Future and outlook

Yves Bertoncini

-

Available versions :

EN

Yves Bertoncini

Consultant in European Affairs, Lecturer at the Corps des Mines and ESCP Business School

1. What kind of convergence for "European defence?”

1.1. A stronger European defence toolbox

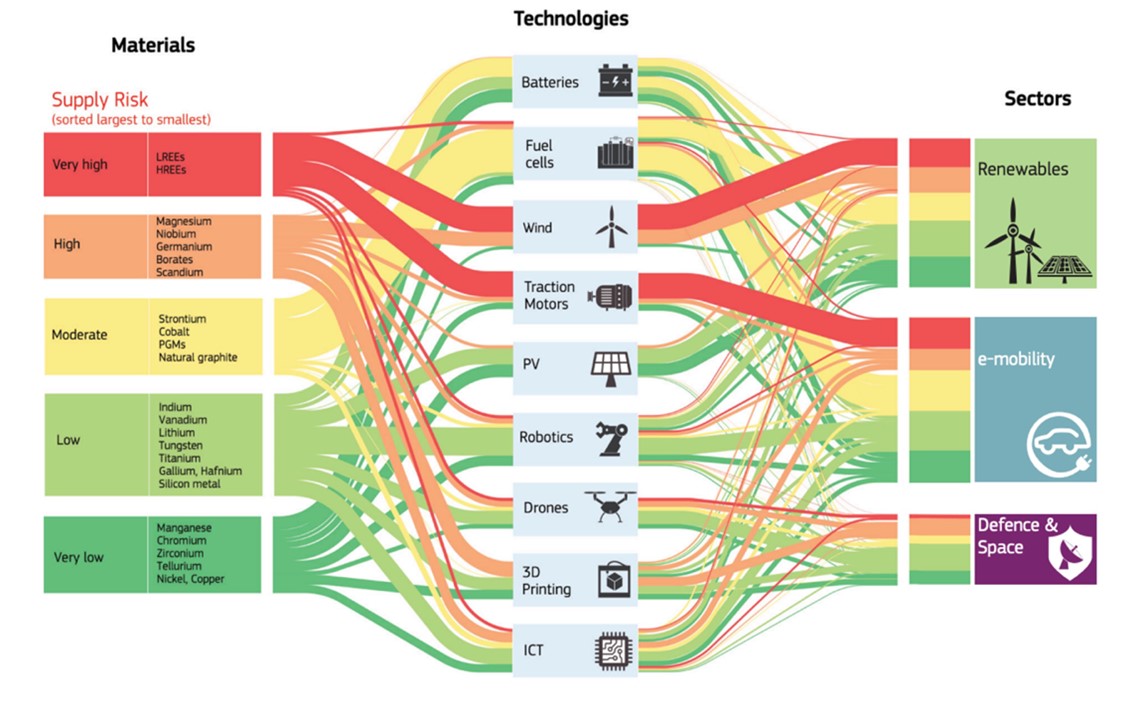

Table 1 : Common European financial efforts in defence 2021-27 (€ billion)

Source: Council and European Commission, author's calculations, Yves Bertoncini

(1) 1.5 billion may be added via the “Step” initiative

(2) For the period 2022-2024

1.2. The imperative need for defence "convergence criteria”

Recent progress on doctrinal and capability issues bears witness to a salutary new awareness of the need to strengthen the defence of the European Union and its Member States, which has been heightened by Russia's aggression in Ukraine. This wake-up call is reminiscent of the one provoked by the Korean War, which gave rise to the "European Defence Community" project, the rejection of which in France led to German rearmament within NATO. Although history rarely repeats itself, the substantial strengthening of European defence must now, more than before, be based on a major effort to achieve strategic, operational and political convergence between Member States - since the addition of disparate tools cannot take its place[9].

Firstly, strategic convergence: at a time of war in Ukraine, European defence against Russia bears one name only: NATO. Given that the defence of Europe is not limited to the military threat posed by Russia, this crude observation should not, of course, preclude the strengthening of European defence for other purposes (from space warfare to terrorism and cyber-attacks). It should, however, serve as a reminder that it is to the United States and its enormous military and strategic capabilities that Europeans and Westerners turn when they are threatened by large-scale enemies - this is as true at the time of the attacks on Ukraine as it was when Australia renewed its submarines in response to China. This transatlantic tropism will persist as long as Europeans are in the process of achieving the same military level, i.e. in the medium term. Until then, strengthening "NATO’s European pillar" to provide greater support to the defence of our continent is a code name that will open far more wallets and minds than an uncertain "strategic autonomy", perceived as anti-American, and therefore repugnant, in most Member States[10].

It is also on the basis of operational convergence that European defence sovereignty has a chance of really growing, over and above the resolute and increased mobilisation of the tools mentioned above (EDF, EDIRPA, ASAP). On this second point, the major armaments programmes must be the focus of the greatest cooperation efforts, such as those dedicated to the combat aircraft of the future (SCAF), the combat tank of the future (MGES) or the "euro-drone": this presupposes a very complex and often contentious sharing of sovereignty, which must be fair and mutually beneficial for all willing countries. There is an urgent need to strengthen and broaden this industrial pooling so that it can reap the full benefits of growing defence budgets, unless we want to continue selling off "national flagships" that are too expensive and likely to be abandoned for their American competitors - the latter logically and by default continuing to be preferred in the short term.

Finally, the advent of European sovereignty in defence matters requires significant political and institutional convergence between Member States. With most Member States devoting 2% of their GDP to defence, it is the definition of the conditions for the use of force that will determine the practical impact of the resolutions arising from the war in Ukraine. This pre-supposes that decisions relating to defence - from arms exports to external military intervention - are subject to adequate political and public control. In this respect, there is a huge gap to be bridged between the discretionary power of French Presidents, who are free to send troops abroad without a vote or debate in the National Assembly - at the risk of going it alone - and the rather strict parliamentary control practices in force in other European countries. The adoption of the "Strategic Compass" should also encourage joint reflection on the conditions for the use of military force and external intervention, given that the most recent experiences have seen their effectiveness challenged, from Afghanistan to Libya, not forgetting the Sahel.

All in all, the European security revolution in the making is similar in scale to the one that led to the introduction of the euro in response to the geopolitical upheaval brought about by the fall of the Berlin Wall, thanks to the Maastricht Treaty: it will only be possible to fulfil the promises of this Treaty in terms of collective security and those generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine if new "convergence criteria" are defined and respected in strategic, industrial and political terms. It is important for each Member State to play its full part in this endeavour, whether it is in a position of leadership, like France, or lagging behind, like Germany - unless it opts by default for the exercise of national sovereignty, which seems less and less capable of effectively meeting current and emerging security challenges.

2. Reducing Europe's energy dependency?

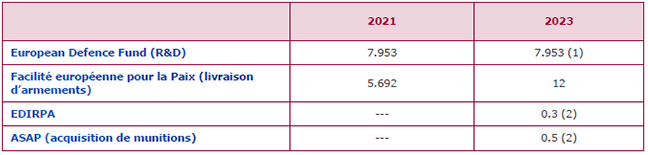

Another priority of the "Versailles Declaration", the assertion of greater European sovereignty in energy matters consisted first and foremost of dramatically reducing Europe's dependence on Russian hydrocarbons, in particular through the “Repower EU” plan (Graph1). Deepening this process requires a profound ecological and political transformation of the European development model, capable of freeing itself from hydrocarbons. This would also be encouraged by a calming of the heated debate regarding the choice of alternative energy sources, which remains a question of national sovereignty, but which at this stage is burdened by an ideological dispute over nuclear power.

2.1. The "Repower EU" plan: three highly complementary components

The energy realignment undertaken at Versailles has been achieved through a forced diversification of European sources of supply, one of the three strands of the “Repower EU plan”. For example, Europeans have turned more towards Norway, the United States and Qatar for gas, in a context marked by a sharp rise in prices, but also by the prevalence of the objective of securing supplies. In terms of sovereignty, the only merit of this diversification is that it puts an end to excessive dependence on a single partner, and therefore reduces Europe's strategic vulnerability. The same applies to doubling the use of liquefied natural gas (from 20% to 40%), which is easier to substitute than gas delivered via pipelines. Inspired by the experience of joint purchasing of vaccines against Covid-19, the new private platform for the aggregation of requests and joint purchasing of gas (“Aggregate EU”) will give willing European companies greater market power to negotiate better prices with international suppliers - if not reduce their dependence.

Graph 1

“Repower EU” Plan and dependency on Russian hydrocarbons

Source: European Commission

Strengthening Europe's energy sovereignty therefore means achieving the other two objectives of "Repower EU", through a combination of reducing the European population's energy consumption and developing clean energy production.

With regard to the first objective, we have recently seen a reduction in energy consumption of around 20%, thanks to measures combining energy sobriety and efficiency. There is a need to continue along this path in the medium and long term, including through national and European support for R&D and innovation, whilst the maintenance of prices higher than those observed before the war should continue to moderate consumption levels.

Given that our continent's sub-soil is poor in hydrocarbons in contrast to our needs, the future of Europe's energy sovereignty will also and mainly depend on our ability to promote a European economic model that drastically reduces our dependence on hydrocarbons. From this point of view, the pursuit of the sovereignty objectives set out at Versailles is perfectly compatible with achieving the climate neutrality targets set for 2050 as part of the European "Green Deal" - even if debate still rages over which energy sources should be favoured.

2.2. Nuclear vs renewables: the sorry quarrel over energy mixes

The Commission was delighted that renewable energies accounted for 39% of the electricity produced in the European Union in 2022, the first year in which more electricity was generated from wind and solar sources than from gas. In March 2023, Europe also adopted a binding target of 42.5% renewable energy in the overall energy mix by 2030, with the ambition of reaching 45%, which would almost double the current share of renewables.

Europe is in the process of mobilising nearly €300 billion under the “Repower EU plan”[11] for the development of renewable energies and biomethane production, connection and storage infrastructures, energy efficiency and the adaptation of industry. To this end, it is calling on the “Recovery and Resilience Facility” earmarked for post-pandemic recovery, in the absence of a new common loan. Europe has also confirmed the relaxation of its competition rules on concerted practices, which has fostered the launch of “industrial alliances” in the fields of electric batteries, clean hydrogen and the photovoltaic industry. Following the parallel relaxation of European rules on state aid, these three alliances have already facilitated the launch of four new "Important projects of common European interest"/"IPCEI”, which allows voluntary Member States to grant massive public funding to support technological and industrial projects that contribute to Europe's energy autonomy.

This European consensus on the development of renewable energies coexists alongside deep divergence in terms of defining the "energy mix": while de jure this is an area of national sovereignty, de facto it gives rise to ideological and political leanings that are, to say the least, heterogeneous. These differences have been expressed in particular during discussions on financial taxonomy, the revision of the directive on renewable energies, and the reform of the European electricity market. These debates are all the more heated because, in addition to arguments about the relative contribution of different energy sources to European objectives in terms of ecological transition, they mask a head-on technological and industrial confrontation between States and companies fighting to preserve or improve their competitiveness.

In terms of sovereignty alone, it is easy to point out that renewable energies have the major advantage of being produced on our soil, but also the major disadvantage of being intermittent - while storage solutions and the development of European interconnections limit their scope. As for nuclear energy, it is worth noting that it can be produced in Europe, while being "controllable" and continuous - without obscuring the fact that its use entails a high degree of international dependence in terms of uranium imports and enrichment, as well as in terms of waste treatment.

It is to be hoped that such a debate can be brought to a constructive conclusion over the next few months, and that ideological disputes do not overshadow the fact that an energy "mix" (national or European) must, by its very nature, be a balanced combination of several complementary energy sources, without being overly dependent on any one of them. It is also to be hoped that Germany's excessive dependence on Russian gas will not be replaced by France's excessive dependence on nuclear power, at a time when the industry is struggling both to ensure stable, long-term operation of older power plants and to guarantee that new EPR reactors will be commissioned on schedule and within budget. Against this backdrop, isn't the planned launch of new SMR reactors a real leap of faith, and France's lag in renewable energies a regrettable missed opportunity?

3. What kind of "open strategic autonomy" for industry and the economy?

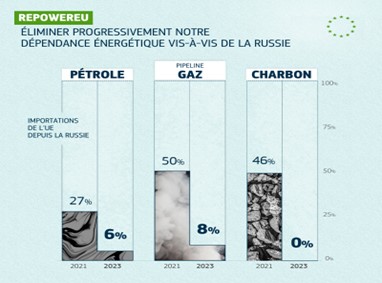

Perhaps the growing awareness of Europe's dependence on critical raw materials, which are essential for renewable energies, nuclear power and European industry as a whole, is likely to encourage greater European political convergence. In any case, "building a more solid economic base" is the third goal set by the Versailles Declaration, which again presupposes reducing Europe's "strategic dependence" in a number of areas (raw materials are mentioned, as are semi-conductors, digital technology, health and food products). The approach adopted in Versailles refers to the supply risk identification exercises recently carried out by the European Union[12] (Graph 2), which the Russian invasion of Ukraine helped to push to the top of the political agenda. It was accentuated by the intensification of economic rivalry between the United States and China, which has led the Biden administration to adopt measures to support American industries and technologies, including the Inflation Reduction Act»[13].

As "exclusive competences" of the Union since the Treaty of Rome, both trade policy and competition policy are intended to provide Europeans with a means of exercising their common sovereignty in global economic competition - provided that they agree on the content of the guidelines and decisions to be favoured. Recent convergence in terms of trade assertiveness and industrial projects reflects undeniable progress, articulated around the concept of "open strategic autonomy". However, the ambiguity of this concept means that translating it into action is fraught with obstacles, particularly due to the wide disparities in national economic performance.

Graph 2

Raw materials flows and supply risks for the European Union

Source : European Commission/Joint Research Centre 2020

3.1. More united and sovereign Europeans in trade and industry?

Tougher international economic competition led the Commission to propose a review of trade strategy in 2021[14], now more focused on ecological objectives, but also firmer on the political front. Here too, it should be remembered that the ecological and geopolitical dynamics at work combine to favour more local, and therefore European, production and consumption[15], but also to emphasise that they may prove contradictory: it would be much quicker and cheaper to use a number of Chinese products to speed up the ecological transition, even if this means increasing the strategic and economic vulnerability of our continent.

It is in this spirit that the Commission proposed an “Industrial Plan for the competitiveness of European carbon-neutral industry” giving industrial content to Europe's "Green Deal", while aiming to reduce Europeans' dependence on fossil fuels. Ursula von der Leyen emphasised this new direction during her State of the Union speech on 13 September 2023.

From a legal point of view the aim is to adopt two proposals for regulations designed to guarantee a reliable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and to strengthen the European ecosystem in terms of the manufacture of non-CO2 emitting technological products. Although these regulations include quantified objectives that are mainly incentive-based in terms of European market share, they at least reflect a new political direction aimed at better combining ecology and sovereignty.

In financial terms, the aim is to provide faster and broader support for industrial and technological projects that will give Europeans access to economic players of international stature, capable of better meeting the needs of our continent. The granting of this support has already been facilitated by the adoption of a “new temporary transitionary framework for State aid”[16] , which extends, in an exceptional and unprecedented way, the relaxation of controls on financing or tax credits granted by national authorities to their economic players in response to the pandemic and then the Russian invasion.

It is against this backdrop that industrial alliances and IPCEIs, jointly mobilising companies and Member States, are set to expand well beyond the energy sector alone: for example, the Raw Materials Alliance and the Alliance for Circular Plastics, the Alliance for Zero Emission Aviation, the Alliance for Processors and Semiconductor Technologies and the Alliance for Industrial Data, the Edge and the Cloud. - the latter two having given rise to “IPCEIs” allowing companies in many countries to receive tens of billions in state aid.

Last but not least, the Industrial Plan of the European Green Deal, like the Versailles Declaration, reiterates the benefits and virtues of trade openness for Europeans, including the availability of "resilient supply chains" through multiple agreements and partnerships with supplier countries. The Versailles Declaration does, of course, place greater emphasis on tools designed to strengthen the EU's ability to combat international distortions of competition: it has, moreover, led to the welcome adoption of a “Anti-coercion regulation” now allowing Europeans to take action against the use of trade for political ends, following Chinese retaliation against Lithuania. It also led to the adoption of a “Regulation on foreign subsidies” which would finally empower the European Union to monitor and sanction the use of such subsidies in the event of a takeover or the award of a public contract - provided that the appropriate human resources are mobilised within DG Competition for this purpose. With this in mind, on 13 September Ursula von der Leyen announced the opening of an investigation into Chinese subsidies for electric vehicles, which will mobilise the European Union's more traditional anti-dumping tools.

3.2. Very different national situations, shared sovereignty?

However, the use of the concept of "open strategic autonomy" clearly confirms the logical attachment of Europeans to the opening up of international trade, even though it is highly controversial in some countries, such as France. "Europe" is not only the oldest, but also the smallest continent, so it is its openness to the world that gives it access to many raw materials and products that it does not have in sufficient quantity. This openness to the world is all the more valued by Europeans as it also gives them access to a wide range of customers, with a generally profitable balance sheet, since the European Union has a positive trade balance, as do the vast majority of its Member States. The challenge posed at Versailles was then not so much the emergence of "European trade sovereignty", many of whose attributes already exist, but rather the difficulty of putting them to common use, given the heterogeneous economic and industrial performances of the twenty-seven Member States.

The dissonant tone of national discourse on 'reindustrialisation' or 'relocation' is symptomatic of profoundly different situations[17]: they cannot be seen as priorities in countries like Germany or Poland, where industry's share of GDP is well above the European average of 20.6%, whereas it is seen as a vital necessity in a country like France, which has fallen around 10% over the last thirty years[18] . It is in fact 'shared sovereignty' and the exercise of competences of the same name that determine national performance in terms of R&D, education and training, the labour market and social cohesion, and therefore the competitiveness and industrial dynamism of Member States: those whose performance is lagging behind find it hard to convince their more efficient partners to practise trade protectionism, which is counterproductive in their eyes, and are quicker to refer them to the structural reforms that need to be undertaken at home.

This heterogeneity is at the root of the intense debates surrounding the adoption of new trade agreements such as the EU-Mercosur, whose ratification will act as a test. Such an agreement would be welcome in terms of access to critical raw materials, which it would help to promote, and in terms of trade opportunities, particularly in services; but it would be more difficult to accept for countries that are experiencing trade difficulties and prefer to protect their agricultural sectors from stiffer competition, including by invoking “proteinic sovereignty”, like Emmanuel Macron.

The heterogeneous performance of the Member States is also a factor in the debate in terms of the funding needed to build a more solid European economic base. For while the historic relaxation of the rules governing State aid has allowed a welcome influx of public investment and tax credits in the face of the Chinese and American offensives, it has also had the effect of ending "free and undistorted competition" between companies and States. As if faced with a pandemic threat, Germany has announced its intention to pay out almost half of the €740 billion in public aid scheduled at the summer of 2023, even though it accounts for only a quarter of the Union's GDP - France follows with 22.6% and Italy with 7.7% - with the other countries accounting for 3% or less.

This development is all the more worrying given that the complementary and symbolic project of a European "Industrial Sovereignty Fund" announced by Ursula von der Leyen at the beginning of 2023[19] is still largely in limbo, despite the fact that it would have enabled the financing of joint investments that are more evenly spread across Europe. Largely based on the use of existing programmes and funding, the new “Strategic Technologies for Europe (“STEP”)” proposed in June 2023, is a very timid step forward. Here again, it is to be hoped that the Member States with the national budgetary leeway they need, unlike the more expensive countries which they consider to be less well managed, will be able to make the political and financial effort required to reconcile greater national and European sovereignty.

***

It is only one year and a half since the Versailles Declaration was adopted, both as an immediate response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and as a medium-term work programme designed to make far-reaching changes to the conditions under which sovereignty is exercised within the European Union. In this respect, the purpose of this short progress report is to highlight the substantial progress made since then in terms of military, energy and economic sovereignty, as well as the political conditions that need to be met if these are to be further enhanced over the coming years.

It goes without saying that each of the Twenty-Seven Member States will have to accept to commit fully to this perspective if it is to come to fruition, with the help of the Commission and the European Parliament, in a context marked by the shrinking of Europe at global level, which favours the pooling of forces, but also by the rise of Eurosceptic movements often opposed to the sharing of sovereignty.

As the host of the Versailles Summit and a traditional promoter of a powerful Europe, France naturally has a decisive role to play in this area. It could usefully continue to do so at a conceptual level, provided that it does not lock itself into a messianic posture that isolates it from its allies[20], but also by making the necessary adjustments in each of the three areas targeted by the declaration of March 2022. This could prove difficult at a time when the political composition of the National Assembly is strangely reminiscent of that which rejected the EDC project in the 1950s. It will remain particularly bold as long as France accumulates a triple record trade, industrial and budget deficit, which weakens it at national level while also undermining its ability to lead its partners in the Copernican revolution that Europe needs.

[1] Yves Bertoncini and Thierry Chopin, La FrancEurope 70 ans après la déclaration Schuman : projet commun ou projection nationale ? Le Grand Continent, May 2021.

[2] Luuk van Middelaar, « Le Réveil géopolitique de l’Europe », Collège de France, 2022.

[3] On the philosophical and political foundations of the concept of European sovereignty, see Pierre Buhler, Souveraineté européenne : en attendant Godot ?, Terra Nova, La Grande Conversation, July 2023.

[4] On the citizens' dimension of this debate, see also Céline Spector, "No Demos? Souveraineté et démocratie à l'épreuve de l'Europe", Seuil, Paris, 2021.

[5] On the scale of the change required, see Pascal Lamy, « Union européenne : vous avez dit souveraineté? », Commentaire 2020/1, n° 169.

[6] For a history of the theoretical controversies and practical advances of Europe as a power, Maxime Lefebvre, Europe as a power, European sovereignty and strategic autonomy: a debate that is moving towards an assertive Europe, Schuman Foundation, February 2021

[7] The EPF has absorbed and replaced the Athena mechanism and the African Peace Facility.

[8] For an overview of all the operations and missions conducted under the European Security and Defence Policy, see https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/missions-and-operations_en

[9] Pierre Vimont, The strategic interests of the European Union, Robert Schuman Foundation, September 2016.

[10] Richard Youngs, The EU’s Strategic Autonomy Trap, Carnegie Europe, March 2021.

[11] The “Repower EU” plan provides for 72 billion € in subsidies and 225 billion € in loans.

[12] See European Commission/Joint Research Center, Critical Raw Materials for Strategic Technologies and Sectors in the EU, A Foresight Study, 2020.

[13] Elvire Fabry, Comment l’Europe répond à la rivalité sino-américaine, February 2023.

[14] Une politique commerciale ouverte, durable et ferme, March 2021.

[15] See Yves Bertoncini, Relocaliser en France avec l’Europe, Fondapol, September 2020.

[16] See Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework for State Aid measures to support the economy following the aggression against Ukraine by Russia, March 2023.

[17] See Yves Bertoncini,op.cit.

[18] See Nicolas Dufourcq, La désindustrialisation de la France, Odile Jacob 2022.

[19] See Thierry Breton, A European Sovereignty Fund for an industry made in Europe, September 2022.

[20] Yves Bertoncini and Thierry Chopin, Cinq ans après, que reste-t-il du discours de la Sorbonne ? le Grand Con-tinent, September 2022.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :