Agriculture

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

SUVs versus limousines? Cows, not cars! What if agriculture, and livestock farming in particular, were the adjustment variable in international trade negotiations being conducted - discreetly - by the European Union? What are we to make of the much-heard argument raised at the agricultural blockades?

I - Agriculture in trade negotiations

A - Historic milestones

1 - Economic history

This choice - agriculture versus industry - goes back a long way. It was central to the Ricardo’s “Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” which, in 1817, described the advantages of specialisation as the basis of international trade. While it goes without saying that it is in a country's interest to produce goods for which it is more competitive than others, Ricardo shows that even if country A is less efficient than country B, it is in each country's interest to specialise in what it produces more easily (country B) or with the least difficulty (country A). The resulting trade is beneficial to both. Ricardo illustrates his theory of comparative advantage with cloth and wine: Portugal is better at both, but England is less disadvantaged in the case of cloth and must therefore specialise in this area. Wine for cloth. Is this so very much different from trading cars for cattle?

2 - The Common Agricultural Policy hit by multilateral trade negotiations

The European Union's openness to international trade is enshrined in the Treaties. The GATT (1947) also covered agriculture, but in practice this sector was excluded from the scope of the negotiations. Behind the argument of the food imperative, the United States and Europe wished above all not to modify the massive support already devoted to agriculture. But pressure from emerging countries overcame this resistance. Once the internal market was virtually complete, the time came to push the European Union into the deep end of international trade. Whatever the cost. This happened in the early 1990s. It was a time of major multilateral negotiations, and European agriculture and its organisation, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), were the obvious targets. At the time, the CAP was a caricature of protectionism, with adjustable customs duties (agricultural levies) and export subsidies (refunds). Both systems were dismantled in the Blair House (1992) and Marrakesh (1994) agreements, in parallel with the major reform of the CAP in 1992. The shift from price support to direct income support was an immediate consequence of the integration of agriculture into international trade.

3 - The time of bilateral negotiations

The time for multilateral negotiations has passed. Bilateral negotiations have taken over. A trade agreement provides a privileged framework for trade, reduces customs duties, increases import quotas, simplifies procedures, organises equivalence, regulates investment and opens up public procurement markets. In the absence of an agreement, customs duties are set unilaterally by each party. The European Union has deliberately committed itself to concluding bilateral agreements. By 2020, it had a network of 40 trade agreements covering 72 countries. Over the past eight years, negotiations have been concluded with Canada (CETA), New Zealand, Singapore, Vietnam, Kenya, Mexico, and Chile. Others are underway with Indonesia, India and Mercosur (Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay and Argentina). In all cases, agriculture is a component of the agreement.

B - Agriculture, just one of the issues in trade negotiations

1 - The negotiation procedure

Trade policy is one of the Union’s exclusive competence. Negotiations are conducted by the Commission, but it is granted authorisation by the Council (ministers), which issues negotiating directives. The agreement is signed by the Commission following a Council decision. It takes effect following a "decision to conclude the agreement" (equivalent to ratification under national law) adopted by the Council after approval by the European Parliament. But it can also be applied on a transitional basis by decision of the Council. Other than in exceptional circumstances, Council decisions are taken by qualified majority. Negotiations are highly opaque. The negotiating directives are not public — with a few exceptions (such as in the case of mixed agreements[1]), and national parliaments are not involved in the procedure[2].

Why aren't the negotiating directives made public? The official reason is not to reveal lines of defence and points of interest to the opposing party. This goes on throughout the negotiations. The Commission does not want to be embarrassed by differences between Member States. Member States are kept in the loop by the Trade Policy Committee, which meets weekly. France, in particular, has enough trouble finding a common position without being embarrassed by additional recriminations from specific industries or sectors. All in all, the negotiations are conducted with great discretion. But in the end, there is a sense of dispossession — dispossession by technocracy — and this can only lead to rejection.

2 - The diverging interests of States

The Commission negotiates on behalf of the European Union but it has to deal with the divergent positions of the Member States. The negotiations bring into play the offensive and defensive interests of each country. Agriculture is as much a part of the negotiations as anything else. Export-oriented countries (Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands) as well as large companies with access to public contracts (water, sanitation, transport) are interested in trade agreements. Conversely, some countries seek to protect certain sectors or specific features, such as protected designations of origin, which have been undermined by commercial practices abroad. France and Italy often have similar interests in this respect. For this reason, trade negotiations have been described as "an arbitration between Mercedes and Saint Nectaire". Agriculture often seems to be used as a “bargaining chip” in a multi-stakeholder negotiation.

3 - The long process of negotiation

Negotiations generally take between five and ten years (and as long as twenty in the case of Mercosur) to complete, given the detail and precision of the provisions in sensitive areas (see below) — with no guarantee of success. Trade negotiations with the United States and Australia were suspended before an agreement could be reached. The agreement can also be applied on a transitional basis but does not become part of European law until the Council has taken a decision. Member States can then oppose it. However, it is always difficult to maintain the position of an isolated State in the long term for reasons that the others consider to be insignificant. The European Parliament can also refuse to give its assent, as it did in 2012 for a project on counterfeit goods, but this was an agreement of limited scope. Opposition can also come from national parliaments in the case of a mixed agreement (a combination of European trade provisions and provisions under national jurisdiction). This was the case with the CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement) before a compromise was found, by splitting the trade agreement in two. The Court of Justice confirmed (opinion 1/17 of 30 April 2019) the classification as a mixed agreement.

II - Agriculture, a subject unlike any other

A - The particularities of agricultural negotiations

1 - The negotiation framework

The parties start by setting limits - collective preferences - on the issues that will be excluded from the negotiations. In agriculture, for example, there is never any question of importing chlorine-treated chickens or hormone-treated beef. These are both outside the scope of the negotiations. The parties also define the sensitive products that deserve special attention. In Europe, livestock, especially cattle, is one of these products.

2 - Agricultural issues are often at the root of disputes between parties

Every negotiation has its moments of tension, but no sector appears to be as contentious as agriculture. Concessions are bilateral. The most controversial issues are the safeguarding of protected designations of origin and the opening up of markets. The European Union defends the principle of protected designations, but abroad it is often the case that names have become generic. In America, for example, Comté or Munster are simply production methods, just like any other. In 2023, negotiations with Australia floundered over Prosecco and Feta, which are used by local producers. The proposed agreement with Mercosur recognises 350 PDOs/PGIs. Access to the partner's market is crucial. In 2023, Australia asked to benefit from the same duty-free export quotas as Canada regarding beef production.

3 - Deep differences between sectors

The risks associated with international competition vary greatly from one sector to another. The opening of a foreign market can be an opportunity for certain sectors: cheese and wine, for example, almost always benefit from trade liberalisation. Even within the same sector, interests are far from uniform. The beef sector could be threatened by imports, while the pork sector, dominated by Germany and Spain, is well placed to develop its exports. Similarly, the agri-food industry — often multinationals — is interested in imports of cheap raw materials, including meat, which allows them to cut costs in the production of ready meals. Trade negotiations bring out the full diversity of farming systems and actors in the sector.

B - The traditional weapon of tariff barriers

1 - The tariff-quota duo

The removal of trade barriers is a well-understood issue that does not present methodological problems (unlike non-tariff barriers, which are more difficult to understand and address). The most basic measure to protect a single market is to impose import barriers. Either in the form of fixed tariffs (X amount per tonne) and/or proportional tariffs (as a percentage of value), or in the form of quantitative restrictions (import quotas). These two levers are widely used in the agricultural sector. Tariffs can be high, exceeding 30% or even 50%. A practice known as "tariff peaks" is common in Europe: this is the case for dairy products, sugar and meat. Prior to the CETA agreement, Canada also applied tariffs of between 10% and 25% on agricultural products, and up to 227% on cheese. At this level, the elimination of tariffs is a very important issue for both the exporter and the industry concerned.

The impact of tariffs is mitigated by the associated practice of quotas. Quotas mean that a certain quantity — a quota — can be imported duty-free or at a reduced rate of duty. Beyond the pre-determined quantities, normal tariffs apply. This practice is widespread. Opening an import quota at zero or reduced duty is a common practice in trade relations, a gesture of openness in the context of preferential agreements[3] or of appeasement in a situation of conflict. Negotiations are extremely detailed in nature. For example, the EU-Canada agreement provides for total tariff elimination (sugar), partial elimination within a quota (pork and beef), but maintains tariffs on poultry. Tariffs and quotas are set by type of product (fresh meat, frozen meat, etc.) and vary by cut (whole, carcass, boned, fat, etc.). Tariffs can be phased out immediately or over a number of years. These details illustrate the complexity of bilateral negotiations.

2 - The sometimes highly political use of the tariff weapon

Without a bilateral agreement, setting tariffs is a unilateral decision. Sometimes with a strong political background. Tariffs can be raised in retaliation. The United States is no stranger to this. In several disputes with Europe, the US administration has chosen to raise tariffs on certain agricultural products. This was the case in the dispute over hormone-treated beef (2009), over government support for Boeing/Airbus, over aluminium and, most recently, over the taxation of the GAFA. In all these cases, some products have witnessed massive tariff increases (wine, cheese). A case in point is Roquefort cheese, which has been subject to a 100% import tax into the United States since the dispute over hormone-treated beef, and was threatened with a 300% tax during the GAFA dispute!

Conversely, tariffs can be abolished to help a country. This has been the case since 2022 in relation to the war in Ukraine: in May 2022, the European Union suspended tariffs on Ukrainian poultry to support the country's economy. The trade agreement was extended for another year in June 2023. These imports are not subject to quotas. The commercial impact was immediate, with poultry imports rising from 10,00 to 25,000 tonnes per month. With this measure, the economic area was transformed into a subject of political debate both within industry and in parliamentary assemblies.

C - The beef industry, a weak link in trade negotiations

The beef sector is classified as a "sensitive sector". There are several reasons for this sensitivity. Beef is still very much protected by high tariffs (55% when fixed and proportional tariffs are combined). The European market is protected even though beef is the most exported meat in the world (10% of world production). Some countries have made it a speciality, such as New Zealand, which exports 89% of its production, and several Latin American countries linked by a specific trade agreement.

Trade agreements lead to the adoption of import quotas[4]. None of them, taken individually, is likely to seriously disrupt a single market. However, there are two problems with this measure.

The first is the accumulation of quotas. At European level, quotas are still very low. For beef, for example, until the planned agreement with Mercosur, none exceeded 50,000 tonnes (out of a European market of 6 million tce). The quota with Canada represents less than 0.6% of European consumption. But even limited quotas add up. This accumulation cannot be ignored.

The second is related to opening up to countries that are sometimes very competitive. While the difference in competitiveness between Canadian livestock farms and those in Europe has been estimated at nearly 10%, the advantage can rise to 40% in the case of American farms, or even 100% in the case of Brazil (economies of scale and pasture fodder). This double movement, in terms of volume and price, can only lead to the emergence of foreign competition from outside Europe. Even a modest breakthrough in a market in decline both in terms of production (with decapitalisation of the herd) and consumption (individual consumption has fallen by 1kg in four years) represents a real challenge for the European beef industry, particularly in France.

III - An attempt to evaluate trade agreements

A - Preliminary assessment of the application of the CETA

In most agreements, public debate focuses on livestock farming. The application of CETA is a good example of this.

1- Strong growth in trade

98 % tariff barriers have been removed. EU-Canada trade has grown significantly since 2017, when the trade agreement was implemented: +50% in trade in five years, twice as much as the Commission had predicted. There is clearly a "CETA effect".

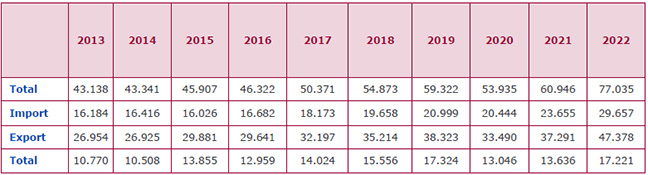

EU-Canada trade 2013-2022 (€ million)

Source: Commission, DG Trade European Union

The results vary considerably from one sector to another. Although the industrial sector is the main beneficiary, the agricultural sector has benefited greatly from trade liberalisation agreements.

In addition to CETA, the Commission has quantified the impact of the last ten trade agreements concluded or under negotiation by the European Union. It estimates that "the value of EU agri-food exports in 2032 is estimated to be between €3.1 and €4.4 billion higher than without these ten trade agreements, while the value of imports is estimated to be between €3.1 and €4.1 billion higher. This implies a balanced increase in exports and imports and a slight increase in the overall trade balance of the Union." The results vary from sector to sector. It is difficult to draw an overall balance, as the results vary from one product to another. For example, while the CETA agreement has increased the potential for duty-free Canadian beef exports by a factor of 3.5, it has tripled European pork exports to Canada in four years. Europe exports 100 times more pigs to Canada than in imports.

2 - The beef issue

The CETA agreement increases Canada's duty-free beef export capacity to Europe by a factor of 3.5[5]. However, the agreement has not led to a flood of imports. There are several reasons for this restraint.

Meat exported to Europe is not the same as meat produced in Canada. To enter the European market, beef from third countries must meet certain health requirements: no use of growth hormones (common in America), slaughter in an EU-approved abattoir (five approved abattoirs in 2018), compliance with certain health requirements (listed carcass decontamination procedures). These rules are subject to change. While the absence of hormones has been confirmed, the use of antibiotics and veterinary supplements, which are not prohibited by the Agreement but have the same effect as a growth hormone, remains unclear. The regulation 2019/6 11 December 2018 prohibits the use of antibiotic growth promoters. This provision applies to Canadian meat by virtue of the principle of mirror clauses, i.e. the applicability of European rules in this area to imports.

These rules require the establishment of a separate channel for European exports. This cost limits the competitive advantage gained from economies of scale in intensive production and fattening in feedlots with tens of thousands of animals. "The competitive difference in favour of Canadian meat (10%) is potentially offset by the need to comply with European health requirements.” Slaughter conditions in giant abattoirs are also a competitive advantage that is eroded by European constraints[6].

Under these conditions, the breakthrough on the European market can only be gradual. Canadian beef imports have multiplied by a factor of 3.5 but remain below the authorised quotas. In 2023, meat imports rose by 3% (America), 7% (Argentina) and 15% (Brazil).

For France, non-European imports are marginal, this represents just 3% of beef imports, or 0.5% of consumption. But these aggregated figures hide the anguish felt by farmers. In reality, competition is taking place in micro-segments of the market, particularly for the most profitable premium cuts. But even if this imported competition is weak, it is still perceived as a threat.

B - Lessons to be learned

In general, no trade agreement radically changes a market. However, no agreement seems to succeed in the media test without encountering increasing difficulties.

1 - Certain procedures deserve special attention

At European level, the practice of provisional application adopted by the Council raises questions. What is the role of the European Parliament, which must give its assent before the agreement is concluded, when the agreement has already been in force for a long time? It is certainly not easy to take responsibility for rejecting an agreement that has taken five or ten years to negotiate. Parliament managed to impose minimum information provided by the Council[7] and develop the beginnings of an independent evaluation. But there is room for improvement. A path supported by the Commission - how can anyone oppose it? Why not involve MEPs when the Council defines the negotiating mandate? The extreme opacity of the negotiations can only lead to suspicion.

At national level, it should be possible to provide regular information to the European Affairs Committee of each assembly, which is responsible for monitoring the progress of the negotiations. There is no technical monitoring of the negotiations. Member States follow the progress of the Commission's negotiations through the trade policy committee (TPC). In other words, it is as if the practical difficulties were only discovered at the last minute, after the agreement has been signed!

2 - Recognising the limits of trade agreements

The first limitation lies in the failure to take into account the environmental impact of the agreements, whether in terms of calculating carbon footprints or greenhouse gas emissions[8], or the perverse effects of specialisation (deforestation). It is true that in the twenty years since the Mercosur agreement was negotiated, these issues have become increasingly prominent in public debate. But any agreement must be examined through the prism of current priorities. This also applies to European food sovereignty, the latest flagship of European policy.

The second limitation is the difficulty of controls. Despite the efforts made, the health checks carried out and the progress made with the mirror clauses, certain practices remain uncontrolled: animal feed (grasses, GMOs, meat-and-bone meal), animal welfare, transport conditions and times, etc.

The third limitation concerns the ineffectiveness of the safeguard clause. The provisions of the trade agreement, in particular quotas or tariff exemptions, can be suspended ("withdrawn") if the European Union activates the safeguard clause. This clause is provided for in trade agreements, but can also be triggered on the basis of the regulation 2019/287. It can be triggered by the Commission at the request of a Member State if the Commission considers that a product is being imported into the Union "in such increased quantities [...] that serious damage is being caused or is likely to be caused to producers in the Union". This instrument is rarely used in the agricultural sector. Both the conditions of implementation (given the small size of the quotas) and the lack of political will make this measure of little use. Requests to limit Ukrainian exports of agricultural and poultry products to the EU are an example of these difficulties.

C - Restoring credibility

So many shortcomings affect public confidence. European and national institutions would be taking a major risk if they failed to address these issues.

1 - Restoring coherence

This is the main criticism of trade agreements. The European Union has chosen openness. The effects of opening economies to international competition are generally positive. Globalisation boosts competitiveness and offers prospects for growth and jobs. But "free trade agreements are the death of agriculture" is often heard at farmers' roadblocks. In reality, only a sector-by-sector analysis can provide a credible assessment. Any regulatory proposal must be backed up by an impact assessment. But these are largely lacking. The difficulties in analysing the impact are obvious, but these studies are often carried out by private companies who "refuse to be too critical in their work for fear of not being called upon again later".

While the Green Deal will reduce production more or less (in line with the "end of the production model"), trade agreements will increase imports. But where is the coherence between the reduction in milk production and the increase in imports of New Zealand milk powder?

2 - Avoiding naivety

The fragility of certain sectors is obvious. We should prepare for this. Ultimately, what will consumers decide? Preserve domestic producers or look at prices on the shelves, driven down by imports? Even with the tarnished image of feedlots, i.e. feedlots holding several thousand animals[9]. Germany, for example, is the biggest importer of beef. We have to recognise that German consumers, despite their sympathy for French farmers, have little reason to favour French meat when it could be imported more cheaply from Argentina. The choice is no longer between Mercedes and Saint Nectaire, but between Charolais from Saône-et-Loire and Angus from Patagonia. This does not put France in an easy position.

Behind the trade agreements, there are also considerable strategic issues at stake. The agreement with Mercosur certainly threatens the beef industry. The agreement with Chile has similar consequences. But as Members of Parliament have pointed out, these South American countries have some of the world's largest reserves of copper, lithium, cobalt, nickel and silicon, resources that Europe lacks. These are all useful resources for current and future technologies (wind turbines, electric batteries, semi-conductors). Not to mention China, already Brazil's biggest trading partner, which sees Europe's difficulties as no bad thing. For these countries, in the event of repeated obstacles to the application of these agreements, the alternative will soon be found.

3 - Supporting vulnerable sectors

One of the criticisms that can be levelled at European intervention, and particularly at the Commission, is the idea that a reform can only be successful if it provides guidance and help. Reforms would be better accepted as new constraints if alternative solutions were offered. This is particularly true in the agricultural and environmental fields. Abolishing glyphosate and synthetic pesticides is one thing, but proposing something else is another. Tax off-road diesel (this was the starting point for the road blockades in several European capitals!) but encourage the development of electric tractors powered by solar panels on the farm, for example. Without proper support, the Green Deal is understood by the agricultural world as a form of punitive ecology devised by out-of-touch civil servants, leading to a downward spiral of production.

It seems necessary to provide budgetary support to offset the disruption caused by trade agreements. The European Union has done this in the industrial sector with the world globalisation adjustment fund — on the grounds that globalisation can have "negative effects on the economic context" — when we are talking about jobs and professions. The Commission's lack of foresight is regrettable. This fund is intended to redeploy workers who have lost their jobs "as a result of major changes in international trade". Aid was reserved for mass redundancies. A revision of the regulation to extend the scope of the fund to cover the consequences of trade agreements on agriculture would be both simple and useful for the creation of short supply chains or chains connecting farmers and restaurateurs.

Finally, is it possible to imagine the emergence of genuine professional solidarity? It is clear that the results of trade agreements vary considerably from one sector to another. Some are weakened, but others benefit, and in two ways. Firstly, by saving on import duties. The reduction in customs duties on entering the Union, the only real resource of the European budget, is offset by increased recourse to national contributions deducted from national resources. In this way, what used to be borne by importers and industrialists who had to pay customs duties is now borne by taxpayers. Second, trade agreements offer development opportunities. "The opening of these export quotas to Canada has led to a 57% increase in French cheese exports between 2016 and 2022.”[10] Is it naive and irresponsible to imagine a sharing of values? Solidarity between sectors? And, why not, between producers, who have benefited from the opening of export markets, and farmers?

In 1999, when the US government imposed the first 100% tax on Roquefort cheese, sheep farmers and breeders were supported by the dairy interprofessional organisation (mainly cow's milk)[11]. It was a symbolic gesture, but one that showed a form of solidarity.

The author would like to thank Elena Kunkel, Research Assistant at the Foundation.

[1] A mixed agreement brings together subjects that come under trade policy stricto sensu and subjects that come under national competence, such as the investment protection regime. However, inserting such clauses into trade agreements would not guarantee the involvement of national parliaments. In the light of experience with the CETA, the Commission has decided to split the trade agreement into two parts. 99% of the agreement will remain under the exclusive competence of the EU.

[2] A senator who had taken an interest in the CETA agreement said that he had been allowed to look at the documents (several thousand pages in English), alone (without an administrator), without the possibility of taking photographs and under the surveillance of a security guard.

[3] For example, the agreement with Morocco.

[4] Regulation 593 of 21 June 2013

[5] The duty-free quota will rise from 19,110 tce before CETA (Hilton and national quotas) to 64,950 tce after CETA from 2022.

[6] Regulations require compliance with hygiene and microbiological criteria, a cleaning and disinfection procedure, etc…

[7] The Council informs Parliament at each rotating presidency of the progress of negotiations. (This is an informal arrangement concluded in 1973 known as the "Luns-Westerterp" procedure).

[8] CO2 emissions linked to trade accounted for a quarter of total global emissions.

[9] In Canada, the giant JBS slaughterhouse in Brooks, Alberta, processes 4,000 head a day and is associated with a feedlot of 70,000 head.

[10] Export quotas increased to 17,700 tonnes at EU level by 2022.

[11] Roquefort producers managed to reduce their costs by taking money from the promotion budget, and this budget was offset to the tune of €7 million by aid from the Office National Interprofessionnel du Lait (ONILAIT)

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :