Economic and Monetary Union

Alain Fabre

-

Available versions :

EN

Alain Fabre

Economist and historian

2011, Italy's return to Europe

With hindsight, 2011, which also coincided with the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of its unity, was a historic turning point for Italy. The 2013 elections will provide an initial answer as to the state of affairs.

In any event the replacement on 16th November 2011 of Silvio Berlusconi, who had been discredited both from a domestic point of view and also across Europe by Mario Monti, a kind of Italian Raymond Barre, whose personal record was flawless and who enjoyed undeniable legitimacy within the community, could, depending on what happens next year, turn out to be another "technical" interlude (as proven on several occasions with Ciampi, Dini) designed to provide temporary relief to political clientelism that finds it difficult to implement painful reforms or, on the contrary, it may open the way to a vital structural change. However we must not overstate the change caused by the rise to power of the former European commissioner. Since the start of the 1990's, after the "Mani Pulite" operation and the pressure exercised on the Italian leaders by the goal to join the euro, Italy has been engaged in a continuous process to adapt, as highlighted by its then public deficit that totalled 10% of the GDP. It was only with the 2008-2009 crisis that the scale and the pace of the necessary reforms accelerated to a degree that was beyond the response capability of political clientelism. This explains the call made for a technician responsible for a task of size, but which within political spheres, is still an interim period.

It remains nevertheless that at the turn of 2011 Italy made a real "comeback" to Europe. In the first place because the "particular" style adopted by the "Cavaliere" led to a decline in Italy's credibility within Europe and also because at a time when the euro zone was under pressure, notably because of the financial turbulence that emerged in the summer of 2011, all European leaders were aware that an attack by the markets against the Italian debt might have sounded the single currency's death knell. This was the reason, at the beginning of autumn 2011, behind the extreme tension between the Franco-German couple on the one hand, and the President of the Italian Council on the other. In this regard in the euro zone, the appointment of Mario Monti, beyond the consolidation of the Italian economy, was immediately considered to be a means to ease financial tension and to facilitate the integration process. In the series of events that marked the autumn of 2011, the appointment of the Governor of the Banca d'Italia, Mario Draghi, as President of the European Central Bank, which came almost at the same as Mario Monti's appointment must be deemed to be of primary importance. In their own right these two changes simply highlight the new eminent role to be played by Italy in the integration of the euro zone.

A case study for the assessment of growth strategies in Europe.

This is why the manner in which Italy will consolidate its financial situation and recover its competitiveness, in relation to the development of the Central Bank, that was started by Jean-Claude Trichet, towards a more important role as lender of last resort, will provide decisive lessons on how to define and achieve a growth strategy in Europe.

Unlike Germany, Italy does not appear as a typical economic model. Conversely, although its competitiveness has collapsed over the last ten years – this is one of the main challenges it has to rise to – Italy cannot be compared either with French budgetary laxity – it produces significant primary surpluses and a general deficit level that was under control prior to the crisis – nor with Spanish financial bubbles – its banking system does not require a community aid plan. It has a high yield productive base comprising a network of businesses, notably in the north of the country, which supports the comparison with their German competitors. However the country is literally in gridlock because of the debt which rises far beyond the levels of its immediate neighbours to a total of 123% forecast for the end of 2012.

The austerity/growth controversy that has hit Europe since the introduction of major consolidation plans in most places, will, in Italy, comprise a test for Europe. Criticism against generalised budgetary austerity in Europe, which is mainly based on neo-Keynesian analyses, found strong echo in the electoral campaign in France in the spring of 2012. This went so far that during the European Council on 28th and 29th June the new French leaders claimed to be the champions of this idea. The competitiveness strategy and the drastic reduction in deficits undertaken across Europe, is also leading to strong opposition on the part of the populations, who are the first to suffer reductions in public subsidies and measures to make the labour market flexible during a period of morose growth.

If Italy succeeds in re-establishing its basic conditions, of greater, competitive growth, it might be able to leave a stronger mark on the growth strategy for an integrating euro zone than Germany, the absolute, permanent reference, but which is bears the seal of exceptionalism in the minds of both its admirers and also its critics.

An exceptional plan to adjust public accounts

The effects of the 2008-2009 crisis led to a sharp increase in Italy's heavy handicap, i.e. public debt.

As of summer 2011 the national debt rose in terms of its rates and spreads, i.e. the premiums demanded in comparison with the German debt, considered by the markets as the euro zone's risk-free asset reference: from June to November 2011 the 10 year rates on the public debt rose from 4.8 to 7.3% i.e. a spread of 5.5 points in comparison with Germany. This significant rise in financial pressure on the budgetary authorities might have cancelled out the work already undertaken towards budgetary recovery and then potentially close access to the financial markets on the part of the Italian Treasury. The change in government and the adoption of a draconian reform plan immediately led to an easing in the financial pressure on Italy: from December 2011 to March 2012 the ten year rates decreased by 22 base points thereby reducing the spread with the German debt to 4.5 interest rate points.

The adjustment undertaken by Italy since 2010 is typified by its exceptional scale. Its implementation started before the appointment of the Monti government and it was the collapse of the Berlusconi government's credibility in the autumn of 2011 that led to the change in the executive. To a certain extent, since the beginning of the 1990's, the work undertaken by the Italian authorities has been continuous: from 1994 to 2007 the weight of the public debt in percentage of the GDP dropped from 124% to 103%. With the 2008-2009 crisis the work that had been done was wiped out and the burden of the public debt rose to 120% of the GDP in 2011.

In the space of two years the Berlusconi and Monti governments adopted five austerity plans representing a total effort of 258 billion €, i.e. 16% of the GDP in 2011: 25 billion € in July 2010, then 80 billion € one year later, on the initiative of the Finance Minister, Giulio Tremonti, against the opinion of Silvio Berlusconi. Under pressure from the ECB that threatened to stop purchasing Italian debt, a third plan to a total of 51 billion € was drafted in an emergency in August 2011. But the measures announced by the Berlusconi government were slow to be implemented and ostensibly played to the tune of political communication. Since he took office Mario Monti has introduced additional savings of 102 billion € over two plans – December 2011, July 2012 – the first totalling 76 billion €, the second 26 billion €.

In itself, with a primary surplus, before the payment of interest on the debt (2.5% of the GDP in 2008 and 1% in 2011), the public finance situation is initially of less concern that it is for example in France. It is the burden of the public debt, truly a dead weight to the economy that comprises the first constraint to relieve. In budgetary terms the interest rates represented nearly 5% of the GDP in 2011. With the new government's updated forecasts, which take the public debt rates up to 13% of the GDP in 2012, the imperative to adjust to a morose growth situation seem all the more urgent. The Italian executive intends to adhere to its goal of bringing the public debt rate down to 100% in five years i.e. an effort of 3% of the GDP initially and nearly 5% of the GDP at the end of this period. In a bid both to contain the negative effects on growth and to avoid a return in 2013 to a policy hostile to reform, the heaviest parts of the plans mainly focus on the post-election period: 49 billion € in 2012, 76 billion € in 2013 and 81 billion € in 2014.

With an economy in recession, with the GDP registering negative fluctuations since the second quarter of 2011, the expected public deficit balance threatened to be off course mainly due to the burden of interest charges drifting between 2011 and 2012, from 4.9% to 5.3% of the GDP because of soaring rates. All of the measures decided upon aim to strengthen the creation of primary surpluses which should total 3% of the GDP in 2012 and 4% in 2013. Hence according to the budgetary authorities, after a deficit of 3.9% of the GDP in 2011, Italy may very well drop below the 3% mark in 2012 to return to 0.5% in 2013. As of 2014 and 2015 it is due to record an overall public account surplus thanks to a primary result of 5% of the GDP.

As a whole, until July 2012, the government privileged the mobilisation of new resources – from privatisations – the sale of public real estate assets – totalling 2/3 of the adjustment effort. From this point of view Mario Monti's second plan dating 9th July last heralds a clear change in direction since the effort announced and prepared for with the aid of Enrico Bondi, which was typified by the recovery of Montedison and Parmalat, focuses almost exclusively on spending.

The plan chosen this summer, based on the general review of public policy introduced under Nicolas Sarkozy in France, anticipates a sharp reductions in staff in the central administrations of around 20% in terms of executives and 10% of other staff, i.e. a reduction of 4.5 billion € for the duration of the plan. Amongst the main measures announced is the reduction of healthcare spending with, amongst others, the closure of 18,000 hospital beds, representing an effort of five billion €; funds granted to local authorities will be cut by nearly 10 billion. These savings measures will also enable the Monti government to relinquish the competence acquired by the Berlusconi government of raising VAT rates on October 1st next from 21% to 23%.

In order to assess the recovery policy introduced by the Italian authorities we should point out that the burden of spending and deficits are close to German levels, which are not same as those seen in France. Since it joined the euro zone Italy has succeeded in moderating both the burden of public spending as well as that of mandatory levies. From 2000 to 2008 the rate of Italian public spending rose from 45.9% to 48.6% whilst in Germany this rate dropped from 45% to 44%. At the same time it rose in France from 51.7% to 53.3%. During the crisis this rate rose in all three countries. In 2011 it dropped under the 50% mark after having risen above this level in 2009 and 2010, and this, in spite of a 6% GDP contraction since 2008. In the same year Germany stood at 45.6% and France at 56%.

Regarding mandatory levies, in 2000 Italy lay close to the German level (41.5% against 41.3%), whilst France (44.2%) rose above this rate by 3 points. However for want of an effort comparable to that of Germany in terms of spending, Italy was unable to achieve a similar reduction: in 2008 the German rate returned to 39% and in 2010 it was down to 38%, whilst in Italy it rose to 42.3% in 2010 (42.7% in 2008). In France it rose to 43.2% in 2008 and 42.5% in 2010.

Depressed Domestic Demand.

In the work it is undertaking the Italian government finds itself on a narrow path. It has to make its action credible amongst the community institutions and the financial markets, and contain the recessive effects of the measures taken and also avoid starting a vicious circle of a contraction in activity and an increase in adjustment requirements.

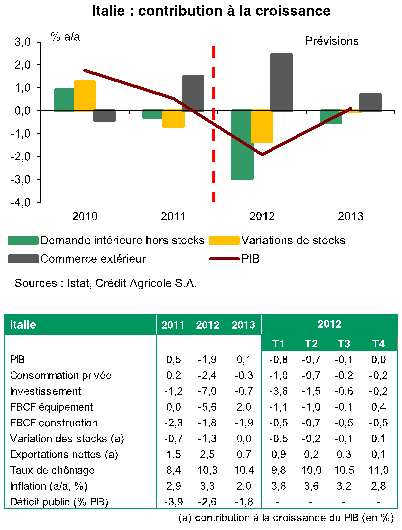

As with many strategies of this type the effects of consolidation long term are supposed to help stem short term recessive effects and create a sound growth dynamic. After a sharp contraction of the economy in 2009 (-5.5%), similar to that in Germany (-5.1%), Italy experienced a net recovery of activity in 2010 (+1.8%). In 2011, in spite of slow progress over the entire year (+0.1%), the economy entered recession. Since the start of 2012 contraction has continued: -0,7% in the first quarter, - 0,8% in the second quarter, which seems to be setting the annual pace at around -2/-2.5%. In 2013, it seems reasonable to forecast a stabilisation of activity and a containment of recessionary effects. As with the usual consequences of adjustment policies, it is domestic demand that suffers the most immediate, far reaching effects of adjustments made to the entire economy. Private consumption, which comprises 60% of the GDP, clearly contracted due to the pressure on incomes and an increase in unemployment. After having risen by 0.2% in 2011, it has been declining since the second quarter of last year: it is due to experience a net decline in 2012 (-2.4%) and stabilise in 2013 (-0.3%).

Investments dropped sharply, notably in companies with fewer than 10 employees, which are suffering the most from the contraction in domestic demand and from a tightening in access to credit. Manufacturing investment contracted by 3.6% in 2011. Its decline is concentrated amongst businesses with under 200 employees (-7.5%) whilst it is rising amongst those with between 200 and 500 staff (+2.5%). In 2012 its contraction is said to lie at nearly 10%. Down in 2011 (-1.2%), investment in all businesses is due to decline sharply in 2012 (-7%) and continue in 2013 (-0.7%).

The compression of domestic demand weighs heavily on industrial output that declined by 25% in 2008-2009 and which is still 20% below its pre-crisis level. The difference in terms of the pre-crisis period in France is 10% and in Germany 3%.

The unemployment rate that had dropped down to 6.1% in 2007 rose significantly because of the crisis, the contraction in activity and structural burdens affecting the labour market. It lay at 8.7% at the end of 2010 and 9.6% at the end of 2011. The rise in unemployment continued until the start of 2012 (10.7%).

An effective productive system facing a decline in competitiveness in the 2000's.

However recessionary effects, combining the burden of the crisis and the measures designed to consolidate the Italian financial situation should not mask emerging structural perspectives. The corrections of imbalances in the Italian economy are, above all, part of the construction of a more viable, i.e. competitive growth strategy. Deprived of inflation and devaluation levers Italy now has to make real adjustments. By doing this it is laying the foundations for sound, balanced mid-term growth. The Italian public debt which corresponds to years of deficit is above all the result of accommodating to political clientelism. It was the blow dealt by market pressure to this mode of political power and the dangers to which it finally exposed the entire country, which led to the change in executive in the autumn of 2011. For want of a solution in inflation and devaluation, the Italian political classes were forced to resolve to a consolidation programme as typified by the Monti government's line of action.

It is common to assimilate an improvement in the situation with GDP growth and vice-versa. This is even truer with consumption. Hence the slightest contraction is commented on with consternation by most observers. Moreover, sensitivity to Keynes provides theoretical credibility to this widespread belief. However what has typified the development of the entire world and European economy over the last twenty or thirty years has been a significant tolerance to imbalances which has also found powerful support in financial globalisation: if imbalances find funding then it would appear important not to reduce them. The thing that the crisis so brutally revealed was the wall that most western economies were facing i.e. destructive mid-term effects on productive wealth growth, on potential economic growth in general and finally there was the risk of economic downgrading. Even in the age of financial globalisation a developed economy cannot possibly support permanent imbalance. The inventory effect – which corresponds to an accumulation of old debt – will at some point impede the development of an economy with all of the consequences that this entails as far as unemployment and living standards are concerned. Like many other countries in Europe Italy is a perfect illustration of situation in which debt – especially at this level – leads to depressive effects and makes any truly viable growth impossible. This is why, for Italy and likewise for its partners, the assessment made of the economic situation has to focus on the way and the degree to which structural imbalances are absorbed more than on economic variations in consumption and of the GDP. An increase might mean a worsening in the situation and a contraction, an improvement. The important thing for an economy that wants to foster growth and sustainable employment is its ability to make them real, healthy and balanced. In the end public and external deficits are the evidence of an imbalance between consumption and savings: their resorption or their control are the conditions for true mid-term growth.

Hence the importance of the development of the external balance; due to the effects of a compression in domestic demand and also the development of the euro exchange rate that favours export price competitiveness, foreign trade contributes positively to continued growth. After a sharp contraction in the deficit over 21 billion € in 2010, down to 16.6 billion in 2011, the trade balance was almost balanced in the first half of 2012, due to a marked decline in imports (-6%) and an increase in exports of over 4%. Although exports towards the 27 have been stable because of the economic cycle in Europe, Italy, like Germany was able to take advantage of greater dynamism of the emerging economies. From January to June 2012 exports to countries outside of the EU rose by 10% in comparison with the first half of 2011. Energy aside, Italy is making significant surpluses: 43 billion € in 2011, 33 billion € in the first half of 2012. With the EU countries Italy registered a surplus of 5.1 billion € between January and June 2012 against a deficit of 2.7 billion € in 2011. With Germany its deficit is limited to 3 billion € (- 13 billion € in 2011) whilst the surplus with France totalled nearly 6 billion € (+10.3 billion € in 2011) and that with the UK totalled 4.6 billion € (+6.9 billion in 2011). With non-European countries Italy registered a deficit that has mainly been caused by energy products. Energy aside Italy's foreign trade makes profits: + 39 billion € in 2011, +27 billion € in the first half of 2012.

If we look at mid-term developments we can see that Italy has succeeded in limiting the erosion of its world export market share: it has not done quite as well as Germany but much better than France. From 2002 to 2011 the world market share in terms of value contracted in Germany from 9.4 to 8.6% (-0.8), in Italy from 3.9 to 2.9%, (-1), in France from 4.8 to 3.4% (1.4). Italy's share in EU exports fell slightly in 2010 in comparison with 2000 (10.6% against 11.8%) whilst it rose in Germany (27.7% against 24.8%) and it fell significantly in France: down to 10.7% against a previous 14.7%. Italy now weighs the same as France in terms of European exports. Compared to German exports, those in Italy are on a level with those from France (38%) which has witnessed the collapse of its ratio. Ten years ago French exports represented 60% of those from Germany and Italy 47%.

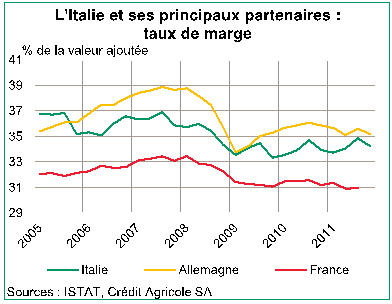

Although Italy's export positions have suffered less than France's it remains however that its competitiveness has declined significantly over the last ten years. This situation first relates to the competitiveness of its prices that has led to rising labour costs and decreasing productivity. Over the period 2005-2011 unit labour costs have risen similarly in France and Italy (+13.2%) whilst their increase was limited to 5.3% in Germany. However in 2010 and 2011, whilst they increased in France by 0.6% and 1.6% respectively, they developed at almost the same rate in Italy and Germany: - 0.5% and +1% for the former, -1.1% and +1.4% for the latter. It remains that Italian labour costs are still less than in Germany and France. Hourly labour costs lay at 27€ in Italy in 2011, against 30€ in Germany and 34€ in France. In terms of productivity Italy suffered a decline of 2.7% from 2005 to 2011, whilst France (+2.8%) and Germany (+4.4%) registered a rise. Above all these developments reflect the pre-crisis situation. Trends have been more favourable since 2010. Industrial productivity, after having recovered well in 2010 (+10%) continued to progress more moderately in 2011 (+0.5%).

However, the vitality of Italy businesses, notably in industry, is still of decisive importance in the consolidation now ongoing. Whilst the industrial share in value added has collapsed in France over the last ten years, dropping from 18% in 2000 to 13% in 2010, it totals 19% in Italy against 23% in 2000. Over the same period its erosion was contained in Germany: 23.8% against 25.3% at the beginning of the decade. The weight of Italian SME's in exports is greater than in France or Germany where it is mainly concentrated amongst large companies.

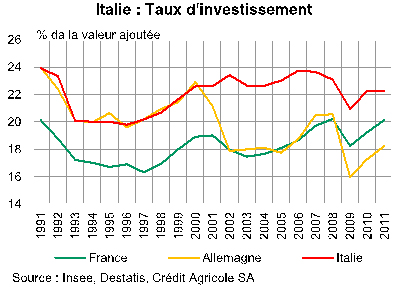

The investment rate has remained high and stable over the last ten years (22.7%), higher than in Germany (18%) and France (19%). Moreover Italy distinguishes itself by a gross margin, gauged as a share of the gross operating surplus in value added, i.e. a share not devoted to employees, on a level with Germany (41% in both cases) and clearly higher than in France, (30%). The burden of social charges in terms of the GDP is lower in Italy (13.4%) than in Germany (15.5%) and France (16.7%).

Business financial structures are suffering because of the recession. But the companies which experienced a sharp rise in their financial debt, totalling 180% of the value added in 2008 against 110% in 1998, have now stabilised this. Businesses' financial debt/GDP ratio is much lower in Italy than in France, the UK and Spain. Dependency on credit is especially high amongst small companies under 10 employees whose contribution to exports is only slight.

Promoting innovation in businesses and completing structural reform

Beyond the consolidation of public accounts the government is trying to raise growth potential via structural reform. Monti's government intends to make the labour market more flexible by addressing corporatism – pharmacies, taxi-drivers – by removing impediments to employment. Italy is typified by a high segmentation of its labour market. Hence the unemployment rate in the North of Italy totals 7.3% and in the South 17%; youth unemployment lies at 34%. In the North of Italy the activity rate of the 15-64 years olds lies at 64% against 53.4% in the south.

At the beginning of 2012 the government took a series of measures that were designed to reduce obstacles to employment. The leading measure concerns the application of article 18 of the labour law regarding dismissals with the substitution of a compensation formula by an obligation to re-integrate as stipulated by the legal regime in force.

The collapse of Italian business competitiveness in the 2000's was mainly due to the extreme fragility of their investments in innovation. The share of R&D compared to the GDP is not over 1.3% in Italy whilst it stands at 2.3% in France and 2.8% in Germany. The difference with European levels comes from the lack of investment on the part of the private sector, which is no more than 0.5% of the GDP. Amongst the 500 main European businesses involved in R&D, only 17 of them are Italian, and even these are extremely large groups (Fiat, Eni, Finmeccanica, Pirelli, Telecom Italia). Italy's commitment to new technologies is weak. Likewise Italy lies well below Germany and France in terms of its ability to attract international investments. They generally total 0.5% of the GDP against around 5% in the "big" countries of the EU.

To stimulate corporate innovation, the government has decided to encourage capital flows into business by offering income tax incentives and capital increase investments. In similar vein, a robust effort will be put into simplifying administrative procedures for the companies launched.

The government also wants to develop and modernise infrastructures which are often ageing in Italy – and are now a priority in fostering the reduction of regional differences. Investments in infrastructures, which comprised one of the main components in the Italian miracle until the 1980's, slowed greatly after this and public spending was mainly used to feed clientelism. The motorway networks have aged likewise the railways. Dependent on energy imports to a total of 85% Italy has not invested much in these areas, notably regarding electricity. France provides 17% of its electricity requirements, the price of which is over European levels by 45% for private parties and 33% for businesses. The same applies to the distribution of water hence the difficulties, especially in the south – during the summer water supplies are intermittent – which penalise agriculture.

Credibility restored but after long hard struggle

After experiencing a period of easing in the wake of the appointment of Mario Monti as President of the Council until March, the financial markets again toughened the yields on the Italian debt as of the spring because of the anticipated effects of the adjustments on the extent of the economic recession and its effects on the completion of the deficit resorption programmes. To this we might add uncertainties over the management of the euro zone crisis by its institutions (ECB, Council, Eurogroup, Stability Fund). Without returning to the levels of November 2011 interest rates became tense once more rising to 6% at the beginning of the summer.

The new plan in July 2012, the positive reception of the decisions taken by the European Council on 28th and 29th June last, notably in terms of banking integration, likewise Mario Draghi's declarations that indicated that "the euro is irreversible" [1] announcing his intention to do everything he could to save the single currency, helped stabilise the markets. At the end of August however tendering over short term maturities heralded the start of true easing, with the trend growing as the Central Bank announced that it was prepared to make unlimited purchases of public debt. On 7th September 10 year rates returned to 5.26% i.e. the milestone low recorded in March last.

Undeniably the Italian economic policy is enjoying the credibility lent to the new government, as well as the turn in terms of budgetary integration and the development in the intervention conditions on the part of the Central Bank.

The first result of Monti's government is probably to have succeeded in combining internal consolidation and reform efforts with the spinoffs on debt management i.e. greater integration and solidarity. This strategy is also benefiting from the Central Bank's move towards becoming the lender of last resort in its own right. This change makes a decisive contribution to the coherence of the Italian strategy as a whole. The President of the Council believes that European solidarity, as notably illustrated by the intervention of the ECB on States' debts when they undertake the reform required in view of reducing their interest rates, should "reward" the work undertaken from a domestic point of view. Hence his repeated determination not to launch European aid measures in support of his country and his simultaneous criticism of the excessive rates applied to the Italian debt and likewise the very low ones implemented on the German or French debt. Mario Monti believes that these two are contributing towards a market anomaly.

If at the end of the day the government succeeds in reversing market expectations to launch the progressive easing of the Italian rates long term, the combination of the drastic adjustment of accounts and increased competitiveness should lead to cumulative virtuous effects thereby enabling a rise in growth potential: one rate point less represents an annual alleviation in interest rates of nearly 20 billion €, 1.2% of the GDP! In all Italy seems to have skilfully manipulated the virtues of European integration in order to embrace fully its own internal structural problems. If only by reason of the burden of its abnormal debt, it is probable that Italy will remain on course for at least ten years to reach the same level as its major partners.

With Monti's government Italy has again set itself front stage in Europe and the recovery of its economy might, in the long run, simply strengthen its influence in terms of managing the euro zone. We can see this via the number of meetings between Mario Monti and Angela Merkel, Mariano Rajoy and François Hollande in which Italy is taking a more active role in steering the euro zone. In all, for want of another model, notably regarding its partners who still wince at the words, austerity and competitiveness, Italy might very well become an example.

[1] Le Monde, 22-23 July 2012.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :