Democracy and citizenship

Julien Zalc,

Julien Zalc

-

Available versions :

EN

Julien Zalc

Julien Zalc

Introduction

From 22nd to 25th May 2014 Europeans will again be called to ballot to elect their representatives in the European Parliament. Beyond the new political configuration that will result from this vote the abstention rate will be one of the main issues in these elections: indeed since the first European elections in 1979 turnout has constantly declined, dropping from 62% to 43% in 2009.

Even if it is risky, just one year before the vote, to make any forecast about the 2014 election turnout, recent developments across several EU support indexes tend towards a pessimistic outcome: indeed European opinion about the Union has never been so low.

And the least we can say is that the elections held on 14th April in Croatia (when the Croats elected 12 MEPs to represent them in Parliament as they enter the Union on July 1st 2013) were not very encouraging: only 20.79% of the Croats voted. In 2009 only Slovakia did worse, achieving a turnout of 19.64%!

How can we explain this sharp downturn in attitude towards Europe? Is it a direct result of the economic quagmire in which Europe has been wallowing since the start of the crisis? Are other factors responsible? Is the European Union's image suffering because of a rising trend amongst European public opinion to withdraw? This analysis will try to answer some of these questions by using data from the Eurobarometer which enable the precise study of developments in feelings about the Union over time.

Firstly, it seems appropriate to review euroscepticism: this term defines a trend that has existed since the beginning of European integration, marked by a desire for national refocusing and Member States' determination to protect their sovereignty. Eurosceptics can adhere to extremely different political trends, both on the left (Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France, for example) and the right of the political scale (Marine Le Pen in France or Geert Wilders in the Netherlands). In this article euroscepticism is used in the widest sense of the term, to define the negative opinion regarding the Union (negative image, mistrust, pessimism about the future of Europe). Is the declining image of the Europe a reality? When did it start? Is the downturn equal throughout? Are some countries/categories of Europeans affected more than others? The reasons explaining this rise in euroscepticism will be analysed starting with the economic factor. "Is is just a question of 'the economy stupid'?" Or are other factors, notably a trend towards national withdrawal contributing towards a decline in confidence in the Union? Finally the reasons for hope for the European Union and the identification of some levers that might reverse the trend will also be set out.

1. EUROSCEPTICISM RISING SHARPLY SINCE 2007

The Union is suffering a real image deficit in the eyes of European public opinion. Three indexes are analysed in this case: the European Union's image, confidence, optimism for its future. As of 2007 the downward trend of each of these has been constant and this in spite of some very often anecdotal improvements.

In the spring of 2007 [1], more than one European in two said they thought positively about the European Union (52%), which illustrated a rise since 2004. In the autumn of 2012 [2], less than a third declared this, i.e. a fall of over 20 percentage points. At the same the share of Europeans with a negative image of the Union had more than doubled, rising from 15% to 29%.

Confidence in the European Union follows exactly the same trend: after having reached a peak in the spring of 2007 (57%) it has been declining on a regular basis. Mistrust became predominant in the spring of 2010 [3], and in the most recent survey in autumn 2012 only one third of Europeans said they trusted in the European Union (33%). The confidence index (difference between confidence and mistrust) plummeted from +25 in the spring of 2007 to -24 in the autumn of 2012!

The question regarding optimism about the future of the European Union has only been asked since spring of 2007. But the trend is the same: the share of optimists dropped from 69% in the spring of 2007 to 50% in the autumn 2012 survey. And although there remains a majority, a strong minority of Europeans now say they are now pessimistic about the EU's future (45%).

In the countries in which erosion of support to the European Union has been the most dramatic, a national analysis of results shows that this downturn in confidence and the image of the European Union since 2007 has not been homogeneous: although the three indexes studied have worsened since the spring of 2007 in all of the EU countries, except for one [4], some Member States have been affected more than others, notably in the countries in the south of Europe [5]. The Union's image has suffered particularly in Spain (-41 points in total positive opinions), in Greece (-33) and in Portugal (-33); this also applies to confidence (Greece, -45; Spain, -35; Portugal, -31; and Cyprus, -30), and optimism in the future (Greece, -40; Cyprus, -34; Portugal, -39; and Spain, -26).

Although the decline appears in all countries - how have these indexes developed within he various categories of Europeans? The same observation applies: whichever indicator is studied the decline is massive in all socio-demographic categories. It is all the more worrying that this decline is worse amongst the categories which are usually europhile: young workers, executives and the more qualified (cf. see the table below).

To a certain degree it is logical for the decline to be greater amongst these categories because indicators were highest within these segments of the population in the spring of 2007 (62% positive image amongst the 15-24 year olds, the more qualified and executives, against 57% amongst all Europeans). This is still of great concern however: the European Union no longer seems to enjoy the opinion multipliers who would be likely to defend and promote it within public opinion.

2. THE ECONOMIC CRISIS, THE MAIN EXPLANATORY FACTOR?

And so what is behind this tailspin? Obviously the economic factor immediately springs to mind: the perception of the national economic situation indeed reached lowest ebb in the Eurobarometer survey undertaken at the beginning of 2009 [6], some months after the start of the crisis and this has only improved tentatively since. Since the autumn 2008 survey [7], more than two thirds of Europeans have come to believe that their country's economic situation is bad. And these results would be even worse if the extremely good results achieved by Germany since the autumn of 2010 (with more than six Germans in ten deeming the economic situation of their country good) were not there to improve the European average (German results contribute to more than 15% of the European average, weighted according to the Member States' respective populations).

One thing is certain however: the three support indicators to the European Union are running alongside the perception the Europeans have of their national economic situation: since the spring of 2007 we can see positive correlations of +0.42 in terms of the European Union's image, +0.43 in terms of confidence and +0.46 in terms of optimism in the future of Europe.

We might settle with that and conclude that if Europeans are turning away from the European Union it is a direct consequence of the economic situation. However a country-by-country analysis relativises this argument.

The graph below in which the positions of the various Member States is plotted according to their perception of the national economic situations (in abscissa) and the confidence in their national government (in ordinate), confirms that there is a strong link between these two variables (a positive correlation of 0.87). The countries with a healthy economy attribute their good results to their government (Sweden and Luxembourg) and conversely mistrust of the government is particularly strong in Member States where the economic situation is disastrous (Spain and Greece).

But the result is quite different if we analyse the link between the perception of the national economic situation and confidence in the European Union. The following graph illustrates a variety of situations: public opinion in Sweden and Germany is much more satisfied with the national economic situation than the European average but this lies on the same level if not below the average when it comes to expressing their confidence in the Union. Conversely in Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary and even Slovakia confidence in the Union is clearly higher than the European average, in spite of a national economic perception which is quite below the European average. The weak correlation between the two variables (0.17) confirms that the key factors in confidence in the Union are not just economic, and that other elements are at play.

3. THE TEMPTATION TOWARDS NATIONAL WITHDRAWAL: A REASON FOR THE RISE IN MISTRUST OF THE EU?

Regarding how Europeans perceive globalisation, a analysis over time reveals that it has worsened since 2008 and the start of the crisis. In spite of a slight recovery since autumn 2011 [8], the "agree" indicator (difference between the share of "agree" and "do not agree" with the statement "globalisation represents an opportunity for economic growth" has declined by 13 points (from +29 to +16). This decline involves a great majority of the Member States: in 22 countries out of 27, the vision of globalisation as an economic opportunity has lost ground, sometimes in a spectacular manner. This is notably true in Cyprus (-56 points of the "agree" index), Romania (-48), Portugal (-40), in the Czech Republic (-39) and Slovenia (-37).

Moreover we note that the image of globalisation has particularly declined in the categories most exposed to unemployment: young working people (-17 points in the "agree" indicator amongst the 25-39 year olds), workers (-18) and the unemployed (-18). The crisis seems to have damaged the image of globalisation: negative aspects and notably the exposure caused in terms of increased competition with the emerging countries appear more clearly to European citizens. Most Europeans continue however to see it positively.

This is not the case as far as the Union's enlargement to include new countries is concerned. The most recent enlargement took place on January 1st 2007, when the European Union grew from 25 to 27 Member States as Romania and Bulgaria joined. Interviewed just a few months later, in the spring of 2007, nearly half of the Europeans said they supported the future enlargement of Europe towards other countries in the next few years (49% in support, 39% against). Since then this support has continued to decline amongst public opinion and in the autumn of 2012 the trend reversed almost identical proportions: 38% in favour, but 52% were against any further enlargement.

Close up support to enlargement has declined in all EU countries except for one. In Luxembourg the rate has remained constant. Some contractions are spectacular, notably in Cyprus (-63 points of the support index [9]), in the Czech Republic (-50) and in Spain (-41). In some Member States public opinion is more than just turning away from enlargement: it is undergoing a complete turnaround. In seven Member States there has been a move in which opposition to future enlargements is now in the majority. A socio-demographic analysis reveals that support to future enlargements has declined in almost all categories.

Is there a common point in the simultaneous contractions of favourable opinions about globalisation and enlargement? A trend seems to be emerging in European public opinion in terms of tension about openness towards others: in other words people are tempted to withdraw. It is as if many Europeans, as they are hard hit by the crisis, are turning towards a political framework deemed to more protective, i.e. the State and they believe that they will find solutions to the crisis alone.

Furthermore although a majority of them continue to think that it is by taking coordinated steps with other Member States that they will be best protected against the crisis, the share who believe the contrary that salvation is in national solutions has risen from 26% in January , 2009 to 38% in March 2012.

And quite logically the rise of these ideas is not without effect on support to the European Union , as illustrated in the table below.

Those who are sceptical about the positive effects of globalisation on growth as well as those against enlargement are amongst the most critical as far the European Union is concerned. In the crisis a large minority of Europeans seem to feel that it would be easier to go it alone. They are resolutely turning away from the European Union. But will it be forever?

The trend towards national withdrawal is linked to the crisis. And therefore the influence of this phenomenon on the rise of euroscepticism is connected to the economic situation. However it is neither a direct nor immediate consequence of it. The crisis is causing phenomena in opinion such as the trend to national withdrawal, and these are affecting support to the European Union.

4. REASONS FOR HOPE AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Is the outlook so dark? Are the rising trends of national withdrawal and the decline in support indicators to the EU inexorable? In fact there are a certain number of encouraging factors and reasons for hope.

In spite of a growing feeling that national solutions would provide better protection against the crisis, the Union still enjoys some credit amongst the European population, notably in comparison with other major players: hence it is deemed the most able to act effectively to counter the crisis. Although it has shared this lead position once with national government (in the spring of 2012 [10]), and although it was beaten by the G8 when the question was first set (in January 2009, some months only after the start of the crisis [11]), the EU came out ahead of all of the others. The highest number of statements in support of the EU were recorded in Poland (36%), Bulgaria, in Luxembourg and in Malta (31% each).

And although their figures are the ones to have declined the most in terms of support to the Union, young people (27% of the 15-24 year olds), the most qualified (25%) and executives (25%) are still in the majority to think that Europe is best placed to act effectively.

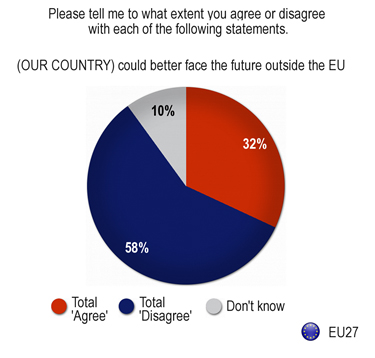

Furthermore with this sharp decline in support to the Union we might legitimately wonder whether Europeans think they would be better off if their country were not an EU member. But this is not the case! On the contrary, nearly six Europeans in ten do not agree that their country would have a better chance in the future if it were not an EU member (58%, a quarter of whom fall within the category "do not agree at all"). Slightly less than one third believe the contrary and think that their country would be better equipped to face the future outside of the EU (32%).

A national analysis almost totally confirms the feeling of a Union, which ultimately, would be protective to a certain extent in the present economic context: in 26 Member States most of those interviewed believe that to face the future it is preferable for the their country to be an EU member. The highest scores are achieved in Denmark (77% do not agree with the suggestion ("(OUR COUNTRY) might be able to face the future better if it were outside of the EU"), in the Netherlands (75%) and in Luxembourg (74%). The only exception to the rule, and unsurprisingly, is the UK where the population mainly believes that the country would do better outside of Europe.

In all categories (sex, age, level of education and socio-professional category), a clear majority of Europeans believe that their country is better equipped to face the future within the EU.

What should Europe do about this? How can it show European citizens that the Union is on their side in the crisis? In this instance action is key. Europeans are expecting the Union to act against the crisis: if we look at the opinion the Europeans have about the efficacy of the action taken by the EU since the start of the crisis we can see a strong correlation with confidence in the EU (0.81, spring 2012 [12]): quite logically attitudes towards Europe are strongly linked to the perceived efficacy of European policies.

The Union must act. But how? Firstly by playing a protective, supportive role to its citizens: indeed it is in the social sphere that the Union is expected to act. More than half of Europeans believe that the fight to counter poverty and social exclusion must the European Parliament's top priority (53%). Far ahead of the coordination of economic, budgetary and fiscal policies (35%), lie policies concerning agriculture that respect the environment and help towards the world's food balance (30%), and the fight to counter climate change (28%). Other aspects are quoted by less than one quarter of those interviewed.

Every time that this question is asked the fight to counter poverty and social exclusion comes out far ahead as the Europeans' top priority. In the first months of the crisis in September 2008 troubles seemed to be far away, a kind of abstract event that involved the world of finance, bankers and traders. But now the crisis is there, it is real. The population is being affected more directly; unemployment has never been as high in the EU and it is by far the most important cause of concern for European citizens. And therefore it is regarding social issues, before all others, that action is expected on the part of the EU.

Conclusion

Since 2007, the rise of euroscepticism seems to be irresistible. Image, confidence, optimism about the future, indicators vary but the observation is constant: increasingly Europeans have less confidence in the EU.

And although the temptation is great to explain this downward trend because of the economic situation it has to be admitted that this is not enough.

More and more Europeans are tempted by national withdrawal. After having believed, in the first few months of the crisis, that the EU might serve as a shield the idea that they might do better alone without the other Member States is gaining ground. Obviously the crisis is notably blamed for the rise in this trend in public opinion. Hence the economic situation is affecting support to the EU - not in a direct, immediate manner but by means of other secondary dimensions. In other words although negative opinions of Europe are rising it is not exclusively because of the poor economic situation. It is also because the economic situation is leading to the formation of other opinions that also affect support to the EU negatively.

In all events the Union is still deemed to be the most adequate player to act effectively against the crisis. But this also means that the Union has a certain responsibility, even a duty: which is to act. Europeans want to see Europe acting to support the growing number of citizens who are being directly affected by the crisis. And it is clearly in terms of countering unemployment and support to the most vulnerable populations that action is mainly expected of the Union. The Union must be seen to be "at work" in the field alongside its citizens. This is how it will succeed in restoring its image that has been seriously damaged since the start of the crisis. Hence it is vital for the Union to be seen to be at work - it must communicate, more and better, about its work to support European citizens.

A year before the next European elections there is still time to inverse or at least change this downward trend: the success of the next European election depends on it, because the danger of seeing a total loss of interest in the next elections is a reality. The explanation that would be given would be "in all events it changes nothing for me". In their 20% turnout the Croats have issued a warning that should be taken seriously. Indeed, we can be sure that the most fervent opponents to the Union will know how to act in this election.

[1] Standard Eurobarometer 67, spring 2007.

[2] Standard Eurobarometer 78, autumn 2012.

[3] Standard Eurobarometer 73, spring 2010.

[4] Bulgaria where confidence has risen slightly since 2007 (+6 points, from 54% to 60% ; but -3 in terms of image and -2 for optimism about the future).

[5] See notably the article by Daniel Debomy, " L'UE non; l'euro oui! Les opinions publiques européennes face à la crise (2007-2012) ", for Notre Europe.

[6] EB71.1 Special Eurobarometer 311, the economic and financial crisis, January-February 2009.

[7] Standard Eurobarometer 70, autumn 2008.

[8] Standard Eurobarometer 76, autumn 2011

[9] Difference between the shares of " for " and " against " any future enlargement to other countries in the next few years..

[10] Standard Eurobarometer EB77

[11] EB71.1 Eurobarometer special 311, the economic and financial crisis, January-February 2009. In the following waves, the G8 was replaced by the G20.

[12] Standard Eurobarometer EB77, spring 2012 [JZA1]Traduit par JZ

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :