Member states

Maria-Christina Sotiropoulou

-

Available versions :

EN

Maria-Christina Sotiropoulou

General Manager of the European Tax Observatory

Cyprus' history has been marked by a succession of foreign dominations that have shaped its complex identity and internal dynamics. Occupied by the Ottoman Empire in 1571, the island was subjected to the so-called Millet system for three centuries. During this period, Cypriot society was structured around distinct communities, mainly Greek and Turkish Cypriots, who coexisted under Ottoman rule. In 1878, Cyprus came under British administration, ushering in an era of modernization and growing nationalist tensions. Enosis, the plan for a union with Greece, supported by a large part of the Cypriot population, did not please the United Kingdom, which opposed it first directly as a colonial power, and then indirectly by supporting the Turkish Taksim plan for a division of the island.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the Second World War, nationalist aspirations led to the independence of Cyprus in 1960, but this did not bring the hoped-for stability. Inter-communal conflicts between Greek and Turkish Cypriots worsened, exacerbated by external interference. The situation reached a point of no return with the military intervention, “Attila” in the summer of 1974, whose fiftieth anniversary deserves particular attention in view of the challenges facing the European Union. Justified by Ankara as a response to a Greek-backed coup d'état aimed at annexing the island, this invasion led to the division of Cyprus in two distinct parts and the displacement of large swathes of the population: the independent south, populated mainly by Greek Cypriots, and the Turkish-controlled north, the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in 1983 which has only ever been recognized only by Türkiye.

In 2004, the accession of the Republic of Cyprus to the European Union marked a turning point. Immediately prior to this, numerous speeches on both sides of the “green line”, were enthusiastic, even if they provided different visions of what membership of the European Union would mean politically. For the Turkish Cypriots, they wanted to believe in the end of isolation and recognition of their rights as a minority. As Elise Bernard points out, “as surprising as it may seem, twenty years ago, Recep Tayyip Erdogan supported the reunification of Cyprus, (...)”.

The younger generation of Cypriots, born in the 2000s, has only experienced Cyprus as a member of the European Union. Many express a keen interest in normalized relations and lasting peace on the island. They are often weary of the status quo of division, which they perceive as a legacy of previous generations, marked by conflicts for which they feel neither responsible nor involved. This frustration is often exacerbated by the perception that past conflicts are constantly being reactivated, preventing society from moving forward.

A notable example of this phenomenon among young people is the election of Fidias Panayiotou to the European Parliament. A young 24-year-old youtuber, he made a name for himself on social media networks thanks to his viral videos. With his particularly atypical background and lack of political experience, his election symbolizes a growing rejection of traditional forms of politics. By stating that he had never voted before, the young, elected official embodies a widespread feeling of disillusionment with traditional political parties and established institutions. This can be seen as an implicit criticism of the current political system, perceived by some as out of touch with young people's real concerns. The figures speak for themselves. Of the 900,000 potential Cypriot voters, 683,000 were effectively registered to vote in the June 2024 European elections. With turnout at 59% - up from 45% in 2019 – Fidias Panayiotou won 40% of the 18-24 age group and 28% of the 25-34 age group. For some experts, this increase in participation can be explained by the “Fidias factor”. 50 years after the division of the island and 20 years after joining the European Union, young people turned out at the polls, expressing a determination to do things differently from the way they have always known them.

All this seems far from anecdotal. When the European Parliament commemorated the 50th anniversary of the attack of July 20, 1974, Roberta Metsola declared “that in Europe, divisions have no place, it's a European issue”. She continued by recalling that “the European Union has been forged through the painful history of our continent. Where there have been wars, suffering and bloodshed, today there are meetings in a spirit of cooperation. (...) It is up to us to use this experience to bring people together and work towards the creation of a single, sovereign European state. A bi-communal, bi-zonal federation, in line with UN Security Council resolutions, Council conclusions and EU values.”

While the Cyprus question is a European matter, it is also part of a tense Mediterranean context. With an external border, Cyprus faces the same problems as Greece, Italy, Spain and Malta when it comes to managing migratory flows. Like its neighbours, Cyprus is a major gateway for migrants looking to enter the European Union – by sea or via the green line – and, in recent years, the island has seen a significant increase in the number of requests for asylum[1].

Finally, at a time when new member states with still-contested border demarcations are being considered, it is pertinent to revisit the Cyprus question, since the final positioning of the northern part of the island in relation to the European Union remains ambiguous. It is clear that, similarly, Russia's annexation of Crimea in Ukraine, Kosovo's declaration of independence from Serbia, and the secessionist movements in Transnistria in Moldavia, Donbass in Ukraine, South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia challenge the sovereignty of the states concerned and have dramatic consequences for the populations of these territories. These situations highlight the dilemmas facing the European Union as it attempts to reconcile the principles of international law with complex geopolitical realities. The situation in Cyprus provides a frame of reference in dealing with other conflicts in Europe, where questions of sovereignty, foreign intervention and ethnic minorities run up against the demands of regional security and political stability. Cyprus, like these other regions, has remained a challenge for international diplomacy for half a century, testing the limits of multilateral cooperation and the principles of international law in a context of heightened geopolitical rivalries.

I - Cyprus and European Union law

a) Protocol 10 of the Treaty of Athens: a special legal framework

Cyprus' accession to the European Union in 2004 was marked by singular circumstances, not least the division of the island following the Turkish invasion of 1974. The Treaty of Athens of April 16, 2003, which formalized the enlargement of the European Union to embrace ten new member states, included a clause that is specific to Cyprus: Protocol 10 (4 articles). The latter stipulates that the acquis communautaire are suspended in the areas where the Republic of Cyprus does not exercise effective control, i.e. the northern part of the island, occupied by the Turkish army and controlled by the TRNC, an entity not recognized by the international community.

Protocol 10 was designed to address the island's complex reality. Under this text, the application of European law in the North is suspended until a peaceful settlement of the conflict is found, in accordance with Article 1. This particular provision, a potential lever for encouraging peace negotiations, has crystallized the division of the island within the European Union. If a solution to the conflict is found, Protocol 10 would allow for the immediate application of the acquis communautaire to the whole island, making reunification a relatively smooth process from a legal point of view. Hence article 3 of this protocol and paragraph 12(29) of the conclusions of the European Council of Copenhagen of December 2002 also provide for the European Commission to propose measures to promote the economic development of the northern part of the island and to foster its rapprochement with the European Union.

b) Differentiated application of European law on the island

In the north, although Turkish Cypriots are de jure European citizens, they are excluded from many of the rights and advantages associated with this citizenship. For example, they do not enjoy freedom of movement, participation in European elections, or access to European structural and cohesion funds. This has significant socio-economic repercussions, reinforcing the economic and political isolation of the north of the island.

The European Union regards Cyprus as a single state and acts accordingly, in the hope that improved economic conditions and social interaction will eventually lead to reconciliation. Unfortunately, this zone remains in limbo. Never considered a border, but rather a ceasefire line, its condition reflects the fact that no peace treaty has ever been signed since the Turkish occupation of the north. It cannot therefore be managed as an external border of the European Union, because the whole of Cyprus is part of the Union - even though in reality it looks very much like it. The European Union sought to address this ambiguous situation by adopting, on April 29, 2004, the Green Line Regulation (GLR). Entering into force in August of the same year, it defines intra-island trade and how European law applies to this demarcation line, thus bypassing the legal problems between the two side. Two other draft regulations were proposed in July 2004: one addressed the special conditions applicable to trade with the areas of the Republic of Cyprus in which the Government of the Republic of Cyprus does not exercise effective control and the other, creating an instrument of financial support to encourage the economic development of the Turkish Cypriot community[2].

These texts appear to be primarily commercial in nature. However, given the results of the two referendums and the Greek Cypriots' rejection of the Annan plan, and following the opening of the border by the Turkish authorities, various observers suggest that the European Union has decided to offer the Turkish Cypriots compensation by easing regulations to facilitate trade and mobility. It is worth noting that, to ward off post-crisis pandemic inflation, the Greek Cypriots travelled north to buy certain products. At first, this may have been seen as a boon for trade, but unfortunately it led to an increase in prices due to demand. Inflation has been further exacerbated by the collapse of the Turkish lira, used in the north. As a result, life has become increasingly difficult for Cypriots living north of the Green Line.

c) Challenges and adaptations specific to the application of Community law

A major challenge lies in Cyprus' status as a special area within the European Union, under the European treaties. This situation requires constant adaptation to reconcile the integration of Cyprus into the European Union with the reality of a partial occupation. Thus, in a context where Turkish Cypriots are considered European citizens, despite the suspension of the acquis communautaire in the north, there are several examples of European involvement, European Union representatives, for example, with the aim of preparing the “first day” after the conclusion of a bicommunal or federal solution. This is the role that all European offices and representatives have played in the northern part of the island. From the opening of the first information point in 2002, to the establishment of the first task force in 2006, and the more recent arrival of special delegates responsible for preparing this “first day”, European efforts in the northern part have always aimed to create the legal, economic and normative conditions for accession. Indeed, this is comparable to the normative power that the European Union exercises in the neighbourhood in exchange for the promise of membership, partnership, cooperation or other relations. An examination of the procedural aspects reveals that, until recently, the actions undertaken by the European Union in Cyprus were regulated and financed under the enlargement program, even though they were formally intended for a member.

In practical terms, the presence of the European Union after accession led to the opening of an information point – in Nicosia - where citizens and businesses can find out about European standards and laws, and the requirements of the acquis communautaire. On 26 April 2004, the Council stated its resolve to “put an end to the isolation of the Turkish Cypriot community” and to “facilitate the reunification of Cyprus by encouraging the economic development of this community”. In this context, the Commission has implemented an aid program for the Turkish Cypriot community based on the (CE) 389/2006 regulation regarding the creation of a financial support tool. Turkish Cypriots thus have access to European funding to implement projects ranging from infrastructure development to the empowerment of civil society. This aid aims to bring the two communities closer together by encouraging contacts between the inhabitants of both parts of the island. Over the period 2006-2018, the European Union has allocated almost €520 million to projects in support of the Turkish Cypriot community.

The Turkish Cypriots' wish to regain their Cypriot, as opposed to their Turkish and Orientalist identity, coincided with the emphasis placed on their European belonging, traces of which can be found in the island's history. Most specialists (Hatay, Papadakis, Mavratsas) agree that a single concept of national identity has never really emerged in Cyprus, while competing ethno-nationalist concepts may have spread during the first half of the 20th century. This may go some way to explaining what Europeans in particular reproach Cyprus for today.

II - Cyprus, passports, banks and taxes

a) The golden passport program

Cyprus launched a “golden passport” program in 2013, designed to attract foreign capital in exchange for Cypriot citizenship. Thousands of wealthy investors, mainly from Russia, China and the Middle East, were able to acquire Cypriot citizenship - and by extension, European citizenship - by investing in real estate or placing funds in the local economy. This program, while highly lucrative for the Cypriot economy, quickly drew criticism from the European Union. Concerns centred on the risk of money laundering and the inadequacy of due diligence checks, which allowed individuals linked to criminal activities to obtain European citizenship. An international journalist inquiry in 2020 revealed that the Cypriot program had granted citizenship to several controversial figures, triggering a scandal that led to the program's closure in November of that year. The impact of this program on the Cypriot economy has been significant. The real estate sector, in particular, grew rapidly thanks to foreign investment, but this dependence on “golden passports” exposed Cyprus to economic risks. With the end of the program, Cyprus faced a decrease in investment and increased pressure from the European Union to reform its transparency and anti-corruption practices.

In 2019, the European Commission published a report "Citizenship and residence by investment programs in the European Union", which analyses the risks carried by these golden passport programs, particularly in terms of security, money laundering, tax evasion and corruption. It calls on member states to be more transparent, and to step up controls to prevent abuse. In October 2020, the Commission launched infringement procedures against Cyprus, as well as Malta, which was pursuing a similar program at the time. Meanwhile, the European Parliament adopted a resolution, in July 2020, calling on member states to phase out all existing citizenship (or residency) by investment programs as soon as possible.

In response to pressure from European institutions - and with the abolition of the program in November 2020 - the Cypriot government set up an independent commission of inquiry, headed by former Supreme Court President Myron Nicolatos, to investigate the program's irregularities. It appointed Demetra Kalogirou to publish a damning report[3] revealing that more than half the passports granted between 2007 and 2020 were issued irregularly or outside the established criteria. Although the program has been suspended, the Cypriot government has been working to revise the legislative framework for future citizenship and residency programs. This framework includes the introduction of stricter due diligence criteria, increased controls on funding sources and reinforced monitoring to avoid similar abuses in the future.

b) The banking sector

The Cypriot banking sector found itself the focus of international attention in 2012-2013, when the country's economy plunged into a major crisis. Cypriot banks' overexposure to Greek debt, together with inadequate risk management practices, led to a collapse of the financial system. The rescue plan imposed by the Troika (EU, ECB, IMF) was one of the most severe in the history of the European Union, introducing for the first time a “bail-in” which led to the seizure of bank deposits in excess of €100,000, mainly affecting foreign savers.

The subsequent restructuring of the banking sector led to the closure of Laiki Bank, the country's second largest institution, and the forced recapitalization of Bank of Cyprus, involving the conversion of uninsured deposits into shares. This crisis highlighted the structural weaknesses of the Cypriot banking sector, notably its excessive dependence on foreign capital and its lack of diversification. Since then, reforms have been undertaken to strengthen banking supervision and improve transparency, with efforts to bring Cyprus into line with European standards in the fight against money laundering. The government has set up an independent unit within the Central Bank to supervise banks. This unit has strengthened supervisory capacity, ensuring that banks comply with European standards in terms of capitalization, liquidity and risk management. The country has aligned its banking regulations with the international Basel III standards, which require higher levels of capital, stricter liquidity ratios, and more rigorous risk management for banks. With regard to the fight against money laundering, the country has transposed the European directives (AMLD) in its national legislation, reinforcing the due diligence obligations of financial institutions and increasing the transparency of financial transactions. Despite many measures and reforms, the Cypriot banking sector remains vulnerable, notably due to its exposure to bad debts and the persistence of an environment of weak economic growth[4].

c) Taxation

Cyprus has historically used its attractive tax regime as an economic lever, drawing in many multinational companies and foreign investors thanks to a particularly low corporate tax rate of 12.5%. In addition to this competitive rate, the country offers advantageous tax treaties with a wide range of countries, flexible rules on trusts and holdings, and a business-friendly legal framework. However, this tax advantage has brought Cyprus under the spotlight of international regulators, notably the OECD and the European Union, who accuse it of encouraging tax evasion and profit-shifting practices. In response to this pressure, Cyprus has undertaken a number of reforms to bring its tax framework into line with international standards. These reforms include the introduction of new rules against abusive practices, the strengthening of tax transparency measures and the implementation of European directives such as the so-called ATAD (Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive) directive which entered into force on January 1st 2019.

These adjustments have had an impact on the island's economic model. They have allowed Cyprus to maintain its status as an attractive financial centre while complying with demanding European standards. To compensate for these adjustments, Cyprus has sought to diversify its economy, developing financial services linked to crypto-currencies, as well as luxury tourism and weddings since the Cypriot civil status authorities agree to the civil union of couples who are prevented from doing so in neighbouring Mediterranean countries, with all the benefits that this can bring to women in terms of their rights.

III - Cyprus and geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean

a) Cyprus' strategic position

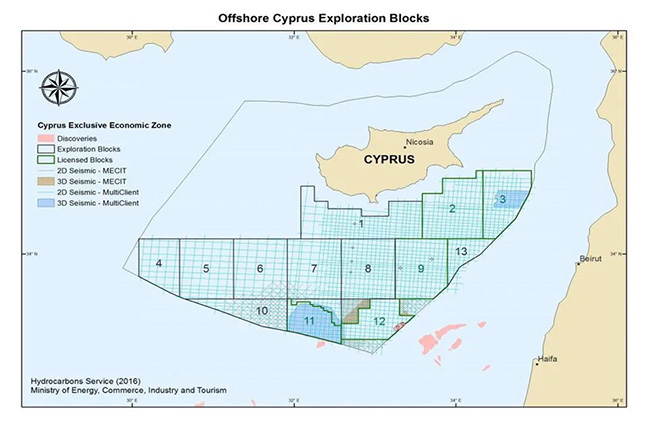

Cyprus' geographical position at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and Africa gives it considerable strategic importance. This situation was highlighted by the discovery of natural gas deposits in the Cypriot Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the 2010s, making the island a key player in the energy sector in the Eastern Mediterranean[5]. These discoveries have intensified regional tensions, in particular with Türkiye, which disputes the maritime borders[6] and is drilling in areas claimed by Cyprus. These Turkish activities have provoked several diplomatic and military incidents. As early as 2014, Türkiye stepped up its rhetoric and actions against Cypriot drilling, holding military exercises in the disputed areas to dissuade international companies from participating in Cypriot projects. In 2018, Türkiye sent the drillship Fatih, into areas claimed by Cyprus in Block 7 of its EEZ. This deployment prompted warnings from the European Union, which condemned these actions as a violation of international law, in particular the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and Cyprus' sovereign rights. Despite the warnings and the risk of Türkiye damaging its relations with the European Union, Ankara continued its drilling by sending another vessel, the Yavuz, in 2019. These operations led to the conclusions of the European Council and targeted sanctions against individuals and Turkish companies involved in drilling. Despite these sanctions and international condemnations, Türkiye maintained its drilling operations in 2020 and 2021.

Republic of Cyprus, Hydrocarbons Department, Ministry of Energy, Trade and Industry, 2016, on line

b) Relations with Türkiye and the role of the European Union

The division of the island, with the Turkish military presence in the northern part, remains the main obstacle to the normalisation of relations between Türkiye and Cyprus. ‘However, 30,000 Turkish soldiers have been stationed in the TRNC since 1974. Patriotic slogans on walls, barracks, barbed wire and sentry boxes create a militarised physical space, which affects Turkish Cypriots‘ perceptions of their own political entity’, explained Mathieu Petithomme in 2020. The accession of Cyprus to the European Union has made the situation more complex, by placing the Cypriot conflict within the framework of European Union-Türkiye relations. The European Union has tried to play the role of mediator, supporting the UN's efforts to find a bi-communal and bi-zonal solution. However, these initiatives to resolve the Cyprus question have often been hampered by the divergent interests of the Member States and Türkiye's unilateral actions, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean.

Cyprus is seeking to strengthen its alliances with other countries bordering the eastern Mediterranean, in particular Greece, Israel and Egypt, to counter Turkish actions. A notable example is the formation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, a multilateral organisation that aims to facilitate energy cooperation between these countries. The forum is seen as a counterweight to Türkiye’s ambitions in the region and a way for Cyprus to secure its energy interests by developing links with its neighbours. There is also Türkiye's role in the Black Sea, another strategic region where the recent discovery of natural gas in August 2020 is seen as a means of reducing Türkiye's energy dependence on imports, particularly from Russia[7].

It should be noted that Cyprus is no longer a factor in Türkiye's accession negotiations with the European Union. These have been frozen since June 2018, and relations between the European Union and Türkiye are essentially based on ‘give and take’ in terms of migratory flows and border security.

c) Cyprus in the context of European security

Cyprus' strategic position in the eastern Mediterranean makes it a key player in European security, despite it not being a member of NATO[8]. The island is home to two British military bases, Akrotiri and Dhekelia, which are crucial to British military operations and those of NATO allies in the region. These bases have played an important role in recent operations, such as the interventions in Syria and Iraq, and are essential for the surveillance of the Levant region. Cyprus participates actively in the security initiatives of the European Union, notably within the framework of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The country has contributed to several missions, including peacekeeping operations in Africa and maritime surveillance missions in the Mediterranean. Cyprus is also a key partner in the fight against terrorism and organised crime in the region, working closely with other Member States and third countries[9].

On a regional level, Cyprus is facing the challenges of migration in the Eastern Mediterranean. The island is a transit point for migrants and refugees from the Middle East, particularly Syria, and must manage these flows while ensuring the security of its borders. The complex geopolitical situation in the region, marked by the conflicts in Syria and Libya, adds a further dimension to the security challenges that Cyprus has to overcome.

To manage these risks, Cyprus has strengthened its relations with its neighbours, notably through bilateral agreements and regional forums. One example is the trilateral agreement with Greece and Israel, which covers areas such as energy security, military cooperation and crisis management. This type of partnership illustrates how Cyprus is seeking to position itself as a stabilising player in the Eastern Mediterranean, while navigating an increasingly complex geopolitical environment.

IV - The European Union and its neighbouring powers - the Cypriot perspective

During its first six-month presidency of the Council in 2012, the subject of the island’s division was omitted from the issues that Cyprus chose to highlight. Was the separation of the Turkish-Cypriot problem from its responsibilities and obligations as holder of the Presidency of the Council of the Union a political choice of neutrality? Negotiations between the two communities under the auspices of the United Nations were effectively postponed during this period, and Cyprus aimed to ensure its neutrality at the time of enlargement, precisely because of the Turkish question and the deterioration in relations between Türkiye and the European Union. The Presidency defined four major strategic priorities designed to work towards a more efficient Europe, contribute to growth and lay the foundations for a more prosperous and socially cohesive European political system based on the principle of solidarity.

In 2024, the division of the island is still not a topical issue, and no government seems ready to make a political choice, preferring endless negotiations to a possible reunification in which they would not find their interests satisfied. However, circumstances are such that the subject of division must return to the negotiating table, and it is pertinent to ask whether this model should be applied as such to future enlargements of the European Union. Indeed, the process of European integration is strategic both in that it influences political decision-making and in that it creates a set of norms and values as well as a shared European identity. The enlargement process implies a redefinition of the European Union's external borders and, consequently, an ongoing reshaping of the neighbourhood, which is affected by processes of integration and association, cross-border cooperation and specific policies. When considering Ukraine's accession, it is easy to transpose the Turkish-Cypriot situation to that of Crimea and Donbass, since all of these territories share similar characteristics linked to disputed sovereignty, foreign intervention and implications for regional security.

The European institutions have supported a position in favour of the reunification of Cyprus and have denounced actions that jeopardise this prospect. Europe has always called for peaceful dialogue based on United Nations resolutions and has emphasised its role in supporting efforts to achieve a just and lasting solution. The UN has been present in Cyprus since 1964, making it one of the longest-standing peacekeeping missions (60 years).

It seems that Cypriot leaders are concentrating on business as usual so as not to be held responsible for the impasse. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres is making a sincere effort to promote the resumption of negotiations, but the mood is not particularly favourable.

The international community has other priorities and interest in the divided island has waned. The European Union is focusing its attention on the war in Ukraine, because it feels threatened by Russian revisionism. The United States has tacitly accepted the situation in Cyprus because it does not affect vital American interests. Türkiye will only change its policy towards Nicosia if it is really under pressure or convinced that it will achieve major progress. Neither is likely to happen in the near future. Nor is there any force that will exert pressure on Ankara to reverse its maximalist positions, or anything tangible to offer in exchange, such as membership of the European Union, for it to adopt a constructive stance.

***

On the 50th anniversary of the invasion of the island, the former finance minister of Cyprus, Harris Georgiades, made a bold proposal in his book "The New Realism"[10]. Instead of setting expectations too high, it would be better to try to negotiate step by step with Ankara when conditions allow for it. Without illusions or defeatism, the Greek side can take initiatives with a view to mutually beneficial negotiations with Türkiye. No one claims that this effort will be easy. According to Harris Georgiades, "Half a century after the Turkish invasion, it is time for a new, realistic approach. It is not enough to proclaim our positions and invite the Turkish side to dialogue. Of course, cheap and irresponsible rhetoric, which ignores reality and the passage of time, will get us nowhere either. We need to take a sober look at the facts, get a clear picture of Türkiye's ambitions and assess both the risks and the options open to us".

[1] In relation to the population of each EU country, Cyprus recorded the highest number of first-time asylum seekers in 2023 (13 first-time asylum seekers per 1,000 inhabitants), ahead of Greece and Austria.

[2] The 1st regulation - Direct Trade Regulation - encountered major obstacles and was never effectively applied. The main reason was opposition from Cyprus, which feared that this measure would legitimise the north of the island. As a result, although this regulation was proposed by the Commission in 2004, it was not adopted by the Council. The 2nd regulation providing for a financial instrument has been partially implemented. The Union has provided financial assistance to the Turkish Cypriots. However, this does not represent full or equivalent support to that which could be offered in the context of direct trade between the European Union and the northern part.

[3] Kalogirou Report, available in Greek.

[4] Several official reports describe the banking and financial reforms undertaken by Cyprus: Central Bank of Cyprus. (2015). Annual Report 2014. Nicosia: Central Bank of Cyprus ; International Monetary Fund. (2013). Cyprus: First Review Under the Extended Arrangement. IMF Country Report No. 13/293 ; European Commission. (2014). The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus - Fourth Review. European Economy. Institutional Papers. ; OECD. (2017). Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes: Cyprus 2017 (Second Round).

[5] In particular: the discovery of the Atoll (or Aphrodite) in 2011, in block 12 of the EEZ, by the American company Noble Energy, in collaboration with the companies Delek and Avner. This field is estimated to contain between 130 and 200 billion m3 of gas; the discovery of Hadrian in 2013, in Block 12, which has boosted estimates of gas reserves; and the discovery of Onasagoras in 2019, in Block 6..

[6] Türkiye is not a signatory to the Montego Bay Convention, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

[7] Indeed, nearly half of its gas comes from Russia, via the Turkstream pipeline, which runs under the Black Sea. The country has become Gazprom's second largest customer, and for several years now Turkey has been trying to diversify its sources of supply.

[8] Cyprus is not a member of NATO. The division of the island is the main reason for this, combined with Türkiye's veto on possible Cypriot membership.

[9] Some examples of collaboration with member states or neighbouring countries: The creation in 2014 of the Cyprus-Greece-Egypt Tripartite Forum with annual meetings alternating between the member countries to discuss regional security issues; participation in EUROPOL actions such as the maritime security cooperation programme, which has modernised Cyprus' maritime surveillance capabilities; participation with FRONTEX in 2022 to help monitor maritime and land borders and combat cross-border crime; participation in security operations, such as "Irini" in 2020 (successor to operation "Sophia") which aims to end to illegal trafficking in the Mediterranean and has included contributions from Cyprus, such as patrols and control operations at sea.

[10] Harris Georgiades, Le nouveau réalisme : Le sujet chypriote 50 ans après l’invasion turque, 2024, Editions Papazissi, Athènes, Χάρης Χρ. Γεωργιάδης, Νέος ρεαλισμός: Το Κυπριακό 50 χρόνια από την τουρκική εισβολή, 2024, Εκδόσεις Παπαζήση, Αθήνα

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :