supplement

Sébastien Richard

-

Available versions :

EN

Sébastien Richard

Deemed to be one of the euro zone's "star pupils" at the beginning of the 2000's Ireland (the Celtic Tiger) succeeded in establishing an economic model that was notably built on the attractiveness of its territory, designed to be a doorway to Europe for American multinationals. This undeniable success led to the subsequent development of the country enabling it to break with the image of being the EU's poor cousin. The economic and financial crisis in 2008 highlighted however the faults in this strategy which led Ireland into a liquidities crisis.

1. Review of the Irish Crisis

The origins of the crisis

Driven along by exports and foreign direct investments, which were themselves fostered by an advantageous tax regime, Ireland like Spain appeared for a long time, to be an economic success story in the European Union.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

The continuous reduction of its corporate tax rate has evidently been one of the keys to analysing the country's success. Initially set at 20% in the 1990's, it was brought down to 16% in 2002 and then to 12.5% the following year. The reduced tax rate on profits for export businesses set at 10% has also favoured the establishment of foreign businesses in Ireland. 240,000 Irish citizens, i.e. nearly 5% of the working population, are employed by foreign, mainly American companies, (Apple, eBay, Google, Intel, Microsoft or Twitter). Indeed the USA is the leading foreign investor in Ireland, with 80% of direct investments, owning 51% of the 1004 foreign companies and providing 73% of direct employment. The presence of these companies also leads to indirect employment: 20% of jobs in Ireland are linked to these companies. Until recently Ireland, mainly an agricultural country, became in just a decade, the privileged destination for major service sector companies. In view of the organisation of a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty after the failure of the first held in June 2008, Ireland achieved the guarantee of this specific tax feature, as it did regarding its position on the right to life or its military neutrality, during the European Council in Brussels on 18th and 19th June 2009.

European aid has also been significant in the country's economic development. Between 1973 - the year it joined the EU and 1999 Ireland received funds equal to five times its contribution to the European budget. One third of these transfers were channelled into education and professional training.

The local banking sector supported this development. Three retail banks (the Anglo Irish Bank, the Allied Irish Bank and the Bank of Ireland) and two building societies split the main share of the domestic market of 4.4 million citizens between them until 2010. In this context the fruits of Irish growth were, as in Spain, re-invested in the real estate sector. This choice was made for several reasons and not just economic ones. A euro zone member, Ireland naturally benefited from low interest rates, which were below inflation. With the support of the State, banks were encouraged to invest in real estate, notably in commercial property. But, after decades of poverty, access to property also was also an ideal for a population.

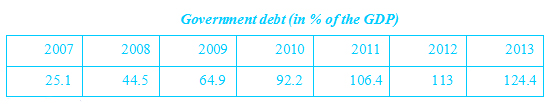

The turbulence in the world's economy revealed over-investment by financial establishments in this sector thereby weakening them. The State was forced to recapitalise and nationalise them at the same time, which blew up its debt and weakened its position on the financial markets. Ireland then faced a liquidities crisis.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

International Aid

In order to resolve the crisis Dublin was granted financial aid in the shape of loans by the European Union, the IMF, Denmark, the UK and Sweden in November 2010 to a total of 67.5 billion €. International financial assistance was provided in equal parts by the IMF, 22.5 billion €; the same sum was granted by the European Union's Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM). This was topped up by loans taken out on the markets by the European Commission.

Euro zone members, via the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), together with the UK (3.8 billion €), Sweden (600 million €) and Denmark (400 million €) contributed to the third part of the aid programme. This assistance was conditioned by the pursuit of three goals:

- the recapitalisation of the banking establishments: the international creditors counted on refinancing of 10 billion € and the introduction of a reserve fund of 25 billion €. A payment of 17.5 billion € taken from the Irish National Pension Reserve Fund helped to achieve this goal;

- the return to a budgetary deficit below 3% by 2015;

- the recovery of growth.

International aid was divided into tranches, each of them being granted according to an estimation of the worked invested by the troika - a mission of experts bringing together representatives of the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF.

Until the euro zone summit on 21st July 2011 the interest rates on the loans granted to Ireland by the EFSM and the EFSF equalled the rates of loans subscribed to by the creditors on the markets, increased by 200 base points for the first three years, and by 300 base points after that. In order to lighten the financial burden weighing on Ireland and also Portugal and to fulfil the plans drawn up in these countries that were to reduce their government debt and deficit, interest rates were cut. These now matched those planned for in the Balance of Payments Facility (BPF launched in October 2009) i.e. around 3.5%. In April 2013 in order to be able to meet payment deadlines Ireland achieved the extension of the duration of the loans granted, by an average 7 years. Average maturity of loans granted by the EFSF lay at 20.8 years. The IMF loans' rate was close to 5% - in the end only 19.5 billion € were in fact paid out.

2. What is the strategy to exit the crisis?

Budgetary consolidation and investment aid to help growth

In order to meet the financial goals provided for in the aid plan and at the same time revive the country's economic activity, the Irish authorities implemented a policy that combined continuing work towards budgetary consolidation that was started in 2008, together with aid for investment and export.

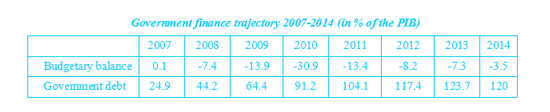

The control of public accounts has been a priority for the government since 2008, the year in which the budgetary balance fell into the negative to total of 7.4% of the GDP. The Fine Gael coalition (centre right)-Labour Party (left) in office since March 2011 continued the work started by the previous government in this respect. From 2008 to 2013 the effort made towards budgetary adjustment totalled 30 billion € i.e. 18.5% of the Irish GDP. Two-thirds of this sum were gained from raising taxes. The introduction of a property tax in July 2013 is symbolic of this. We cannot neglect either the hike in taxes on car registration, alcohols, tobacco, the imposition of a carbon tax on solid fuels or the taxation of maternity leave benefits. In 2013 alone fiscal pressure increased by 1,000 € per household. A tax on water, which has been free to date, is due to be introduced in 2015.

The reduction of public spending firstly involved the civil service. The Croke Park agreement signed with social partners in June 2010 and its addendum implemented in 2013 notably helped achieve the goal set in 2008 to reduce the number of civil servants and thereby the wage bill. This was reduced by 17.7% from 2009 to 2013, decreasing from 17.5 billion to 14.4 billion €. The government now hopes to bring this figure down to 13.7 billion €. Wage cuts varying between 5 and 10% and the freezing of promotions should enable the achievement of this goal. Staffing numbers were also brought down from 320,000 in 2008 to 280,000 in 2013. The increase in working hours from 35 to 37 or from 37 to 39 depending on the sector of activity, the suppression of jobs (healthcare, education and fiscal services) and the redeployment of agents have been the corollary of this policy. Social spending has also been drawn into budgetary consolidation, ranging from means testing for free medical aid, the reduction of the duration of unemployment benefit payments, to cuts in subsidies to pay electricity and telephone bills.

The emphasis placed on the control of public accounts must not obscure targeted action towards export oriented sectors ranging from agriculture to the agro-food industry and aviation. SMEs (99.5% of local businesses and 69% of jobs) have also benefited from tax exemptions if they supported innovation or investment abroad. In May 2014 the government also announced the launch of a Strategic Investment Fund endowed with a budget of 20 billion €. Using the National Pension Fund it is designed to finance national projects in view of reviving growth and employment. Priority targets of this new tool involve infrastructures, capital-risk, innovation and new technologies.

Evident results

The growth expected at the end of 2014, 4.5% of the GDP, whilst initial estimates forecast on 2.1%, is proof of the success of this policy. Although the country's activity has been maintained over the last few years by exports, household demand is now helping growth, via capital goods and construction (60,000 cars were sold in 2013). This development is one of note since consumption plummeted by 26% between 2008 and 2013.

Source : Gouvernement irlandais

Source : Gouvernement irlandais

The recovery of growth coupled with a rise in tax revenues should help Ireland meet the budgetary goals set by the troika quite easily. The budgetary deficit might lie at 3.5% of the GDP, i.e. a rate below the initial target of 4.8%. The trajectory defined has been respected since the start of the aid programme. The government's ambition in 2015 is to achieve deficit below 3% of the GDP. Debt remains high however at 123.7% of the GDP at the end of 2013. It might be brought down to 120% at the end of the year.

Source : Eurostat

Source : Eurostat

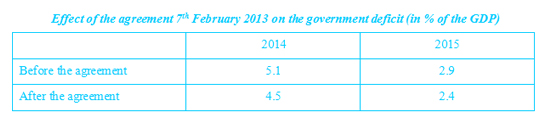

The bank crisis was partly resolved in February 2013. The Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC) was created in July 2011 merging the Anglo Irish Bank (AIB) and the Irish Nationwide Building Society (INBS), both close to bankruptcy after the collapse of the Irish real estate bubble. These two establishments were nationalised in 2009 and 2010. To prevent the collapse of these two banks the government granted emergency aid totalling 31 billion € in the shape of promissory notes. This sum was designed to help them refinance with the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) and therefore with the European Central Bank (ECB). In no way were these promissory notes an acknowledgement of debt on the part of the Irish State: from now to 2031 the Irish government has committed to reimbursing every 31st March 3.1 billion € to the IRBC. This sum represents 2% of the Irish GDP. The promissory notes were used as "collateral" by the IRBC with the CBI, which in exchange provided it with emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). 16 billion € IRBC assets were also paid out to guarantee the emergency liquidities that finally totalled 40 billion €. 6 billion have already been paid back by the Irish authorities. Since it entered office in March 2011 the government coalition had been hoping to postpone the reimbursement of the promissory notes, in order to lighten its financing requirements and to guarantee more soundly its return to the market at the end of 2013. To do this it had to come to an agreement with the CBI and also as part of the European system of European central banks, with the ECB. This agreement came on 7th February 2013. It planned for the transformation of 25 billion € in promissory notes into 25 billion € in State bonds whose maturity varied between 2038 and 2053. The interest rate of these bonds is estimated at 3% whilst the promissory notes totalled 8%. Although this solution has increased the State's debt by 25 billion it does however relieve the State's short term financing requirements and therefore helps the government to respect the budgetary trajectory negotiated with the troika.

Source : Sénat français [1]

Source : Sénat français [1]

Exit from the international aid programme

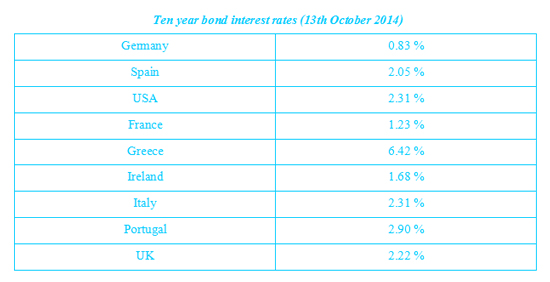

With these results in hand the exit from the financial assistance programme might seem to have been a logical development. In July 2012 it was preceded by a return to the financial markets since Ireland had been excluded from them since September 2010. Three month, five and eight year maturities highlighted the rise in confidence regarding Irish securities. A ten year maturity in March 2013 was a test, the premium reached 4.15%. Ten year bonds were being traded on the secondary market at rates of 14% in July 2011. At the end of the day 10.5 billion € were raised on the bond markets in 2013 before the exit of the aid programme. The Irish authorities were therefore able to put together reserves totalling 20 billion € which are designed to enable the country to fulfil its financial commitments by 2015.

Deemed to be a major step in view the country's financial recovery on the part of the Irish government the end of the aid programme was formally confirmed on 15th December 2013. The troika is due however to undertake six-monthly monitoring missions until Ireland has reimbursed 75% of the aid granted. This is due in 2031.

Moreover Ireland did not want to use a preventive line of credit from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The granting of this was indeed conditioned by the introduction of a budgetary stability programme defined by the European Commission. As a result Ireland is not eligible to the ECB's OMT (Outright Monetary Transactions) programme (whereby the ECB purchases sovereign debt bonds), reserved for countries receiving financial assistance.

Behind Ireland's refusal of further assistance is the authorities desire to send out a positive signal to the financial markets. This strategy is proving justified for the time being. Just a few weeks after exiting the aid programme on 8th January 2014 Ireland had in effect issued 3.75 billion € in 10 year maturities at a rate of 3.543%. This deadline has been qualified as the "debt wall" by financial analysts. The good performance by Irish securities can also be found on the secondary market where the yield of 10 year bonds is at historically low levels. Interest rates on Irish bonds are notably lower than those targeting British or American papers.

Source : Euronext

Source : Euronext

At the same time Ireland's sovereign credit rating was raised on 6th June last by Standard & Poor's. Its counterpart Fitch did the same on 16th August 2014. Initially established at BBB+ with both agencies (Average inferior quality), the rating rose to A- (Average superior quality), with Standard & Poor's adding a positive outlook.

Dublin is due to have invested between 6 and 10 billion € in securities on the bond markets in 2014.

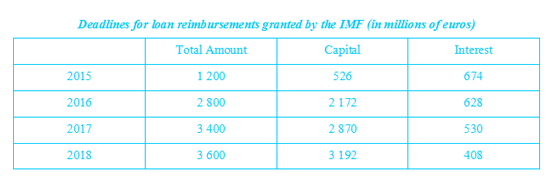

The exit plan is due to continue over the next few weeks with an early reimbursement of IMF loans. This was supported by the ECOFIN Council dated 12th September. Early reimbursement might enable Ireland savings of 375 million € per year in terms of interest payments.

Source : IMF

Source : IMF

In spite of this apparently successful exit it is impossible however to ignore recurring criticism by the Irish authorities regarding the structure of the aid plan and notably the management of the bank debt, which has been the responsibility of the State since the nationalisations of 2010. As part of Banking Union, which is due to be introduced in November 2014, the European Financial Stability Mechanism (ESM) can now recapitalise struggling bank establishments directly. 60 billion € of the 500 available to the ESM should be available to this effect. It is in fact about not increasing the debt of the State in which the bank involved is established. It remains that this possibility is only to be used to address future crises and not pre-existing ones which of course irritates Dublin. The Irish government would have liked the recapitalisation of three establishments a posteriori (Allied Irish Bank, Bank of Ireland et Permanent TSB) to a total of 28 billion €, i.e. the sum paid by the State for their rescue in 2010.

3. Challenges still to be overcome

However two factors nuance this overly optimistic view of the country's economic situation, whether we consider unemployment and more particularly youth unemployment, and private and corporate debt.

Youth unemployment

Unemployment is the main challenge to the country that has started to recover growth however. We should recall that the unemployment rate tripled between 2007 and 2011, affecting 15.1% of the working population. The multiplication of action plans in this area (Job Initiative, Action Plan for Jobs, Pathway to Work), combining tax incentives - corporate tax exemption for new businesses, social contribution relief - and the creation of structures designed to supports SMEs on the local and also international market, such as the rationalisation of the public employment service, led to a reduction of the rate to 11.7% at the beginning of 2014. 61,000 jobs were created in 2013. The government is now counting on the continued decline in unemployment observed since July 2012 and has set the goal of 10.5% in 2015. The European Commission also shares this goal and is counting on an unemployment rate of 4% by 2025. To support it there is the quality of local training, with 80% of the unemployed being qualified, which should facilitate finding a job. However it remains that youth unemployment is still at a worrying level of 24% of the 20-24 year olds. The unemployment rate of young people under 30 now totals 30%. This problem is most often settled by emigration: 70% of the 87,000 annual migrants are aged 20 to 30, 62% of them have higher education diplomas. Youth unemployment has to be a priority for Ireland's government which is working on two levers:

- The reduction of benefits paid to young unemployed people aged 20 to 25. The aim is to encourage those affected to follow training or to change professions. State financing is oriented towards a dedicated youth investment fund which has a budget of 14 billion € and the creation of 300 000 places in training and education programmes (cost estimated at 1.6 billion €);

- The use of dedicated EU funds for youth employment (Initiative for Youth Employment) launched in June 2013 with a budget of 10 billion €. Ireland has an envelope of 68 million €. This sum should help towards financing existing programmes like the national Pathways to Work action plan and also additional measures: Tús programmes for temporary employment or JobBridge for Disadvantaged Youth, focused on internships. Notably the Youth Guarantee Mechanism put forward by the Irish government is to be used. Within two years this measure is due to provide training for the under 18's or help their reintegration into school system. Tested on 600 young people the Ballymun project enabled 75% of them to find work (40%) or training (60%).

Private debt

The other major issue concerns the financing of the real economy whilst the real estate crisis still weighs over the activity of the financial establishments. Household debt represents 108% of the Irish GDP, 87% of these debts involve mortgage loans. The number of loans in arears in excess of 80 days represents around 100,000 loans amid the 760,000 granted by the banks. One household in eight is affected by late payments, 27% of loans holders are in a precarious situation. The value of mortgaged property is still a risk in view of the collapse of prices in the sector. This fall in price, moderated by the recovery seen in Dublin, is notably worsened by the vacancy of 290,000 lodgings across the country, i.e. 14.5% of housing stocks. Half of the loans granted to SMEs (58 billion €) to finance their real estate projects are also deemed as bad debts.

Given this challenge the financial establishments, under the Central Bank of Ireland's guidance, are progressively introducing procedures to recover this debt which was not possible in the past. The granting of loans is now considered differently: indeed until the start of the crisis loans were calculated according to the value of the property and not on the ability of the borrowers to pay. The Central Bank of Ireland now obliges establishments to offer rescheduling solutions to their clients in difficulty, households and businesses alike. 85% of households should be able to have a new financing plan by the end of 2014.

It is in this context that we should analyse the decline of outstanding loans granted overall in 2013 after two years of stagnation. 57% of loans requests made by SMEs were rejected. Generally the State, business and household accumulated debt represents 489% of the GDP in 2014 against 272% before the crisis. As a result Ireland is the country with the most debt in the world.

To these two economic factors we might add that public opinion is somewhat weary after seven years of austerity, highlighted by the European elections on 25th May 2014. The Labour Party, a member of the government coalition, emerged weakened after the election. A slowing in work towards budgetary consolidation in 2015 is now on the agenda. The aim seems to be to support the recovery of domestic demand from now on. A reduction in the marginal income tax rate is being planned.

The unknown fiscal factor

Although it was not addressed during the November 2010 negotiations on the conditions for the granting of international aid between the EU, the IMF and Ireland, the issue of corporate tax might also prove to be a problem for the Irish government. Although there is a political consensus on the issue of the rate, many questions remain about the effective payment of this tax by the multinationals. An investigative committee at the American Congress highlighted in 2013 that the tax rate paid by Apple was closer to 2.2% than the official 12.5%. Firstly the Irish government indicated that the effective rate that multinational companies were subject to varied between 10.7% and 10.9%. This difference was said to have been made possible due to the so-called hybrid nature of these large companies and the possibility offered to them of benefiting from the "double Irish" principle. Provided for in Irish fiscal law it enables foreign businesses to domicile themselves legally in Ireland and yet benefit from tax domicile outside of the country where they declare all or some of their profits. By using this possibility Google is registered from a tax point of view in Bermuda and Apple was exempted from corporate tax from 2004 to 2008. Agreements between the latter and the Irish authorities on the means of calculating the tax base of its branches also affected the real taxation of the company. This issue is significant at a time when the government is trying to continue with its budgetary austerity programme without weighing too much on households. The figures speak for themselves: although in view of Irish statistics the profits made by American businesses established in Ireland totalled 40 billion $ in 2011, in reality they totalled 147 billion $ according to the American authorities. Apple Sales Ireland registered profit of 16.6 billion € in 2011, with its tax based being limited however to a sum between 50 and 60 million €. As a result of this the Irish authorities now want to revise fiscal legislation as part of the finance bill in 2015, as put forward on 14th October last. The hybrid status granted to multinational companies has now been done away with, thereby preventing the use of the "double Irish" principle. Although internal political reasons govern a modification like this we should not neglect the influence of the OECD and the EU in raising the government's awareness of the problem. Hence on 30th September 2014 the European Commission asked the Irish authorities to communicate within the next month detailed explanations of the agreements made with Apple in 1991 and in 2007. In the European Commission's opinion these agreements might be assimilated to State aid. This step is part of the Commission's inquiry launched on 11th June 2014. Now we shall have to see whether the attractiveness of Ireland, a vital element in the country's growth, will be as strong if the present legislation is revised.

Conclusion

The work undertaken by Ireland, notably in terms of the budget, has been rewarded over the last few weeks by a strengthened position on the financial markets and a return to growth. The financial assistance programme which it has benefited from and cooperation work undertaken with the troika can, in this regard, be deemed a success. It might seem to be a path to follow on the part of countries still under assistance, like Greece or Cyprus, and even Portugal, which although it officially exited the financial assistance programme on 17th May 2014, is still encountering some difficulties. Slowing in budgetary consolidation work announced by the Irish government for next year cannot for the time being be interpreted as a sign of a final return to normal. Ireland still faces relatively high unemployment, the financing of its economy is still being weakened by the fallout of the real estate crisis and the weight of its debt is colossal. Ireland, which is an open economy, dependent on foreign investors, is also sensitive to the hazards of the international situation, and particularly American and British financing. In this context we shall have to pay special attention over the next few weeks to the effects of the reform that will affect the tax domicile of multinational companies and also a possible exit by the UK, its leading trade partner, from the European Union.

[1] Le réveil du Tigre celtique ? L'Irlande et les pays sous assistance financière, report by Jean-François Humbert on behalf of the European Affairs Committee at the French Senate (n°603 2013-2014)

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :