Multilateralism

Ramona Bloj,

Eric Maurice

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

Eric Maurice

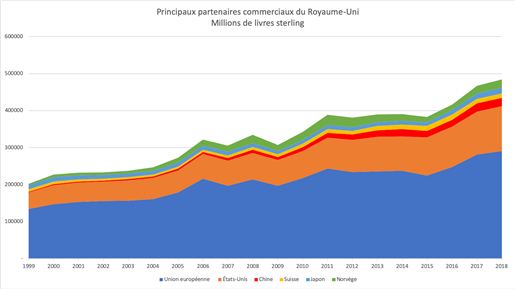

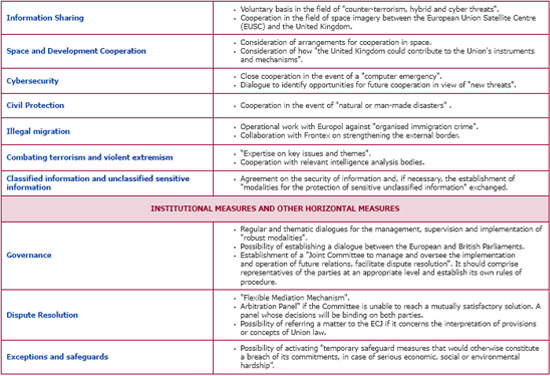

For the 27 Member States, the aim of these negotiations is simple: to maintain the closest possible links with what was the Union's third most populous country and its second largest economy, without undermining the achievements of European integration, first and foremost of which is the single market. The discussions will therefore be complex and difficult. According to the political declaration accompanying the withdrawal agreement, the aim is to establish "ambitious, broad, deep and flexible partnership across trade and economic cooperation with a comprehensive and balanced Free Trade Agreement at its core, law enforcement and criminal justice, foreign policy, security and defence and wider areas of cooperation"[1].

The EU will try to limit the negative impact of Brexit and to maintain European unity, while succeeding in concluding the negotiations before the end of the year. To this end, the 27 Member States have decided to retain the methodology which enabled them to successfully conclude the negotiations over the British withdrawal.

A gradual transition to permanent withdrawal

The transition period starting on 1st February should help to avoid a sudden break and to settle the final conditions of the withdrawal. It had been agreed earlier, for Brexit which should have taken place on 29th March 2019, for a period of 21 months, i.e. until the end of December 2020. The withdrawal agreement foresees that the United Kingdom and the European Union might extend it once by mutual agreement, for a maximum period of 2 years as decided by the Brexit negotiators on 22nd November 2018, i.e. until 31st December 2022.

Boris Johnson's government has nevertheless said it will not request such an extension. What will happen during this transitional phase?

Put simply, nothing will change. The European Union will treat the UK like any other EU Member[2], it will retain all of its access rights to the internal market and will continue to apply and therefore enjoy full Union rights, including the rules that are to be adopted during the transition period.

Moreover, the British will remain, even in the event of disagreement, under the authority of the EUJC (provided for in the 2019 agreement). In the event of a dispute over the agreement itself, political consultation will take place in a Joint Committee. If no solution is found, the dispute will be submitted to specific arbitrators as in all international agreements. The decision taken will be binding for both parties; in the event of non-compliance, the arbitration panel may fix a lump sum or penalty payment to be paid to the injured party[3].

The changes expected in the European institutions

While the United Kingdom has not appointed a Commissioner to the Commission chaired by Ursula von der Leyen, it is the turn of the European Parliament to take note of the departure of the British.

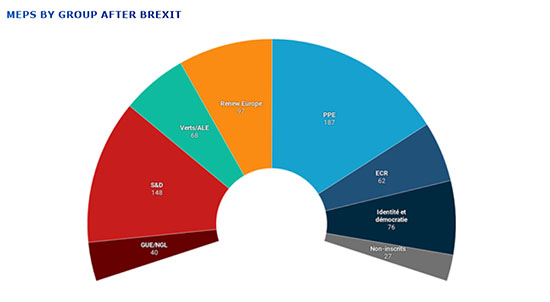

On 1st February 2020 only 705 MEPs will sit in Strasbourg as the 73 British MEPs will leave office. Of these 73 seats, 46 will be temporarily frozen in the event of further enlargement. The remaining 27 seats have already been distributed among several Member States: + 5 seats for France and Spain, + 3 seats for Italy and the Netherlands, + 2 seats for Ireland, + 1 seat for Romania, Austria, Denmark, Croatia, Finland, Sweden, Slovakia, Poland and Estonia. These Members of the European Parliament, elected in May 2019, will finally be able to sit. This new configuration in Parliament might lead to new balances of power within its ranks: Renew group will lose 11 seats, the Greens 6, the S&D 6, and GUE/NGL 1. The EPP will gain 5 seats, Identity and Democracy (ID).

Regarding the composition of committees and subcommittees, the list of members will be finalised once the new composition of Parliament has been confirmed, following the redistribution of seats between Member States[4].

It is also to be expected that the balance within the Council will be more fragile, in particular because of the qualified majority rule (Art. 16 § 4 TFEU).

Michel Barnier at the centre of affairs

The negotiations on the future relationship will be led by Michel Barnier, who led the ones on the conditions of the withdrawal and has managed to retain the confidence of the political and institutional players in Brussels and in the capitals of the Member States. He will be supported by a reinforced team of nearly 80 people, known as the Task Force for relations with the United Kingdom (UKTF) and attached to the Commission's Secretariat-General.

Michel Barnier, who has the rank of Director-General of the Commission, will have authority over all the Directorates-General to coordinate work on all aspects of the negotiations. The Commissioners, notably Phil Hogan, in charge of trade, will work closely with the Chief Negotiator.

From one negotiation to the next, and from one Commission to the next, some appointments reflect a concern to conduct the process as smoothly as possible. The new Director General for Trade is Sabine Weyand, former assistant to Michel Barnier, the lynchpin to the withdrawal agreement. Michel Barnier's second deputy in the previous task force, Stéphanie Riso, is now Deputy Head of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen's Cabinet. Michel Barnier's new deputies are Clara Martinez Alberola, who headed Jean-Claude Juncker's cabinet as Commission President, and Paulina Dejmek Hack, former economic advisor to Jean-Claude Juncker.

The structure established in 2017 to coordinate the work between the Commission, the Council, the Parliament and the capitals is also being maintained. The Task Force will be in permanent contact, particularly during the negotiation rounds, with the Member States, who will work in the Council under the leadership of Didier Seeuws. In the Parliament, the steering group, currently chaired by Guy Verhofstadt (Renew, BE), will be regularly informed by Michel Barnier.

A tight schedule

The first step will be to approve Michel Barnier's negotiating mandate. It will be presented by the Commission as soon as the United Kingdom withdraws, with the aim of launching discussions "at the end of February or the first days of March"[5].

Negotiations will take place in rounds of several days, with thematic groups working in parallel. Unlike the withdrawal process, some of these rounds might be held in London. An initial assessment will be made at a high-level conference between the European Union and the United Kingdom at the end of June. It is at that time that the two parties will have to decide, by 1st July at the latest, whether or not to extend the transition period beyond 31st December 2020 for 1 or 2 years, to allow themselves more time to conclude the negotiations.

1 July is also the date on which the European Union and the United Kingdom have committed to try to conclude and ratify a new fisheries agreement, which will, in particular, regulate access to British waters for European fishermen and the management of stocks jointly through annual quotas.

The date of 30th June is the deadline that the two parties have set to assess their respective equivalence in financial services, a process that will review some 40 sectors. The decision on whether or not to grant financial equivalence to the United Kingdom will be taken by the European Union, with no direct link to the overall negotiation and, in particular, trade.

A further reciprocal assessment will be carried out, until the end of the year, on personal data protection regulations and mechanisms, with a view to adopting "adequacy decisions" to allow the free flow of data between the EU and the UK. Priority in the evaluation will be given to respect for data and freedoms in the context of police and judicial cooperation.

For an agreement on the future relationship, be it comprehensive, commercial or extended to some sectors, to enter into force on 1st January 2021 after the end of the transitional period, it will have to be ratified by the UK and the EU. It must also have been approved by the European Heads of State and Government. The desirable timetable would therefore be the conclusion of an agreement at the beginning of October 2020, approval by the European Council on 15 and 16 October, and parliamentary ratification in November and December.

The actual negotiating time is therefore reduced to 7 or 8 months and EU leaders have already indicated that it will be extremely difficult to reach a comprehensive agreement in such a short period of time. As British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has for the moment ruled out any extension of the transition period, it is therefore necessary to define the priority aspects on which agreement is needed to avoid a "no deal" situation on 1st January 2021.

A three-part agreement

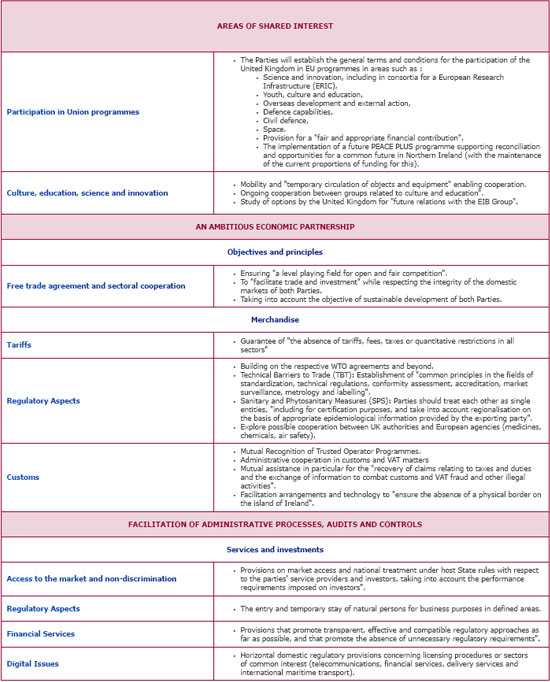

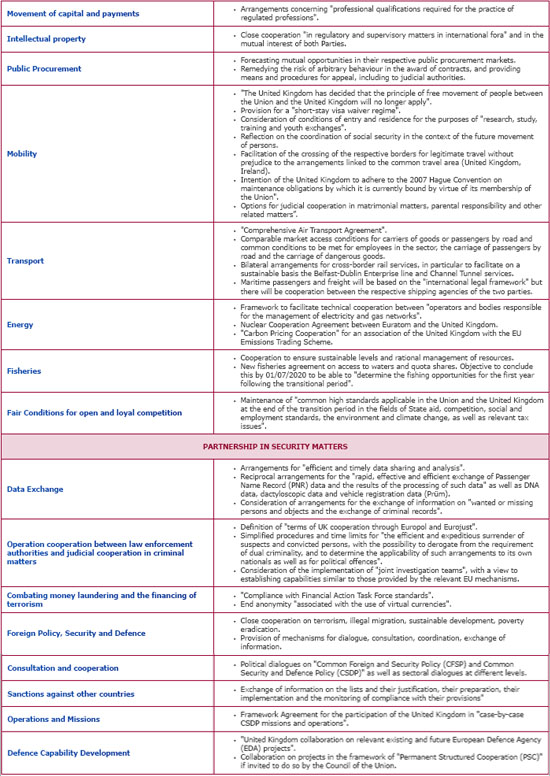

The Union is planning a comprehensive partnership agreement which will include three main components: a general component, an economic component and a security component. Supplementary agreements may be concluded at the same time or later.

Of all the areas of the future relationship to be defined, three are crucial to avoid a no deal in which the links between Europeans and the British would no longer be regulated: trade, fisheries and security (internal and external). These are the three areas on which the 27 Member States will focus their efforts as a matter of priority, while financial services, the sector in which the United Kingdom has a surplus balance with the European Union, could be negotiated in a second stage.

To simplify the ratification process, it will also be in the EU's interest to conclude, as a first step, an agreement containing exclusively "Community" provisions requiring only the ratification of the European Parliament. "Mixed" subjects, such as investment agreements, which also require ratification by national parliaments and some regional parliaments (43 in total), would also be negotiated at a later stage.

The heart of the agreement will be a free trade agreement, which Michel Barnier sums up with the formula "zero tariffs, zero quotas, zero dumping". But the absence or low level of customs duties and quotas will depend on the absence of dumping on the part of the United Kingdom. "The level of ambition of our future free trade agreement will be proportional to the level and quality of the rules of the economic game between us."

The concept of the "level playing field", which describes the European willingness to maintain quality rules of the game, is expected to play as important a role in the negotiations as the "backstop" in the discussions on withdrawal. It covers the maintenance of regulatory, fiscal and environmental standards as close as possible to European standards, on 1 January 2021 but above all in the future, to ensure that the European Union does not become an unfair competitor.

In parallel with the negotiations on the future relationship, the European Union and the United Kingdom will have to establish the protocol on the Irish border, which is the thorniest issue in the withdrawal agreement. A joint committee is to define which products will be allowed to cross the border between the British Province of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland - and thus enter the single market - and which will have to remain in Northern Ireland. The difference between the two categories will decide on the customs controls to be introduced between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. The organisation, responsibility and supervision of these controls must also be detailed.

***

The transitional period is decisive for the future relationship between the European Union and the first Member State to leave it, as is the transitional period for the completion of the withdrawal agreement. As in the first negotiations, there will be many issues that might ruin everything.

ANNEX[6]

The framework of future relations between the European Union and the United Kingdom

(Political declaration signed on October 2019)

[1] Political declaration establishing the framework of future relations between the EU and the UK, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12019W/DCL(01)&from=EN

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/fr/MEMO_18_6422

[3] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_18_6422

[4] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/fr/press-room/20200115IPR70329/composition-des-commissions-parlementaires-apres-le-brexit

[5] Michel Barnier, speech in Stockholm on 9th January, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_20_13

[6] Realised with Kenza Bensaid and Myriam Dziewit Benallaoua

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Climate and energy

Gilles Lepesant

—

14 January 2025

European social model

Fairouz Hondema-Mokrane

—

23 December 2024

Institutions

Elise Bernard

—

17 December 2024

Africa and the Middle East

Joël Dine

—

10 December 2024

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :