Analysis

Elections in Europe

Pascale Joannin

-

Available versions :

EN

Pascale Joannin

Starting on 6 June through 9 June, to take account of the voting traditions of each country, Europeans are being invited to elect the 720 representatives of the European Parliament, fifteen more than at present to reflect demographic changes. Three countries will gain two seats, and nine countries one more.

With a month to go before the vote, there are still many uncertainties surrounding this election, which represents the first stage in the renewal of the institutions of the European Union that will then ensue, i.e. the new Commission and the appointment of the President of the European Council.

The two main lessons to be learned from the 2019 elections

Turnout

In 2019, the European elections were a pleasant surprise, with voter turnout rising above 50% for the first time since 1994. Is it possible that this upturn in turnout will continue this year? Numerous studies show a growing interest among voters in a ballot that is still relatively unknown. But will this interest be reflected in voting?

Furthermore, since young people participated more in the 2019 ballot, some states have lowered the voting age to 16 (e.g. Germany) in the hope of attracting new voters and consequently a higher turnout.

Finally, a number of civil society campaigns have sprung up across Europe to raise awareness of the European vote and encourage people to get out and fulfil their civic duty.

A new political balance

A political earthquake occurred in 2019. For the first time since elections have been held by direct universal suffrage (1979), the two main political parties, the European People's Party (EPP), on the right of the political spectrum, and the Party of European Socialists (PES), on the left, together failed to win an absolute majority. This put an end to the duopoly it had held since 1979. And that situation seems truly to be over.

A third party was therefore needed to form a majority coalition: the Liberals, with whom the EPP had once governed (between 2002 and 2004, when Pat Cox was President of the European Parliament).

This tripartite coalition (EPP, PES Renew) is likely to happen again this year.

Some are hoping for a change of coalition, putting an end to the "grand coalition" (right-left) that has been in place for so long (too long) and bringing in an alternative, right-wing majority. Some polls are giving grist to the mill of supporters of this thesis, one of whose emblematic figures is the President of the Italian Council, Giorgia Meloni, who has decided to run in these elections, even if she will not ultimately sit in the European Parliament to "reproduce in Europe" what she succeeded in doing in 2022 in Italy. But is this even possible?

Specific features of the ballot: 27 elections~

Voting takes place everywhere according to the proportional representation system, which is customary for everyone except the French, who elect their national deputies by a two-round majority system. The proportional system means that it is impossible for a single party to have a majority. A coalition is necessary. Since 2019 it seems that it is no longer possible to have a coalition with just two parties; at least one more is needed to build these majority compromises in the European Parliament.

But the ballot contains a number of country-specific features. There may be a minimum threshold for representation (5% in 9 Member States, 4% in 3 Member States, 3% in Greece and 1.8% in Cyprus) or none at all, as in 13 Member States for example. Different rules, with varying degrees of parity, are in force in different countries to ensure better representation of women. The voting age is not the same in all countries (16 or 18).

As the transnational list project devised during this legislature for the 2024 ballot failed to be successfully implemented, there will be a succession of 27 elections held within a national framework, with players who are little known outside their country of origin, programmes defined on the basis of national priorities and not by the "manifesto" drawn up by a European party, and campaigns that differ from one country to another depending on the national political situation. The result is a juxtaposition of 27 results on 9 June, which then have to be Europeanised on the basis of electoral affinities, the parties having won seats and having formed political groups.

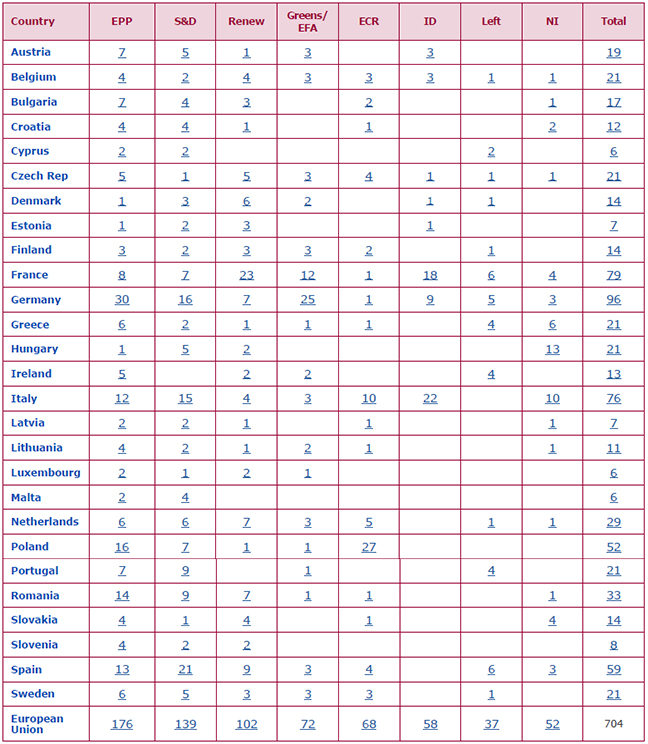

There are currently 7 political groups as follows:

MEPs by Member State and political group

Source : European Parliament

A surge expected on the right

A wave, not a tsunami

According to the most recent polls, it would appear that voters are tempted to vote for a party on the right of the political spectrum: the populist, nationalist, radical or even extreme right. In France, the Rassemblement National is credited with 30% of the vote, far ahead of the other parties. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni's Fratelli d'Italia is in the lead with 28.5% of the vote. Elsewhere, however, the gap between these parties and their closest rivals is narrower (e.g. Austria). In Germany, the AfD, after a long period of positive, high results, is now likely to get just 15% and the Lega in Italy 8%. A swing to the right is therefore likely, but it will not be as strong as was predicted a few months ago. So, it will not be a tsunami causing a full-blown landslide. The only uncertainty is which of ECR or ID will be ahead of the other, and whether one of them manages to overtake the Liberals in extremis.

The radical right in disarray

One of the reasons for the smaller scale of this wave is that the radical right is currently divided into two groups in the European Parliament: ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists) and ID (Identity and Democracy). This division is due to major political differences such as, for example, support for Ukraine expressed by the parties sitting in the ECR group and a favourable bias towards Russia for the parties sitting in the ID group. These deep-seated differences seem difficult to reconcile, and it is likely that this division will persist after the vote in June. — especially since some representatives of this trend are not attached to either of these two groups and sit as non-attached members (e.g. Fidesz in Hungary). This makes it even more difficult to understand the coherence of this right-wing movement.

A system on borrowed time?

In 2014, the European parties introduced the Spitzenkandidat system ("head of list" in German) as a more democratic way of appointing the person to chair the European Commission. The aim was to strengthen the link between citizens and the President of the Commission, who had historically been appointed by the European Council, and to encourage voters to cast their ballots in the European elections that take place every five years. By voting for a party, the electorate indirectly chooses the holder of the presidency, which is entrusted to the leader of the party that comes out ahead in the European elections. Each European party can select its candidate in advance. This system was successfully tested in the 2014 European elections. The Spitzenkandidat of the leading party, Luxembourg's Jean-Claude Juncker (European People's Party, EPP), became President of the European Commission.

This was not the case in 2019. As Jean-Claude Juncker did not stand for re-election, the EPP chose Germany's Manfred Weber as its Spitzenkandidat. Since the EPP again came out ahead in the European elections, its candidate might have hoped to enjoy the same trajectory as in 2014. But Weber had not, like Juncker, been Prime Minister of his country for 18 years! The Heads of State and Government therefore took over and proposed, as provided for in the Treaties, a German woman from the EPP, Ursula von der Leyen, without her having been a candidate. This was hotly contested by the European Parliament, where Ursula von der Leyen was finally but narrowly endorsed.

The outgoing President of the European Commission is standing for a second term. This time with the support of her party, the CDU, and that of the EPP, which she won, albeit not unanimously, at the party's Congress in Bucharest on 7 March. Like the EPP, eight other parties have designated a head of list. A televised debate between them took place in Maastricht on 29 April. According to our calculations, the EPP group will again take the lead on 9 June, so Ursula von der Leyen should be re-elected. Unless, as in 2019, the European Council comes up with another candidate.

Which coalition majority?

Despite the tendencies expressed in various quarters, a scrupulous examination of the polls in all the Member States, presented in the annex shows that the two main parties, the EPP and the PES, will still be in office on 9 June, even if they lose a few seats; these two parties will no longer have the majority they lost in 2019 however and they will need to find a partner to form a majority coalition. Although the Liberals are likely to lose more seats than expected, they should retain enough to renew the same coalition, the only one with an effective majority.

European Parliament’s new face

Contrary to some rather hasty opinions, despite these trends and the high degree of nationalisation of the ballot, the composition of the European Parliament resulting from the June 2024 elections is unlikely to undergo any real upheaval.

Political Europe, for a time shaken by national protests, subject like other democracies to legitimate challenges, questioned by the changing international situation, is still relatively stable overall.

These are the conclusions reached by the Robert Schuman Foundation's leading experts, supported by their unique European network, following an in-depth analysis of the electoral campaigns and the estimates already published.

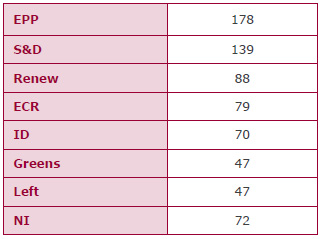

Composition of the European Parliament after the June 2024 elections (forecasts)

NB: breakdown based on the declaration of European groups and parties as known to date. Does not anticipate movements and affiliations that may take place after the ballot, particularly for non-attached members.

***

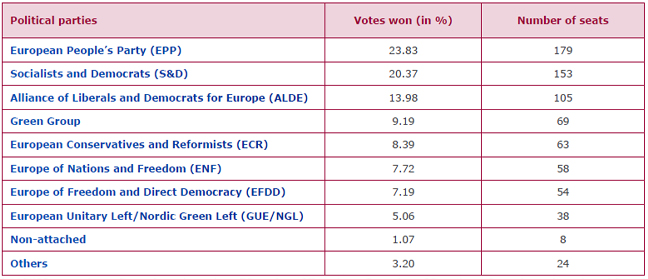

Results of the European elections on 23-26 May 2019

Source : European Parliament

NB: in 2019, the United Kingdom, which was negotiating to leave the European Union, took part in the European elections, although its departure had not been formally approved.

Annexes

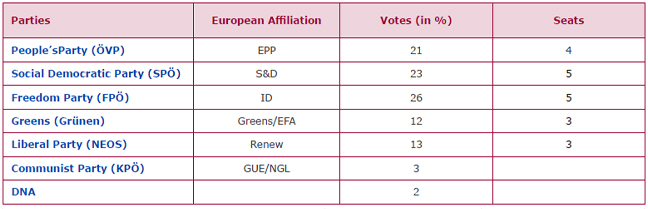

Austria

20 MEPs

https://www.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/austria/

7 lists

Source : https://www.bmi.gv.at/412/Europawahlen/Europawahl_2024/start.aspx

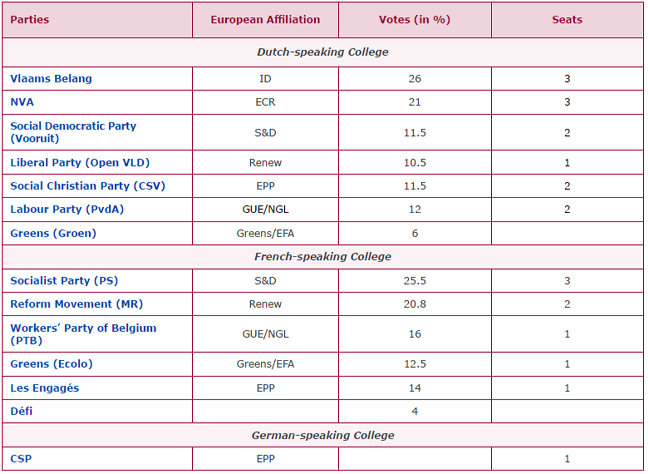

Belgium

22 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/belgium/

16 lists

Source : https://elections.fgov.be/informations-generales/numeros-nationaux-et-sigles-proteges

NB. The federal legislative elections are held on the same day as the European elections.

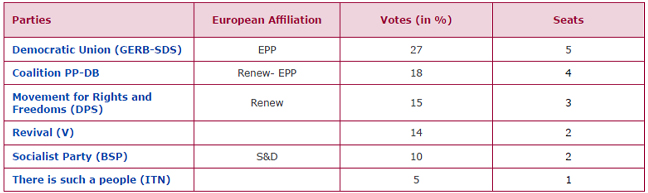

Bulgaria

17 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/bulgaria/

15 parties and 7 coalitions

Source : https://www.cik.bg/bg/decisions/3267/2024-05-09

NB. Legislative elections are held on the same day as the European elections.

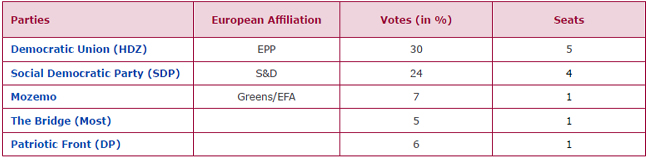

Croatia

12 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/croatia/

25 lists

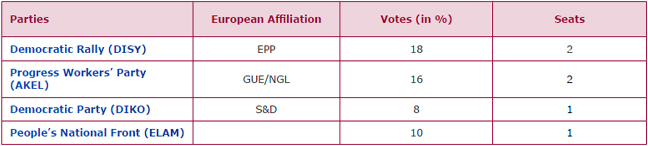

Cyprus

6 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/cyprus/

12 lists

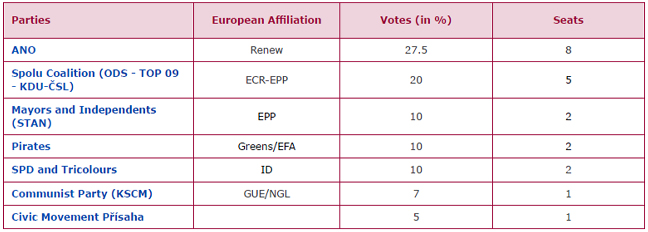

Czech Republic

21 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/czech-republic/

30 lists

Source : https://www.volby.cz/pls/ep2024/ep23?xjazyk=EN

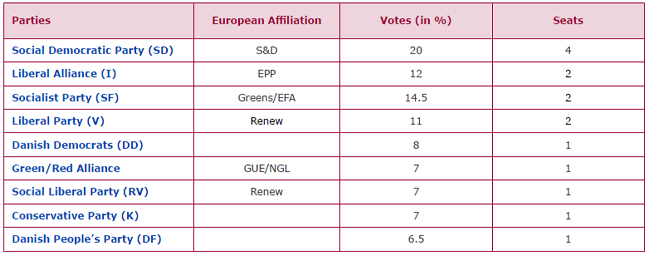

Denmark

15 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/denmark/

11 lists

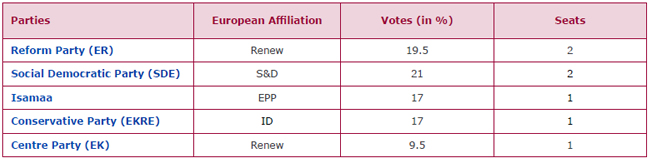

Estonia

7 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/estonia/

9 lists and 5 independents

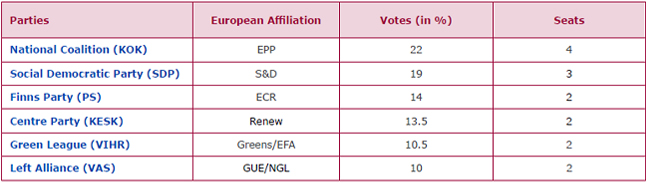

Finland

15 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/finland/

15 lists

Source : https://tulospalvelu.vaalit.fi/EPV-2024/en/ehd_listat_kokomaa.html

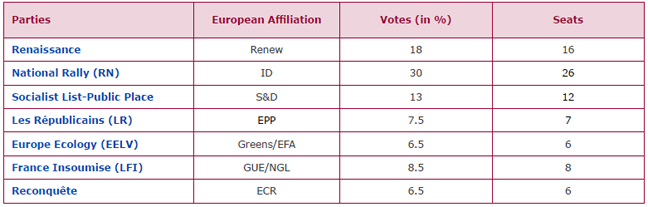

France

81 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/france/

NB: The closing date for submitting lists is 17 May.

Source : https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000049285193

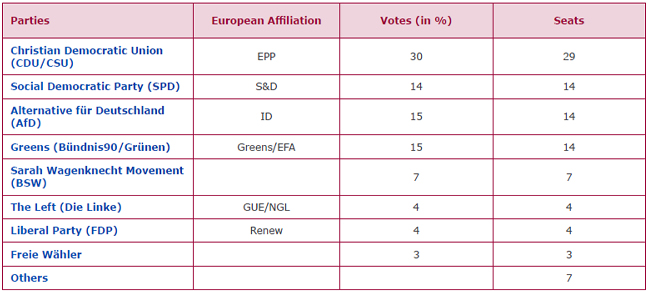

Germany

96 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/germany/

35 lists

Source : https://www.tagesschau.de/europawahl/parteien_und_programme/europawahl-2024-parteien-100.html

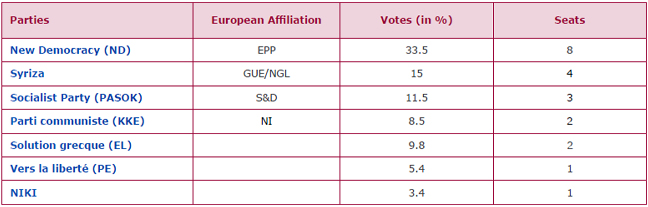

Greece

21 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/greece/

31 lists

Source : https://www.ypes.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FYLLADIO-EPISTOL-PSF-FINAL-20240510.pdf

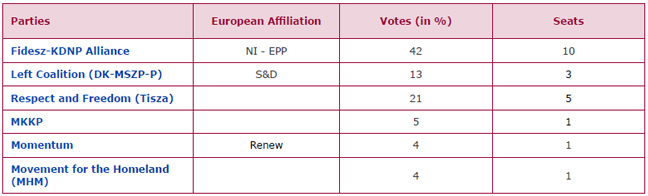

Hungary

21 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/hungary/

11 lists

Source : https://vtr.valasztas.hu/ep2024/valasztopolgaroknak/jelolo-szervezetek?tab=lists

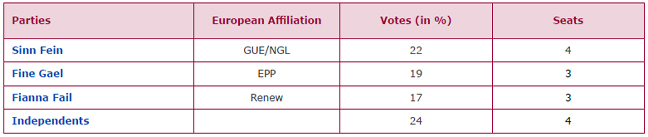

Ireland

14 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/ireland/

29 lists

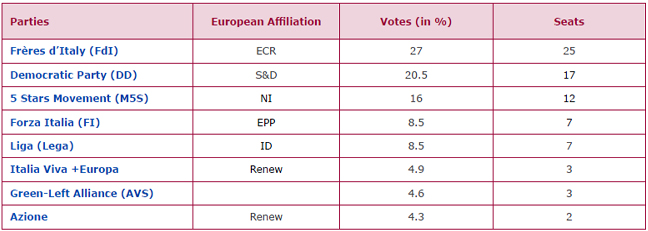

Italy

76 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/italy/

42 lists

Source : https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/eligendohome/deposito/europee/20240609/depositati

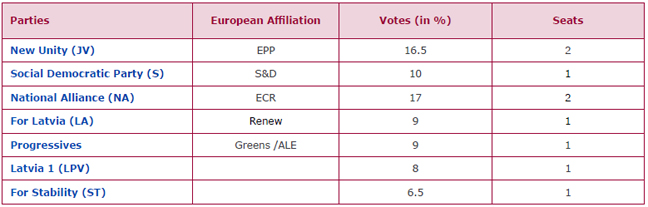

Latvia

9 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/latvia/

16 lists

Source : https://epv2024.cvk.lv/kandidatu-saraksti

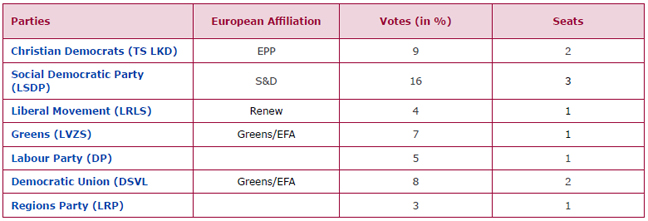

Lithuania

11 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/lithuania/

15 lists

Source : https://www.vrk.lt/kandidatai-kandidatu-sarasai-2024-ep

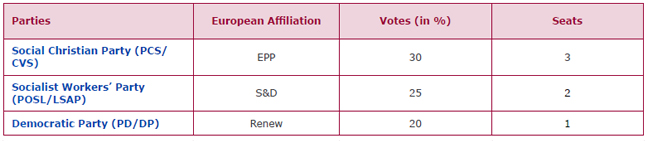

Luxembourg

6 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/luxembourg/

13 lists

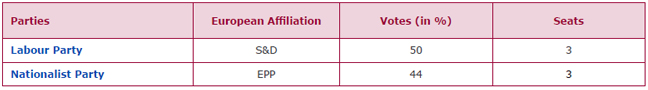

Malta

96 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/malta/

6 lists and independents

Source : https://electoral.gov.mt/pr7-29-04-24-en

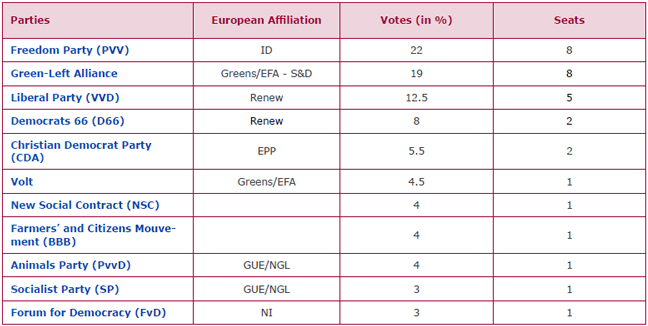

Netherlands

31 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/netherlands/

20 lists

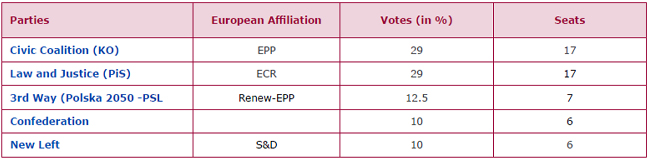

Poland

53 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/poland/

11 lists

Source : https://wybory.gov.pl/pe2024/en/kandydaci?kolejnosc=3_asc&strona=12

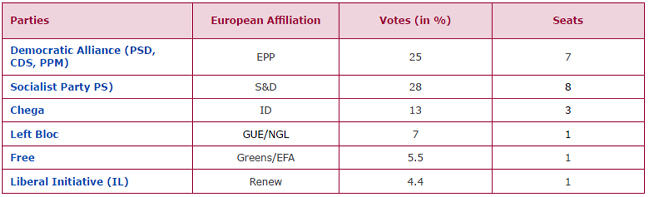

Portugal

21 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/portugal/

17 lists

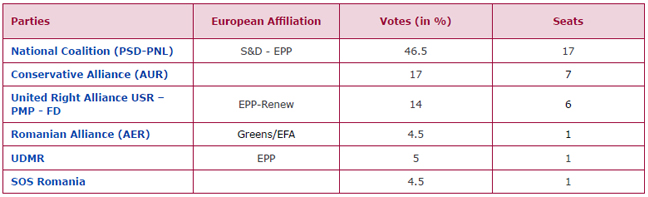

Romania

33 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/romania/

16 lists

Source : https://europarlamentare2024.bec.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/specimen_BV.pdf

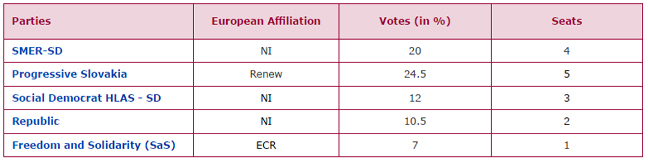

Slovakia

15 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/slovakia/

24 lists

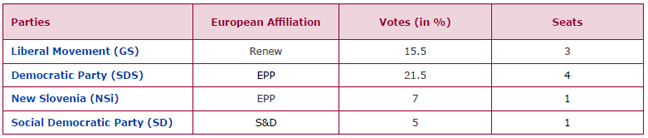

Slovenia

9 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/slovenia/

11 lists

Source : https://www.dvk-rs.si/

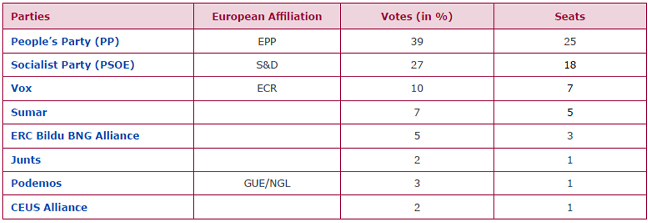

Spain

61 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/spain/

39 lists

Source : https://www.juntaelectoralcentral.es/cs/jec/documentos/candid_present_UE_080524.pdf

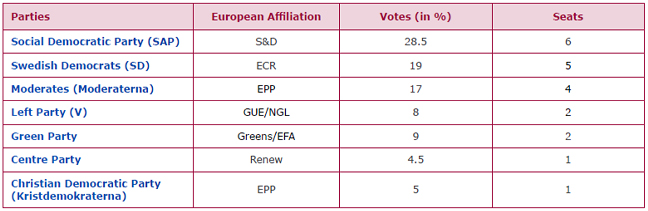

Sweden

21 MEPs

https://2024.electionseuropeennes.eu/en/sweden/

15 lists

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

4 November 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

28 October 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

14 October 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

7 October 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :