supplement

Henri Labayle

-

Available versions :

EN

Henri Labayle

I - Overview

To establish this we need to recall some legal facts and decipher available figures.

1. The Facts

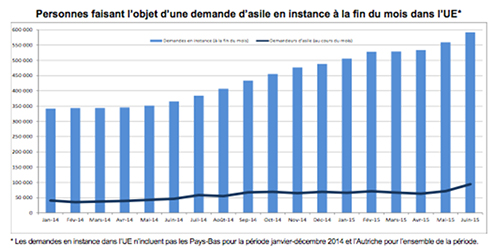

The figures are cruel. It is strange to see that they are analysed so little in terms of understanding the challenge facing European society. Over the last few weeks, and since their publication in the European Migration Agenda [1], graphics and tables of those asking for protection have been popping up everywhere, often incidentally, to lend credit to the idea that there is an unprecedented wave. This summary should be refined.

Analysing present requests for asylum is only rational if we put it into perspective with what already exists. Expressed in technocratic terms: thinking in terms of flows means analysing the stock.

However when the count is done an astonishing fact emerges: the Union does not have all of the instruments required to take measurements in spite of the quality of the work undertaken by Eurostat, which would enable it to base its decisions on an objective reality [2]. National reports, HCR, Eurostat, the European Asylum Support Office, Frontex and the NGO's, all diverge significantly. The complexity of the phenomenon, national and European systems that have been developed differently, definitions that are sometimes contradictory, reluctance on the part of the States to reveal their turpitudes, explanations are as multiple as they are abnormal.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

It might be better to speak of "trends", which unfortunately converge but are from the "invasion [3] that is often spoken of. However at the peak of the Syrian crisis in 2014 and 2015 the situation in the European Union worsened sharply. The number of requests for protection rose from 336,000 in 2012 to 626,715 in 2014. Eurostat's most recent figures reveal that at the end of June 2015, 592,000 people had registered a request for asylum in the EU. At the eye of the storm Germany is the preferred destination for asylum seekers, now totalling more than 50% of the requests.

2. The Law

International protection is a law which is as constitutional [4] as it is conventional. The reception of asylum seekers is not therefore a choice of opportunity, and assimilating them to ordinary "migrants" is a fundamental error. Reception is a legal obligation that has been decided by a judge.

The Member States of the European Union are individually and collectively obliged to honour the request of protection that is being made of them. On the one hand this is because the Geneva Convention of 1951 prohibits them from acting otherwise, notably by sending them back to borders where they are in danger, and on the other hand because the European Convention of Human Rights sets out the same rule, that has been sanctioned by its Court, and finally because the European Union guarantees the right to asylum in article 18 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

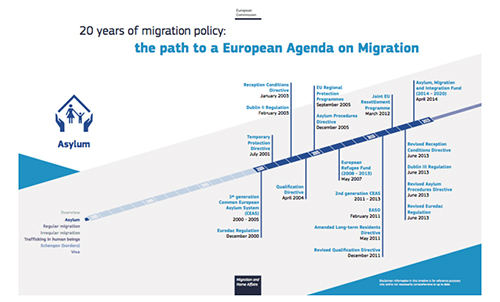

The States' sovereign powers as far as refuge is concerned are therefore singularly impacted by the degree of obligations that weighs upon them, notably because they are not allowed to shed responsibility onto possibly "unsafe" third States. This is an interdiction that relativizes the discovery of miracle solutions, whereby the problem is externalised. Apart from the guarantee of not being sent back, asylum seekers have the right to fair, effective asylum procedures and assistance that will help them to live. With these common obligations the Member States have adopted a common asylum regime. The second version of these texts governs procedure, reception conditions and qualification rules.

Source : Commission, 20 years of a migration policy : the path to a European Agenda on migration

Source : Commission, 20 years of a migration policy : the path to a European Agenda on migration

Hence the gulf between the facts and the law was striking at the end of the summer, and deadly for those who fell victim to it.

The dumping strategy adopted by the Member States in their management of asylum seekers has reached its limits however. The incorrectly named Dublin System, whilst inspiring the Schengen implementation convention, established the unique processing of asylum requests mainly taken on by the State of entry into the Union. This pushed most of the responsibility onto the Member States lying on the Schengen Area's external borders, to the utmost comfort of their continental partners.

Poor, like Greece, or not, like Italy, the latter took on this role as best they could in normal times. Even if this meant taking a few liberties with the respect of the Union's values, like Greece did regarding the reception of asylum seekers, or Silvio Berlusconi's Italy with its readmission policy into Gadhafi's Libya., These practices, condemned by the ECHR, but which contributed to a flawed solution collapsed with the geopolitical implosion that struck the Mediterranean basin.

Beyond this the common asylum system is affected by some major lacuna.

The first is due to the lack of any serious perception of the external dimension of the common asylum policy. It has been "political" in its first sense of the term, since Ancient times and when Churches were places of asylum. It implies the adoption of a position regarding the person persecuting, which in this instance has not been commensurate with the catastrophe taking place, either regarding the Syrian regime or those fighting him. German silence, French changes in position, British prudence, the cowardice of others - this is the deadlock the Union is in right now.

The failure of the Union and its Members' external policy is not without consequence. The protection of the person being hosted is indeed precarious, however if the threat weighing on the beneficiary is lifted then, ipso facto, there is no need for protection. Since the war in the Middle East, and in Syria in particular, is the main cause of the exodus, ending it is vital. Focusing attention on the return of illegal immigrants and remaining silent about the displaced is not a good policy - beside the fact that a new Palestine is now emerging in Iraq (250 000 refugees), in Lebanon (1 113 000 refugees), in Jordan (630 000 refugees), in Turkey (2 million refugees).

The second shortfall is a temporary one specific to asylum and the present crisis. There have been thousands of deaths in the Mediterranean, more than 3000 according to the HCR; those on the road through the Balkans are challenging the structure of the present asylum policy and bring a vital question to the fore: there is no legal path open to those seeking protection. This would mean them not having to risk their life to exercise a right, that of having their request assessed.

In other terms the European Union has exhausted a process in which it has tried to build a common policy, whose management it has left to the Member States, particularly those on the Union's external borders and whose external origins it has left almost unexplored. This reveals a deep internal crisis, triggered by the publication of the European Agenda on Migration proposing the relocation of people who have a clear need for international protection from Italy and Greece.

II - State of Crisis

The summer of 2015 and the pictures relayed by the media bear witness to this: a moral crisis experienced by the European Union went hand in hand with an institutional crisis that was visible to all.

1. A Moral Crisis

This was reflected in the Justice/Home Affairs Council's failure on 20th July to follow up on the Commission's initiative which proposed a binding "temporary, exceptional relocation mechanism." Unable to reach the symbolic figure of 40,000 people, the States opted for a "voluntary" solution of only 32,256 beneficiaries, together with a promise to add more in December 2015. On this occasion worrying lines of division became apparent.

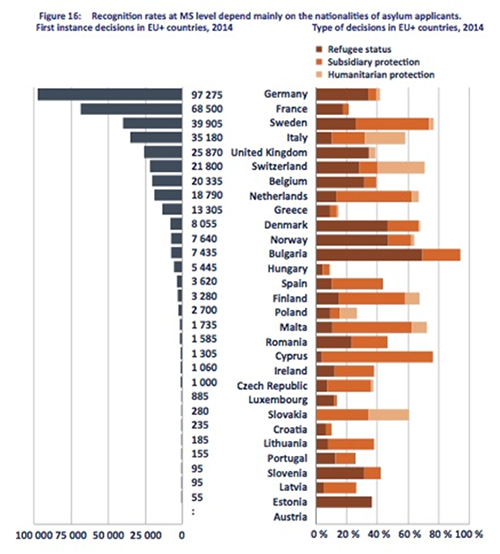

A front of resistance formed, whose delineation is easy to see if we look at Eurostat's national statistics: in 2014, Poland received 720 refugees, the Baltic States (Estonia 20, Latvia 25, Lithuania 75), the Czech Republic (765), Slovenia (45). If we add Spain and its 1585 meagre positive decisions, the picture is complete. Compared to that of Bulgaria, which has been overwhelmed (7 020), and the 8 045 positive Belgian decisions and the 30,650 refugees accepted by Sweden, this situation explains why there was deadlock at the beginning of the summer.

Source : EASO, Rapport 2014

Source : EASO, Rapport 2014

Courageously then, and alone, the German Chancellor took her responsibilities in August in two ways. First of all, politically, she stressed that the issue should be addressed above all, according to the principles and the values that found the European project; and then from a technical point of view, by deliberately worsening the crisis, as she linked the EU's impotence to the challenge being made to the area of free movement. The question was raised quite precisely in this area.

This position, which forced the truth out, revealed the silent opposition that separates the members of the Union regarding the migratory policy, and more precisely, the exercise of the right to asylum. The meaning and the scope of the terms in the treaty for a significant share of the Member States remain unfortunately obscure as soon as the "values" in articles 2 and 3 of the TEU are mentioned likewise "solidarity" in articles 67 and 80 of the TFEU. The abscess had to be burst.

Although these Member States are not strangers to migratory phenomenon, whether they have contributed to them in the west of the Union, or they are the focus of them from the east of the continent, notably from Ukraine and Russia, the cultural gulf that has developed due to their national histories has not been made good. Whether this in relation to the monitoring their external border, stolen by others for 50 years, or international protection in virtue of fundamental rights that are mostly foreign to their culture, the migratory debate has remained fairly theoretical from a domestic point of view and within their public institutions.

Action which was forced upon them by the crisis in July served therefore as a trigger, especially if like Romania they had been excluded from the Schengen Area by their partners over the last seven years. These States were increasingly defiant and rallied within the so-called "Visegrad" group. Led by Hungary they were joined by the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and more discreetly, they received the support of the Baltic States and Spain. On the defensive, they expressed their opinions and adopted stances that clearly challenged their inclusion in a project and common values. The fear of "invasion" and the promotion of the "Christian identity", the building of walls and behaviour by the police in the field raised awareness of the chasm.

With the disunion of the Member States, the explicit threat made by Germany to challenge the functioning and even the existence of the Schengen Area must be taken seriously. Designed for periods of calm, the Schengen system cannot withstand the battering of a major crisis, whether this involves penetrating the area - via the Balkans and the South - or even exiting it via Calais. Some of its main principles, notably, the Dublin processing of asylum seekers, may very well not withstand the test.

2. An Institutional Crisis

The Commission's position was not a simple one, in spite of the pro-active attitude of its president; such was the severity of the test it suffered regarding its capacity to assume its tasks in terms of migration.

In this instance the German authorities were again at work criticising the slowness with which decisions were being implemented and the curious impunity with which a certain number of States - from Greece to Hungary, not forgetting Italy - had wriggled out of their obligation to transpose and implement the common rules.

The choice of the legal base selected to draft the proposal to distribute asylum seekers did not reveal great determination either in coercing these States. By highlighting "an emergency situation typified by a sudden influx of citizens from a third country" which justifies "the adoption of provisional measures" and by temporarily derogating from the 604/2013 rule - the so-called Dublin rule - the legal base selected from article 78.3 of the TFEU, implies a simple consultation of Parliament, whilst §2 point c) of the same article identifies "temporary protection in the event of massive influx" as a constitutive element of the common asylum system and submits it to the ordinary legislative procedure.

Had the downturn in the situation not stopped the MEPs from entering a legal quarrel, there might have been conflict. In May 2015 the Union's institutions and the Member States had been perfectly aware for many a long month of the emergency situation and the sudden nature of the influx of asylum seekers as highlighted in the proposal. From Council of Ministers to European Council, the sinister litany of deaths in the Mediterranean were the cause of recurrent crises in the Union.

The essence of these points is of consequence and the taking of power by the States, reflected in Germany's leadership, meant that the Commission's role was reduced to that of executor.

The picture is hardly better in terms of the other protagonists, from the eclipse of a divided parliament, to the confused attitude of a President of the Council, whom we might have hoped to have been more concerned about the Union's values than public order. Jean-Claude Juncker's speech regarding the downturn in the situation was also much awaited, so that ideas to end the crisis could be set out. It proved to be salutary.

III - End of the crisis

Jean Claude Juncker's speech on the State of the Union on 9th September was merit worthy since it courageously moved into the terrain freed up by Germany. Of high quality, the path set out by the President of the Commission reminds each Union member of its past as much as its heritage and makes the choice of solidarity.

1. The choice of solidarity: emergency relocation

Before the summer the Commission had suggested relieving the States under pressure by relocating asylum seekers within the Union. Clumsily presented as "quotas" it first involved providing an emergency response, before the introduction of a long term mechanism. The violent arguments over the emergency mechanism in July and September have therefore been a rehearsal for a future battle that will take place when the final regulation, which has also been put on the table [5], is drafted.

There was another possibility based on the 2001/55, or the "temporary protection" directive of 20th July 2001. It is based precisely on "minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof." It presented the extremely political interest of asserting to a reticent public opinion that the protection granted is temporary, lasting between one and three years, even though the rights given to its beneficiaries are below those granted in terms of a normal asylum status and that it is difficult within the present situation to distinguish the Syrians from other nationalities covered by relocation.

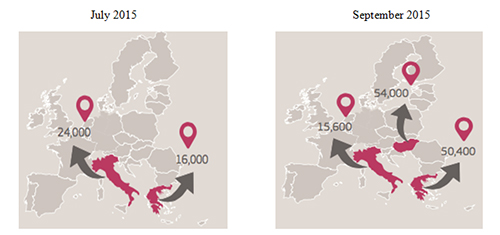

The Commission preferred to innovate proposing "relocation" in the shape of two Council decisions - one put forward before the summer [6] which targeted a total 40 000 people, before the crisis in September led a to second proposal of 120,000 people [7].

In both of these situations, there is a "temporary" derogation from article 13 §1 of the Dublin 604/2013 regulation in virtue of which Italy and Greece would be responsible for the assessment of international requests for protection. Their inability to cope with the situation explains why some States, like Germany, drew consequences by legally implementing their sovereign competence to acknowledge these requests as they opened up their borders - to the point that there is now a doubt about the survival of the Dublin system?

Since then the proposal for a permanent relocation mechanism proceeding to the modification of the Dublin regulation has supported this as recalled by the European Council. It remains that from a legal point of view derogating from a regulation in force on the grounds of an emergency and circumventing the powers of the parliamentary institution that established the regulation, is a little risky.

The scope of the relocation mechanism targets seekers whose asylum recognition rate is over 75% - mainly Syrians and Eritreans, according to Eurostat figures. It aims to relieve the States in crisis. The following has been adopted: the first decision involved 40,000 beneficiaries, 60% of whom i.e. 24,000 asylum seekers from Italy and 40% i.e. 16,000 from Greece. The second decision, which was more important, since it involved 120,000 people, initially planned to add Hungary to these two Member States, relieving it of a significant 54,000 people. Since it refused to be considered as a front-line State, Hungary was not included in the calculation, which established 15,600 for Italy (13%) and 50,400 for Hungary (45%) in the 2015/1601 decision - with the remainder being available "to other Member States" [8] until September 2016.

This "fair distribution", which was grudgingly agreed was made official in the final annexes, whose sad figures hardly deserve comment, based on a logic of equations: 40% for the size of the population and the GDP, 10% for the unemployment rate and the average number of asylum requests ongoing over the last four years, with caps of 30% regarding the latter two, in order to prevent threshold effects. On the base of criteria that were already used in July to assess the Member States' reception capacity, the distribution decided in September seriously impacts the situation in some States - like Spain and Portugal for example.

However this plan calls for several remarks.

The first involves the extreme circumspection - to put it mildly - expressed against the Member States benefiting from relocation. The mechanism quite clearly intends to force them to be effective in terms of the exchange of responsibility. Locked into the respect of set deadlines, they are being offered "operational support" together with "additional measures", of a structural nature, comprising a "roadmap", which if not respected could lead to a suspension of the mechanism. From an operational point of view, and notably regarding the "hot spots" spoken of by all, the impact of its introduction on the sovereign decisions of the States being targeted is significant, of which the Italians now seem to be aware.

The asylum seekers are then the target of the greatest mistrust, since there is no guarantee that they will agree to their unilateral placement. The weak point in the European asylum policy, the fear of "secondary movements" of those asylum seekers who have reached the EU, is at the top of everyone's mind. Dublin and Calais prove this: it is extremely difficult to rein in the will of asylum seekers who want to reach Member States where, rightly or wrongly, they believe that they will be able to start life afresh, i.e. in Sweden, Germany and to a lesser degree the UK. Hence there is a series of preventive measures: information stating that in the event of ulterior illegal movement they can in principle only benefit from the rights attached to international protection granted to them in the Member State where they have been relocated, the obligation to present themselves to the authorities, exclusion of any financial encouragement in preference to physical material aid.

A final curiosity lies in the appearance of a rather surprising "temporary solidarity clause" that allows a State "in exceptional circumstances" to exonerate itself to a total of 30% of its solidarity obligation. If it provides justification in line with the Union's values proclaimed in article 2 of the TEU it can notify the Commission that it is temporarily unable to take part in re-locating candidates for a period of one year - and the Council decides on this.

2. The quest for efficacy: a pending issue

In spite of the publication of the texts, the whole legislative mechanism undertaken by the Luxembourg Presidency and Jean-Claude Juncker is running up against the reality of the situation [9].

Firstly its adoption caused a huge political crisis in the Union. The hard core of reticent States, comprising Hungary, Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia, which refused to give in to the pressure of a majority of Members, forced the Council to take a qualified majority vote, with Finland abstaining. Since this break in ordinary consensus prevailed over the word of the Treaties, although it has the merit of providing political clarity, augurs for future crises.

This is firstly because the fate of the migrants, which these minority States will be forced to receive, is obviously a problem in itself. Then there is the material situation of certain States in the face of the crisis, like Hungary, which was initially a beneficiary of the mechanism, remains extremely worrying. And finally it is difficult to hide the fact that the agreement achieved was done so on the one hand, because it was no longer obligatory, and on the other, because of the mobilisation of some States, which are Schengen members, but not of the Union. Since Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Ireland, accepted the reception of some asylum seekers, this enabled certain reticent countries to present the decision achieved to their public opinion as a withdrawal from the estimates.

Secondly, relocation has indeed taken place, and now it is difficult to foresee any back-peddling, without pre-empting the trend that has been set. The institutions' slowness in terms of procedures, the trench warfare between the chancelleries, as well as the technocratic management of decision making, is striking in view of what is immediately at stake. At the same time the first decision applies to people who arrived in Italy and Greece as of 24th March 2015 and the second to those who came as of 15th August 2015. What happens to the other asylum seekers who came from the same place previously?

Consequently we understand why the informal European Council meeting of 23rd September focused - in an appeased atmosphere - on the operational and financial measures designed to strengthen the policy to monitor the borders and aid to the neighbourhood. The call by the heads of State and government to "respect, apply and implement our existing rules, including the Dublin regulation & l'acquis de Schengen" might therefore seem to mean "everything changes so that it all stays the same."

But maybe this will not be the case since the speech delivered by Angela Merkel to the European Parliament on 7th October 2015 alongside François Hollande, which was remarkable from all points of view, might mark a turning point. With the courage that matches her political sense of responsibility the Chancellor is adamant. Refusing to "give in to the temptation of regressing, of acting on a national scale," she suggests that the Union rise to the challenge "of assuming what is attractive about Europe," but on one condition and that is of accepting change, of relinquishing national egotism.

Amongst these signs of egotism the Dublin System, which makes the States suffering migratory pressure bear most of the burden, clearly comes under fire and the German Chancellor made a direct hit: "let's be honest, the Dublin Process, as it stands, is obsolete," she declared to MEPs. The change in paradigm is now possible, opening the way for thought about other solutions including the "fair" distribution of burdens as provided for in the treaties.

If this does not happen, in spite of the inflexion given by the President of the Commission and the Union's most powerful leader, the common asylum policy may very likely bring "a bitter crop", for a long time to come.

[1] : COM (2015) 240

[2] : Right now it is impossible to get the exact overall figure of refugees living in the Union in 2014 from Eurostat.

[3] : France reveals the issues at stake in the present crisis: France has slightly more than 66 million inhabitants around 4 million of whom are foreigners. Amongst these 200,000 people benefited from international protection in 2014 according to OFPRA. The decisions taken in September would lead to an additional 30,000 over two years.

[4] : Apart from French constitutional protection in paragraph 4 of the Preamble of the 1946 Constitution, the German Constitution (art.16a) and if we restrict ourselves just the recalcitrant States, the Hungarian (para 14), Polish (para 56) and Slovakian constitutional (para.53) texts do the same.

[5] : COM (2015) 450

[6] : COM (2015) 286

[7] : COM (2015) 451

[8] : Is Hungary redeeming itself or is it Germany?

[9] : (EU) Council decision 2015/1523 of 14th September 2015 establishing these temporary measures in terms of international protection for Italy and Greece, JOUE L 239.146 15th September 2015 ; (EU) Council decision 2015/1601 22nd September 2015 establishing temporary measures in terms of international protection for Italy and Greece, JOUE L 248.80 24th September 2015.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :