra-dominant" in Brussels, to the point that the necessary consideration of the challenge to security has been downplayed.

In the present context it would therefore be all the more welcome to stress that the introduction of the Schengen area went together with a determination to strengthen police and judicial cooperation between States, by reconciling freedom and security within a European framework in the best way possible. This is why it includes safeguard clauses whose triggering means "implementing Schengen": these clauses are an integral part of the Schengen Code and must be accepted and promoted as such. Whilst the conclusions of the Bratislava summit talked of the need to "return to Schengen", they of course refer to the non-cooperative approach that led some Member States to step up the triggering of the safeguard clauses[24]. But they also constantly repeat the political mistake which will damage the resilience of the Schengen area in public opinion.

To foster this resilience, it would also be good to strengthen communication regarding the security dimension of the Schengen area through some emblematic actions. And so, it would be welcome for the Europeanisation of the controls on the external borders to be illustrated more concretely with images of national staff working as part of the European Borders Guard Corps (see table 4). For the time being these images are but rare, even inexistent, whilst the media is saturated with images of cohorts of asylum seekers and migrants trying to enter the Schengen area. Likewise, it would be good for the heads of State and government to plan a meeting under the Schengen format, in the same way as they started to meet under the euro zone format to rise to the financial crisis. These high level political summits, supported if necessary by trips to the borders of Schengen, would show more clearly Europe's determination to act together in the face of joint challenges, which are a priority in the eyes of public opinion.

Source: Y. Bertoncini & A. Vitorino, European Commission data.

Source: Y. Bertoncini & A. Vitorino, European Commission data.

3.3. European interdependency, Schengen's ultimate firewall

Their intrinsic defects aside, the dominant national and Europhile governments in the Schengen area all understate the economic interdependency that justified its creation. Whilst it was established to simplify the life of lorry drivers, border workers and their companies, on whom its disappearance would inflict severe punishment, "Schengen" is often seen as an accomplishment that benefits the elites (business men, the Erasmus generation etc.) thereby cutting it off all the more from the "masses" that it is supposed to protect.

Hence this also means that a two-fold adjustment of political communication surrounding the Schengen area would be welcome:

• To recall that its creation owes much to economic and pragmatic considerations and not to some kind of "Europhile" internationalist ideology.

• To stress that the dismantling of the Schengen area would lead to significant economic, financial and human costs, for which many Europeans would have to pay.

Listed by many experts[26], the costs of dismantling the Schengen area would be associated with queues on the borders for road hauliers, and those living on the borders, as well as import and export businesses; with rising prices of ordinary consumer goods (fruit and vegetables) for Europeans; with the budgetary and tax impact of the re-introduction of border control measures (material, technological, human resources etc.); etc.

The national authorities are particularly well placed to issue this double message since more often than not they quickly relinquish the re-introduction of systematic internal border controls enabled by the Schengen Code: indeed, they know that the extension of systematic border controls would have extremely negative economic and social consequences, without making any significant gain in terms of security. It is up to them to take stock of the dangerous game that they play as they announce the "closure of the borders" which is but virtual, but which lends credit however to the false idea that "closing the borders" would not have any negative impact.

***

The race between national and European border controls in the Schengen area is not yet over. It is likely that it will end in the prevalence of a European rationale, simply because of the disproportionate human and economic costs caused by a return to the past that would provide no real added value from the point of view of security. However, this prevalence would be encouraged by the promotion of national and European communication that is better adapted to the spirit of Schengen, as well as by the adoption of more effective guidelines in dealing with migratory and terrorist challenges.

The present race would be a fools' game if it simply masked what is vital for the Europeans, which means acting well beyond the borders, to address the conflicts that cause the influx of migrants at their source on the one hand, and terrorist hotbeds on the other. This supposes even more cooperation and solidarity between the Member States who would still be the primary victims of their lack of efficiency on the diplomatic and military fronts, whatever the fate reserved for "Schengen".

[1] Regarding the political nature of the " Schengen Area " crisis, see the hearing with the Investigative Committee at the French Senate: http://videos.senat.fr/video.286740_586b69312cd4b.audition-de-mm-yves-bertoncini-et-jean-dominique-giuliani

[2] I warmly thank Yves Pascouau for his comments during the drafting of this policy-paper.

[3] Hungary and Slovakia challenged the legality of the decision taken by the Council in terms of relocation of asylum seekers but they were rejected by the EU's Court of Justice.

[4]see www.europeanmigrationlaw.eu http://www.europeanmigrationlaw.eu/fr/articles/donnees/relocalisation-des-demandeurs-dasile-depuis-la-grece-et-litalie

[5] The figure of 30,000 quoted by Manuel Valls referred to France's total " quota " based on the target of 160,000 asylum seekers to relocate.

[6] National and European data regarding asylum requests are available on Eurostat's website

[7] For more information on asylum acceptance rate in the EU member states: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/8817685/3-19042018-AP-FR.pdf/89ae56ea-112c-456b-ba05-7944733f6de1

[8] 8 countries recently triggered the safeguard clauses provided by the Schengen Code, referring to the refugee crisis: Germany, Austria, Denmark, Malta, Norway, Hungary, Slovenia and Sweden. France referred to the terrorist threat.

[9] Although the number of migrants rose over 15,000 per week before March 2016, the number of migrants crossing the Greek-Turkey border lay for example at fewer than 700 per week in the summer of 2017. On this issue see the 7th Commission Report on the implementation of the EU-Turkey Declaration

[10] In March 2018, 6 of the 26 Schengen area countries were maintaining their safeguard clauses: Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, for reasons linked to the refugee crisis, together with France, which still officially refers to the terrorist threat.

[11] The recurrent tension in Calais are symbolic of the fact that France is in part a transit country (asylum seekers and refugees in Calais want to get to the UK).

[12] The average rate of return of rejected asylum seeker lies between 40 and 50% over the recent period.

[13] The European Commission has just launched infringement proceedings against Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic for the non-implementation of the relocation decision regarding asylum seekers dated September 2015.

[14] It is for example with this in mind that the construction of social housing in France is organised, based on a goal of 25% per community: i.e. communities achieve this goal or they contribute financially to the actions undertaken by others.

[15] For a review of the European relocation mechanism introduced in 2015, see https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20171114_resettlement_ensuring_safe_and_legal_access_to_protection_for_refugees_en.pdf

[16] Notably requested by France, a further modification of the Schengen Code might be undertaken in 2018 for a clearer management of Member States' response in the event of terrorist threats.

[17] The usefulness of European cooperation was then confirmed by the arrest of Salah Abdeslam, then by his rapid delivery to the judicial authorities under a European Arrest Warrant. Salah Abdeslam was controlled on the night of 13th and 14th November 2015 on the Franco-Belgian border, but for nothing given the lack of information exchange between the two countries.

[18] As recalled by the espionage of the French Foreign Office by German secret services.

[19] Hence François Hollande announced the "closure of the borders" in the night of 13th to 14th November 2015 whilst France had announced that it intended to re-introduce temporary border controls in the morning of 13th November in view of the organisation of the "COP21".

[20] Even when attacks occurred in 2017 in the UK, outside of the Schengen area, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe declared that he had asked for a tightening of controls on the French borders.

[21] Amongst the tools provided by the Schengen Code: the "Schengen Information System", mobile customs and excise, control of the border area, right to observation and pursuit beyond the national borders etc.

[22] See for example "Schengen is dead ? Long live Schengen!", Jacques Delors, Antonio Vitorino, Yves Bertoncini and the participants of the European Steering Committee 2015 of the Jacques Delors Institute, 2015

[23] See for example "Back to Schengen-a Roadmap", European Commission COM 2016 (120) Final, March 2016

[24] These Member States also referred to different legal bases (articles 27, 28 and 29) to formally respect the deadlines set by the Schengen Code.

[25] The creation of the European Border and Coast Guard was achieved based on a transformation/extension of the "Frontex" agency.

[26] See for example "Les conséquences de la fin de Schengen", Yves Pascouau, Euradionantes, 2015; "The costs of non-Schengen", European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament, 2016; Anna auf dem Brinke, "The economic costs of non-Schengen: what the numbers tell us", Jacques Delors Institut - Berlin, 2016 and Vincent Aussiloux, Boris Le Hir, Les conséquences économiques d'un abandon des accords de Schengen, France Stratégie, 2016

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :