Economic and Monetary Union

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

Part I

The European Union and the UK

The "budgetary conundrum" of the Brexit bill

After a reminder of the issues at stake, the budgetary impact of the Brexit must be analysed in sequence. Until March 2019 and post-March 2019, and until the end of the implementation of the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF).

1. The context of the budgetary negotiation

1.1 Budgetary Data

1.1.1 A key partner in the European budgetary system

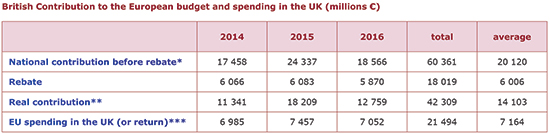

With the Brexit the European Union will be losing a contributor to the European budget. Whether this involves the country's gross contribution to the budget (Its financial participation), or its net contribution, i.e. after deduction of European budgetary spending in the UK[1].

Source: Commission, Financial report, layout - author

Source: Commission, Financial report, layout - author

* Contributions based on VAT and the GNI are the UK's own resources but since they are levied on the budget of the Member States they are normally considered as national contributions.

** The real contribution is mainly calculated via the difference between the gross contribution less the rebate - but this result is also subject to some corrections and adjustments.

*** 52 % of European spending in the UK are of an agricultural nature

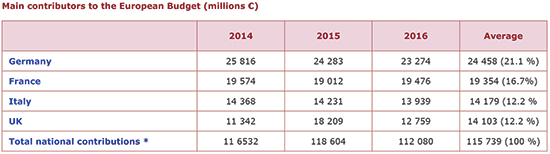

Source: Commission, financial reports - layout - author

Source: Commission, financial reports - layout - author

*NB National contributions represent 82 % of the EU's resources. To this we have to add the traditional own resources, the transfers and various products such as fines and external contributions....

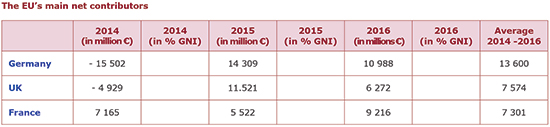

In spite of the rebate the UK is still a major net contributor to the European budget[2]. It is the second biggest net contributor, far behind Germany and just ahead of France. The net contribution totals 38.7 billion € over 5 years (2012/2016). The recent average has been 7.5 billion €. Normally this represents the loss of potential revenues caused by Brexit.

Source: Commission, Financial Report 2016

Source: Commission, Financial Report 2016

1.1.2 An unusual partner: the British rebate

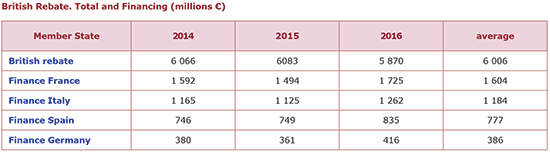

The budgetary particularity of the UK mainly emerges via the British rebate. The principle, approved by the European Council of Fontainebleau in 1984 is simple: "It has been decided that any Member State that has to bear an excessive budgetary burden in comparison to its relative prosperity is eligible, in due course; to enjoy an adjustment." In 1984, the State in question was obviously the UK. The country was one of the least prosperous in the European Economic Community and given the structure of the budget at the time, crushed by the weight of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), it received very little European funding. The country deplored the fact that its net contribution was greater than all of the other Member States and demanded a "fair return". The rebate helped reduce the net balance (negative) vis-à-vis Europe. The adjustment emerged in the shape of a reimbursement of the payments made by the British to the European budget to a total of 2/3 of the country's net contribution. One year's compensation is paid in year n+1. This "cheque", another name for the rebate, is financed by the other Member States. After this, several countries also received a rebate on the rebate, it was France that ensured the major share in financing the rebate, i.e. 26% in all[3].

Source: Commission, annual financial reports

Source: Commission, annual financial reports

Although the principle is simple, the calculation methods are extremely complicated[4] and established by a decision on own resources, adopted by the Council[5]. It is ironic to note that the British, who liberally criticise European bureaucracy, were the cause, "of the quintessence of European budgetary complexity"[6]. A complexity which has increased as enlargement has followed enlargement, adjustment after adjustment, rebate after rebate.

The rebate has always been the focus of founded yet vain criticism. The principle of the rebate is contrary to the rules of solidarity, which forms the foundation of European integration, and the UK is the only Union country whose share in the funding of the budget does not correspond by far to its economic weight[7]. This criticism is part of a ritual in budgetary debate. But the rebate has become a particular feature of the British identity. Since budgetary financing rules are adopted unanimously, it is illusory to think that the rebate will disappear. Only the Brexit will bring the British rebate to an end.

1.1.3 Customs Duties

This budgetary issue seems to have been forgotten by observers. However it represents 3 billion €.

Customs duties, which form almost all of the "traditional own resources" are only partially taken into account in the calculation of the net balances. The Commission deems that customs duties cannot be assimilated to national contributions, levied on national tax products, whilst these are genuine community resources, which result from the application of the common external tariff on extra-EU imports[8]. Moreover, the importer who bears the customs duties is not always established in the country that receives them. Customs duties are increased in the main points of entry (Rotterdam Effect). However, it must be said that if traditional own resources are "genuine own resources", the exit of the UK will certainly lead to a clear loss in customs revenues.

The budgetary issue is highly significant. The country is the second collector of customs duties in the Union, behind Germany. British imports (extra-EU) are subject to customs duties to a total of 3.7 billion € and are the source of 3 billion € of the European budget's revenues, after the guarantee deduction of 20% on the revenue collected. This revenue will disappear with the Brexit in March 2019. Customs duties paid on British imports (extra-EU will then be totally integrated into the national revenue. [9]. The budgetary question in the Brexit is therefore involving a total revenue loss of around 10 billion €.

1.2 Procedures

Article 50 TFEU defines the withdrawal procedure[10]. This was triggered by the notification made to the President of the European Council on 29th March 2017[11]. If no agreement is met within the next two years, i.e. on 29th March 2019, the treaties will cease to apply to the UK, except if an additional time period is agreed unanimously by the European Council. The latter defines the guidelines of the negotiations and concludes the withdrawal agreement after a qualified majority vote and the approval of the European Parliament. In April 2017, the European Council decided on a negotiation arrangement and identified the issues that will be the focus of the withdrawal agreement. It also created a Brexit task force before the triggering of the procedure provided for in article 50, under the management of Belgian Didier Seeuws.

The agreement is negotiated in line with article 218 § 3 TFEU. The Commission presents recommendations to the Council which adopts a decision allowing the launch of negotiations. On 27th July 2016 the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, appointed Frenchman Michel Barnier, as the negotiator in chief, responsible for the Commission's working group and for the preparation of and for undertaking the negotiations with the UK in virtue of article 50 TEU. The working group has been operational since 1st October 2016. It is organised according to three main themes (internal market, budget and trade). The budgetary issues have to be settled via a financial regulation. Michel Barnier is working closely with the other States. The national authorities are obviously deeply involved. The time for political compromises will come later. He ensures that he has the unanimous support of the other States. He convenes the "Sherpas" of the national authorities regularly and has toured the capitals of the Member States twice since he took office.

The timeframe is very short. Negotiations are taking place in sessions and have to be concluded by October 2018, to provide enough time for approval by Parliament and to free the European elections of the issue. Negotiations are progressing more or less slowly (access to the single market, trade relations and citizens' rights) but it is clear that the budgetary issue is one of the most conflictual. The European Commissioner for the Budget admitted that "negotiations over the budget will be very difficult."[12] This is not surprising. Michel Barnier regularly deplores these difficulties.[13] On 20th October 2017 the President of the European Council drew up a first interim report recalling that "the information whereby there is a cul-de-sac between the EU and the UK has been exaggerated. Although progress has not been adequate, this does not mean however that there has been none at all. "[14]

1.3 The parties' positioning

1.3.1 Reference points regarding the British position

Should the financial settlement be separate as desired by the 27 other Member States or should it be part of a whole as the British wish? No budgetary agreement without an agreement over the future relations with the Union for example. Final agreement or transition period? The UK does not want to commit to a financial agreement as long as the EU does not want to discuss a transition period.

As much as its exit of the Union has upset the country's cohesion, it has found itself rather more united over the negotiation of the budgetary chapter. The argument about what the Union is to cost the UK is easy to understand and has always been well understood. The British, in spite of the rebate, are still the second biggest net contributors. Even though British Prime Minister Theresa May lost her absolute majority after the June 2017 elections, she is still able to defend British interests, "to protect Britain in Brexit" which is sometimes presented as the negotiation of the century. The "catastrophic dinner"[15] of 26th April 2017 between JC Juncker and T May highlighted the gulf between their respective positions. Starting point for the British is zero. "Not a penny for the EU". However, some observers prefer to temper This position of power saying that it is just a negotiation façade. The country especially fears that the 27 will stand on a punitive stance, that the Union will make them pay both in the real and the figurative sens for this departure and that the bill will be sufficiently high to dissuade other State from following the same path.

1.3.2 Reference Points regarding the Union's position

Britain's singularity has often irritated the 27 Member States. Via the rebate the country is the only one which makes the others pay part of its contribution. A share of opinion in several countries sees the British departure without any excess of displeasure. Without displeasure and without concession.

The position of the 27 is clear and simple. "27 of us will not accept to pay for what was decided by 28. Nothing more nothing less," insisted the negotiator. And unanimity on this is strong.[16] Contributors do not want to take on the UK's share and the beneficiaries do not want to lose what they had as 28. A position which has been defended by Germany and France on several occasions. Brexit offers an opportunity to take a stance against everyone else - particularly against the French.

1.3.3 An French-English budgetary war?

The budgetary negotiation in the Brexit brings an age old French-English rivalry back into the open. France is irritating. France has not concealed its goal to take advantage of the Brexit. The regions are positioning themselves in this sense, France is prepared to take in the HQs of the international companies that are worried about the Brexit, and above all, France wants to compete with the City as an international financial market: "although we feel that London will do everything it can to remain the world's leading financial market, it is good policy for competing markets to prepare to take advantage of the Brexit (...) Paris wins over its competitors."[17]

France is worrying. French President Emmanuel Macron, a convinced pro-European, is quick to stress his ambition to revive Europe, he is sometimes presented by the British press as Machiavelli or Napoleon, and is felt to be a threat to British interests in the Brexit negotiations. The day after his election Boris Johnson, the Foreign Minister, and a supporter of a hard Brexit, wrote to the members of the Conservative Party to ask them to strengthen Theresa May's position in order to make a strong stance against France. The European Council of 20th October 2017 devoted to the Brexit revealed quite an aggressive position. During the press conference the French president deemed that "those who were advocating Brexit had never explained what the consequences were to the British people." The UK is still "far off the mark" in its financial commitments, (...) "all around there is noise, bluff, fake news (but) we haven't even gone half way yet." France does not "want to punish" but it is clear that it has some budgetary requirements.

However, from a budgetary point of view France is not in the worst position concerning the British withdrawal. It bears the greater share of rebate (26% on average over the period 2010-2017) which represents a burden of 1.45 € over the last three financial years. Brexit will also mean the end of the rebate and therefore a potential point of saving. Brexit must neither cost nor take away anything from the other Member States. This is the French position. France is counting on an alliance with Germany. In spite of the customary friendliness, nothing is certain however. The interests of both countries are converging, but do not overlap.

2. The bill until 29th March 2019

Normally until 29th March 2019, nothing will change. And yet with the Brexit everything is becoming complicated. Three factors have to be pointed out. The main issue involves the clearance of the accounts via commitments outstanding.

2.1 Clearance of Accounts: Commitments outstanding

This is the main position in the exit "bill". Although the Union does not have any debt[18], it has accumulated significant payment arrears as the years have gone by: the commitments outstanding (RAL) which correspond to the commitments in the European budget that have not yet been covered by payments. "Anyone who takes an interest in European questions (knows) that there is a ruffle in the European funds that has to be liquidated, budgeted, unspent, which is vital for the EU because (...) we do not know how we are going to overcome it."[19] One day or another this bill will have to be paid. Via a loan? By the corresponding payment appropriations? The total is decreasing, but these RAL are still said to represent 251 billion € at the end of 2017[20].

The UK, like any other country has to take part in the clearance. But on which basis? On the national GNI or on the base of contributions?[21] On the base of the GNI's in years of commitment or on the base of present GNIs[22]? There are significant differences and given the base, each 10th of a point after the decimal point can be calculated in billions of €. This arbitration will be decisive in assessing the bill.

2.2 A reduction in the British contribution due to its wealth effect

The notification of Brexit triggered a procedure and a withdrawal negotiation but until the country leaves it is still a full member of the Union. No one is challenging this situation[23].

Initially the Brexit will not therefore have any immediate budgetary impact. The country takes on all of the costs of it belonging to the Union with the rules in force (contributions, rebates, returns). Brexit will lead to neither additional costs nor reduced resources for the other Member States. Some unplanned events might occur and be burdensome to the Member States.

2.2.1 The impact of Brexit on the British economy

The wealth effect

British growth has slowed and this is affecting its contribution. Over the last ten years the UK has grown faster than its partners: 1.1% on average per year between 2006 and 2016 against 0.5%. This differential is now reversing. Although the announcement of the Brexit did not lead to a collapse in activity, it is now established that it has weakened the British economy. Many estimates leading up to 2020 range from between +1.5% and - 9.5%. The mid-term estimate lies at - 2.2%[24]. The economic consequences of the Brexit have started to emerge in 2017. The growth rate is said to have dropped to 0.7% (against 2.2% in 2015 and 1.8% in 2016).

The States' contributions to the European budget, whether this is via the VAT resource or the GNI, are entirely linked to the country's activity and its wealth. Hence the British contribution is due to decline. This is not a stalling tactic, but the simple arithmetic effect of the slowing of British growth on the calculation of national contributions. This decrease is all the more significant since levies are adjusted retroactively.

The monetary effect

The British contribution is also affected by the monetary factor. Pound/euro parity has dropped since the announcement of the Brexit. The British will have to pay more in £ if they have to assume their contribution in €. But some sources believe that this decline will lead to a 1.8 billion € loss from the European budget[25].

2.2.2 The budgetary impact: increase in contributions by the other Member States.

The decrease in British contributions leads to an increase of the other States' ones. The financing of the European budget is interconnected. Since revenues adjust to overall spending, any reduction in revenue is financed by the others. A reduction on the part of one State is compensated by an increased contribution by the others. The Greek precedent is a perfect illustration of this phenomenon[26]. The difference between the timid recovery of activity in the euro zone and the slowing of British growth, partly due to the Brexit will reflect in increase of the contributions by the 27. This will reach a peak in 2019 when the 2017 figures become final.

2.3 The resulting costs.

Finally, the Brexit will lead to some specific spending directly linked to the British choice. This spending is however quite marginal. Two posts have often been discussed.

2.3.1 Spending on Staff

According to article 28 on the Union's Staff Regulations, "no one can be appointed an official if he is not a citizen of one of the Member States of the Communities." Around 2000 Britons[27] work in the European institutions (60% at the Commission, 40% in the other institutions) to which we had to add 600 people if we include agency personnel. These officials will have to leave the institution. Some exceptions "granted by the appointing authority" will be possible but they will be rare. The regulation lists the cases of termination of service[28]. It is likely that the corresponding authorities will know how to arrange the terms of departure. Local agents will be invited to leave, some officials will become young retirees. The matching spending will therefore increase sharply[29]. The pooling of the pensions burden of former British officials, whether this involves those already retired or those who will retire due to Brexit, will be a point of negotiation. The same will apply to the British MEPs.

2.3.2 The practical consequences affecting the organisation of the European system

The Commission has established a list of 67 bodies that will be affected by Brexit. The most obvious of these are linked to the transfer of the HQs of two decentralised agencies from London, the European Medicines Agency (897 people) and the European Banking Authority (154 people). The European Union deems that the entire cost of the transfer (move and re-establishment) should be borne by the UK.

The financial impact might go in the other direction and the UK will ask for a share that matches its relative weight in the Union's assets, notably the reimbursement of its share in the capital of the European Central Bank and its commitments in the European Investment Bank.

2.3.3 The consequences on the European legislative process

In the two-year interim period, although they will still be Members, the British will often withdraw from collective decisions, preferring to abstain or not to take part in the vote. This caution is relinquished when it comes to budgetary issues. As seen in the terms of the adoption of the MFF in June 2017.

For a while the UK blocked the revision of the Multi-annual Financial Framework 2014-2020 deeming that the British authorities could not give their opinion on such important issues during the electoral period (prior to the elections on 8th June 2017). The country finally withdrew its reservations regarding budgetary redeployment. Taking care to stress its constructive position and calling for similar fairness on the part of the 27 in the Brexit negotiation[30]. (The UK withdrew its reservations of the revision of the MFF) "In order to support the good governance of the budget while the UK remains a member of the EU, recognizing that the Mid-Term Review will have an effect primarily on the budget after the UK has left the EU. This is without prejudice to the UK's position on asserted financial liabilities in the forthcoming withdrawal negotiations, and conditioned on the clear understanding that the EU acting at 27 will not use the UK's constructive position on the Mid-Term Review to add to its asserted claims regarding UK liabilities. The UK is confident that other Member States and the institutions will reciprocate the UK's act of good faith in facilitating Union business primarily applicable after its withdrawal in the approach they take to the withdrawal negotiations, and in ongoing relations to UK businesses and recipients of EU funds. We expect that they will apply a similar sense of fairness, and work cooperatively on an orderly withdrawal." When billions are in play then the sense of fairness sometimes tends to fade away.

3. 2019 -2021, the most dangerous years

It will be as of 2019 that budgetary data of the Euro-British relationship will become singularly complicated. The country will cease to be a Member State (except if there is a postponement decided unanimously). It will only be tied by its past commitments and possibly those of the future. What are these commitments?

3.1 The gap between the Brexit and its budgetary transposition

Brexit will not reflect immediately in the budgets of 2019 or those that follow. It is a question of simple applying the Union's budgetary rules as they result from the financial settlement[31] and of any additional texts.

3.1.1 The payment of prior commitments

The first problem arises in the link between commitment appropriations (CA) and payment appropriations (PA). Even though a preliminary legal base is required, the commitment allows and justifies the spending. The CA defines the amount that is to be affected for the completion of an action. The PA defines the means that are effectively going to be paid in a given year. Hence in most cases the CAs in year n are covered by the PAs spread over several years (n, n+1, n+2). This is particularly the case with cohesion spending.

The country is a Member State until March 2019. So, it either takes part in the Council's votes, a constitutive element of budgetary authority (Parliament and Council), notably adopting the CA's and it is difficult to see how the country could not finance, in PAs, the appropriations that it approved just a few months previously in CAs - or it suspends its participation by not taking part in the voting for example. Hence budgetary choices would be made without it. Should the country finance the PAs matching the CAs decided by the 27? Of course, even if it suspends its participation the country will have to finance the PAs that match the CAs adopted by the budgetary authority, even if the payments take place after the Brexit. But the higher the CAs before the British departure, the more the country will be tied by its prior commitments. The 27 can try to "burden" 2018 and 2019 and commit to spending which might have been postponed to the following year, even if this were just to force the UK to pay the matching PAs. It has to be said that the period will not be an easy one.

3.1.2 The catastrophic scenario: if the 27 pay for Brexit ...

The catastrophic scenario is linked to the retroactive calculations of the GNI contribution. The Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States is used to calculate the greater share (72%) in the European budget. The GNI is therefore a fundamental economic aggregate. Any over or under estimation of a Member States' GNI even if it does not affect the GNI's own resources overall, it does reduce (or increase) the respective contributions of the other Member States. The same applies to the revenues made via VAT. Assessment procedures are therefore extremely precise and monitored[32]. The estimates given by the States are checked, adjusted and revised[33]. The assessment process and modifications can take several months. A regulation from 2016 organises this procedure and takes the time span for adjustment to four years[34]. Hence changes in growth in a Member State affect contributions, but adjustments are retroactive over four years.

Hence, quite logically, the slowing in British growth will affect the contributions of the 27. If this slowing is greater than what was first forecast, contributions are re-adjusted: the country's contribution decreases retroactively and the contributions of the 27 increase retroactively. This leads to the most catastrophic hypothesis for the 27: that the 27 will have to reimburse the surplus paid by the British. In other words, the 27 will have to pay for the Brexit!

This is not a completely fanciful hypothesis, since via the retroactive adjustments it has happened that the UK has become temporarily a net beneficiary! Breaking with the years of net contribution, in 2001 the UK recorded a net positive balance of 955 million €.

3.2 The link between the British withdrawal and budgetary planning

3.2.1 Brexit and the end of the Multi-annual Financial Framework

The 27 have a clear, simple position: the budgetary commitments made as 28 must be adhered to. What are these commitments? The main one is linked to the Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF), the keystone of the European budgetary system. The MFF is adopted by the Council after Parliament's approval, but in fact the Council takes up the arbitration delivered by the European Council after months of negotiations. Of course, the UK has played its part in this negotiation and in the arbitration. The MFF adopted in 2013 is applicable until 2020, and even rather 2021, given the time taken to implement the future MFF. After 2019 the legal nature of the MFF will be crucial in relations between the EU and the UK.

Does the MFF bind the country? In spite of a united front (amongst the 27) there is uncertainty about this. The MFF is sometimes presented as a budgetary planning tool. Undeniably it does bear some features of this, notably a table that lays out the commitment appropriations, per theme and for each of the seven years of the MFF (2014-2020). In its communication, the European Commission speaks incidentally of program and planning[35]. But the TFEU provides another definition.

Article 312 TFEU:

1 The multiannual financial framework shall ensure that Union expenditure develops in an orderly manner and within the limits of its own resources (...).

3 The financial framework shall determine the amounts of the annual ceilings on commitment appropriations by category of expenditure and of the annual ceiling on payment appropriations. The categories of expenditure, limited in number, shall correspond to the Union's major sectors of activity.

Neither of the terms "orderly development" nor "ceilings" mean spending commitment - nor do they in the legal sense (the commitment appropriations are set every year by the budgetary authority) or in the political sense. Of course, the MFF is a planning and forecasting factor in the sense that it directs the total and structure of the European budget; of course, the MFF sets the budgetary framework and provides a view of the Union's major budgetary orientations, but the MFF only sets the spending ceilings that must not be exceeded[36]. The annual budget, its exact total, in CAs and PAs, just like its distribution, down to the last detail, are still set by the budgetary authority (Parliament and Council) according to a special legislative procedure, but which is based on the co-decision of the two branches of the budgetary authority.

Several hypotheses are possible.

- The first is to adopt (without the UK) an annual budget to a total that is below the "provided" one for by the MFF (adopted with it) to take on board the British withdrawal. Since the European budget has to be below the ceilings, the withdrawal of a Member State is equal to a choice on the part of the budgetary authority. This leads to a decrease in spending paid out to the Member States.

- The second is to adopt a coherent annual budget with the total provided for by the MFF, which leads to an upkeep in spending, but also a rise in contributions by the 27.

- The third option is to revise the MFF, which sets a rigid budgetary framework for the Union, by defining the spending ceilings per theme and year by year. The 2013 regulation setting the MFF for the period 2014-2020 does include three flexibility factors however: the special instruments notably designed to respond to emergency situations, flexibility in the distribution of appropriations between themes, and the revision of the MFF. The latter, which has to be distinguished from the adjustment to real prices, is provided for in several instances:

- the mid-term revision, provided for in article 2 of the regulation: "before the end of 2016 at the latest, the Commission will present a re-assessment of the functioning of the financial framework, taking full account of the economic situation of that particular moment"

- revision to adjust the management of the appropriations in the structural fund;

- revision linked to the implementing conditions to adjust the development of the PAs and CAs

- revision in the event of a revision of the treaties;

- revision in the event of enlargement;

- revision in the event of Cyprus reuniting.

Brexit is not part of any of these scenarios.

The mid-term revision was adopted by the Council on 20th June 2017[37]. At no point in time, except on the occasion of voting explanations in Parliament, has Brexit been mentioned. The negotiation of a new MFF for the period 2021-2027 (?) will be opened by a Commission proposal expected for 2018.

Once the mid-term revision was adopted in 2017 and that the negotiation of the future MFF is launched in 2018, the hypothesis of a further revision of the present MFF can be ruled out. In all events it will imply the unanimity of the Council.

The fourth is the postponement of the withdrawal of the UK, even this was done so that the exit of the country coincided with the end of the MFF. This would suit the 27 quite well, but objectively it would place the British in a position of strength, which might take advantage of this to negotiate a reduction of its budgetary debt vis-à-vis the Union.

The reference in the MFF to "oblige" the country, to force it to pay until 2021 does not seem to be most adapted. This does not mean that the Union will find itself diminished.

3.2.2 Extra MFF budgetary planning

The MFF is the keystone to the European budgetary system. But nearly all of the actions and programmes go together with financial programming documents. A financial sheet is even obligatory for any proposal that affects the budget. This obligation is provided for by the financial regulation[38]. Programming can involve entire policies, such as the cohesion policy or the research and development framework and other programmes like LIFE, MEDIA etc. Hence, budgetary planning can feature in a basic legislative act or in one of the Commission's implementing acts[39]. In both cases the country is an integral part of the decision-making process or as a member of the Council, co-legislator, (with Parliament), or as a member of the expert panels consulted by the Commission.

For example, in an implementing act the Commission (resuming the arbitration between the Member States formalised within the committee of the Member States), has defined a precise breakdown year by year, Member State by Member State, almost down to the last euro, of the allocations of the various structural and investment funds[40]. In this case the budgetary commitment of the 28 is quite clear.

Hence if the MFF does not seem to bind the UK in itself, the legislative acts together with budgetary programming documents commit the European budget and, as a result make it obligatory to finance the Member States' share and that of the UK in particular.

This it seems is the source of the cost. This obligation means detailed work in terms of exhaustive documentation of the budgetary programmes planned before March 2019.

Is the position of "nothing more, nothing less" tenable? "Nothing more" means that the 27 do not have to pay in the place of the British, and "nothing less" especially means that the beneficiaries of a programme must maintain the total that was planned as 28. This means that the country will continue to pay its share of own resources (contribution to the budget). This is quite an understandable position on the part of the 27 which does however highlight a sizeable weakness: the country would continue to pay for the others in virtue of its previous commitments, but would cease to benefit from the European budget, since it would have left the EU. This solution would be seen as a provocation on the part of the British, and might lead to worse solutions - Brexit without an agreement.

3.3 The future of customs duties

Even though they are just a minor resource in the European budget, customs duties will be affected by Brexit. The final balance (loss or gain?) depends however on two details that are difficult to perceive ahead of time: the development of trade and the existence or not of a trade agreement between the EU and the UK.

3.3.1 The development of commercial transactions

Anglo-European Trade

Internal trade is due to be the most affected. Brexit re-introduces procedures, administrative costs, which significantly impede trade. Even in the event of a trade agreement, Brexit will slow commercial transactions possibly up to 25%.[41].

However, from a strictly budgetary point of view if there is no specific trade or customs agreement, the UK will become a third country, with its imports being subject to the Common External Tariff (CET). Hence customs duties will become a reality[42].

Anglo-World Trade.

Brexit will also go together with a redirection of international trade. The country is already more oriented to the rest of the world. Trade with the EU represents less than half of its trade. Customs duties on imports would then be counted as a national revenue. But what will the attitude of non-European operators be who choose to export to the UK? A share was destined for the British market and there will be a loss of revenue on the part of the Union. But a share was also destined for the European Single Market. If non-European exporters choose the UK for convenience sake and because the country gives access to the Single Market, it is likely that some of them will opt for another point of entry. Customs duties lost in the UK will go elsewhere (the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, France?). Revenue losses will be reduced by as much.

3.3.2 The negotiation of a trade agreement

The key to this lies in the establishment or not of a trade and customs agreement between the EU and the UK. There are two possibilities: an EFTA type free trade zone or customs union[43].

The country does not want Customs Union with the EU (which means a common external tariff - CET) and counts, on the contrary, on a British trade offensive towards the rest of the world, including on an advantageous customs tariffs in comparison with that of the Union. Some supporters of a hard Brexit deem that the exit of the Union even provides an opportunity to develop trade without having the impediments of the CET customs barriers.

But it is difficult to forecast trade relations with the Union without this including specific treatment. Can we imagine a return of the borders between Ulster and Ireland? Can we imagine Airbus paying customs duties on the wings of the planes made in Wales? An agreement of this type obviously changes the amount of customs duties created by commercial transactions. If there is no agreement, international trade rules provided by the WTO will apply.

3.4 The upkeep of budgetary contributions linked to partnerships

Brexit does not mean the end of budgetary contributions. It is likely that the country will remain a co-financer of some spending

3.4.1 The "obligatory" programmes

The British withdrawal from some programmes seems difficult, notably in the international area. This is the case with the "facility in support of the refugees in Turkey"[44] and even the European development fund, a budgetary tool of European aid to developing countries[45]. It is likely that the country will not take the political risk of a brutal disengagement regarding these two politically sensitive programmes. Participation in the dismantling of nuclear power plants in some new Member States might also be negotiated with ease[46]. These various posts are part of the requests made by the 27.

3.4.2 A partnership agreement

More generally it is likely that the EU and the UK will negotiate a partnership in certain European activities and programmes like the cooperation agreement the Union has with Switzerland and Norway. The UK will want to benefit from the advantages of the single market. "It seems difficult to foresee that the up-keep of high integration on the part of the UK in the single market will be possible without a financial contribution being asked of the latter, as is the case for example of Switzerland and Norway," deems Albéric de Montgolfier[47]. These agreements have a budgetary chapter. The Senator sees in this "a counterbalance to their access to the single market." Even if the result is the same, it is likelier that these countries will not take part in the cost of access to the single market but to certain specific European programmes, notably the FRDP and university exchanges. Without being partners in the cohesion policy (-which involves all Member States) these two countries pay a contribution to the development of countries which joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013.

Switzerland (bilateral agreement) for example, contributes to the following: FRDP, new members aid, European aviation safety agency, the European environment agency, Erasmus, Galileo. Together these represent an annual contribution of around 730 million €[48].

Norway (European Economic Area) has twice refused to join the European Union but relations are extremely close. Particularly from the point of view of the budgetary plan. Without being a member of the EU Norway pays nearly as much as if it were one. It makes major contributions to the FRDP and is involved in many European programmes[49].

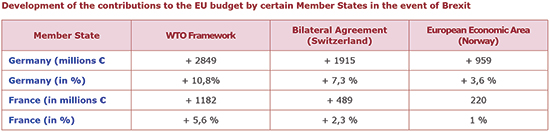

This chapter was taken into account in the Senate's report. The sums at stake are of size. A partnership according to the Norwegian model would maintain it almost at its present level (given the rebate). The effect would be extremely significant on the Member States.

Source: Albéric de Montgolfier, French Senate n° 656 (2015-2016)

Source: Albéric de Montgolfier, French Senate n° 656 (2015-2016)

***

The budgetary negotiation stands as a multi-facetted kaleidoscope, RAL, MFF, commitments, agencies, pensions, etc., there are as many subjects of debate and opportunity as there are for friction. This is the very essence of the "bill" which explains the enormous range of the estimates regarding the cost of the Brexit, which range from an upper figure of between 0 and 100 € or more modestly between 20 and 60 billion€.

After 2021, the situation is due to resolve. The bill will be issued (unless it is settled) and the European Union will have a new MFF and new programmes. The UK will then obviously no longer be bound via European budgetary decisions, except for contributions to some programmes. The outlook seems clear. But is the situation really that simple? On one can be sure.

Part II

The Consequences of the Brexit on the budgetary policy and negotiation

The Brexit will not relieve budgetary tensions within the Union. They will suddenly flare up even, when the next multi-annual financial framework (MFF) that will focus on the period 2021-2027 (or 2025 if the duration is brought down to 5 years) is negotiated. Negotiations should open with a proposal by the Commission expected in 2018. The consequences of the Brexit on the Union's budgetary policy and negotiations will emerge in three areas: the level of the budget, its structure and the debate over the net balances and rebates.

1. The consequences on the budget's total: Germany will lose its best ally

For ten years the main focal point has been the overall level of the budget. It has been a bitterly debated issue and was finally arbitrated at 1% of the Union's gross national income (GNI) in the MFF of 2014-2020. But arbitrated by whom? Of course, from a formal point of view the MFF is adopted unanimously. But in the budgetary negotiation the States are not equal, and the main financiers and net contributors weigh more in the final decision. Hence Germany, the budget's lead financier has almost always been the decisive factor, but the UK has played a guiding role to limit the level of the European budget. With the Brexit Germany will lose an objective ally, probably its best budgetary ally.

1.1 The objective alliance between the UK and Germany

1.1.1 The decisive influence of the UK in the budgetary negotiation

The UK has always played a decisive role in the budgetary debates, notably on the occasion of the MFF negotiations. It has often been the kingpin in the anti-spending coalitions that formed even before the start of the negotiations. This was the case with the MFF 2007-2013, with the "austerity coalition"[50]. It was also the case with the MFF 2014-2020 with the "better spending"[51] coalition, in other words the States in favour of limiting the European budget. During negotiations the UK ramped up debate by presenting real proposals, it did so in 2005 during the six monthly presidency of the Council, presenting an MFF of 1.03% of the GNI, then again in 2012, asking for a reduction of 100 billion € in comparison with the Commission's proposal, then proposing a cut of 147 billion € , twice that of the measures put forward by the President of the European Council, notably via a reduction in spending on staff and a reduction of the share of the CAP in the budget, brought down to one third of the budget (against 42.5% in the previous MFF).

An offensive that was benevolently observed by the real budgetary decision maker, Germany.

1.1.2 Germany, master of the budgetary game

Shortly after this Germany put its own proposal forward, 1% of the GNI, 960 billion € "all inclusive" instead of the 1033 billion € announced by the Commission. This was indeed 1% and 960 billion[52] (in 2012's value)

Hence, Germany, the first financier, and leading net contributor to the European budget has almost always been the sole decision maker. Discreet, but the decision maker all the same. Without daring to offend its main partners (France and Poland) its interest however lies in controlling the budget. Germany sets the limits (1% of the GNI on average) and has its proposal for commitment appropriations (960 billion €) as well as payment appropriations (908 billion) approved by the other States, but the UK previously played a key role.

From a budgetary point of view Germany and the UK have always pulled in the same direction and have had the same goals. Their budgetary weight has been decisive and inevitable. They alone represent one third of the gross contributions but especially half of the net contributions: 100 billion in 5 years (2011-2015). When one puts a figure forward, the other puts forward a level in proportion to the GNI. There is perfect coherence (connivance) between the two countries.

The negotiations for the next MFF will open in 2018. With the Brexit the context is however extremely different. Germany will be the ultimate decision maker. Its interest remains the same: controlling European spending. The Chancellor would be taking too many political risks if she let the European budget go. An increase in the MFF, even if it were to be symbolic and limited to 0.1% of the GNI, would represent an additional annual contribution of nearly 3 billion €. Germany will not be Europe's "cash cow".

With the Brexit the European Union might lose 10 billion € per year. It will have to adapt either by maintaining the level of the budget by value and, as a consequence, by increasing both the States' contributions and the weight of the budget in the GNI by going over the famous 1% or by reducing spending. "Several States have already said that they do not want to increase their contribution".[53] But with the Brexit Germany will be losing a budgetary ally. Of course, it will be able to count on the support of other countries that favour the strict control of the budget (the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Austria), but their political and budgetary weight is far from equalling that of the UK. And this is without counting the particular case of France, whose role will become vital in the future.

1.2 France the next MFF arbiter?

France has always been embarrassed about European budgetary issues. Accused in the 90's of taking advantage of the system (thanks to budgetary returns from the CAP) it had to suffer the rebellion of its partners and had no other choice but to become a net contributor itself, to the same degree as the other countries of a comparable standard of living. This is now history. France takes on a greater share of rebates given to other States than the UK. As a result its budgetary situation vis-à-vis the European budget worsened as of 2010[54]. Hence it now has a budgetary interest to control the European budget.

But it has joined the camp of the anti-spenders out of strategy, to prevent coalitions being made behind its back, via a drastic reduction in aid to the first pillar of the CAP, a traditional priority of French farmers[55]. Moreover, we should not hide the fact that French Finance Ministry still believes that the levy of revenues for the Union[56] are a heavy budgetary constraint that weigh on the French budgetary balance which they try to minimise. The political/budgetary arbitrations (Finances + Agriculture Ministries against the political rationale of European integration) has led to embarrassed convolutions. When Bernard Cazeneuve, was French Delegate Minister for European Affairs he deplored the fact that France revealed itself during the budget negotiation to be "amongst the most miserly of skinflints," showing to the world "an authority negotiating cuts with the British of 200 billion €"[57] but accommodating himself perfectly with the reduction in the European budget once he became Minister of the Budget.

Hence in 2012 in preparation for the MFF of 2014-2020, France had no other choice but to accept the limit set by Germany. In fact, it could pretend to regret this even though behind the scenes it was not unhappy. The ritual accusations made against British intransigence regarding the rebate concealed true relief in fact.

Will France continue to play this balancing game in which it manages to have the best of both worlds, in other words, money and politics? On several occasions the President of the Republic has shown that he intends to revive European integration. But it is hard to see how this might be done with a budget maintained at 1% of the GNI. This time there will be Germany and its budgetary rigour and France with a clear ambition, but with limited means. In spite of the inevitable speeches of friendship and solidarity the two approaches are on a collision course. The negotiation of the next MFF will be a moment of truth, the next major meeting will highlight the power struggle between the two countries.

1.3 What room is there for progress?

Making an increase to the European budget is a recurrent demand expressed every time the MFF is in preparation within the political and academic institutions. We have to distinguish between what is desirable and what is possible.

The desirable depends on a political choice. Clearly a European which budget limited at 1% of the GNI cannot ensure all of the traditional budgetary functions (allocation, redistribution, and stabilisation). It does not reach the threshold that would allow it to be a true actor in the event of a crisis. Think for example that at the height of the financial crisis in 2007/2010, the European budget did not even total the budgetary deficit of France alone! The MFF is also a rigid framework, ill adapted to budgetary change and fiscal stimulus. From a political point of view the European budget does not match - or it does so very poorly - the needs expressed by public opinion. Although the Union exercises decisive influence in the environmental area via its legislation for example, it has practically no budgetary means. Hence the frequently expressed idea of a budget of 3% or even 5% of the GNI - a European budget of between 500 and 750 billion €.

An increase like this in national public finance and the pooling of financing with public opinion as its stands today, is utopic. Is it reasonable to believe that the German contribution to the European budget could rise from 24 billion to 100 billion €? And we must not forget that the decisions regarding own resources are adopted by the Council, unanimously and after ratification by the national parliaments. Quite clearly a budget that is doubled or tripled will not happen tomorrow.

This does not mean that there is no room for any increase if we remain within the present legal own resources decision-making framework which sets a cap on own resources at 1.23% of the GNI[58]. However, the cap on resources conditions the cap on spending. There is no institutional obstacle to the European budget reaching 1.23% of the GNI. The increase would remain under the cap and there would be no DRP (Distribution Resource Planning) subject to the ratification of the national parliaments.

This obviously means an increase in resources, whether this entails finding new own resources (a percentage of existing taxes, a tax on financial transactions, a new resource levied on energy imports) or increasing Member States' contributions.

If the 27 take on the British net contribution (i.e. 7.4 billion € on average) the European budget would rise to 1.23% of the GNI, i.e. exactly the ceiling set by the DRP. The Brexit is therefore an opportunity therefore to take this leap forward! It is in this sense that we have to understand that some observers also deem Brexit as a chance.[59]. Are the Member States prepared to make this choice? The negotiation of the next MFF will witness a confrontation between two visions of Europe.

2. The consequences of Brexit on the structure and content of the European budget: towards a posthumous victory for the British?

On 28th June 2017 the European Commission published a concept paper on the future of the European Union's finances[60]. This document stresses the imperative to mobilise European appropriations in support of vital Europe-wide policies (cohesion, food aid, scientific and technological projects, major investments) and the need to rise to new challenges: encouraging sustainable development, responding to the migratory crisis, fighting to counter terrorism. "Even more than the previous reforms, there will be a strong temptation to achieve further room for manoeuvre to the detriment of the European Union's traditional policies"[61]. Brexit will simply heighten tension and lead to a change in direction of the two major European budgetary policies: the Cohesion Policy and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

2.1 The consequences for the Common Agricultural Policy: towards a posthumous victory for the UK?

British opposition to the CAP is resolute and constant. Farmers do not feel any great regret about the departure of the UK. We should not expect upheaval regarding the CAP even though there is every reason to believe that the next CAP will certainly be more in line with the British view of things than the French. This will be visible both at the budgetary level and in terms of the CAP content.

2.1.1 The CAP global budget

The Commission's positions in its concept paper are all striking signals of a determination to erode the total amount granted to the CAP and its share in the European budget.

On this issue some observers have always played on ambiguity. Up to now reducing the budget in value has always been deemed politically impossible to assume. A constant envelope reduction has taken place but in current €[62]. This operation is insidiously leading to a discreet but regular reduction of the share of the CAP in the budget. But although the CAP is no longer the budgetary colossus of former times, it will still be consuming 38% of the budget over the period 2014-2020. It is clear that this share might suffer a further reduction in the future period of budgetary programming.

Will France support the CAP and its budget as it has done in the past? Contrary to popular thought, France is not the only one in this budgetary battle. As structural aid has gradually decreased the CAP has increasingly represented a major budgetary stake for some States. For five years Spain has received more European subsidies in virtue of the CAP than structural funds. Poland and Romania receive major sums of aid and have become influential backers of the policy.

But French support might not be as clear as it used to be[63] and pressure to reduce by France's main partners will not be lacking. The development of the CAP has been undertaken in an insidious manner to date. A more open offensive in the next MFF cannot be ruled out with a nominal reduction of the CAP. The goal of one third of the European budget, at least at the end of the programming, although it has been declared by no one, is on everyone's mind. The UK will have succeeded in something that it failed to do to date.

2.1.2 CAP content

The British have always had a major influence over the CAP's content. In the opinion of the Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan "the UK's successive ministers have influenced the development of the CAP in a positive manner, insisting on a stronger trend towards the market, on the protection of the environment and on a wider rural development policy."[64]

These developments will continue. We cannot expect a major reform. Even though, little by little, the CAP's content is transforming radically, the reform of the CAP is often just a progressive shift. The same will apply the next time. Again, a CAP that is more in line with the British idea seems now to be emerging.

The Commission's concept paper recalls the imperative to reform the CAP via improved targeting of direct aid, especially in the peripheral zones and in support of the poorest farms. It mentions the possibility of providing national co-financing to finance direct payments, a solution rejected in previous reforms. It advocates five possible scenarios for the period 2021-2027: a scenario of continuity, one of contraction in common action, one of voluntary based cooperation development, a scenario of radical reform and one of increase.

Except for the highly unlikely scenario in which the budget would increase, the European Commission plans to devote less resources to the CAP targeting spending on farmers who have particular constraints (mountain areas, small farms), on investment aid in rural zones, especially in support of agro-environmental measures and support to risk management instruments. In the scenario of radical reform the European Commission is even planning a drastic reduction of direct payments.

The CAP's structure will remain as it is, more or less. Several countries like France and Germany are adapting to the situation and want to maintain their direct aids - even though there is "packaging", presented as a "reform" as per usual.

We should expect a shift again between the first pillar (direct aid) and the second (rural development). This shift is not the best for the farmers who have always privileged a budgetary approach to the CAP and have often been behind in the agricultural battle. It is likely that animal well-being will be one of the new priorities in the next CAP. Others know how to anticipate societal developments better and do not need the CAP to respond to this. This development matches the UK's expectations[65].

2.2 The consequences of the Brexit on the Cohesion Policy

The Cohesion Policy[66] is the budgetary expression of solidarity between the Member States. This policy entails aid in the shape of massive investment subsidies[67] (approx. 350 billion € to each programme), it is generous (up to 10 billion € per year in Poland), the focus of a consensus (what a contrast with the CAP!), open (all of the States benefit in one way or another) and when it is well supported, it is often effective. The exit of the UK should however lead to strategic thought on the Cohesion Policy and probably a change in direction of the latter. The financial stake is enormous for the Union and for the beneficiaries for whom the structural funds are a major source of financing[68].

2.2.1 The statistical effect of the Brexit

The Cohesion Policy aims to "reduce the differences in the development of the regions." The intensity of European aid, both in volume and levels of co-financing varies according to the wealth of the region in question with a strong focus on the least developed regions. The index which is used for this ranking refers to the average GDP per capita[69].

In the same way that the 2004 enlargement led to a reduction in European average wealth due to the addition of countries that were far less prosperous than the old Member States, the exit of the UK will have the same effect, but this time via the exit of a State, which over time has become, both due to its own dynamism, as well as to the reduction in the European average revenue, one of the wealthy countries[70].

The exit of the UK will lead to a reduction in the overall GDP/GNI and the average per capita GDP/GNI. This reduction lies at around 3.6% i.e. around 1000€. This reduction will have a direct, mechanic effect on the aid that Europe provides to certain regions. Hence some regions that are on the threshold of eligibility of two categories receiving the most aid, in view of the most recent statistics (the least developed regions and regions in transition), will change category. This statistic effect involves twelve regions[71]. Even though the Union has experience in this type of situation and has adopted a transitory, digressive aid system, but which has remained generous, this new statistic effect cannot be ignored.

2.2.2 Changes in direction of the Cohesion Policy

The exit of the UK opens up three paths. The first hypothesis regarding the pressure placed on the main beneficiary countries, the European Union will maintain the present level of its overall packages (350 billion € in 7 years), which will lead to an increase in the Member States' contributions. This option seems highly unlikely. It is more probable that the Brexit will lead to a reduction in the budget devoted to the regional policy. The adaptation of the regional policy to the reduction in appropriations will be made either by a reduction in provisions made to the present beneficiaries or by a reduction in the number of beneficiary regions.

Reducing aid to beneficiaries? Budgetary aid from the cohesion policy represents a major source of support for the main beneficiaries and the old Member States, and their interest lies in the resulting and financial returns[72]. With the exception of the scarce observations of the European Court of Auditors[73], no one has ever dared to criticise this policy. Europe has never dared confront certain powerful beneficiaries in view of a reduction. During the MFF negotiation in 2014-2020 Poland vehemently defended the overall package granted to it by this policy. And yet are all investments relevant? When the EU grants several billion € per year to a country it is not unseemly to ask the question. Budgetary constraint might provide the impetus that has hitherto been lacking. It is likely that a certain number of countries which have been generously provided for to date will see a reduction in the sums granted. Negotiations will evidently be extremely tense.

Reducing the number of beneficiary regions? Although it is focused, the cohesion policy benefits all of the States and practically all of the regions - including the wealthiest. It is not surprising that all regions, the main beneficiaries of the structural funds (and co-financers of the operations undertaken), are its most ardent defenders. The Union represents "a financial windfall that certainly should not be allowed to pass by"[74]. However, we might ask whether the wealthy regions really need this European money[75]. It is not a question of whether co-financed operations are useful or not but to know whether the intermediation of the Commission is useful and necessary and whether the subsidiarity rule applies. In other words, should we not keep the cohesion policy for the priority regions alone, with a threshold that still has to be set, equal to 75% or 90% of the average for example?

The UK spoke in support of this path, but it always came up against strong opposition. Over time the EU has become both a major financial partner of the regions, a budgetary return policy for the States, one of the best pedagogical tools. For the Commission, which suffers a lack of legitimacy, the regional policy is a means to finance real actions in the daily lives of the European population. Several countries support this generalist vision. It is notably the case with Germany and France which deem that although the cohesion policy should be reserved for the poorest European regions, it must not be reserved for them alone. This policy expresses shared solidarity for future battles - energy and climate for example.

But at the risk of destroying a consensus and coming up against strong opposition, the reduction of appropriations will certainly force a change. Reserving the structural funds for the priority regions alone, as proposed by the UK, will lead to the suppression of aid to the present beneficiaries[76]. This idea might find support amongst some countries. The creation of a cohesion fund in 1994 bowed to this logic[77]. A rift will emerge between the so-called rich and poor countries. It will be a difficult point in the negotiation of the upcoming MFF.

2.3 Brexit and the other policies

2.3.1 Brexit and the research and competitiveness policy

The competitiveness policy is the new European credo. From the budgetary point of view, the European Union has artificially increased this policy in the MFF by including the cohesion policy, but the core is still research, via framework programmes for research and development (FPRD). The 8th FPRD covers the period 2014-2020. This policy is fundamental not only via the ambition that it supposes but also because Europe proves its worth this way. Whilst other major policies are in fact simply redistribution tools, the research policy is based on cooperation between researchers, research centres, businesses and between Member States. The European research policy (with other exchange programmes, like Erasmus) builds Europe up more than any other policy.

This policy has always been defended by the British. Just before the British referendum David Cameron listed his European demands amongst which featured competitiveness. He wanted it to be included in the entire EU's DNA, "to improve the competitiveness of the Single Market."

In this area the UK holds an excellent budgetary position[78] in which it has a great deal to lose. But for the Union it is also a major loss. International cooperation in the area of new technologies and research supposes a mix between strong, experienced partners, who have major capacities and who form the base of cooperation projects with more modest partners and those from candidate countries. The UK lies in the first circle. Scientific cooperation projects are obviously not impossible without it, and it will be missed.

The exit of the UK will make cooperation projects more difficult, but it should not lead to a major budgetary change. It is likely that the provision made to competitiveness will increase in line with what has happened over the last ten years. Although this was not a specific British wish it also matches a general trend that it supports.

2.3.2 The other policies

If we think along the lines of the present budgetary framework Brexit will only affect other areas, which do not represent any real budgetary weight, very slightly. Spending in other policies is marginal. The UK has always spoken in support of massive budgetary cuts, notably regarding spending on running costs. In 2012 D. Cameron tackled staff spending[79], but provisions are weak and margins even more so. The same goes for external spending. It is even likely that the country will maintain a share in its contributions.

At the end of the day it is a budget that is closer to the British vision that is now emerging. It is in this sense that we might forecast a posthumous British victory.

Unless that is there is a leap that would mark a break - because Brexit is also an "opportunity", in other words, a chance to revive European integration, to innovate, to fill in the gaping holes in the areas of environment and security. Instead of trying to satisfy all of the expectations that do not match the Union's key competences (healthcare, education and sport), to all of the debates and all methods - at the risk of spreading itself too thin, the Union might be able to focus on what brings true European added value, by financing operations which would quite clearly be better addressed at European level. This is what is really at stake in the MFF without the British.

3. Debate over the rebates. The European Union will be losing its scapegoat but the question of net balances remains[80]

The third budgetary issue that is still kept quiet, because it is the most embarrassing, is that of the rebates. The Brexit marks the end of the British rebate. At last! The European Union will finally be able to function without contortion/adjustment and a simple rule will be implemented: each State contributes to the European budget in proportion to its weight in the total GNI. This is the principle of the GNI resource, the budget's main resource. Does this mean the end of the rebates?

3.1 The present debate

The subject is still taboo. The rebates are decided after the definition of the net balances, calculated by the difference between the returns, the European budget spending in the country and its contribution to the budget. This calculation highlights a distinction between the net contributors and beneficiaries. An excessive imbalance means that there is a possibility for an adjustment.

It is taboo and certainly the greatest of European hypocrisy. The calculation of net balances is hypocritical. Never talk about it, but always remember it - since we have to admit that all of the countries do this calculation, notably when the grand negotiation for the MFF is underway. The net balance explains the position of many Member States.

Three mistakes are currently made about this.

The first is to consider this calculation in a sordid manner only. Of course, this purely budgetary approach masks all of Union's economic and political aspects and advantages. This type of calculation is derisory and narrow minded and even indecent given the historic ambition of European integration. It might even be called a "poison"[81], which is undermining European integration. European federalist circles even suggest that any reference to net balances should be proscribed.

So be it. But it is absolutely possible to consider these calculations from another angle. Net balances, far from undermining solidarity express, on the contrary, true solidarity between the countries. Transfers are massive. 40 billion € are redistributed yearly and go from the eight or ten contributing States to the 18 or 20 beneficiaries after the intermediation of the European budget. The movement caused by the net balances are the primary vehicle of budgetary solidarity, and are even higher than the payments made by the structural funds alone. Two thirds of this redistribution is guaranteed by three Member States[82]. Two thirds are redistributed to five Member States[83].

The second mistake is to confuse rebate and fair return. The rebate has always been criticised on the wrong basis. On several occasions the British asked for a balance in budgetary flows.[84]. But contrary to a widely shared idea, they never received it. The adjustment that was introduced with the Fontainebleau agreement in 1984[85], did not aim to reach a strict balance between the UK against the European budget and that it withdraw, even though Margaret Thatcher's declaration leads us to think otherwise, but limit "an excessive budgetary burden". This is not the same thing. An adjustment, not a balance. The UK, in spite of its rebate, is still an important net contributor, the second after Germany.

The third mistake is to believe that the British were the only ones to adopt a position on this issue. In truth, many other States took inspiration from this and aimed to limit their budgetary imbalance vis-à-vis the Union. They demanded and achieved budgetary arrangements which were neither as strong or as visible as the British rebate, but which are none the less adjustments that aim to reduce their contribution. In the MFF 2007-2013, the final agreement included no fewer than 40 measures designed to increase returns or reduce national contributions of certain States. This was the condition for unanimity. Was the "giveaway logic", according to the expression at the time, really nobler than the rebates? There are always a great number of adjustments. The main ones are the reductions in contributions of Member States in the financing of the British rebate.

3.2 The difficulties of future debate

Brexit will do away with the scapegoat but it will not get rid of the problem. On the contrary, we might even say that Brexit will complicate the settlement of the budgetary issue. This observation is based on the theory that the attention the States pay to the net balances remains. We might always "ban" these calculations, delete the Commission's tables in the annual financial tables, all of the contributing States will do it in their own corner anyway - using calculation methods that are not homogeneous and which will probably worsen the view the States have of their budgetary position.

Everything rests on the idea of an excessive imbalance. The idea has not been defined. What is an excessive imbalance? An excessive imbalance is deemed as such by the State that puts this argument forward. And it puts this argument forward in three situations. Firstly, by taking into account its relative prosperity. Then in comparison with comparable countries. The rebellion by several States against France at the end of the 1990's cannot be explained otherwise. Some States found it difficult to accept that France, a country as prosperous as they were, was a beneficiary in the European budget, whilst they were net contributors. Finally, and above all, the question is budgetary but the perception of it is political. The passage over from a situation of net beneficiary to the situation of net contributor can modify this view (the case of Finland). Conversely some net contributor States have never commented on it (Italy). The political climate surrounding Europe shapes budgetary position. The combination of these factors provides the precision of the Fontainebleau agreements with its full meaning: an adjustment - "when the time comes."

Although Germany is always discreet about this issue and even though the time for major criticism is over[86], the issue re-emerges from time to time, notably when it came to financing aid to Greece. It was out of the question for Germany to become "Europe's milk cow". There was a time when contributions were deemed excessive or in other words, when opinion deemed that enough was enough.

Finally, Brexit will complicate the issue a great deal. Because the main budgetary arrangements granted to the Member States all hang on the British rebate. The European Union has introduced several measures to reduce imbalances: reimbursements, reduced rates, targeted spending. But the best known and most widespread are "the rebates on the rebate" which comprise a reduction of the share of some States in the financing of the British rebate[87]. It is the rebate on the rebate that helps contain Germany's net balance, also that of Sweden and the Netherlands. Without the British rebate, no rebate on the rebate for the other States. Without the rebates the States will have to contribute in full, according to their share in the Union's GNI, and contributions will increase.

Sooner or later it is likely that this situation will be deemed worrying by those affected. With the British departure some beneficiary States might become net contributors. The situation in Spain for example might change. In Denmark, the Netherlands, Austria, in a context of increasing contestation against Europe it is possible that some States will consider that their budgetary costs are excessive.

Denying this can but lead to setbacks. It is likely that some countries will take initiatives on this issue at the next MFF. The European Union must accept this possibility and should prepare for it.

3.3 Some food for thought

There are several paths open to us.

Cutting back on transfers to net beneficiaries, by setting a limit on budgetary transfers. The principle of this kind of capping was decided before the last enlargements, during the European Council of Berlin in 1999. It features in the successive regulations of the structural funds. The present regulation of the structural and investment funds provides for a limit on annual transfers equal to 2.35% of the GDP of the State in question[88]. But although it will not be easily accepted, a reduction in these caps might be possible.

The overall capping of the net balances comprises the definition of a maximum net contribution level to the European budget. When this level is surpassed the surplus is transferred to the other States. This solution is regularly suggested by the Commission, but it is rejected by the Member States. Apart from the ritual positions of principle regarding European solidarity the variables in the calculation provide, as a result, numerous opportunities for bartering: which criteria should be retained? Contribution in % of the GNI, contribution per capita? Do we have to modulate these caps according to wealth, how should distribution be undertaken, caps only on the wealthy States, on everyone, or if a State rises above the threshold due to the financing of the capping of another? In spite of the opposition of the departments in charge of the States' budgets, this path deserves further exploration

The third possibility comprises modifying the structure of the budget to create greater balance in the returns towards the wealthy States. "The solution to budgetary imbalances means looking at spending" it was said when the British made their first request for an adjustment. Why don't we return to this sensible idea? Military and environmental spending would lend themselves quite well to this rebalancing. Against, it is the famous "opportunity" provided by the Brexit.

***

The level of the budget, its content and rebates are all issues in the balance of power between the Council and the Parliament and between the States. From a budgetary point of view the UK was a good scapegoat. The Brexit will be the hour of truth. To take up an expression from the Council in Fontainebleau "the time has come" to face these questions head on.

The Commissioner for the budget acknowledged that "budgetary negotiations with the UK would be difficult". Without it they will be all the more so. The French President announced after the European Council on 19th October 2017 that the UK had come half way. The 27 haven't started along their path.

[1] Methodological note: It is important to note long term data over at least three years, since variations from one year to another can be significant. These differences have to be explained. The EU's spending in a country is relatively stable from one year to another (except for the rise in cohesion spending for the Member States). However, the States' participation in the budget depends a great deal on the country's national wealth. The resources levied on VAT and on the gross national income (GNI) represent 82% of the financing of the EU's budget. Hence differentials in growth rate have immediate impact on the States' participation. A State with high growth will participate a great deal more in the EU's budget than another which has low growth.

[2] The net balance is not equal to the arithmetic difference between contribution and return. The States' contributions and the EU's spending in the countries are processed to apportion the country's administrative spending and a share of the customs duties that are collected. These differences explain the diversity in the estimates of the net balances. In the following part of this paper the net balances are taken from the Commission's calculations featuring in various annual financial reports.