Internal market and competition

Jean-Paul Betbeze

-

Available versions :

EN

Jean-Paul Betbeze

Economist, Member of the Scientific Committee of the Robert Schuman Foundation

The hearings of the candidates for the Ursula von der Leyen II Commission just began on November 4, marked by a polite but firm call to order stemming from the Draghi Report published on September 9. The European Union has to get on track for more growth and jobs in a world that is moving faster than the EU is at present, and the European Commission, which holds the entire legislative initiative, has to be shaped accordingly.

A harsh assessment of Europe’s relative economic situation from the Draghi Report

Since 2019, production per European worker has grown by 0.5% a year, compared with 1.6% in the United States. With such a gap, the economic disparity between the two real GDPs has widened, from 17% in 2002 to 30% in 2023. According to the World Bank, the European Union is still the world's second largest economy, with a GDP of $18,400 billion, compared with $27,500 billion for the United States, followed by China with $17,800 billion. Of course, populations have to be taken into account. While GDP is as much an economic as a political yardstick for assessing what is at stake, GDP per capita is mostly economic, with $12,500 per Chinese, $81,700 per American and $40,800 per European.

So, it should come as no surprise that, again according to this report, the European Union would need to invest an additional €800 billion a year if it is to hold its rank. This would require investment to rise from 22% to 27% of GDP, with more loans coming from internal and external savings. It is easy to see why Mario Draghi chose ‘The future of European competitiveness’ as the title for his report. This powerful message, skilfully presented, cuts to the chase without ruffling any feathers, focusing on competitiveness, in other words on the struggle that succeeds. This report cannot easily be dismissed, even if its main thrusts or some of its detailed recommendations are open to criticism. It is indeed a demanding guide.

‘It is up to us to take action in Europe,’ says the report. So, we have been warned. As if that were necessary! It suggests pathways, figures, binding targets in terms of GDP, measures to be taken and structures to be modified, necessity being the law... The MEPs held talks on September 17 with Mario Draghi, who summarised his report, that was commissioned last year by Ursula von der Leyen. It is now up to them to assume their responsibilities, to resist the lobbies and critics, to be daring and to ensure that every member of the next College of Commissioners is moving in this direction.

No one will be able to say that they were unaware of the situation: there are ways out of the vicious circle in which we find ourselves, caught between the two world powers, the United States and China, a trap that threatens to crush us. As in 1939 in France, until now, we have adopted a defensive logic, this time that of norms. This logic, which was supposed to protect, is paralysing us in the face of accelerating change, which is evident everywhere. We are underestimating the geopolitical dynamics that are taking place. On the one hand the USA whose primacy is more contested, is concerned about Asia, not to say China, to which they are "pivoting" their resources. On the other hand, China is creating and developing its global network, with “the Silk Roads” which are becoming as much military as they are economic. The United States is concentrating its strategic activities and knowledge at home. It is investing to contain and curb China's advance, delivering high-tech products in a piecemeal fashion. The USA are paying to help Ukraine to buy their weapons. Russia sees all of these manoeuvres and thinks that a way is opening up in Europe to regain the territories abandoned by the USSR. And as the Soviet Empire awakens, Turkey looks with nostalgia at the Ottoman Empire: everyone dreams of going back in time. Against this backdrop, Europe absolutely must rely on its own strengths, uniting them more effectively. It must stop spreading itself too thinly and quarrelling with its neighbours and look beyond the Maginot line of its own norms towards the world that is moving forward. This is why the report proposes solutions, based on the watchword of competitiveness, just as the Coal and Steel Community did in 1952. It is all about building peace, by being more united and stronger. History reminds us of this, eighty years after 1945. Peace is a balance of power, internally so as not to become exhausted in quarrels, externally so as to carry weight in the world, first and foremost economically, hence the title of the report, a materiality that fools no-one.

Harsh assessment, bold proposals

As we have seen, the report opens with a very gloomy diagnosis: Europe has been losing ground to the United States in terms of growth since the turn of the century, with an ominous future: two million fewer workers per year, due to ageing. Europe can play for time by maintaining its 2015 productivity rate: its real GDP would ‘last’ for another twenty-five years, but the aftermath would be calamitous. This slowing competitiveness will take no quarter. Gradual at first, it will end up creating a rift. This calls into question the models of our companies and our societies, given the massive amount of investment and training required.

The situation is indeed worrying. In 2023, according to the report, taking GDP at constant prices, the European Union will be slowing down, having been surpassed by China for several years and 30% below the United States, compared with 17% in 2002. It would account for 17% of nominal world GDP in 2023, as much as China, compared with 26% for the United States. There is no need to point to the income share of the richest 10% to believe that everything can be explained and solved (through taxation) in Europe. It comprises 35% of the total, compared with 40% in China, 50% in the United States and 55% worldwide. The European Union is therefore relatively more equal in a world that is becoming more unequal, and it is decelerating. Productivity accounts for three quarters of this slippage. This is where action is needed.

The lag in innovation is obvious: of the world's fifty leading technology companies, only four are European. This sector will account for 18% of global revenues in 2023, compared with 22% in 2013, while the United States' share has risen from 30% to 38% over the same period. In this context, decarbonisation and competitiveness go hand in hand. Electricity prices in Europe which are two to three times the price of those of the USA, and those of gas are four to five times higher: nothing will be possible for industry and the economy if these gaps are not reduced. It is imperative that we decarbonise and move towards a circular economy, which implies being less dependent on strategic materials (copper, nickel, cobalt, graphite, rare earths), and on a few countries – where China dominates -, with a stronger space and defence industry. Not forgetting that this commercial and industrial policy must go hand in hand with a concern for social cohesion, which will not be easy.

All of this implies major funding commitments, with profound changes in terms of the logic of our banking and market systems. Europe is going to have to mobilise more resources, which means overhauling its banking system by making it more efficient, more concentrated and more interconnected, with financial markets taking on a greater role. Nothing will be possible without strengthened governance in a Europe that understands the importance of its financial needs. They imply a common strategy to encourage the birth, expansion and consolidation of innovative firms. This also implies growing budget deficits, and therefore a revision of the limits of European deficit and debt. In fact, the amounts available will be insufficient given the budgetary difficulties of a number of countries (consider France and Italy, not forgetting Germany, which is holding back). This means establishing a common financing policy based on a single savings and investment market, with banks making riskier loans and, above all, quasi ‘bonds’ from a European Treasury, which needs to be developed. But this is not self-evident when it comes to moving from general observations to this type of proposal, and even less so when it comes to the details, which is where the devil lies.

Sectoral and horizontal policies require short-, mid- and long-term goals

The report then launches into policy proposals by major sector: energy, critical raw materials, new technologies and networks, artificial intelligence, semi-conductors, clean energy, automation, defence, space, pharmaceuticals and transport. Each time, it presents the strengths and weaknesses of the sector, compared with what is happening in the United States and China, and concludes with a series of objectives and proposals with timeframes for achieving them. It is clear that this document is exceptionally rich and that there are many areas that need to be explored if it is to be put into practice.

This analysis is complemented by an examination of the ‘horizontal policies’ needed to close the competitiveness gap. This involves speeding up innovation, training to close the ‘skill gap’ and investing more in areas where it is crucial. Given the sums of money involved, and the issues at stake, nothing will move forward without a reorganisation of the European Union's structures. It is at this point that the Draghi report describes in detail what will be required to make its proposals effective. This begins with the Competitiveness Coordination Framework (CCF): by focusing efforts around the European Semester and the National Energy and Climate Plans, and by implementing the choices, with objectives, governance and financing. It is clear that according to the report, all of this will bring together and monitor the various programmes, applying the principle of subsidiarity as appropriate. This will involve extending the scope of qualified majority voting instead of using the restrictive unanimity vote, which certain ‘small’ countries can use to blackmail others. The rules also need to be simplified, with the European Union issuing 13,000 new regulations between 2019 and 2024, compared with 5,500 in the United States. These rules are constantly amended and accumulate, with no measure of their costs compared to their benefits. Hence the idea of reducing companies' reporting obligations by a quarter, and by up to half for SMEs, which artificial intelligence technology should help to achieve.

To Arm?

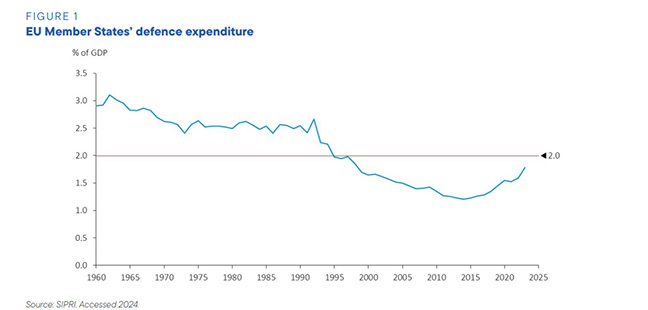

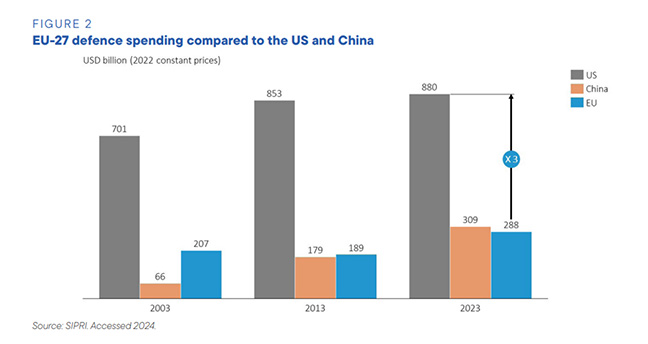

This is the discreet area of the report, illustrated by two striking graphs.

The first (cf. Figure 1 below) shows the development of European defence spending as a proportion of GDP from 1960 to 2025. The second one (cf Figure 2 below) shows US defence spending in the USA, Europe and China in 2003, 2013 and 2023.

Source : Part B, chapter 7, p. 160.

Source : Part B, chapter 7, p. 161.

Europe spent 3% of its GDP on defence in 1960. This was the start of a long decline that saw it spend 2% in 1995, then as little as 1.5% in 2015, before the wake-up call provoked by the Russian invasion of Crimea. Obviously, this upward trend is continuing, but the percentage is still below the 2% required by NATO. This is all the more important given that it conceals major discrepancies: 3.9% of GDP in Poland, 3.5% in the United States, over 2% in the other Eastern European countries, 2.1% in the United Kingdom, 1.9% in France, 1.6% in Germany and 1.5% in Italy. In 2023, the United States spent $880 billion on defence, compared with $309 billion for China and $288 billion for the European Union.

The proposals to support defence involve growing and bringing together defence companies in Europe. They are often too small compared with their American competitors, often technically outdated and more expensive, all of which means that they are not included in invitations to tender issued by European armies. This lack of industrial concentration, cooperation and homogenisation comes at a price and it is a source of weak competitiveness in an area where it is crucial.

We all know that war is on our doorstep in Ukraine and the Middle East, and that the world is nowhere near achieving peace, far from it. In Europe, albeit in (still) attenuated and fragmented forms, tensions and risks are on the rise. The problems of competitiveness we face are mirrored in the regions, the neighbourhoods and the suburbs. They are reflected in unemployment and doubts weighing on careers, not to mention violence that can always find its voice. This is why this report focuses on competitiveness, in search of a unified expression of our problems that makes it politically palatable. It combines everything that differentiates us, with the risk of pitting us against each other, whereas it is the only thing that will help Europe to reduce its shortcomings. This is why it would make no sense to strengthen Europe's competitiveness without also reducing its vulnerability to dependency and providing it with protection.

Responding to the barrage of criticism

Clearly, the Draghi report did not arrive in a serene climate. It clearly shows the weaknesses of the European Union: economic, industrial, financial, technological and so on. It begs the question of whether all the flaws in this immense and complex political organisation are reparable. Making competitiveness the unifying concept is no doubt diplomatically clever, but politically explosive. Reading the Draghi report, the European Union is almost a kind of miracle that can no longer last if its members do not unite more and in a structural way in the face of the current troubles. Without waiting for an overhaul of the Treaty, which it mentions, the report highlights the tools available to start implementing the agenda it proposes and move forward in this world in which we carry less weight.

The first volley of criticism begins with praise: what a job, what a lot to do! But then comes the comment that this is too much and that we shall not have the resources for it. These resources will be all the more insufficient in that German and Danish leaders are opposed to increasing deficits and, even more so, to issuing a common debt. As for Luxembourg, it will be said that a review of the banking and financial system is out of the question. Encouraging concentration will be all the more difficult given that the technological revolution involves a great deal of research and intangible investment, which is lost if it fails, but leads to a monopoly if it succeeds, thanks to the effects of scale. How can this contradiction be managed when a company is not a tech giant and it wants to manage competition in the traditional way?

However, some say that it is a production-oriented industrial policy, in which the ecological dimension seems to have little role to play, in which the emphasis placed on reducing standards is a cause for concern. Worse still, it is claimed to be the work of lobbyists, insufficient to solve the problems but sufficient to steer the Commission in the wrong direction. According to the Left at least, budgetary discipline has not been improved! Furthermore, and as I understand it, the word ‘trade union’ does not appear in the report, so it will take a lot to convince everyone.

In conclusion, easy criticism aside, it is question of guaranteeing peace in Europe. For this, I mostly agree with the report that we must have more growth and jobs and dare to act! We will not have a second Draghi report.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Ménégaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Amiral (2S) Bernard Rogel

—

18 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :