Economic and Monetary Union

Alain Fabre

-

Available versions :

EN

Alain Fabre

Economist and historian

The euro crisis has led to greater awareness on the part of governments and public opinion of the close, direct link that exists between an integration of monetary policy to be achieved legally and operationally via the euro and the unsettling diffuse nature of national budgetary policies that have remained totally autonomous. The Stability and Growth Pact that was based on a series of autonomous, national solutions has failed. The danger of bankruptcy on the part of some States that threatened the continuity of the entire euro area led to the introduction of a European Financial Stability Fund of 750 billion €; this may become a permanent fixture in terms of European financial and monetary integration. Hence the crisis has revealed the fundamental logic behind Monetary Union: the euro demands financial solidarity between States, which in turn calls for the integration of national policies [1] according to a German budgetary stability model [2].

The crisis has therefore revealed all of the components that point to the logic of community supervision of economic policies. From now on via the joint guiding principle of their economic policies European governments intend to address issues of competitiveness and imbalance in the EU between the various States without losing sight of its position in the world economy.

Attention is now being drawn to thought about the long term effects of national policy hence their importance in the consideration of all competition related issues, as shown in the preparatory work undertaken with regard to the Pact for the euro passed in Brussels on March 11th.

The potentially disruptive effects of national fiscal policy on the mobility of factors of production within the Union are a particular target. Some national economic policies are sometimes criticised by those who believe them to be an attempt to achieve unilateral advantage by applying significantly reduced tax rates to the most mobile factors of production, skilled labour and capital implying both financial movements and the relocation of companies. Prior to crisis the autonomy of national policies in the open economy and monetary zone heightened the temptation to employ a certain type of "fiscal competition" between States.

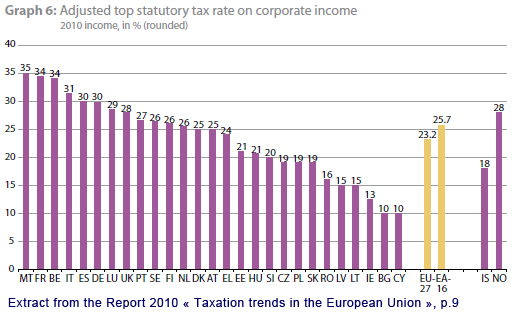

The example of Ireland and its business tax of 19% has often been quoted to illustrate the policy of a euro zone Member State which attempted to attract activities established in neighbouring States at the expense of greater public financial exposure – its partners stood fast however as the last resort preventing the bankruptcy of the State and the banking system. Beyond the euro area debate revealed further divergence since the new States that joined the EU in 2004 often employed "flat tax", i.e. uniform, reduced rates whatever the fiscal base which required intervention on the part of the IMF in Romania during the crisis of 2008-2009.

However the question raised by States that support reduced taxes and objections over the true meaning of fiscal harmonisation – notably embodied by the UK, is not totally injudicious because of the overall weight of public and social spending in Europe in view of the demands of international competitiveness and the danger of any resulting public financial debt. As a whole the Union is emerging from the crisis and now faces the dual need to reduce its debt and deficits and to seek the right conditions to foster significant improvement in its growth potential. In an open economy which is exposed to increased world competitive pressure the EU will only succeed in finding an effective fiscal strategy – i.e. that fosters its competitiveness as a whole and which reduces the potentially disruptive effects of excessive variations in tax rates, by committing to determined, energetic action to reduce public and social spending. Concerned about the intrinsic decline in both its absolute and relative growth in comparison with that of the USA or the emerging countries, the EU cannot afford not to reflect on the burden of its spending and its social and public levies and the decline of its growth rate. Again an organised European strategy is vital – there could be nothing worse than individual responses.

A fiscal strategy that is necessary for a Europe committed to world competition and the stability of the Member States' economies.

A community fiscal strategy is necessary both to prevent potentially disruptive events due to an excessive range of tax rates amongst the Member States and also to foster European competitiveness with regard to other major regions in the world.

The effects of the opening of economies on fiscal policy

Here we should just remind ourselves of the basic elements of how the tax system works in an open economy. [3] [4]

In virtue of the Ramsey theory, in order to reduce losses in efficacy associated with any levy, the tax system must apply to relatively inflexible bases, i.e. which are not sensitive to an increase in contributions [5]. In this sense the ideal tax system is one which is built on a wide base and low rates. A. Laffer demonstrated that a continuous rise in marginal tax rates tended, all things equal, to reduce tax revenue.

The optimal tax system is that which applies to everyone and in which marginal degressive tax rates are applied to enable a positive marginal utility of labour. Finally the entity which finally pays the tax is not necessarily the one to whom it applies. It always finally tends to weigh on the least mobile, least elastic bases.

The opening of the economies reveals a major differentiation in fiscal bases depending on their degree of mobility. It brings into play a multiple number of forces that are potentially incompatible. Depending on the mobility potential of the various factors of production opening firstly affects the tax system in its primary function i.e. the collation of public resources and all things equal, the States' levels of deficit and debt. It exercises pressure on the redistributive capacity of public policy: the ability to avoid tax by the most mobile factors reduces the redistributive capacity of revenue after tax. It leads to variation in the degree of competitiveness of the productive system in terms of external competition. It modifies the relative attractiveness of a State with regard to its partners.

In order to assess what really is at stake in terms of the effects of the opening of economies on fiscal policy it must be stressed that generally the most mobile elements are also those which contribute most to the system, employees are the most highly qualified and companies are best positioned in terms of international trade. As an illustration we might point to the focus on income tax in France where 20% of tax payers ensure the payment of 90% of the total. Likewise we recall the weight of social contributions paid by companies which affects the cost of labour in production decisions in a State with a given productivity of labour. Finally in order to appreciate the choices made within the EU we should remember that the 27 Member States find themselves before opening which is twofold: internally and externally.

Heavy taxation in Europe as a whole, but which are disparate from a national point of view.

The effect of this dual opening, both internal and external, of European economies is leading to a generally high taxation rate in Europe. But the striking thing within the Union is a major and ever increasing variety of levies applied to capital and labour, but which is quite low on consumption.

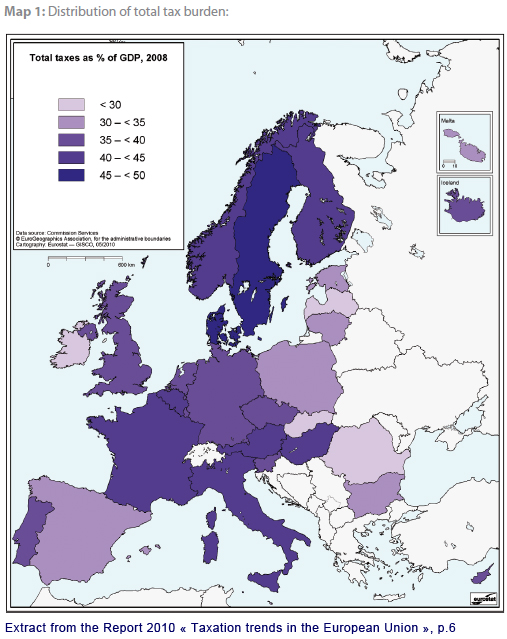

According to Eurostat data [6], the European Union is a high tax zone with obligatory levies representing 39.3% of the GDP in 2008. This is a third more in comparison with the same data recorded for the USA and Japan. However since the start of the noughties the level of obligatory levies has declined slightly in Europe. However following those years which were rather more marked by a downward trend in activity there is now an upward trend that goes hand in hand with a rise in contribution levels, but in which taxation rates have hardly changed. Hence in support of increasing growth contribution levels totalled 41% on average in the present 17 euro area countries. In 2008 this figure dropped down to 39.7%, close to the rates seen in 1995.

The most striking factor is still the variety of taxation rates whichever environment is considered; in the EU, if we look at 2008 data the difference is extremely significant between Denmark, (48.2%) and Romania (28%). Within the euro zone, the situation is similar between Ireland where levels lie at 29.3% of the GDP and Belgium where levels reach 44% of the GDP. Even between the "big" countries we can see a similar trend. In Germany, contribution levels rose to nearly 42% in 2000 decreasing to 39.3% in 2008. In France levels dropped from 44% to nearly 43%. Hence between the two lead countries in the euro area there was a difference of 2 points in 2000 and in 2008 this totalled 3.2.

The variety of fiscal pressure in the wider sense of the term particularly involves revenues on labour and to a lesser degree on capital. However it is weak in terms of taxation on consumption.

Consumption has the dual specificity in that it is not very mobile and for this reason is subject to European harmonisation even though community rules set a minimum and not a maximum. The choice of a VAT rate is not linked to tax rates as a whole. Poland and Ireland employ high VAT rates whilst overall fiscal pressure is low.

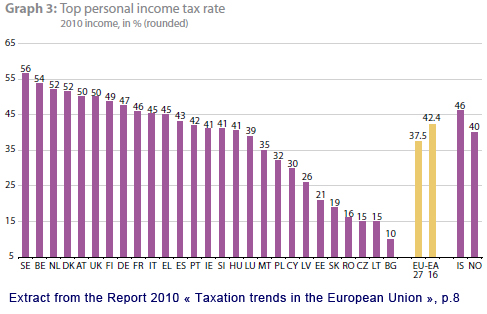

Generally and logically the 27 Member States rather tend to tax labour because it is less mobile than capital and because of the major role played by social spending. This trend is attenuated by the desire not to penalise low skilled labour – which in turn is an incentive to reduce social contributions on low wages. The discomfort on the part of some States can be seen with regard to highly skilled labour which is both a net contributor to the redistribution system and at the same time is highly mobile within the Union and even beyond.

The goal pinpointed by the governments of Europe to re-balance relative taxation on capital and labour, the desire no longer to focus on social levies based on labour alone and therefore to achieve an increased taxation on capital is challenged by a high degree of mobility, which incidentally is one of the founding elements of the European treaties. In these circumstances the lack of flexibility in terms of taxing the most mobile taxable bases - skilled labour and capital – and the refusal to penalise unskilled labour finally leads to the taxation of consumption. The most representative example of this is Germany which compensated for a reduction in social contributions by an increase in VAT.

But overall it is the significant weight of public spending in % of the GDP in Europe which explains the lack of flexibility and the difficulties experienced in achieving a unanimous approach to fiscal strategy in the Union. This runs alongside the observation we can make about levies: there is high pressure in Europe in comparison with the rest of the world and a high degree of disparity. Action towards reduced fiscal divergence in Europe goes together with a programme for a thorough reduction in public and social spending in % of the GDP. This work undertaken in all European economies would comprise one of the best ways to reduce variations in national situations.

Although the crisis led to a rise in the weight of public spending in % of the GDP in 2008 to a level of 51%, either in terms of the euro area or the EU average – notably because of the contraction in the GDPs and the acceptance of automatic stabilisers, the situation is peculiar if we compare it with countries such as the USA where public spending totals around 35% of the GDP in periods of growth and 39% in times of crisis. In times of growth the European average lies at around 47%. Hence there is a structural difference of around 11 to 12 GDP points. If Europeans devoted the same proportions to public spending as the USA around 1,300 billion € would return to the European productive sector!

The role granted to the Welfare State within the economy and society is at the core of implicit fiscal divergence between European States. Within the euro area the variation in situations is extremely high. Before the crisis [7], Ireland devoted 37% of its GDP to public spending, France 53%, Denmark and Sweden 51%, Italy 48%, the UK 44%, Germany 43%, Spain 39% and on average the rate lay at 47% in the EU. Again we should highlight the policy implemented by Germany in terms of reducing the weight of public spending by 4.7 points of the GDP from 2003-2007. Europe's leading economy has therefore demonstrated that it is quite possible to reduce public and social spending without compromising its population's living standards. Hence in 2008 when activity was contracting Germany was practically on a par with France in a time of growth. In 2008 France devoted 56% of its GDP to public and social spending i.e. 160 billion € more than Germany (47.5%).

Finally the crisis led the States into public deficit and debt which was untenable long term. Governments have had to reduce the latter drastically whilst growth remains feeble [8].

Hence Europeans accumulate all types of impediment in terms of finding a strategy for national public levies that is compatible with their partners: a concurrently excessive level of spending, levies, deficits, debts, together with a surfeit of national situations. However because of the crisis which notably increased a feeling of public financial vulnerability in many places (Spain, Portugal, Greece, the increase in interest margins demanded by the markets), the States with the heaviest fiscal situations have become aware of the potentially disruptive and self-fulfilling nature of raising marginal tax rates whilst their partners, because of a less comprehensive Welfare State or because their public financial situations were better found themselves in a position that enhanced their relative attractiveness.

The Fundamental Elements of a Community Fiscal Strategy

The asymetrical disruption resulting from this type of situation within the EU could depress national economic growth mid-term. This would only increase the divergence between economies witnessed during the previous decade. The effects would be all the more disruptive if they weighed on policies implemented for the stabilisation of public deficits.

Teasing out the conflict between harmonisation and unilateralism

In order to set down a fiscal strategy that will lead to a rise in growth potential across the entire EU and to increased convergence of public finances, it seems vital to achieve a common vision on fundamental goals and methods. By this we mean that leaders must find an intelligent compromise between harmonisation – which is the source of hope for some and for others the fear of standardisation and the loss of any form of freedom to act – and the status quo which is an incentive to seek unilateral advantage. Both of these mask protectionist ulterior motives – the EU must draw up a tenet that will really lead to the mobility of labour and capital without falling into the trap of re-routing activity which would be contrary to the Treaty. This requirement is all the more vital since the Founding Fathers shared similar social ideals whilst this consensus no longer exists. The States that entered the EU between 2004 and 2007 mainly fear, in the name of social ideals of their forefathers, a restoration of measures that are both protectionist and damaging to the work they have undertaken increase growth and to catch up on living standards in the western part of the Union.

Agreement on goals means primarily coming to a minimum joint vision in Europe on the fundamental principles governing State intervention in the social market economy, which is the type of economy accepted by the treaty; this particularly involves the role of the Welfare State. The issue is significant because apart from policies drawn up in terms of efficacy Union citizens have the right to expect their leaders and the community institutions put forward a European ideal of civilisation. Work that tries to reveal the things that unite Europeans can but facilitate the way we are to express the diverse nature of our economies and societies. This does not mean launching into projects that have no operational goal. Nor is it a question of trying to erase the diversity of national policy and economy, particularly with regard to setting limits that would affect the development strategies of the EU's most recent members. It is rather more a question of providing more substance to vital elements of the social market economy model and to a certain extent of being able to draw up a strategy for European civilisation in which competitiveness complements the goals of social policy.

Transposed in terms of economic choice in the Union this means that different productivity conditions in Denmark and in Slovenia require responses that are adapted to local situations. The EU has to start by challenging two opposite trends. Firstly calls for harmonisation should not become a pretext - in the guise of a discourse that is generous on the surface – but which in reality aims to reduce the growth potential of some via restrictions set by others. Hence France is sometimes suspected – quite justifiably – of wanting to force social standards on its partners to compensate for its lack of competitiveness. The French social model is not what Europe is aspiring to.

Conversely to during the crisis, which seemed to favour a return to a common sense approach – not only did the use of fiscal policy to achieve unilateral advantage, and which aimed artificially to stimulate growth prove to be disruptive but it was above all counterproductive for the EU including from a national point of view.

Generally we should remember that from a macro-economic point of view it is not contrary to the Union's monetary rules to maintain a natural autonomy in terms of fiscal policy. Different choices of society from one State to another are not contrary to the ideal of European integration. On the contrary one of its aims is to remain sufficiently strong in order to maintain the diversity of social choice from one State to another. It is because of the effects on the Union and on its partners that a State's freedom of political action cannot be dissociated from its responsibility. Hence it is legitimate to allow States the freedom to choose a fiscal policy that is adapted to differences in productivity from one region to another. To go against this in the name of a badly understood ideal of union would only do a disservice to European integration.

To address these sensitive issues we must bear in mind the fundamental base at our disposal, notably the frequently quoted example of the USA. With regard to the latter there are three factors which distinguish the American situation from that in Europe.

Firstly the labour market is totally flexible in the USA both in terms of price and access by workers from one State to another. In Europe labour markets are still subject to national structuring. Hence contrary to the USA we do not see Spanish workers migrating to Germany when unemployment increases in Barcelona and decreases in Munich. Here we recall the emblematic episode of the Bolkestein directive on the liberalisation of services.

Moreover because of its size the American federal budget (around 20% of the GDP against 1.3% in the EU) has a powerful effect on the entire economy and aids savings transfers from one area to another. We might add that in the event of financial difficulty federated States such as California become an agent of common law (financial restructuring procedures etc ...); this is not the case in a State of sovereign rule such as Spain, Portugal or Greece.

Finally another decisive factor is the USA's capability to drain – almost infinitely – the world's savings and its discretionary use of the dollar in settling internal domestic financial matters. These are the tools that Europeans do not have either together or individually.

The Virtuous Circle of Cooperative Strategies: the Opportunity to use the Dynamic of Public Deficit Reduction Policies.

Together these three differences oblige Europeans to draw up cooperative strategies – but how should they go about this?

The first thing to consider is that the solutions selected in terms of VAT harmonisation are not necessarily applicable everywhere. They apply to household consumption with low mobility. They aim to make national rules compatible amongst themselves so that they do not restore obstacles to trade.

The second is to consider that concerted action must be applied to the most mobile factors of production - capital and highly skilled labour. This does not imply the prevention or reduction of mobility; we have to ensure that it is governed by basic economic and not artificial considerations based on fiscal arbitrage. The most recalcitrant States with regard to relaxing their taxes have to believe that in an open economy and exterior to any cooperative approach, mobility exercises a decreasing effect on marginal tax rates in any case and places the governments in question before an embarrassing choice of either accepting an increase in their deficits because part of the taxable base has disappeared or to increase the taxes of those who are the least mobile. But we know that long term it is the least mobile tax payers who compensate for the disappearance of those who are highly mobile.

Finally European leaders' work must be based on a general orientation of economic policies towards reducing deficits. From this point of view an effective way of reducing differences in opinion is to focus on cutting expenditure rather than on increasing contributions which are already high and almost unbearable in many of the Union's Member States. The French government, which is aiming to bring its tax system in line with that of Germany will only be able to provide substance to its claims if public spending declines drastically in % of the GDP. The report just published by the Financial Court in France [9], recalls that the recovery of French competitiveness cannot simply be attributed to the differences in tax structure on either side of the Rhine. Competitiveness is based on fundamental elements of the economy. Jean-Marc Vittori points to the obvious contradiction in the French discourse on this matter recalling that the main difference between France and Germany was not so much a question of taxation but public spending. We might quote Sweden which reduced public spending by 20% over 15 years without "falling into the abyss" [10]

To avoid being locked into a vicious, contradictory circle which all proponents of inertia would call upon there are ways which are progressively emerging from the plethora of thought either on a community, government or university level.

The tax regime governing the most mobile factors of production in the Union, a priority goal for a common strategy

Three priority areas comprise the most mobile factors of production: company tax, notably that of groups, income tax on the most skilled employees, and levies on capital.

On this matter the first idea would be to bring European taxation systems towards using wide bases and reduced rates. France has a tax policy which relies greatly on narrow bases and marginally high rates. A reform such as that undertaken to the CSG since 1988 would provide a welcome contribution to modernising fiscal policy and towards European convergence.

Generally speaking work leading to a European definition of taxable bases is a move in the right direction. The Pact for the euro passed on 11th March by the euro area members is due to implement a common tax basis for business tax. The Commission is in charge of proposing a draft on this matter on 16th March.

The second idea would be to pinpoint community goals that target the model of the old European Monetary System (EMS). This would mean defining the admissible range of rates, possibly based on weighted averages notably according to absolute GDPs or per capita. If Denmark and Sweden reduced income tax suddenly there would be greater effect on Spanish or French executives than if the same solution was adopted by Slovenia and Malta. Hence a State would not be able to apply company tax rates that diverged (upwards or downward) by more than x points set on a community level.

The third idea would be to introduce more restrictive criteria, not with regard to rates but in terms of effective application, within the 17 euro area Member States rather than in States which do not belong to the zone. A State cannot share the same currency with its partners and take significant budgetary risks involving intentional reductions in its taxes.

Although the implementation of this type of solution may seem technocratic at first, it would be necessary to establish sensitivity indicators with regard to fiscal policy Europe wide. What effect for example would a reduction in company tax or a dispensation from capital tax have on public finances both short and mid-term on a State? In Ireland for example the reduction in company tax which not did just aim to but also achieved vigorous growth did not prevent the State from finding itself in a situation of aggravated vulnerability. It is clear that such mechanisms would be applied more to control or aid policies to reduce rather than raise taxes. With regard to these issues it does not seem illegitimate for the Commission or the Presidency of the Union to undertake an information campaign in the States which are "addicted" to tax the external effects of which we would be wrong to ignore. Tax havens exist because there is tax hell.

Finally it is important to establish a European tenet common to all States i.e. the stability of fiscal rules within the 27 EU Member States. The comparative situation between France and Germany also depends on the difference in the long term nature of fiscal rules between the two countries. For example all 27 Member States might be encouraged to accept a non-retroactive principle applicable to fiscal rules. A great number of the wealthy choose to be governed by a State's tax system not so much because of the tax rate but rather because fiscal rules on the basis of which major decisions have been taken might be called into question.

The success of the German and Danish policy to transfer social contributions over to VAT has been thought provoking for a number of States. Generally States are torn between their attachment to high social protection, their desire to enhance competitiveness and their determination not be penalised by States that are not as socially innovative or which are like the States of Central and Eastern Europe i.e. mostly concerned by their successful transition over to western living standards.

From this point of view it is not so much the mobility of labour that is a risk but rather the transfer of activity from one Member State to another. This is more of a problem for labour intensive industrial activities. It is an area in which the subsidiarity principle applies and in which the interaction of comparative advantage does not need to be radically changed as part of the market economy model which serves as a foundation to the Union. One way of raising community awareness probably comprises questioning the EU's competitiveness as a whole, with regard to the rest of the world. This is one reason why governments should be encouraged to share their ideas about using VAT to fund the European Welfare State. Because by definition it is a tax that influences goods imported into Europe from the beginning; it facilitates the introduction of sustainable strategies to enhance the competitiveness of European production. From this standpoint it is likely that many leaders who want to maintain their level of social protection and yet seek improvements in the competitiveness of their companies will be persuaded to transfer the burden of labour contributions over to VAT.

In the wake of the financial turbulence that shook the euro area in 2009-2010 Europeans have been forced to rethink their growth strategy in terms of competitiveness and no longer in terms of macro-economic stimulation. They face the triple challenge of their overall competitiveness vis-à-vis the rest of the world, the influence of reciprocal interdependence - since the States undertake more than half of their trade within the Union - and risks associated to a trend towards the dispersal of performance and fiscal situations that were taken by surprise by the financial and banking crisis.

The interlinking of all of these factors is necessarily leading to greater awareness which is contributing to a process – albeit a laborious one – but the sense of which is quite clear. The tenacity of Herman Van Rompuy deserves our respect since it is a political exploit to bring governments together of such disparate sensibilities and who always think they have to make nationalist pledges to their public opinion.

At a time when China is rising to become the world's second economic power we should remember that the European Union occupies this position on the podium at present. It is therefore time to create the tools for an economic policy to wake Europe up, which far from making the world tremble should on the contrary help towards its serenity. As Laurent Cohen-Tanugi says "time is short and we can no longer afford to waste it on impotent realism that has held Europe back for years – the time has come for liberating audacity [11]"

[1] And not just coordination inspired by Keynesian models in which the States in relatively favourable financial positions with regard to the others would stimulate demand, the States in a relatively unfavourable situation would adopt conversely restrictive budgetary policy.

[2] Which does not mean, contrary to popular belief, a simple alignment on the German budgetary policy. This type of budgetary policy leads to an acceptance of long term control of deficits and the relinquishment of expansive long term policies. It does not create any real loss of autonomy. It is perfectly compatible with an autonomous use of deficit in times of economic lows and it is all the more effective since it suppose a controlled public financial situation at the end of an upward trend. It leaves great macro-economic autonomy in terms of levels and structures of levies.

[3] Here the term tax system is assimilated with that of obligatory levy thereby incorporating local and social taxes.

[4] Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Martine Carré-Tallon, Matthieu Crozet Une fiscalité compétitive dans un monde concurrentiel, Report for the Obligatory Levies Council CEPII, October 2009

[5] Example of the domestic tax on oil products in France (TIPP).

[6] Eurostat Taxation trends in the European Union Main results 2010 Edition

[7] Eurostat Data 2007

[8] Cf. Alain Fabre, "The Euro Area in the Autumn of 2010 : Economic Policies on a Razor Edge?" European Issue, Robert Schuman Foundation, 15th November 2010

[9] Financial Court Les prélèvements fiscaux et sociaux en France et en Allemagne, March 2011

[10] Jean-Marc Vittori L'impôt élevé, un choix français Les Echos 7th December 2010

[11] Laurent Cohen-Tanugi Quand l'Europe s'éveillera Grasset 2011

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :