Strategy, Security and Defence

Damien Degeorges

-

Available versions :

EN

Damien Degeorges

The Arctic: a new frontier in international relations

The Arctic, which to date has been a region on the periphery of world trade, has now become the new frontier in international relations due to developments in climate change. If the Arctic polar circle (66° North) crosses through a State it is thereby classed as being Arctic. Eight States comprise the Arctic region: Canada, Denmark/Faroe Islands/Greenland, the USA, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia and Sweden. The European Union, a partly supranational entity of which Denmark (an Arctic State because of a non-European territory, Greenland), Finland and Sweden are members, is geographically Arctic.

Three areas comprise the Arctic region: North America; the North of Europe and Russia which is by far the regional superpower, due to the vastness of its Arctic territory and its capabilities (ice-breakers) which are much greater than the other Arctic States. The States on the shores of the Arctic Ocean (Canada, Denmark/Greenland, USA, Norway and Russia) form the core of Arctic governance, whilst the Arctic Council created in 1996, is the forum which rallies all of the region's players (Arctic States, permanent members representing the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, observers). In 2012 the six States which enjoy permanent observer status within the Arctic Council were all members of the European Union (Germany, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Poland and the UK). Whilst polar research lies just out of reach of the non-Arctic States in the region, rising interest in the Arctic has led to an increase in candidates vying for permanent observer status: the main ones being, China and the European Union. A decision on these candidates is due to be given in May 2013 at the end of the Swedish Chairmanship of the Arctic Council.

The impact of climate change has changed international society's view of the Arctic region, because of the issues at stake and the challenges which these changes imply: rising sea levels due to the melting of the Greenland ice-sheet, the opening of new maritime routes due to the summer melting of the Arctic pack ice, easier access to natural off-shore resources in a region where environmental risks remain high, the migration of fishery resources, security issues, and the settlement of territorial disputes, cooperation between regional players (including Russia and the USA), cohabitation between world powers in an area with regional governance etc. Lastly the Arctic does not leave the world of defence indifferent either, particularly the nuclear powers. The Arctic, where nuclear submarines cross paths is indeed a privileged area for the coverage of a wide part of the earth close to the main nuclear powers' home ports. NATO is interested in the Arctic without however becoming more involved in the area. Four Arctic Coastal States lying on the shores of the Arctic Ocean are NATO members (USA, Canada, Denmark and Norway). However a higher profile for NATO in this region was not on the agenda in 2012.

Although greater cooperation between Russia and the other Arctic States is still a major stake for future developments in the region, the consideration of rapid change in Greenland, an autonomous Danish territory, is vital and must not be underestimated; default on the part of an independent Greenland's economy would have major consequences on developments in the Arctic and the world's energy security.

Asia's growing interest in the Arctic – China, South Korea, Japan, India, Singapore etc... illustrates the importance of this region for the world and provides the Nordic countries with a greater role – they are small in comparison with the G8 Arctic powers but do benefit from having a strategic Arctic "position". This is a major asset in terms of these States relations with major Asian powers such as China.

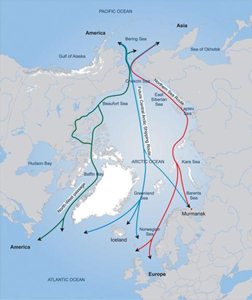

By simply linking up the world's major economic blocks – Asia, Europe and America – the Arctic distinguishes itself as a globalised region. By cutting nearly half of the distance between Asia and Europe in two (by around 40%), the Arctic will accelerate globalisation. Furthermore the fact that powers like China and India are interested in the Arctic, to point of asking for permanent observer status within the Arctic Council, shows that the Arctic will be a key region in the 21st century.

Maritime routes planned in the Arctic.

Maritime routes planned in the Arctic.

Source : NATO Parliamentary Assembly, http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=2082

The European Union: a misinterpreted player in the Arctic.

As early as 2002, well before the present interest for the Arctic region, the European Union revealed its Arctic aspect, under the impetus of the Danish Presidency of the Council of the European Union and the Greenland (not an EU member however), by introducing the idea of an "Arctic window" in the European Union's Northern Dimension.

The European Union, an entity that is considered by some as an external player in the region, is geographically Arctic. A lack of confidence and assertion on the issue is seen regularly in the speeches delivered by the European institutions' representatives. The European Union, which is the primary fund provider for polar research in the Arctic, is also responsible via the transfer of competence between Member States of areas that are directly linked to the Arctic. Moreover the European Union legislates on issues that affect other Arctic States directly, such as Iceland, Norway, which are members of the European Economic Area (EEA). Decisions such as the ban on importing seal products, in spite of an exemption clause for products emanating from traditional Inuit hunting communities, or the European Parliament's former wish to see the launch of negotiations in view of adopting an international treaty relative to the protection of the Arctic, did not help the European bid for permanent observer status within the Arctic Council. However the fact that all of the permanent observers were EU members in 2012 can but legitimise the European Commission's bid to integrate the Arctic Council as a permanent observer. This is all truer if we consider that six permanent observer States have integrated the Arctic Council mainly by their involvement in polar research, an area in which the European Union has more than proved itself.

Greenland has been the venue for reflection on Europe's Arctic policy: the autonomous territory hosted a conference of the Swedish Presidency of the Nordic Council of Ministers in 2008 in which representatives of the European institutions took part. In 2012 the European Commission and the EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Arctic Communication [1] recalled the importance of an enhanced relationship between Greenland and the European Union.

Amongst the EU Members, and particularly amongst the Nordic States, the approach to the Arctic is above all national. Denmark is by far the most influential of the European Union's countries in the Arctic, since it is one of the five Arctic Coastal States on the shores of the Arctic Ocean and because of this, a member of the "first circle". However Denmark was the last Arctic State to publish its Arctic Strategy in 2011. Sweden, which holds the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council until 2013 is still a rather "neutral" player in the Arctic political game, privileging more consensual issues such as the environment. Finland is trying to distinguish itself as the European Union's Arctic asset, on the border between Europe and Russia. Amongst the permanent observers within the Arctic Council, Germany and the UK are by far the most active in terms of strategic research on the Arctic. Thought on an Arctic strategy for non-Arctic countries was still impossible just a few years ago: countries like Germany and France have however started considering this in order to assert their interest in the Arctic region.

Greenland and the European Union: the stakes of a deeper relationship

The development of Greenland's status has been linked to European integration since internal autonomy in 1979. In 1972 Greenland, which was then a Danish 'county' voted against joining the Common Market, but Denmark and Greenland's votes together supported entry into the European Economic Community, and so Greenland integrated the European entity in 1973, but against its will. The economic impact of this membership helped Greenland achieve internal autonomy within the Kingdom of Denmark in 1979. A referendum then confirmed that most of Greenland's population did not want to be part of European integration. Greenland exited the Common Market in 1985 and in 2012 was the only territory to have left the European Union. The launch of Greenland's enhanced autonomy (Self Rule) in 2009, the last stage before independence, was initiated by a government coalition agreement in 1999 between Greenland's leftwing parties Siumut and Inuit Ataqatigiit, which was to lead to an assessment of the institutional framework of autonomy. Greenland deemed that a greater transfer of competence by Denmark over to the EU had had an increasing effect on the relations defined as part of the agreement between Greenland and the European Union.

Some believe that Greenland's shortest path to independence would be via re-joining a partially supranational entity like the European Union. Others do not believe in this perspective, privileging an enhanced partnership. Iceland's candidacy to the European Union has re-initiated debate over the EU in Greenland. A recent, rapid development in the position of Greenland's head of government Kuupik Kleist, concerning relations between the EU and Greenland should be noted. When interviewed by the Danish daily, Politiken in 2012 Kuupik Kleist declared that "it was silly for Denmark not to be part of the euro" [2]. Greenland is one of the most strategic Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) for the European Union. This status notably provides it with access to European programmes in the area of education, a key sector for the territory's future and a strategic tool for the EU, since the training of Greenland's future elite would offer privileged access to this territory which aims to become independent.

Greenland, which is four times the size of France (around half of the European Union), is inhabited by around 57,000 inhabitants, has everything to attract the major powers, both from an energy point of view, with a considerable potential in natural resources (hydrocarbons, minerals, water) as well as in terms of the Arctic's prospects and its location at the centre of this new border in international relations. Greenland's political elite only comprises 44 people however (nine ministers, 31 MPs and four mayors): hence a lobby of only 25 people is would be required to access Greenland's strategic assets. Suffice to say this is a small number for major companies and States who are accustomed to many more and who might be assisted in their approach since some of the 25 will not necessarily have an in-depth knowledge of the international stakes involved in this issue. This is why education is critical (which amongst other things enables the EU to take its interests forward by means of its soft power) likewise a better knowledge of international stakes, since the energy sector especially is of a global dimension. A crossroads for American, European and Asian interests in the region, Greenland has experienced an unprecedented interest in its territories on the part of many powers. This is a situation to which neither Denmark nor Greenland have been accustomed and this has led Denmark to take full interest in the Arctic. The historic visit by South Korean President Lee Myung-bak to Greenland in 2012, without him stopping off in Denmark and without the presence of the Danish Prime Minister, who is nevertheless responsible for Denmark's foreign and security policy, almost gave Greenland State status in the context of its international relations. And this has come about because of the sovereignty it acquired in 2010 in terms of managing its own raw materials.

The critical issue of rare earth supplies, a group of metals that is vital to the economy in the 21st century, particularly in view of a low carbon economy, has significantly enhanced the major economies' interest in Greenland. The USA, the EU, China and South Korea have all met the Premier of Greenland on this issue. The signature of a letter of intent aiming to form cooperation in the area of raw materials between the EU and Greenland during a visit by the European Commission's Vice-President, Antonio Tajani, to Greenland in 2012 raised great hope in terms of Europe's intention to secure its supply of rare earths via Greenland; this came about because of fear of an acquisition by China in an area in which the latter controlled more than 97% of the world production in 2012. This issue is all the more important since the EU depends entirely on imports in this strategic sector. In the face of the interest expressed by and the means available to powers like China, a certain amount of impatience on the part of Greenland seemed to emerge at the end of 2012 regarding the EU's ability to provide a rapid follow-up to this letter of intent. The visit in December 2012 to South Korea by a Greenland delegation after the visit of another Greenland delegation to China in November 2012 shows that the competition for access to Greenland's natural resources is a tough one and that it intends to diversify its partnerships notably by turning towards the Asian economies which are booming, whilst maintaining its wish to cooperate with the European Union.

Given these stakes, not forgetting the strategic dimension of the USA, via a military base in north Greenland (Thule) whose radar is a vital part of American defence, securing a strong economy in the event of Greenland's independence is a vital stake for future developments in the Arctic; it is also an area in which the EU may have a constructive role to play, in the interest of regional developments and the world's energy security. Iceland's experience during the world financial crisis shows that Arctic states need to stay economically strong. This is all the more true for an Arctic territory which is rich in natural resources like Greenland. Iceland, which because of this crisis became China's "entry point" into the Arctic did however succeed in recovering rapidly and assert its choices in terms of foreign investments on its territory. Taking the risk of a rapidly independent Greenland and which undoubtedly will not have taken the time to guarantee a strong economy on the long term, could impact future developments in the Arctic and the world's energy security. Leaving Greenland at the mercy of foreign economic assistance, which may very well come from a non-Arctic State and which might lead to the unofficial control of the territory's natural resource management policy is too great a risk, both for Greenland and for the Arctic States, as well as the world economy. The European Union has a role to play in this context: offering Greenland an economic "safety net" which the potential Greenlandic State may need in order to limit any possible economic difficulties as the annual block grant from Denmark would be withdrawn. Everything depends on the shape of the EU at the time of Greenland's potential independence (according to some in 20 to 30 years time).

Conclusion

The Arctic is developing into a key region in the 21st century and will have a major role to play in the world's economy. Because of the widespread impact of global warming in this region (rising sea levels, increasing CO2 levels in the atmosphere and because of the melting of the ice-sheet and the permafrost) all of the world's decision makers will have to acknowledge the Arctic is speeding up globalisation. Hence, the need for players in the region to develop their strategic research regarding the Arctic, which has been illustrated by a non-Arctic power like China. The European Union can but maintain its interest in the Arctic, and also seek greater constructive involvement. Although Iceland's membership of the EU would bring the number of EU's Arctic members up to four (half of the Arctic States), this was far from being a reality in 2012. In the face of the energy security issue for European industry the strengthening of relations between the EU and Greenland emerged in 2012 as a key issue in Europe's Arctic policy.

[1] European Commission, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, "Developing a European Union Policy towards the Arctic Region: progress since 2008 and next steps", Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, 26th June 2012, http://eeas.europa.eu/arctic_region/docs/join_2012_19.pdf

[2] Author's translation. Bo Lidegaard, "Hvis jeg var dansk statsminister, ville jeg udfolde mit yderste for at beholde Færøerne og Grønland inden for det danske rige", http://politiken.dk/politik/ECE1730971/hvis-jeg-var-dansk-statsminister-ville-jeg-udfolde-mit-yderste-for-at-beholde-faeroeerne-og-groenland-indenfor-det-danske-rige/, 19th August 2012.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :