Strategy, Security and Defence

Quentin Perret

-

Available versions :

EN

Quentin Perret

I-Crisis Management and European Foreign Policies

A-The European Union in international relations

The development of a European capability for crisis management is the result of two movements: the extension of international competence of the European Communities since 1957 and the creation and development of the Common Foreign and Security Policy since 1992.

1) The Community and External Relations

The competences of the European Economic Community founded in 1957 were essentially economic and commercial. The monopoly of commercial relations between the Community and third countries has provided the European Commission with considerable weight in the international arena. Apart from the multilateral context of the GATT, Association Agreements have governed trade relations between the Community and certain States or third regional organisations since the 1960's. These Association Agreements were rapidly completed by Co-operation and Partnership Agreements that enabled the Community to extend its competence to domains such as co-operation, development aid and macro-economic support. Whilst negotiations relative to economic and political commitments linked to these Agreements led to in depth dialogue between the Commission and its partners the long term co-operation programmes were progressively completed by short term intervention tools designed to solve emergency situations and/or to launch the establishment of long term geographic tools. At the start of the 1990's the Community had a range of tools and instruments at its disposal enabling it to influence the internal development of its partners.

2) The Development of the Common Foreign and Security Policy

The application of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 heralded the birth of the European Union. It has been built on three pillars: the institutions and competences rallied together by the European Communities since 1957; police and judicial co-operation; the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) decided upon and launched by the Member States who met in Council [3].

The first draft of the Common Foreign and Security Policy dates back to 1992. With the end of the Cold War and the start of the war in Yugoslavia, the Western European Union put forward the re-organisation of the armies of Europe with three fundamental missions as a basis: humanitarian and evacuation missions; peacekeeping missions; combat missions to manage crises and re-establish peace. These so-called Petersberg Missions were then incorporated in to the Treaty on the European Union [4] on signature of the Amsterdam Treaty in 1997. The last treaty created the position of Secretary General of the Council of the European Union – High Representative for the CFSP (post granted to Javier Solana in 1999) providing the European Council with an enhanced orientation competence in terms of security and defence. In December 2000 the Nice Treaty decided the inclusion of the WEU within the European Union, created the permanent structures within the Secretariat General of the Council to address CFSP issues and defined Union relations generally with third countries and NATO in all matters related to defence.

The effective launch of the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) in fact dates back to the Franco-British Summit in Saint-Malo in December 1998. The objectives established during the summit with regard to European defence were ratified by the other Member States during the European Council of Cologne (June 1999). The European Council of Helsinki (December 1999) led to the definition of a Headline Goal that aimed to provide the EU with an (autonomous action capability supported by credible military forces" as well as by civil support forces [5]. The nature and importance of the civil capabilities were defined during the European Councils of Feira (June 2000) [6] and Göteborg (June 2001). In 2002, the ESDP was extended to the fight against terrorism whilst the modalities of co-operation between the ESDP and NATO were formalised [7]. In 2004 the Headline Goal 2010 was announced thereby extending and completing the Headline Goal defined in Helsinki in 1999 [8].

B- A European Definition of Management Crisis

The Petersberg tasks stress the maintenance or re-establishment of peace as well as the protection of civil populations; The European Strategy for Security published in 2003 adopted a more offensive notion of the European Policy for Crisis Management. The document highlights that in a world where "margins for manoeuvre" enjoyed by non-aligned organisations in playing a role in international affairs [9] had increased significantly since the end of the Cold War, European and international security could not be separated from the capability of all States to maintain order within their own territories. The "decline of States" which "undermine the world order and contribute to regional instability" appears therefore to be a serious threat. Re-establishing State authority in places where it is now absent or where is has disappeared comprises the ultimate aim of the European Policy for Crisis Management

When considered from the point of view of supporting or building States, crisis management operations comprise several phases: prevention, that attempts to prevent the start of internal conflicts and the collapse of central authorities; intervention, that aims to end internal conflict when this has started; stabilisation, that immediately follows intervention; and material and institutional reconstruction, that aims to re-establish legitimate and effective State authority.

II- Management Crisis in Action

A- European Players in Crisis Management

1) The Community Institutions

The European Commission deploys its external and crisis management policy using five Directorates General (External Relations, Trade, Enlargement, Development [10], Humanitarian Aid [11]) controlled by four Commissioners [12] that comprise the Commissioners' Group for External Relations presided over by the President of the Commission.

The crisis management tools at the Commission's disposal are mainly preventive and long term in nature [13]. The various geographic Agreements between the Community and its partners include various modalities that can have several objectives [14], such as political dialogue; economic and trade agreements; macro-economic support; co-operation and development aid; emergency aid; reconstruction aid [15]. The launch of these various tools and means is governed by the respect of certain political criteria by the Union's partners particularly with regard to good government. The Commission can also decide to suspend these Agreements within the context of sanctions adopted against a delinquent State [16].

Over the last few years the Commission has also provided itself with sectoral tools enabling it to act in emergency situations or in environments that are politically unstable [17]. These tools go beyond prevention and involve stabilisation and reconstruction phases both inside and outside of the Union borders. Their deployment is part of a rapid decision making system. The main instruments are:

• Exceptional and financial assistance;

• Long term financial instruments;

• The Rapid Reaction Mechanism (MRR) [18] ;

• The Civil Protection Mechanism [19].

The role of the Commission in the CFSP is much more modest [20]. The Unity for the Prevention of Conflicts and Crisis Management within the Department A (CFSP) of the RELEX DG is however responsible for co-ordinating the Commission's activities relative to the prevention of conflicts, notably action undertaken by the RRM. Its role comprises the provision of technical expertise with regard to all civil aspects pertaining to crisis management. It also participates in the strategic monitoring of potential crisis zones in co-operation with the Situation Centre. Its activities have notably enabled the integration of conflict prevention indicators within assistance programmes concluded with third countries.

2) The Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union is the permanent administration associated with the Council of Ministers. According to the Maastricht Treaty the latter is responsible for the definition and implementation of the Common Foreign and Security Policy. To do this it has progressively provided itself with a series of organisations that enable it to set down and apply a common crisis management policy.

• The High Representative and the Council Secretariat. The High Representative leads the Council Secretariat that is divided into nine Directorates. The DG E, for External Relations is itself divided into nine geographic or functional Departments. The DG E9 is responsible for managing civil crises. The Police Unit which answers to this directorate is an organisation that plans and undertakes missions in crisis management including the deployment of police forces; the Planning and Rapid Warning Unit (Political Unit), a geopolitical and strategic analysis tool at the service of the High Representative; and the Situation Centre (SITCEN), a unit to record, analyse and warn that runs 24/24 and 7/7.

The division of the Council responsible for defining the CFSP is the General Affairs and External Relations Council (GAERC) that brings together the Foreign Ministers from the Member States. The meetings of these are prepared by the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER). The GAERC is helped in its work by a series of organisations linked to the Council and the Secretariat:

• The Political and Security Committee (PSC/CoPS). The main player in the decision making process in the areas of the CFSP and the ESDP comprising ambassadors of the various Member States it ensures the "political control and strategic management" of the CFSP in co-ordination with the Military Committee and the Committee for Civil Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM), from which it receives opinions and recommendations and to which it addresses its directives.

• The Military Committee (EUMC) comprises the military chiefs of staff of Member States or their representatives and follows the development of military operations and draws up opinions and recommendations for the PSC on all military aspects of the ESDP. It leads the European Union Military Staff (EUMS).

• The EUMS fulfils three main operational functions: rapid warning, situation evaluation and strategic planning of Union missions. It is also responsible for the application of decisions to intervene according to the directives on the part of the EUMC.

• The civil-military cell aims to "enhance the EUMS's capability to ensure early warning, situation evaluation and strategic planning." It ensures the liaison between the Union's civil and military organisations within the framework of crisis prevention or management operations.

• An operation centre is to be available by the summer of 2006. It will comprise staff from EUMS and Member States.

• The Committee for Civil Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM), comprising representatives from Member States draws up recommendations and opinions for the PSC on the various civil aspects of crisis management: police, State of law, administration and civil protection. It develops concepts and instruments including capabilities relative to civil crisis management, it follows the development of civil operations and prepares solutions to crises.

• The Politico-Military Group (PMG) ensures the preparation of transversal subjects related to civil and military areas before they are examined by the PSC.

• The Group of Advisors for External Relations (RELEX) brings together external relations advisors from each permanent representation. Its mission is to deal with all horizontal aspects, notably institutional, legal and budgetary of the CFSP/ESDP.

3) The other players: alliances, regional organisations and third States

The hybrid nature of crisis management operations implies that the European Union rarely acts alone. The intervention phase that demands in particular the employment of force requires both an international mandate (generally the agreement of the UN Security Council) and the collaboration of organisations of third States, neighbours to the crisis zone or the EU's traditional allies.

Of the alliances that are likely to back European interventions NATO is one of the foremost [21]. Regional organisations with whom the Union works notably include the African Union [22] or the ASEAN. As for third States their contribution is now the subject of participation agreements [23], which govern the modalities of the work with the Union.

B- Crisis Management in Action

1) Decision Making

The European Union has provided itself with rapid decision making procedures enabling it to adapt its intervention tools to the various stages of a crisis.

We can distinguish the routine phase (monitoring, planning, anticipation and early warning phase); the development of the crisis and the drawing up of a concept to manage it (after the start of the crisis, if the PSC believes that EU intervention might be appropriate it draws up a Crisis Management Concept (CMC) which lays down the EU's political interests, the final objective as well as the main strategic options available); the approval of the concept and the development of strategic options (after approval of the CMC by the Council, the PSC tells the EUMC to draw up the strategic military options as well as any possible strategic options for civil and police action); the formal decision to act and the drawing up of plans (the Council can then, according to article 25 of the EUT delegate power to the PSC enabling it to ensure the political control and strategic management of the operation); the application of the chosen measures, finally the refocusing of EU action and the end of the operation [24].

2) Funding Operations

The funding modalities of operations are governed by article 28.3 of the Treaty on the European Union. Civil crisis management operations are funded by the CFSP budget (provided with a total of 62.6 million euro in 2005) [25], which is a part of the community budget managed by the Commission but the use of which is decided by the Council.

Operations that involve military intervention cannot however be financed by community funds. A part of this spending is mutualised and split between Member States according to their GDP. An administrative and financial mechanism called Athena manages joint costs since 2004 [26], from the preparatory phase to the end of operations [27]. The remainder of spending is financed directly by the Member States according to their participation. In practice less than 10% of the total cost of a military crisis management operation is mutualised.

3) Union Operations

For three years now the Union has increased the crisis management operations in which it is involved within its immediate neighbourhood. These operations include or have included all phases of crisis management.

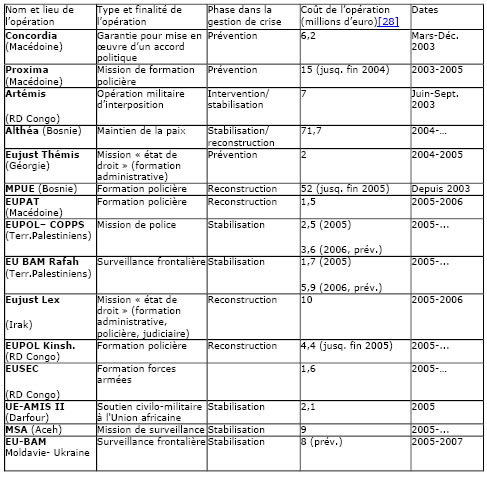

Table 1: Interventions Exterior to the European Union

III- Results and perspectives

A- Successes and inadequacies of European crisis management methods

The increase in crisis management operations undertaken by the European Union over the last few years makes it possible to draw up an overview of the results achieved by the "European crisis management method". According to many observers the EU's capabilities and know-how in terms of crisis management are far beyond those of NATO and the USA [29]. Inadequacies do exist however both in the EU's decision making process as well as in the intervention and action capabilities of the latter.

1) A problematic decision making process

The lack of one authority in terms of foreign policy comprises the main obstacle to the effectiveness and continuity of action external to the European Union. In addition to the division of competences between the Commission and the Council we must also include the permanent danger of disagreement between Member States within the Council itself.

With regard to the first of these divisions the Constitutional Treaty plans for one person only to assume the positions of European Commissioner for External Relations and the High Representative for the CFSP/Secretary General of the Council. The rejection of the text, in the expectation of a hypothetical adoption of its institutional measures leaves no other choice but that of ad hoc co-ordination solutions.

In March 2003 the Council drew up some "procedural proposals for global, coherent European crisis management" [30]. The most recent operations suggest that the Commission and the Council are now able to co-ordinate their crisis management tools very quickly in emergency situations [31]. The danger of rivalry and mutual contradiction still exists however and will not be overcome long term but for negotiation and strong political will on the part of the Member States.

In spite of the unity shown during recent external operations the latter are still separated by divergent geographic traditions and tropisms [32]. These differences have been attenuated until now by the relatively consensual nature of the operations undertaken, the military size and dimension of which have remained limited enjoying the agreement of both international and Atlantic institutions. A situation whereby the European Union was forced to undertake a major military operation alone would from this point of view be a true test. Such a situation would probably demand close co-ordination between France and the UK and between these two countries and their partners.

For the most ordinary crises European States' ability to act together appears to be increasingly satisfactory. The increased usage of enhanced or structured co-operation agreements seems to improve the ability for joint action [33]. In all events it is in the interest of each and every one that the co-ordination between Union members at each stage in the development of a crisis improves in the future.

2) The strengthening of military capabilities

In the wake of the programme adopted by the European Council in December 2004 the strengthening of the intervention capabilities of European armed forces is now a subject of discussion. Adequacies in this area have been identified [34] :

• Strategic Transport Capabilities. Since European capabilities with regard to this are insufficient the Union is forced to use equipment that is bought or rented from foreign partners, mostly from the USA, Russia and the Ukraine. The planning of the armed forces however depends on strategic transport capabilities. The completion of the A400M makes it possible in part to make good this inadequacy but the first deliveries will only be made in 2007 and the planned number is mainly believed to be insufficient.

• Standardisation and interoperability. This is a vital objective to enable the various European armies to act together. Its application is however particularly complex. The European Capabilities Action Plan comprises the first stage [35], which should be followed by a concerted action by the European Defence Agency.

• Strategic Information. The military chapter in crisis management demands detailed and up to date knowledge of the field which implies particularly effective human and technical means in finding information. This objective is notably confronted by a true lack of European information and the limits of co-operation between national information services. The progress made by the European space programme GMES from 2008 on should however offer the European Union particularly effective reconnaissance means in space.

3) The strengthening of civil capabilities

The European Council of June 2004 adopted an action plan for civil crisis management capabilities. This action plan identifies priorities with regard to enhancing and integrating European capabilities and establishes 2008 as the deadline for the completion of the Civilian Headline Goal 2008.

At the end of 2004, Member States provided the Union with 5,761 police officers, 631 State of Law specialists, 562 civil administrators and 4,988 civil protection staff. Commitments made by the various States within the framework of the Headline Goal 2008 were confirmed in 2005. The Conference on the Improvement of Civil Capabilities on 21st November 2005 did however identify the progress still to be made [36]. This involves in particular the rapidity of deploying civil personnel to the crisis zone and the quality of staff know-how. The Conference therefore proposed the establishment of a "target list" of inadequacies to be covered as a priority as well as work to improve staff training and the enhancement of co-ordination between Member States in this area, notably thanks to an exchange of "good practice". The Conference also proposed to increase the involvement of Member States in all stages of crisis management operations undertaken by the European Union and stressed the need for everyone to continue work in order to achieve the objectives established for civil capabilities by the CFSP.

For its part the European Commission has reworked its programmes for aid and co-operation to the benefit of the CFSP objectives in terms of resolving conflicts, managing crises and consolidating State structures [37]. In September 2004, it also proposed the establishment of a Stability Instrument designed to enhance the coherence and rapidity of European response to natural disasters. This process was speeded up after the tsunami in December 2004. After the Action Plan presented by the Luxembourg Presidency on 31st January 2005 the Commission proposed a series of measures in a Communication dated 20th April 2005 that was designed to "enhance the European Union's capability to confront crises and disasters in third countries" [38]. The measures put forward aim in particular to heighten the rapidity and response provided by the mechanisms to distribute humanitarian aid in crisis areas [39], to improve the coherence and co-ordination of national, community and international policies and to strengthen the Community Civil Protection Mechanism by "improving the links between Community programmes and the European Union's civil and military capabilities." On 27th January 2006 the Commission also suggested a series of measures designed to enhance the Union's Civil Protection Mechanism [40].

B- Moving towards a European culture of crisis management

Crisis management and State re-construction operations in a given territory are often likely to encounter numerous obstacles: uncertainty about the territory's international status [41], coexistence on this territory of opposing communities, existence of political and moral traditions that are incompatible with liberal democracy or even with a modern, bureaucratic, secular form of State [42]. European thoughts into crisis management cannot then only be limited to issues of procedure and capability must it must also encompass a theoretical dimension. Research into the area of comparative political culture and even issues of political philosophy should find a role in defining the Union's external strategy. It is by taking into account the possibility that its own political model is not applicable everywhere and by acting adequately as a result of this that the European Union will be better prepared to face the complexity and unforeseeable nature of crises that will occur in the 21st century [43].

Conclusion

In spite of the considerable progress made over the last few years it is still probably too early to conclude that the European method of crisis management is successful. Most of the operations undertaken by the Union are not yet complete; the question of the future ability of the territories thus covered to govern themselves and of the internal and international political legitimacy of their new governments still remains to be seen. Moreover these operations have until now been limited in size. No one can foresee how the Union and its States would react in the face of a major political-military crisis

Recent history shows quite clearly however that military power alone is inadequate in solving modern crises. Armed intervention that is not followed up by a concerted stabilisation effort accompanied by the reconstruction of a viable political structure runs, on the contrary, the danger of degenerating into uncontrollable disorder. The return of internal political order in a territory where there has been none comprises the fundamental challenge of modern times. Having now adopted a global approach, both military and civil, to crisis management and by continuing to enhance its capabilities to act and its analysis tools the European Union is asserting itself as a major vector of security on an international level.

[1] Cf. Francis Fukuyama, State Building, Profile Books, 2004, p. xvii-xx.

[2] This question is of even greater acuteness when, as is the case for the European Union, the general objective established for crisis management operations is the establishment of a liberal, democratic State.

[3] The Maastricht Treaty planned for the States to "ensure that their national policies were in line with common positions." The Treaty on the European Union maintains today that Member States should actively and unreservedly refer to the Union's external and security policy in a spirit of loyalty and mutual solidarity" (Heading V, art. 11.2)

[4] Heading V, art. 17.2.

[5] The overall objective defined in Helsinki in 1999 plans for the creation of a Rapid Reaction Force of 60,000 men, deployable within 60 days for a period of a year.

[6] Commitments made in Feira in terms of civil capabilities comprise four chapters: the creation of a European police force of 5,000 men, 1,000 of which would be deployable in 30 days; the provision of 200 experts in the domain of the State of Law (judges, prosecutors and lawyers), comprising a rapid response group deployable within 30 days; the creation of a body of expert in civil administration and the creation of two or three teams of ten expert in civil protection who are able to travel within hours to a disaster area as well as a civil protection force of 2,000 men deployable at a later date.

[7] By the so-called "Berlin plus" agreements (December 2002). These agreements comprise four main points: the availability of NATO operational planning capabilities for the EU in ESDP missions; the inclusion of this availability in the establishment of the EU's military plans; access by the EU to NATO command structures (including those of the Vice Supreme Allied Commander for Europe) for the launch of European operations; inclusion in NATO's planning system of the availability of Alliance forces for European operations. The implicit condition of these agreements is that the Union will not engage in an operation itself if NATO is not involved.

[8] The new Headline Goal 2004 includes both an extension of the Petersberg tasks (now including joint disarmament operations and the support of third States in the fight against terrorism and the reform of security services) and the enhancement of European military capabilities thanks to the application of the European Defence Agency. The informal summit of Defence Ministers in Noordwijk (September 2004) also decided on the creation of 9 "battle groups". These battle groups comprise 1,500 men deployable within 10 days for a period of at least 30 days (120 thanks to rotation). The number has been increased since then. The creation of the European Gendarmerie Force of 3,000 men deployable in 30 days and able to serve in each phase of a crisis was also decided upon in Noordwijk.

[9] Amongst these "non-aligned" groups the documents makes particular mention of "terrorism" and "organised crime".

[10] European Aid for Development programmes are applied by the agency EuropeAid.

[11] Humanitarian aid programmes are co-ordinated and applied by ECHO (European Communities Humanitarian Office). The budgetary line dedicated to these programmes totalled 490 million euro in 2004.

[12] The Development and Humanitarian Aid DG's are governed by one Commissioner, at present Louis Michel.

[13] Cf. Commission Communication on the Prevention of Conflicts, COM (2000), 11 April 2001.

[14] Cf. Civilian Instruments for EU Crisis Management, European Commission Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management Unit, April 2003. http://europa.eu.int/comm/external_relations/cfsp/doc/cm03.pdf

[15] Thanks to the European Agency for Reconstruction established in 2000.

[16] Economic and trade sanctions adopted against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1998 and 2000 helped towards the positive political development of this country.

[17] Art. 308 of the TEU includes the possibility of creating if necessary new community instruments to manage crises.

[18] This mechanism is both an autonomous emergency instrument and a transition mechanism opening the way to long term aid programmes and to the main community co-operation instruments. It is funded by a specific budgetary line.

[19] The mechanism co-ordinates aid to the Union's member countries and five other European countries that have suffered disaster, both internal and external to the Union's borders. It comprises the provision of emergency aid materials to populations in the days following the disaster.

[20] The amount allocated to the Commission's CFSP programmes were lower than 50 million euro in 2004 ie 0.6% of the budget dedicated to External Relations (the percentage dedicated to financial transfers over to future Union Member States was for its part over 40%).

[21] Responsible for the stabilisation forces in Bosnia and Kosovo at present until 2004.

[22] Established on 19th April 2004, the Peace Support Facility for Africa aims to "enhance the African Union's capability to start support and peacekeeping operations." 250 million euro, taken from the European Aid to Development Fund will used to support the African Union's initiatives with a view to resolving conflicts in Africa. This Facility that was notably used to support the African Union's intervention in Darfour completes the European Co-operation and Training Programmes for African Police and Armed Forces.

[23] Cf. House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee, 10th Report, Section 9 (3rd March 2004) and 17th Report, Section 8 (7th May 2004). http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmeuleg.htm

[24] Cf. le Petit Guide de la Politique Européenne de Sécurité et de Défense published by the Permanent Representation for France at the European Union, p. 25-26.

[25] The sum in discussion at present for 2006 is 102 million euro.

[26] Cf. Council decision n° 197/04, 23rd February 2004.

[27] Except for Denmark, which benefits from an exemption clause.

[28] Reference amount decided upon by the Council when the decision to intervene is taken.

[29] Cf. James Dobbins, “Friends again?”, EU-US relations after the crisis, Security Research Institute of the European Union, 2006, pp. 26-28.

[30] Council Secretariat Document N° 7116/03.

[31] Cf. Pierre-Antoine Braud, Giovanni Grevi, The EU Monitoring Mission in Aceh: implementing peace, Security Research Institute of the European Union, Dec. 2005, p. 33-35.

[32] Traditional differences oppose for example the "big" States, holders of a complete range of military equipment (UK, France) and the others, more reticent with regard to the employment of force. Another difference opposes the "Atlantist" States (UK) against the supporters of "multilateralism" (France). Historical heritage and geographic position also define the diplomatic priorities of the various States to a great extent. The six monthly rotation of the Presidency of the Council tends to institutionalise these differences on a Union level and comprises a dispersion factor for the CFSP. The draft constitutional treaty plans for the election of a President of the Council for a two year and half renewable period.

[33] Enhanced co-operation agreements offer the possibility to a limited number of Member States to employ the Union's structures and capabilities for a joint action. The Nice Treaty extended this procedure to the CFSP pillar except in the domains of the armed forces or defence. Structured co-operation agreements apply more particularly to work towards harmonising Member States' military capabilities. Battle groups are the most obvious example.

[34] Cf. International Crisis Group, EU Crisis Response Capability Revisited, Europe Report n°160, 17 January 2005, pp. 25-26.

[35] The European Capability Action Plan (ECAP) was adopted by the European Council in Laeken (December 2001). Its application depends on the creation of working groups within which several States try to identify areas of synergy and to promote common solutions to technical questions.

[36] Cf. Ministerial declaration published after the Conference to Improve Civil Capabilities, 21st November 2005. http://ue.eu.int/ueDocs/newsWord/fr/gena/87043.doc.

[37] Cf. Commission Communication on the Prevention of Conflicts, 11th April 2001.

[38] Cf. Commission Communication: Reinforcing EU Disaster and Crisis Response in Third Countries, COM (2005), 20th April 2005.

[39] The Commission suggests in particular the creation of a European Volunteer Corps for Humanitarian Aid whose work would be co-ordinated with those of the UN.

[40] IP/06/89, 27th January 2006.

[41] This is the particular problem in Kosovo whose final status is to be decided upon at the end of negotiations on going at present.

[42] Cf. Francis Fukuyama, State Building, op. cit., p. 39-41.

[43] Cf. also Robert Cooper, The Breaking of Nations: Order and Chaos in the 21st century, Grove Press, 2004.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :