Democracy and citizenship

Xavier Groussot,

Laurent Pech,

Tobias Lock

-

Available versions :

EN

Xavier Groussot

Laurent Pech

Tobias Lock

A Long Time in the Coming

As amended by the Lisbon Treaty, Article 6(2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) provides that the European Union "shall accede" to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of 4th November 1950 (commonly known as the European Convention on Human Rights - ECHR) [1].

This provision, which requires EU action ("the Union shall accede"), is the fruit of a long and convoluted history. [2] Without entering into further details, the fact that the European Economic Community (EEC) was primarily concerned with economic integration was understood at the time of the drafting of the Treaty of Rome as a sufficient reason not to seek EEC accession to the ECHR or to adopt an EEC bill of rights providing for the integration of the substantive provisions of the ECHR. As is well known, the lack of comprehensive provisions for the protection of human rights has not meant the absence of any protection in the EEC legal order. As early as 1969, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) held that fundamental rights were enshrined in the general principles of EU law—strictly speaking EEC law at the time—that the Court protects. In its subsequent case law, the ECJ has further recognised the "special significance" of the ECHR amongst international treaties on the protection of human rights, so much so that since the early 1990s, the Court regularly refers to the provisions of the ECHR and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to decisively guide its interpretation of EU law whenever it has to adjudicate on fundamental rights issues. However, in the absence of formal EU accession to the ECHR and strictly speaking, the ECJ has still no jurisdiction to apply the ECHR when reviewing EU law because the ECHR is not itself part of EU law.

Influential political actors have always believed that EU accession to the ECHR would fill significant gaps in the EU's system for protection of human rights by providing a minimum standard and an external check. Since the first proposals for accession of the EEC to the ECHR appeared in the late 1970s the European Commission has repeatedly sought to be allowed by the Council to negotiate an accession agreement with the Council of Europe. [3] Asked by the Council to deliver its opinion on the question of whether the EU had the competence to seek accession on the basis of the EU Treaties as they stood at the time, the ECJ held in 1996 that EU accession to the ECHR would result in a substantial change to its system for protection of human rights, which meant that the EU lacked the power to become a party to the ECHR. [4] In other words, the ECJ told the EU Member States that they needed to amend the EU Treaties before seeking accession. The Court's opinion obliged European institutions to rethink how to affirm the EU's commitment towards fundamental rights and clarify the arguably complex relationship between the EU, ECHR and national legal orders as well as the no less complicated relationship between the Luxembourg and Strasbourg Courts. [5]

When the time came to drafting a "Constitution" for Europe, virtually all members of the so-called European Convention presided by Valéry Giscard d'Estaing agreed that the adoption of a legally binding EU Charter of Fundamental Rights – first "proclaimed" by EU institutions on 7th December 2000 – and EU accession to the ECHR "should not be regarded as alternatives, but rather as complementary steps" [6] because the Charter and the ECHR had different purposes. In other words, while the EU Charter is primarily aimed at the EU institutions, it does not preclude accession to the ECHR as in its absence, EU actions, including the rulings of the ECJ, cannot be subject to the additional, external and specialised monitoring of the Strasbourg system and in particular the control of the ECtHR. EU accession has been therefore defended on the main legal ground that it would finally afford natural and legal persons protection against EU acts similar to that which they already enjoy against national measures. The EU would then be in a situation analogous to that of any of the EU Member States, the ECJ in a situation analogous to that of any national courts of last resort, and the Charter itself would then be in a position similar to the one occupied by any national bill of rights. Additional legal and political arguments in favour of EU accession – the force of which may however be variable – have been made but space constraints preclude any exhaustive overview. Suffice it to say that beyond the need to establish and guarantee a more coherent and harmonious system for protection of human rights in Europe, EU actors have always been particularly keen to secure EU accession to the ECHR for political and symbolic reasons. In other words, EU accession has been repeatedly presented as an essential step that would solemnly confirm the EU's commitment to the protection of fundamental rights both internally and externally. Because these arguments were prevalent before the drafting of the "EU Constitution" and continued to be seen as valid by the most influential EU players, the EU Member States agreed that the Lisbon Treaty should reproduce the relevant provision previously to be found in the EU Constitution, according to which the EU shall become a party to the ECHR.

Thanks to the necessary Treaty amendments envisaged by Opinion 2/94 having been finally undertaken and the Council of Europe's own revision of the ECHR, [7] joint talks between the European Commission and the Council of Europe were organised a few months after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1st December 2009. In these discussions, the Commission acted on behalf of the whole EU following the negotiating mandate it secured from the meeting of EU Justice Ministers in the Council of Ministers on 4th June 2010. [8] The previous month, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe – not to be confused with the EU Council of Ministers – gave an ad-hoc mandate to its Steering Committee for Human Rights (CDDH) and to elaborate with Commission officials the necessary legal instruments for the accession of the EU to the ECHR. An informal working group consisting of legal experts from the Commission and from fourteen countries belonging to the Council of Europe was then constituted. A total of eight working meetings took place between July 2010 and June 2011. A rough draft agreement was first produced in February 2011 but a number of unresolved legal issues required further discussion and it was not until 19th July 2011 that a fully-fledged version of the draft agreement on the accession of the EU to the ECHR, consisting of 12 amending articles, was published alongside an explanatory report. [9] The draft and explanatory report were subsequently finalised at an extraordinary meeting of the CDDH held on 12th-14th October 2011. [10]

This Paper will first recall the most contentious points debated before and during the drafting of the draft accession agreement before offering a critical review of how these points were addressed by the Commission and Council of Europe's experts. It will conclude with a brief overview of the expected timetable for the ratification of the agreement and the procedural requirements governing such a process.

1. Overview of the Most Contentious Issues

Whilst Article 6(2) TEU provides that the EU must accede to the ECHR, some EU Member States thought it necessary to include a caveat whereby such accession shall not affect the Union's competences as defined in the EU Treaties. This concern also explains why a legally binding protocol setting out further constraints or safeguards – depending on one's point of view – which the future accession agreement must take into account, was furthermore annexed to the European Treaties. Known as Protocol no. 8, [11] this document further reiterates the point that EU accession shall not affect the competences of the Union or the powers of its institutions and more intriguingly, also provides that the specific characteristics of the EU and EU Law must be preserved yet it does not define them. [12] As a result, its precise scope remains quite a mystery but it was clear from the start that this Protocol would significantly constrain the drafters of the accession agreement. Indeed, it not only implicitly demands that the autonomy of the EU legal order be preserved but also includes institutional elements such as the obligation to preserve "the specific arrangements for the Union's possible participation in the control bodies of the European Convention" and procedural elements by providing that any agreement ought to offer "mechanisms necessary to ensure that proceedings by non-Member States and individual applications are correctly addressed to Member States and/or the Union as appropriate." These institutional, substantive and procedural issues, and the different options debated before and during the drafting of the draft accession agreement will now be considered.

1.1 Institutional Issues

Two institutional issues proved particularly divisive: the one judge per high contracting party rule and the possibility of EU participation in the Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers. In both instances, the question was essentially whether the EU should accede to the ECHR on an equal footing with the other high contracting parties.

1.1.1 The one judge per party rule

From an institutional point of view, a recurrent argument has been that Protocol no. 8 requires first and foremost the appointment of an EU judge to ensure both adequate representation of the EU within the Strasbourg Court and specialised expertise on the "specific characteristics" of EU law. Any agreement of the question of whether the EU should be entitled to have a judge sit in the Strasbourg Court like any other contracting party does not exhaust the discussion. Indeed, several positions have been defended with respect to the extent of the EU judge's mandate. Broadly speaking, two options were available: the EU judge's mandate could either be similar to the other judges' terms of office – in the Strasbourg system each contracting party is represented by one judge – or the EU judge's role could be more limited, which could mean, for instance, that the EU judge would only sit on EU law-related cases and have a mere consultative function in non-EU related cases. This latter option however was subject to criticism on several grounds: it would breach the principle of judicial independence, be impracticable as one would have to decide whether each particular application raises points of EU law, and go against the idea of having the EU acceding to the ECHR on an equal footing with the other contracting parties.

The selection process has also been particularly debated. The drafters of the accession agreement were once again presented with two main options: either rely on the traditional procedure of the Convention system to appoint the new EU judge – whereby judges are elected by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) from a list of three candidates submitted by the contracting party – or let the EU decide on how the EU judge should be selected and appointed and only allow the PACE to take note of the EU's nominee. The European Parliament strongly favoured this first option. It further made clear its wish to be associated to the short listing process to be conducted by the European Commission and/or the Council of the EU – a problem for the sole EU to solve – and to appoint a certain number of representatives to the PACE in order to participate in the election of judges to the ECtHR. Indeed, and this constituted an additional problem to address: since the EU is not supposed to become a party to the Council of Europe, it would not normally be represented in the PACE.

1.1.2 EU representative on the Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers

The possibility of an EU permanent representative being part of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe has also proved particularly contentious. In a few words, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe is empowered to perform various tasks. Perhaps most significantly, it monitors respect of commitments by the contracting parties and supervises the execution of the ECtHR's judgments. The European Commission naturally argued in favour of having a representative sitting on the Committee of Ministers but non-EU countries were concerned that the EU and its Member States may seek to coordinate their votes and hence control – and block – the proceedings within the Committee of Ministers were they to adopt a common position regarding, for instance, the fulfilment of obligations either by the EU or one of its Member States. Several proposals were therefore made to limit the EU representative's right to vote in the Committee of Ministers to issues or cases involving EU law only.

1.2 Substantive Issues

1.2.1 Potential review of EU primary law by the ECtHR

Natural and legal persons in the EU cannot currently lodge a complaint before the ECtHR when they consider that their human rights have been violated by acts adopted by EU institutions (so-called EU secondary legislation). The ECJ, however, clarified early on that respect for human rights is a condition of the lawfulness of EU acts. [13] By contrast, the ECJ lacks the power to examine the compatibility of EU primary law – to put it simply, the provisions contained in the EU Treaties – with human rights standards. EU accession to the ECHR would however enable the Strasbourg Court to review the compatibility of any provision of the EU Treaties with the rights set out in the ECHR. Indeed, the ECtHR has not refrained from reviewing the compatibility of domestic constitutional law with the ECHR. [14] Concerned about the possibility of a judgment of the ECtHR leaving no choice to the EU Member States but to amend the EU Treaties, a particularly cumbersome process as the Lisbon Treaty ratification saga proved, the French government has argued that the accession agreement must exclude any review of EU primary law in Strasbourg. But this would run counter to normal practice and would be difficult to reconcile with the fact that the ECtHR has already reviewed national measures that apply or implement provisions of EU primary law. [15] It would finally conflict with the EU's advertised objective of sending a strong message of the EU's commitment to the protection of human rights within and outside the EU.

1.2.2 Future of the "Bosphorus test"

An additional significant question that most experts wished to see resolved by the accession agreement concerned the "equivalent protection test" devised by the ECtHR in its case law. [16] In a few words, the Strasbourg Court made clear in Bosphorus that it had the jurisdiction to review applications directed against national measures that directly or indirectly implement or derive from EU law obligations. In doing so, the ECtHR gave itself the power to indirectly review the compatibility of EU acts with ECHR standards. The Strasbourg Court's default position, however, is that the EU protects fundamental rights in a manner that can be considered equivalent to that for which the ECHR provides. In other words, the Strasbourg court would normally abstain from exercising its jurisdiction in cases where a Member State had no discretion in implementing its obligations under EU Law. The presumption would be in place for as long as the EU offers substantive guarantees and a controlling mechanism that are equivalent to those provided by the ECHR and unless there was a manifest deficit in the protection offered by the EU in the concrete case before the ECtHR. A comparable presumption of compatibility does not exist, however, in relation to any of the state parties to the ECHR regardless of whether they may possess a highly sophisticated and protective national system of protection of fundamental rights.

EU accession to the ECHR has often been presented as the perfect opportunity to clarify whether the ECtHR's rather deferential approach should be dropped or, on the contrary, extended post EU accession. Those in favour of abandoning the "Bosphorus test" contend that the Council of Europe should not tolerate any double standard between the state parties to the ECHR and the EU, and that the presumption of compatibility in favour of EU measures should end. An extension of the Bosphorus approach to all EU measures would mean, by contrast, that EU regulations, for instance, would be subject, similarly to national measures that are linked to the implementation of EU law obligations, to an unusually low degree of judicial scrutiny in Strasbourg. In any event, many hoped that the drafters of the accession agreement would seek to clarify the future of the Bosphorus approach and we shall return to this issue to see if their wish has been answered.

1.2.3 EU Accession to the ECHR Protocols

Protocol no. 8 requires that any accession agreement must ensure that EU accession does not affect the competences of the Union. This issue of competence proved particularly salient in relation to the potential effect of EU accession with respect to the ECHR Protocols that have not been ratified by all the Member States of the EU. Currently only Protocols no. 1 and 6 are binding on all Member States. Some countries such as the UK have expressed concerns that EU accession may lead the EU Member States to be automatically bound by all the ECHR Protocols regardless of whether they have ratified them or not, which, it has been alleged, would contravene Protocol no. 8.

Amongst the most significant additional protocols to the ECHR, one may mention Protocol no. 1 on the right to peaceful enjoyment of one's possessions, the right to education and the right to vote, Protocol no.6 on the abolition of the death penalty and Protocol no.12 which sets out a general prohibition on discrimination. Because these legal documents setting out additional rights are directly linked to the ECHR, it would seem sensible to ratify them as an ensemble or at the very least, sign up to all the protocols that concern rights contained in the EU Charter. However, the EU Member States, anxious not to allow for any undue extension of the EU's competences, forcefully argued for the EU to only immediately accede to the ECHR Protocols that have already been ratified by all of its Member States (such as Protocols nos.1 and 6). To guarantee some degree of flexibility post accession, it was also suggested that the EU should be allowed to take separate decisions whether to become a party to all or some of the Protocols after the EU had become a party to the ECHR itself.

1.2.4 Autonomy of the EU legal order and interpretative autonomy of the ECJ

The principle of autonomy of the EU legal order is closely linked to the role and place of the Court of Justice. "Interpretative autonomy" signifies that only the institutions of the particular legal order are competent to interpret the constitutional and legal rules of that order. [17] It has been always clear that no accession agreement undermining the autonomy of EU law or affecting the essential powers of the EU institutions would be acceptable for the EU, which means, for instance, that the ECtHR cannot be given jurisdiction to interpret the Treaties or rule on the validity of EU acts in a binding fashion.

With respect to the interpretative autonomy of the ECJ, however, the potential impact of the accession agreement has been perhaps exaggerated. Indeed, it is well established in the case law of the ECtHR that it is primarily for the national authorities, and notably the national courts, to interpret and apply domestic law. The ECtHR has also made clear that the same reasoning is applicable to international Treaties, and in this respect it is not for the Strasbourg Court to substitute its own judgment for that of the domestic authorities. The position of the Court of Justice would therefore be analogous to that of national constitutional or supreme courts in relation to the Strasbourg Court at present. Furthermore, the ECtHR does not rule on the validity of national law but issues declaratory judgments on the compatibility of relevant domestic law with the Convention on a case-by-case basis and in concreto. In other words, the ECtHR, unlike the ECJ, was never going to gain the power to annul an EU act. It may merely be able to state the incompatibility of the act with the ECHR in a declaration, leaving it to the EU to draw the consequences. It is for the EU to assess the consequences of the Strasbourg Court's judgment, which thus allows the EU to retain full control of its law, provided that it complies with the Convention. The application of the traditional principles above mentioned should therefore preclude any major problem as regards the interpretative autonomy of the ECJ.

1.2.5 Autonomy of the EU legal order and exclusive jurisdiction of the ECJ

EU Protocol no.8 demands that any accession agreement must ensure that EU accession does not affect inter alia the powers of its institutions. This primarily reflects the concern that the Court of Justice could be deprived of its exclusive jurisdiction in deciding on the allocation of powers between the Member States and the EU. This explains why the mechanism of inter-state complaints provided by Article 33 of the ECHR has been a particularly salient source of concern for those wishing to preserve the autonomy of the EU legal order and the authority of the ECJ. It has been repeatedly argued that this principle of autonomy requires that no change should be allowed in relation to Article 344 TFEU whereby EU Member States "undertake not to submit a dispute concerning the interpretation or application of the Treaties to any method of settlement other than those provided for therein." In other words, it was suggested that while there should be no restriction on non-EU countries initiating proceedings against the EU in the Strasbourg Court, the principle of autonomy of the EU legal order requires that EU Member States be precluded from involving non-EU institutions in the context of disputes solely concerning the interpretation or application of EU law. Such disputes are subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the ECJ. Another major source of contention concerned the potentiality of a scenario whereby a complaint relating to a judgment issued by a national court of last resort and making application of provisions of EU law would be lodged before the Strasbourg Court without any prior intervention from the Luxembourg Court. Because this scenario essentially called for a procedural solution, it will be examined below.

1.3 Procedural Issues

1.3.1 Exhaustion of domestic remedies and the need for a mechanism allowing the Luxembourg Court to deliver a ruling prior to the Strasbourg Court

In a highly unusual and therefore significant move, the ECJ published a "discussion document" on 5th May 2010 in which it clearly indicated that it would be undesirable to allow the ECtHR to decide on the compatibility of a Union act with the ECHR in the absence of any prior ruling from the ECJ on the validity of the Union act. [18] The Luxembourg Court was essentially concerned with a scenario whereby an applicant challenges a national measure implementing EU law before domestic courts without the national court of last resort making a reference for a preliminary ruling under Article 267 TFEU. As the Court put it itself: It is not certain that a reference for a preliminary ruling will be made to the Court of Justice in every case in which the conformity of European Union action with fundamental rights could be challenged. While national courts may, and some of them must, make a reference to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling, for it to rule on the interpretation and, if need be, the validity of acts of the Union, it is not possible for the parties to set this procedure in motion. Moreover, it would be difficult to regard this procedure as a remedy which must be made use of as a necessary preliminary to bringing a case before the European Court of Human Rights in accordance with the rule of exhaustion of domestic remedies.

It might be useful to briefly recall that natural and legal persons wishing to lodge a complaint with the Strasbourg Court must indeed first exhaust all the domestic remedies available in the State concerned. [19] In other words, and to oversimplify, anyone alleging a violation of one or several of the rights set out in the ECHR must obtain a decision from the relevant national court of last resort before lodging an application. This requirement reflects the idea that it is first and foremost the responsibility of the individual states to ensure that human rights are effectively protected. Furthermore, the requirement presents two advantages: it reduces the case load of the ECtHR and offers each contracting party the opportunity to remedy violations internally before any eventual reprimand by an international human rights court.

With respect to judicial proceedings brought directly before the EU courts, it has always been clear that EU accession would not create any procedural problem. Any natural or legal person seeking to directly challenge the legality of a legally binding Union act must lodge an application with the EU General Court. As a result, prior intervention of a Union court is guaranteed before any further complaint lodged with the Strasbourg Court. The situation is more complex with respect to the ECJ's jurisdiction to give preliminary ruling at the request of courts or tribunals of the Member States on the interpretation of Union law or the validity of acts adopted by the EU institutions. Since individuals have no way of forcing a national court to make such a reference, even where an obligation to do so exists under EU law, an individual's case may well be decided without a prior decision by the ECJ even if the case raised an issue regarding the compatibility of EU law with the ECHR. Provided that one agrees not to view the preliminary ruling procedure as an available remedy which an individual would have to exhaust, it would then be indeed possible to bypass the intervention of the ECJ. This was indeed the view expressed by both the president of the ECtHR and the president of the ECJ who, in another unusual public intervention, agreed to consider that "the reference for a preliminary ruling is normally not a legal remedy to be exhausted by the applicant before referring the matter" to the ECtHR. [20] Accordingly, Presidents Costa and Skouris suggested that a procedure be put in place to ensure that the Luxembourg Court may carry out an internal review before the Strasbourg Court carries out an external review of any EU act on fundamental rights grounds, with the important caveat that the ECJ should consider issuing rulings under an accelerated procedure so as not to prevent proceedings before the ECtHR being postponed unreasonably.

While some "dissenting voices" argued that no specific mechanism would be required if one were to compel national courts of last resort to refer any case to the ECJ in which it is alleged that a Union act is not compatible with the ECHR, much of the debate focused on what would be the best mechanism to guarantee a "prior involvement" of the ECJ. Space constraints preclude any critical assessment of these mechanisms but amongst the most significant proposals which have been made, one may mention the proposal to allow the ECtHR to refer a case back to the ECJ for a review of compatibility with the Convention [21] or the idea to entrust the European Commission to refer pending cases before the ECtHR to the ECJ so as to enable the ECJ to rule on the compatibility of the relevant litigious EU rules with fundamental rights standards prior to any intervention of the Strasbourg Court. [22] The crux of the matter was for the drafters of the accession agreement to devise a mechanism which would allow prior CJEU intervention where required without leading to lengthy delays in Strasbourg or placing excessive procedural burdens on the applicant. We shall see in Section 2 if this challenge has been met. Before doing so, one last highly contentious issue, which is directly linked to the question of prior involvement of the ECJ, needs to be explicated.

1.3.2 Identifying the correct respondent and the need for a co-respondent mechanism

In the absence of EU accession to the ECHR, the compatibility of EU acts with the ECHR cannot directly be challenged before the ECtHR for the simple reason that the EU is not (yet) a contracting party to the ECHR. In other words, it has hitherto been impossible for individuals to directly bring applications against the EU before the Strasbourg Court. This has not precluded difficulties arising in the situation where a private party seeks to challenge a national measure which implements EU law. This means that the ECtHR may find an EU Member State in breach of the ECHR although the EU Member State may have had no choice but to adopt the litigious national measure in order to implement relevant provisions of EU law. The EU Member State would then be left in a difficult position as it is both under an obligation to abide by the final judgment of the ECtHR (Article 46 ECHR) and an obligation to take any appropriate measure to ensure fulfilment of the obligations arising out of the EU Treaties or resulting from the acts of the EU institutions (Article 4(3) TFEU).

As EU law is applied in most cases to natural and legal persons via national measures, it has always been clear that a new mechanism allowing the Union and each Member State to appear jointly as "co-respondents" or "co-defendants" before the Strasbourg Court would need to be worked out. [23] The main objective was to ensure that the appropriate parties would be held accountable for any potential violations declared by the Strasbourg Court by enabling the EU to intervene as co-respondent in any case brought against a Member State before the ECtHR provided, of course, that the case raises an issue concerning EU law. By the same token, Member States had to be allowed to intervene as co-respondent in a case brought against the EU subject to the same conditions.

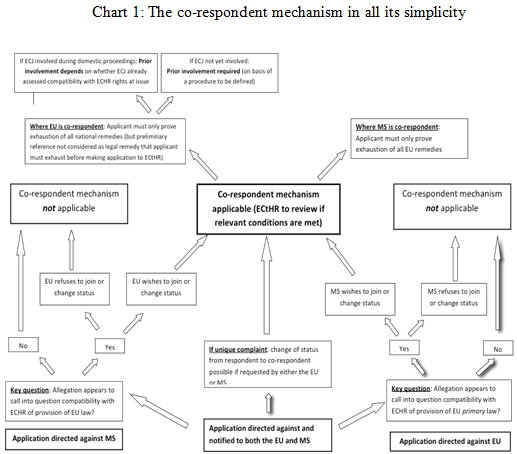

Multiple alternatives and perhaps overly sophisticated mechanisms have been suggested over the past few years. A popular idea consisted in allowing the European Commission or any EU Member State to ask for a reference from the ECJ in order to delineate the competences of the Union and its Member State and thus to determine who would be the appropriate respondent in any particular case. One of the obvious problems with this solution was that it would prolong an already lengthy process. More prosaically, some national governments such as Germany argued that it might be best to merely rely on a slightly revised third-party intervention mechanism already set out in Article 36 of the ECHR. This provision in particular enables any country to submit written comments and to take part in hearings in all cases before the Strasbourg Court whenever one of its nationals is an applicant, and also allows its President to invite any country to submit written comments or take part in hearings. During the drafting of the accession agreement, most stakeholders however pushed for the introduction of a completely new mechanism even though one should note that numerous NGOs have warned against any excessively complex mechanism and urged to limit as far as possible the use of any co-respondent mechanism. [24] There was furthermore ample debate on highly technical issues such as who should have the power to decide when a co-respondent be designated to proceedings and whether the applicant's consent must be sought before a co-respondent is joined to the proceedings. In fact, it was suggested that the Union should be obliged to join a case involving Union law as a co-respondent alongside the EU Member State but this proposal seemed to prejudge the liability of the Union. Another proposal was to allow the Union to seek leave to join as a co-respondent. Conversely, it may be contended that a co-respondent should only be joined to the proceedings at the request of the original respondent since it falls on him to assess the situation but this would give considerable power to the respondent and mean that the Strasbourg Court would not be in a position to object to any abusive use of this power. Generally speaking, however, most relevant stakeholders appeared to favour the introduction of a co-respondent mechanism in one form or another. According to the dominant view, such a mechanism would benefit applicants and help ensure the execution of the Strasbourg Court's judgments with the additional and important advantage of not compelling it to interfere in the division of competences between the EU and the Member States. We shall now review how the drafters have addressed the main points of contention highlighted above and in particular, whether they have been successful in devising a co-respondent mechanism that does not resemble a labyrinthine system.

2. The Answers Provided by the Draft Accession Agreement of 14th October 2011

2.1 Institutional Issues

Underlying the accession agreement is the aim of treating the EU as far as possible like any other High Contracting Party to the ECHR. The drafters only deviated from this premise where it was strictly necessary to accommodate the idiosyncrasies of the EU. As previously highlighted, the most contentious institutional issues revolved around the EU's participation in the bodies of the Council of Europe. Since it has always been clear that the EU is not going to become a party to the Council, specific rules had to be put in place for situations in which the Council's bodies are given responsibilities with regard to the ECHR. This is also reflected in the requirements set out in Article 1(a) of Protocol no. 8, which provides that the accession agreement must contain arrangements for the EU's participation in the Council of Europe's control bodies.

2.1.1 Mandate and selection of the EU judge

In compliance with the aim of guaranteeing EU accession on an equal footing with the other High Contracting Parties, the accession agreement does not provide for special rules regarding the future EU judge and reflects a clear rejection of all the suggestions made before and during the drafting process that the EU judge should have different terms of office. Rather, it leaves unaffected the "one party one judge" rule contained in Article 20 ECHR. In other words, the EU judge will not be treated differently to other judges on the ECtHR. This also implies that he will have to be elected by the PACE, a body composed of 318 MPs appointed by the national parliaments from the Council of Europe's 47 contracting parties. Since the EU will only sign up to the ECHR and will not become a party to the Council of Europe, it will not automatically be represented in the Parliamentary Assembly. For the election of judges, however, the draft accession agreement sensibly provides that the European Parliament will be represented by a delegation of MEPs with full voting rights, whose number equals the number of representatives sent to the PACE by the largest states (at present 18).

The selection process preceding the election of the EU judge will be the same as the selection process for other judges. The High Contracting Party concerned provides the Parliamentary Assembly with a list of three candidates for election. It is for the contracting party to define how the short-listing must be organised. However, the Parliamentary Assembly has issued recommendations as to how the selection should take place. Apart from criteria relating to the suitability of candidates for the position (legal qualification, etc.), the selection should follow a public and open call for candidates. Since the EU judge will most probably have the nationality of an EU Member State that fortunate Member State will have two of its nationals represented on the ECtHR. This may lead the Strasbourg Court to revise its internal procedures in order to avoid a situation where two judges of the same nationality sit on the same case brought against the High Contracting Party in respect of which these judges have been elected.

2.1.2 Participation of the EU in the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe

Concerns had been expressed with respect to the fact that the EU may lack any representation in the Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers, which is inter alia in charge of supervising the execution of judgments and friendly settlements, on the ground that the EU shall not become a party to the Council. However, the draft agreement offers a compromise solution whereby the EU is entitled to participate in the Committee of Ministers, with a right to vote, whenever the Committee takes decisions concerning the ECHR. The drafters were nevertheless fully aware that after accession, the EU and its Member States would command twenty-eight out of forty-eight votes in such matters, allowing them to block every decision if they so wished. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that under some circumstances the EU and its Member States are obliged to vote in concert due to the duty of loyalty contained in the EU Treaties (notably where the EU is either the main respondent or co-respondent). Since it is unlikely that the EU (and its Member States) would agree that it has failed to abide by a judgment, the supervisory mechanism would be unworkable in practice as far as the EU is concerned. In order to avoid such block voting, the accession agreement provides that the Committee of Ministers should adapt its rules of procedure to ensure that it "effectively exercises its functions" in the circumstances where the EU and its Member States express positions and vote in a coordinated manner (Article 7 of the draft accession agreement). It is likely that the new rules will provide that in such situations the Committee of Ministers can adopt a decision without a formal vote. This means that it will be sufficient that a majority of non-EU Member States have indicated to vote in favour of a measure concerning a decision in a case to which the EU was a party. Furthermore, it is provided in the draft agreement that the EU will not vote in cases where the Committee of Ministers supervises the fulfilment of obligations by one of the EU Member States.

2.1.3 EU Participation in the expenditure related to the ECHR

Whilst this issue never proved controversial and as such, was not previously discussed, it is nonetheless worth noting that the EU agreed to contribute to the expenditure relating to the entire Convention system and that its contribution is fixed at 34% of the highest contribution made in the previous year by any State to the budget of the Council of Europe. This would have meant for the EU the payment of a contribution of €9.34 million in 2011, [25] a drop in the ocean for the EU considering that its 2011 budget amounted to €141.9 billion.

2.2. Substantive Issues

2.2.1 Review of EU Primary Law

Contrary to the wishes of some EU Member States, the draft agreement does not exclude the review of EU primary law. To the contrary, the co-respondent mechanism (discussed below) presupposes such a review. Indeed, the EU Member States may only become co-respondents in situations where an application before the ECtHR calls into question the compatibility with the ECHR of a provision of the EU Treaties, i.e. EU primary law.

2.2.2 Future of the "Bosphorus Test"

The draft agreement is silent on the future of the Bosphorus test. This means that it has neither explicitly confirmed nor overruled the equivalent protection test, or clarified whether it should in fact be extended to all EU-related cases. It will therefore be for the Strasbourg Court to ultimately decide whether it should continue to apply a low standard of judicial review in situations where Member States adopt measures that merely implement legal obligations flowing from EU membership. As long as the EU offers a system of equivalent protection to that of the ECHR, the Strasbourg Court's default position is that the EU Member States have not departed from the requirements of the ECHR when they do no more than implement or apply EU law. The Court, however, will have also to decide whether the EU should benefit from a similar presumption of compatibility with respect to the measures it adopts. Considering that Bosphorus privileges the EU legal order by subjecting it to a lower level of scrutiny than the legal orders of its Member States, one may hope that the Strasbourg Court will do away with the Bosphorus approach as it cannot be reconciled with the overall and advertised aim of the draft agreement to treat the EU like any other party to the ECHR. [26] Indeed, we do not believe that a low standard of review is required to preserve "the specific legal order of the Union" (draft agreement's Preamble).

2.2.3 Accession to ECHR Protocols

The draft accession agreement provides that the EU accedes to the ECHR and Protocols No.1 and 6. In other words, the "minimalist" approach favoured by some EU national governments, whereby the EU should initially only be able to accede to protocols that were ratified by all its Member States, has prevailed. Regarding the remaining Protocols, the EU will have a chance to sign up to them at a later stage. For this purpose the EU would have to comply with the procedure envisaged by these Protocols and with the EU Treaties. The latter do not foresee a specific procedure for the ratification of Protocols to the ECHR.

2.2.4 Interpretative autonomy and exclusive jurisdiction of the ECJ [27]

Finally, we should briefly comment on whether the draft accession agreement affects the interpretative autonomy and the exclusive jurisdiction of the ECJ. It is recalled that no agreement may grant jurisdiction to another court but the ECJ to interpret EU law in a binding fashion. The accession agreement would not violate the interpretative autonomy of the Luxembourg Court in this respect. The Strasbourg Court would be restricted to a finding of whether a provision of EU law or an action or omission by the EU's institutions is incompatible with the Convention. Such a finding does not necessitate a binding interpretation of EU law provisions since the ECtHR would base its own findings on the interpretation previously rendered by the ECJ. Furthermore, the draft accession agreement does not give the ECtHR the power to declare provisions of EU law invalid. This power remains solely with the ECJ.

As regards the Luxembourg Court's exclusive jurisdiction, Article 5 of the draft accession agreement stipulates that proceedings before the ECJ do not constitute means of dispute settlement within the meaning of the ECHR. This removes the danger of EU Member States violating the ECHR where they are engaged in proceedings against each other before the ECJ even where such proceedings deal with ECHR provisions. The draft agreement therefore avoids a potential conflict between Article 55 ECHR and Article 344 TFEU, both of which would otherwise provide for an exclusive jurisdiction of the ECtHR and the ECJ respectively over such disputes. Thus Article 344 TFEU can operate without constraints and the monopoly of the ECJ to examine disputes between EU Member States is preserved.

2.3 Procedural Issues

The most intricate questions dealt with by the draft accession agreement are of a procedural nature. Two issues in particular proved contentious and technically challenging: the co-respondent mechanism and the procedure for a prior involvement of the ECJ. The ensuing analysis should help decide whether the House of Lords EU Select Committee was correct when they opined that while EU accession to the ECHR is likely to be politically and legally complex, "we do not doubt that, given the political will, the legal and other skills can be found to overcome the difficulties." [28]

2.3.1 Co-respondent mechanism

The co-respondent (or co-defendant) mechanism has been promoted to avoid an uneasy determination of the division of competences between the EU and its Member States when it comes to the implementation of EU law. It thus aims to comply with the EU Protocol no. 8, which requires that the accession agreement must include the necessary mechanisms to ensure that "proceedings by non-Member States and individual applications are correctly addressed to Member States and/or the Union as appropriate." Unsurprisingly, therefore, the application of the co-respondent mechanism described in the draft accession agreement is limited to situations involving the EU and its Member States, which means that the other parties to the Convention cannot avail of it. The draft distinguishes two situations in which the mechanism applies: the EU is co-respondent and one or more EU Member States are (main) respondents and one or more EU Member States are co-respondents and the EU is the (main) respondent.

Before going into the details of the co-respondent mechanism, it may be useful to distinguish it from two other traditional forms of involving more than one High Contracting Party in proceedings before the Strasbourg Court. As previously mentioned, third parties can get involved by way of a third party intervention which is laid down in Article 36 ECHR. As the name suggests, the involvement of the third party is triggered by its own application to the Court, but in contrast to a co-respondent, the intervener does not become a party to the proceedings and is thus not bound by the Court's decision. Another procedural difference lies in the fact that the ECtHR is obliged to make a party co-respondent where the conditions are fulfilled whereas the admission of an intervening party is in some circumstances within its discretion. Notwithstanding these differences, it is important to note that the draft accession agreement does not preclude the EU from participating in proceedings before the Strasbourg Court as a third party intervener where the conditions for becoming a co-respondent are not met.

The second way of involving more than one party is where the applicant nominates more than one respondent/State from the outset. Where this happens, both respondents must answer the case. However, this demands from the applicant that he exhausts the domestic remedies in all of the respondents' legal systems. By contrast, this is not required as far as the co-respondent is concerned. But the co-respondent mechanism cannot be applied where the applicant brings a case against the EU and one or more of its Member States alleging different violations. In such a case, all respondents must answer the case as ordinary respondents. Furthermore, a party can only become co-respondent at its own request and, unlike any "ordinary" respondent, is not obliged to answer the case. This means that it cannot be forced into that role. We will return to the issue of the voluntary nature of the mechanism once we have explained its mechanics.

i) The EU as co-respondent

Where one of the EU Member States is the respondent in proceedings brought by an individual, the EU may become a co-respondent "if it appears that [the alleged violation of the ECHR] calls into question the compatibility with the Convention rights at issue of a provision of European Union law, notably where that violation could have been avoided only by disregarding an obligation under European Union law" (Article 3(2) of the draft agreement). The situation envisaged by the drafters is one in which a Member State has implemented obligations contained either in EU primary law or in EU legislation following which litigation ensued before the relevant national courts with respect to the compatibility of the national measure implementing EU law with the ECHR. In such a situation the violation of the ECHR right(s) at issue has two possible sources: either the underlying provision of EU law was faulty, which automatically renders its implementation incompatible with the ECHR, or the legislation was compliant but was implemented in a way which was not in accordance with the ECHR.

The Member States are presently fully responsible for any violation of the ECHR in either case. [29] EU accession will not alter this situation but the co-respondent mechanism will finally enable the EU to join proceedings where it appears that its own law is not in compliance with the rights and guarantees set out in the ECHR. Where the EU decides to join proceedings in such a scenario, the advantage for the applicant is obvious: the judgment will bind both Member State and EU. This is most advantageous where EU legislation is at issue since the EU is the (only) entity capable of removing a violation by amending its own law.

Procedurally speaking, the decision of whether the EU may join proceedings as a co-respondent lies with the ECtHR, which, having heard the views of the parties must assess whether it is plausible that the conditions laid down in Article 3(2) of the draft agreement are met. At this stage of the procedure, the ECtHR is only expected to carry out a cursory examination of the EU's request. Only abusive or frivolous requests submitted by the EU – an unlikely scenario – would be rejected. However, in the situation where an applicant argued in his submissions that an EU measure violated the ECHR, the EU has a valid interest in becoming a co-respondent and defends the litigious provisions of EU law. Thanks to the cursory review of a request by the Strasbourg Court, which should make decisions simple, there is no great danger that the ECHR system will be clogged up with requests by the EU to be joined as a co-respondent. Furthermore, a decision would only be made after the ECtHR has concluded that an application was admissible. Since the vast majority of cases before the Strasbourg Court are dismissed as inadmissible, it is expected that decisions to join the EU as co-respondent will have to be made only in very rare occasions.

Finally, one should refer to an additional avenue whereby the EU may become co-respondent. In the situation where the EU is nominated as ordinary respondent alongside the Member State, that is, when an application is directed against and notified to both the EU and one or more of its Member States, the EU may still ask to be designated co-respondent provided that it makes an application to that effect. There seems to be no obvious advantages for the EU to make such a request unless the EU is convinced that the Strasbourg Court will eventually find the application, as far as it is directed against it, inadmissible on procedural grounds. This may appear counterintuitive but the EU might wish to avoid a situation in which the Member State would be left alone in defending a provision of EU law.

ii) The Member States as co-respondents

The conditions under which Member States can become co-respondents in the situation where the EU is the main respondent are closely modelled on those described above. In other words, the Member States must request the Court to either designate them as co-respondents or to change their status from respondent to co-respondent. Similarly to the EU, the Member States cannot be made co-respondents against their will.

Where the involvement of the Member States as co-respondents differs is as regards the substantive requirement. A Member State can only become a co-respondent where there is a question as to "the compatibility with the Convention rights at issue of a provision of the Treaty on European Union, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union or any other provision having the same legal value pursuant to those instruments, notably where that violation could have been avoided only by disregarding an obligation under those instruments" (Article 3(3) of the draft agreement). As a result, EU Member States can become co-respondents alongside the EU where a provision of EU primary law (e.g. a provision contained in the EU Treaties) is allegedly in breach of the ECHR. The reason for an involvement of the Member States as co-respondents is that only they – in their capacity as Masters of the EU Treaties – can remedy such a violation by way of a Treaty amendment, which requires ratification by each of the EU Member States in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements. The Member States' participation in such proceedings would therefore be of great advantage to the applicant since the EU alone would not be able to remedy the violation complained of.

iii) Assessment of the co-respondent mechanism

The co-respondent mechanism as such should be welcomed as a means of accommodating the specific situation of the EU as a non-state federal entity with a "specific legal order" (draft agreement's Preamble). To put it differently, while the functioning of the EU largely resembles that of a federal state, where the federation (EU) legislates and the states (Member States) implement such legislation, in contrast to other federations that are parties to the ECHR, the EU Member States are also parties to it with the result that the Strasbourg Court may face a unique situation in which the legislative (EU) and the executive (Member States) can be held responsible independently of each other. By contrast, the typical federal state is legally responsible for both federal action and state action. One may further mention the additional and peculiar problem of having a body of law, i.e. EU primary law, which can only be amended by the Member States acting unanimously as previously mentioned.

An additional advantage of the co-respondent mechanism is that it helps avoid a determination by the Strasbourg Court of who must be held responsible for a violation under the EU Treaties since both will be held responsible alongside one another in case of a conviction. However, we can identify one considerable weakness in the proposal, which is the decision to make it voluntary for the co-respondent to join proceedings. If a potential co-respondent decides not to join proceedings, the outcome of proceedings for a successful applicant are less satisfying as he cannot enforce the judgment against the potential co-respondent. It is clear that Member States will remain responsible for national measures rooted in EU law which may violate the Convention, and that the EU will remain responsible for its primary law so that an applicant will be able to secure conviction. But one must recall that the initial rationale underpinning the co-respondent mechanism was to account for the peculiar constitutional setup of the EU by enabling the ECtHR to find a violation without having to determine who was responsible for it. Under the draft accession agreement, it is within the co-respondent's discretion whether they want to become party to the proceedings. If a potential co-respondent decides not to join proceedings, the respondent will be responsible but cannot remove the violation.

Let us rely on the facts of the Bosphorus case to illustrate this point. Ireland had impounded an aircraft in accordance with its obligations under an EU Regulation. In any similar scenario, an applicant might bring a case against the relevant Member State claiming a violation of his property right under Article 1 of ECHR Protocol no. 1. Assuming that the violation was rooted in the EU Regulation and assuming that the EU refused to become co-respondent in the case, the Member State would be solely responsible for the violation in case of a conviction. But without the goodwill of the EU institutions to remove the violation by amending the litigious Regulation, the Member State would face conflicting obligations: on the one hand it would be bound by the Strasbourg Court's decision to release the aircraft and by its EU law obligation to impound it. This would appear counterproductive and can be considered a major shortcoming. It would have been preferable to enable the original respondent or the applicant to ask for a co-respondent to join proceedings. Especially in cases brought against the EU as the main respondent where the applicant alleges a violation contained in EU primary law, the situation may arise that only some of the Member States join as co-respondents even though, if a violation is found, they are responsible for it collectively. But this collective responsibility would not find an expression in the judgment. Moreover, the status of respondent in court proceedings is usually not voluntary so it is surprising that the co-respondent should have an opportunity not to opt into proceedings.

The question then remains what a strategically savvy applicant should do in order to avoid a situation in which the potential co-respondent does not join proceedings. As previously pointed out, from the applicant's point of view the major advantage of one party being a co-respondent is that the domestic remedies in the co-respondent's legal order need not be exhausted. But it is noteworthy that this advantage may prove to be of only limited practical relevance since in many cases there will be no such remedy in the first place. Indeed, the Treaty of Lisbon did not provide for a special remedy to challenge EU measures allegedly violating fundamental rights and did not include any radical revision of the law of legal standing for individuals in annulment actions, which makes it virtually impossible in practice for individuals to be granted the right to challenge the legality of a piece of general EU legislation in the EU General Court. Equally in situations where provisions of EU primary law are challenged, there is often no remedy available in the legal orders of the Member States. To conclude, there is no great risk therefore for an applicant in bringing a case against both EU and Member State as ordinary respondents from the outset in most cases.

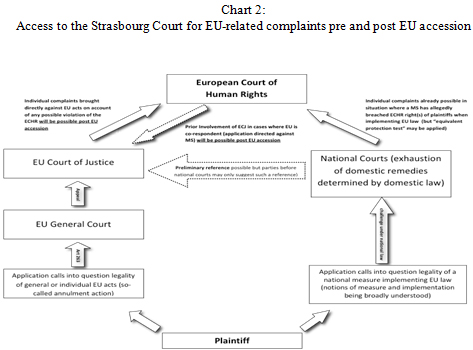

2.3.2 Exhaustion of domestic remedies and prior involvement of the ECJ

While EU accession to the ECHR will not modify the existing system of remedies under EU law, it will make it possible for natural and legal persons to directly challenge EU measures before the ECtHR if they consider that the EU has breached their rights under the ECHR [30] The usual admissibility requirements governing any application lodged with the ECtHR will nevertheless continue to apply, and in particular the condition pertaining to the exhaustion of domestic remedies. This means that an individual must first attempt to challenge the alleged violation in the courts of the party which is held responsible. In other words, where individuals wish to challenge the legality of EU measures directly with the EU institutions as respondents, the case will first have to be brought before the EU General Court which has jurisdiction, at first instance, over annulment actions brought by individuals. Following an eventual unsuccessful appeal before the ECJ, the dissatisfied party may want to bring a case before the Strasbourg Court on account of any possible violation of the rights and guarantees set out in the ECHR as one can see from the diagram below:

Whenever the applicant seeks to challenge a national measure that implements EU law, the situation becomes more complex. As shown in the diagram above, the applicant is only expected to exhaust the remedies in the legal order of the (main) respondent (i.e. the relevant Member State which adopted the litigious national measure) but not of the co-respondent (the EU). The drafters of the accession agreement were concerned with the situation where an applicant challenges a national measure implementing EU law before the national courts without any of these courts having referred the matter to the ECJ. Taking due note of the joint communication from Presidents Costa and Skouris of 24 January 2011 and in order to conform with the principle of subsidiarity underlying the ECHR system of judicial review, the drafters agreed that a reference to the ECJ for a preliminary ruling is not in itself a domestic remedy as under EU law applicants cannot force national courts to request such a ruling. The absence of a national reference to the ECJ must not therefore make any complaint before the ECtHR inadmissible for lack of exhaustion of domestic remedies. They furthermore considered it apposite to provide for a prior involvement of the ECJ in such cases where the ECJ "has not yet assessed the compatibility with the Convention rights at issue of provisions of European Union law" (Article 3(5) of the draft agreement) so as to guarantee that the Strasbourg Court does not rule on the compatibility of an EU act with provisions of the ECHR without the ECJ having had the opportunity to review the EU act on fundamental rights grounds.

This test, straightforward as it may sound, is prone to lead to difficulties. It may only be plainly satisfied where the ECJ has not spoken at all. Where the ECJ, however, has decided in a case following a reference by a Member State court, it would need to be decided whether the ECJ addressed the Convention rights at issue. There is no guarantee that this would happen in all situations since under the preliminary reference procedure the ECJ is normally limited to answering the questions submitted to its attention by the national court. An additional potential source of difficulty lies in the fact that the ECJ may decide a particular case on the sole basis of the EU's own human rights catalogue, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. It would then be necessary for the Strasbourg Court to determine whether the EU rights decided upon by the Luxembourg Court corresponded to the ECHR rights the applicant is invoking in its complaint against the EU as a co-respondent. The problem is that while the EU Charter does make clear that it contains rights which correspond to rights guaranteed by the ECHR, one must look at the EU Charter's official explanatory document to find a rather rudimentary list of the Charter's rights which are regarded as corresponding to rights in the ECHR (or its Protocols). One cannot therefore exclude that the Strasbourg Court might find it difficult to decide whether the ECJ had indeed already ruled on the compatibility of a provision of EU law with EU rights that correspond to ECHR rights. There is also the problem of EU Charter provisions that are based on rights set out in ECHR Protocols which the EU would have failed to accede to.

More intricate is the question of the mechanism to be used to organise a prior involvement of the ECJ in cases in which the EU is a co-respondent. This question remains hitherto unresolved since the drafters did not wish to interfere with the EU's procedural autonomy in determining how the ECJ should be involved. This position may be related to the concern that the ECJ may find the draft accession agreement not compatible with the EU Treaties on the grounds that it violates the autonomy of the EU's legal order or other conditions laid down in the EU Protocol no. 8 relating to Article 6(2) TEU. [31] The draft accession agreement does not therefore elaborate on how the ECJ should be involved. It merely obliges the EU to ensure that the Luxembourg Court makes its assessment quickly so that proceedings before the Strasbourg Court are not unduly delayed, which implies a forthcoming amendment of the ECJ's rules of procedure in order to give priority to such proceedings. A prior involvement may provoke additional procedural problems. No provisions are made in the draft and it falls on the EU to decide whether, for instance, the ECtHR must be allowed to make a preliminary reference to the ECJ as soon as the EU becomes party to a dispute before the Strasbourg Court or to entrust the European Commission with the task to ask the ECJ for a prior ruling in a similar situation. What is certain however is that the mechanism ultimately chosen must not confer new powers on the EU institutions including the ECJ which are not already provided for in the EU Treaties. Otherwise, the EU Treaties would have to be revised, which would be hardly desirable since it would almost inevitably lead to re-negotiations of other parts of the Treaties prompting a lengthy and unpredictable process. In the absence of a Treaty revision, the best option would probably be to entrust the European Commission, which would represent the EU before the ECtHR in such proceedings, to decide upon an involvement of the ECJ.

Lastly, some uncertainty remains with respect to the consequences of any ECJ decision finding the litigious EU act in breach of EU human rights standards in the context of the new prior involvement mechanism. The ECtHR would then have to consider whether it must continue with the complaint. It may be that in such a situation, the applicant should not be considered any longer a victim of a violation of the ECHR. Yet one must remember that in the present scenario, rulings by the national courts would be binding as res judicata and therefore would need to be removed (e.g. by reopening national procedures) before the Strasbourg Court should rightly come to the conclusion that the applicant is no longer a victim within the meaning of the ECHR.

2.4 Overall concluding assessment

In our opinion, the draft accession agreement manages to preserve the autonomy of EU law and it is obvious that its drafters took great pains to guarantee compliance with the requirements laid down in EU Protocol no. 8. Firstly, the accession agreement does not create new competences for the EU. Secondly, the co-respondent mechanism largely ensures that cases will be correctly directed either against the EU or its Member States. Finally, the autonomy of the EU's legal order and the ECJ's position as the ultimate guardian of EU law are preserved. However, the co-respondent mechanism is unnecessarily complex and one of its major shortcomings is that it is voluntary in nature. Furthermore, one may remain unconvinced with respect to the absolute need of providing for a prior involvement of the ECJ in situations where it had no opportunity to review the compatibility with the ECHR rights at issue of the provision of EU law. This leads to the ECJ being privileged in comparison with national constitutional courts of last resort, which do not always have the opportunity before applications are decided by the Strasbourg Court, to review the legal provision underlying the litigious action or omission complained of by the applicant. Furthermore, the prior involvement adds another layer of complexity to the already complicated co-respondent mechanism and may lead to considerable delays in proceedings before the ECtHR.

3. Next (procedural) steps and a health warning

In its report to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, the CCDH notes most delegations from EU and non-EU countries considered the draft accession agreement, in its current drafting, "as an acceptable and balanced compromise". [32] However, the European Commission indicated that there is a need for further discussion at EU level if only for the EU to decide on how to precisely organise the prior involvement of the ECJ and implement the co-respondent mechanism. Indeed, these are purely EU internal matters but of crucial importance and it may take time before consensual solutions are worked out between the different EU actors. In any event, the draft accession instruments have now been forwarded to the Committee of Ministers for consideration and further guidance. Because a number of EU Member States continue to have a number of reservations regarding the mechanics of the co-respondent mechanism, one cannot completely exclude further revision of the draft accession agreement of 14th October 2011.

Provided that the Committee of Ministers adopts the accession agreement, its entry into force must overcome a certain number of obstacles. Firstly, the 47 state parties to the ECHR and the EU will have to sign it. The EU will then have the option of making reservations to the ECHR to the extent that EU law as it stands on the day of the signing of the agreement is not in conformity with any particular provision of the ECHR. With respect to the ratification of the agreement, one must distinguish between national ratifications by the states parties to the ECHR and EU ratification. As regards the EU, Article 218 TFEU provides for a special ratification regime for a number of specific international agreements, including any agreement on EU accession to the ECHR. In other words, the Council of the EU will have to unanimously agree to adopt the decision concluding the agreement after having obtained the consent of the European Parliament. The decision of the Council of the EU concluding the accession agreement will then have to be approved by each EU Member State in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements. Last but not least, the agreement will also have to be approved by all 47 existing contracting parties to the ECHR, including the 27 EU Member States in their capacity as parties to the ECHR, in accordance once again with their respective national constitutional requirements. Numerous procedural hurdles will need therefore to be overcome before the accession agreement enters into force. Were the ECJ to be asked as to whether the envisaged accession agreement is compatible with the EU Treaties – and this looks more likely by the day – we might be in for a nasty surprise although this would seem unlikely considering that the drafters of the accession agreement took great pains to comply with the views of the ECJ as expressed in a number of public documents.

One may be forgiven for thinking that we have spent enough time already debating the merits of EU accession to the ECHR and working out the technical details this would entail. While a lot of ink has been spilled on issues such as the co-respondent mechanism, it would seem that only three cases would have certainly required until now the application of this mechanism. [33] It is unlikely also that many successful applications will be brought against judgments of the ECJ in the context of direct actions whenever the ECJ will refuse to find a violation of human rights in the case at hand. It may be worth recalling, in passing, that 96 per cent of all applications submitted to the Strasbourg Court during the period 1959-2009 were declared inadmissible. It may very well be that EU accession to the ECHR will decisively "enhance coherence in human rights protection in Europe" (Preamble to the draft agreement) but one must not forget that the EU is about to join a system in deep crisis and "in danger of asphyxiation" [34] as it struggles with approximately 139,650 pending applications on 1st January 2011. To make matters worse, some have predicted that the ECJ would also soon face another crisis of workload. [35] It is hoped therefore that with the question of EU accession to the ECHR soon out of the way after more than fifty years of debate, ECHR and EU authorities will refocus their energy on finding radical and durable solutions so that the ECtHR and the ECJ can cope with their new tasks and ever increasing workload.

[1] For a general overview of the impact of the Lisbon Treaty on fundamental rights protection in the EU, see our previous policy paper no. 173, 14 June 2010: http://www.robert-schuman.eu/question_europe.php?num=qe-173.

[2] For a thorough historical overview and further references, see J.-P. Jacqué, "The Accession of the European Union to the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms" (2011) 48 Common Market Law Review 995.

[3] See in particular the European Commission's memorandum of 4 April 1979, Supplement no. 2/79, Bulletin of the EC and the communication it published on 19 November 1990 (Sec(90)2087 final).

[4] See Opinion no. 2/94

[1996] ECR I-1759.

[5] The ECJ is based in Luxembourg while the ECtHR is based in Strasbourg.

[6] The European Convention, Final Report of Working Group II, Conv 354/02, 22 October 2002, p. 12.

[7] Article 59(2) of the ECHR as amended by Protocol no. 14 makes provision for a non-state entity, the EU, to accede to the ECHR.

[8] A partially declassified version of the Council decision authorising the Commission to negotiate the accession agreement has since been made available but the Council's negotiating directives remain secret.

[9] The website of the Council of Europe's Informal group on EU accession to the ECHR (CDDH-EU) offers easy access to the draft legal instruments and other informative documents: http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/hrpolicy/CDDH-UE/CDDH-UE_documents_en.asp.

[10] Report of the CDDH to the Committee of Ministers on the elaboration of the legal instruments for the accession of the EU to the ECHR, CDDH(2011)009, 14 October 2011. The report reproduces in an appendix the most recent version of the draft legal instruments.

[11] See consolidated versions of the EU Treaties

[2010] OJ C 83/273.

[12] For further references, see recently see T. Lock, "Walking on a tightrope: The draft ECHR accession agreement and the autonomy of the EU legal order" (2011) 48 Common Market Law Review 1025.

[13] Provided that the ECJ had indeed jurisdiction over the relevant EU acts.

[14] See recently Sejdic and Finci v. Bosnia, nos. 27996/06 and 34836/06, 22 Dec. 2009.

[15] Matthews v. UK, no. 24833/94, 18 Feb. 1999.

[16] See in particular Bosphorus Airways v. Ireland, no. 45036/98, 30 June 2005.

[17] See e.g. Opinion no. 1/91

[1991] ECR I-6079 where the ECJ held that the EU had no competence to enter into an international agreement that would permit a court other than the ECJ to decide on the allocation of powers between the EU and its Member States or make binding determinations about the interpretation or validity of EU Law.

[18] Document available at: http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/P_64268/

[19] Article 35(1) of the ECHR provides that the ECtHR may only deal with an application alleging a violation of the rights and guarantees set out in the ECHR after all domestic remedies have been exhausted and within a period of six months from the date on which the final decision was taken.

[20] The joint communication from Presidents Costa (ECtHR) and Skouris (ECJ) published on 24 January 2011 is available at: http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/P_64268/

[21] See e.g. Communication no. E 5248 de M. Robert Badinter, Sénat, 25 May 2010, p. 7.

[22] See presentation by ECJ Judge Timmermans at the hearing organised by the European Parliament's Committee on Constitutional Affairs, 18 March 2010.

[23] See e.g. Council of Europe, CDDH Study of Technical and Legal Issues of a possible EC/EU accession to the ECHR, DG-II(2002)006, 28 June 2002, paras 57-62.

[24] See e.g. the note addressed to the CCDH-EU informal working group by Human Rights Watch et al., NGOS's Perspective on the EU Accession to the ECHR: The Proposed Co-respondent procedure and consultation with civil society, 3 December 2010.

[25] See para. 85 of the draft explanatory report relating to the draft accession agreement.

[26] See para. 7 of the draft explanatory report: "The current control mechanism of the Convention should, as far as possible, be preserved and applied to the EU in the same way as to other High Contracting Parties, by making only those adaptations that are strictly necessary."

[27] Strictly speaking, the draft agreement refers to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), which is the name given to the whole court system of the EU post Lisbon Treaty and which comprises three courts: the Court of Justice (commonly known as the ECJ), the General Court and the Civil Service Tribunal. For simplicity's sake and because, in the context of the accession agreement, the term CJEU always means in practice the ECJ, we decided against using the term CJEU.

[28] 8th Report on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, 16 May 2000, para. 142.

[29] As previously explained, the Strasbourg Court does not currently review national measures that implement EU law as long as the EU is considered to protect fundamental rights in a manner which can be considered at least comparable to that for which the ECHR provides.

[30] Strictly speaking, the EU will be responsible for all acts, actions or omissions of its organs.

[31] Article 218(11) TFEU provides that "A Member State, the European Parliament, the Council or the Commission may obtain the opinion of the Court of Justice as to whether an agreement envisaged is compatible with the Treaties. Where the opinion of the Court is adverse, the agreement envisaged may not enter into force unless it is amended or the Treaties are revised."

[32] CDDH Report (2001) 009, 14th October 2011, para. 9. Some influential EU Member States, however, are still unhappy with some fundamental aspects of the draft accession agreement. See e.g. the UK non-paper submitted to the Council of the EU (working party on fundamental rights), DS1563/11, Brussels, 22nd September 2011.

[33] Explanatory report, para. 44, fn. 18.

[34] Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, PACE, The future of the Strasbourg Court and enforcement of ECHR standards (Conclusions of the Chairperson, Mrs Herta Däubler-Gmelin, AS/Jur (2010) 06, para. 9.

[35] UK House of Lords EU Committee, The Workload of the CJEU, 14th Report of Session 2010-11, 6th April 2011 (this report offers an even bleaker prognosis in relation to the EU General Court).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :