Strategy, Security and Defence

Ramona Bloj,

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

By mid-April 2022, more than 7.1 million Ukrainians had been forced to move within their country. More than 4.6 million people have had to flee Ukraine since 24 February when the Russian invasion began (Figure 1). In total, more than a quarter of the population has been forced to leave their homes as a result of Russia's aggression. For Europe, this is the largest movement of a population since the Second World War, and the challenges for neighbouring countries - Moldova[1], Romania, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia - hosting the largest numbers of refugees are significant, from securing temporary accommodation and immediate access to health care, to ensuring children's education and access to labour markets.

The Host Countries

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) mid-April, the countries hosting the largest number of refugees are Poland (2,645,877), Romania (701,741), Moldova (413,374 or 15.3% of the population), Hungary (428,954) and Slovakia (320,246).

Free movement within the Schengen area, which also applies to Ukrainian refugees, makes it difficult to identify the final destination of people who have fled the war. The data put forward by UNHCR thus expresses the number of registrations. For a more complete picture of the distribution in the EU countries, we shall have to wait for residence permits or applications for asylum status or "temporary protection" to be granted.

At world level, President Joe Biden announced on 24 March that the US would take in 100,000 Ukrainian refugees, but by early April, according to the Department of Homeland Security, only 3,000 Ukrainian asylum seekers were registered in the country. More than 6,000 Ukrainians have been admitted into Canada, and 4,000 special visas have been issued by New Zealand. In a break with its traditional policy, Japan has taken in over 400 Ukrainian refugees.

According to the United Nations, nine out of ten people fleeing war are women or children. UNHCR spokesperson Céline Schmitt notes that this is a particularly vulnerable population: "These are people who need psychological support and whom we must protect from all forms of abuse and violence". She also warns of the increased support that will have to be provided to the new refugees: "The first Ukrainians to leave their country went to join relatives abroad. But the longer the war goes on, the more it will throw people on the road who are alone and without resources[2]".

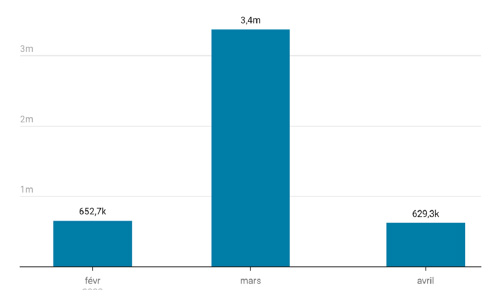

Total number of refugees from Ukraine hosted in border countries per month, since 24 February 2022

Graph 1. Robert Schuman Foundation, Source: United Nations

Graph 1. Robert Schuman Foundation, Source: United Nations

Based on data published by the national authorities, Table 1 (Appendix) provides an overview of the number of Ukrainians hosted by each Member State. However, the figures remain inaccurate and are constantly changing - for example, a person crossing the border into Poland may be counted twice: once when entering the EU and again when applying for temporary protection status in a European country other than the country of entry.

Mechanisms set up by the European Union and the Member States

The rapid European response to the Ukrainian humanitarian crisis may have come as a surprise. Indeed, since the 2015 migration crisis, Member States have remained divided on responses to migration issues. Agreement over the new Pact on Migration and Asylum, put forward by the European Commission in September 2021, has still not been met. Yet the states most reluctant to receive asylum seekers - including Hungary and Poland - are the ones receiving the largest numbers of people fleeing Russian aggression.

Overall, the European response has been structured around three lines of action: protection of people, humanitarian aid and border management and support for reception capacities.

Protection of people

While Ukrainian citizens have been able to travel to the EU without a visa for a stay of 90 days since 2017, the Commission proposed on 2 March 2022 to activate the Temporary Protection Directive, a mechanism created following the war in former Yugoslavia, but which has not been used previously. It was activated on 4 March, guaranteeing Ukrainian nationals and their family members displaced by the conflict the right of residence in the EU, access to the labour market, adequate housing, social and medical assistance and means of subsistence. It also provides for the creation of a protection status with reduced formalities. Temporary protection, valid for one year and renewable twice for six-month periods[3], is thus conceived as an alternative to traditional international protection, which presupposes an application for asylum by people who have fled their country, a process that is long for asylum seekers and complicated for Member States to manage if a large number of refugees arrive in a short time. A "Solidarity Platform", allowing Member States to exchange information on their reception capacities, has also been set up.

On 8 March, the European Commission adopted the proposal for "cohesion action for refugees in Europe" (CARE) giving Member States greater flexibility in the use of EU funds to support Ukrainians and encourage investment in housing, education, social inclusion and other social services to facilitate the long-term integration of people fleeing the conflict in Ukraine. This allows states to use the React-EU envelope (part of the NextGenerationEU recovery plan), the ERDF, the ESF and the remaining funds of the cohesion policy (2014-2020) for purposes other than those originally planned. To ease the burden on Member States' public budgets given the influx of refugees and to facilitate their reception, on 12 April the Council released 3.5 billion € of aid to States under the React-EU plan.

Moreover on 22 March the Commission opened a portal "European Research Area for Ukraine" designed to help researchers find housing and employment possibilities or to facilitate the acknowledgment of refugees' diplomas. The initiative was supported by the adoption on 6 April of a recommendation on the recognition of academic and professional qualifications. Finally, the Commission has added Ukrainian to the tool for profiling the skills of third country nationals, EU Skills Profile Tool for non-EU nationals.

Humanitarian Aid

Since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the European Union and its Member States have provided more than €2.6 billion, including €1.3 billion for humanitarian aid. Since 24 February, they have provided over €758 million in humanitarian aid. For example, the EU has made €500 million available to deal with the consequences of the war; €93 million will be allocated to humanitarian aid programmes, €85 million directly to Ukraine and €8 million to Moldova - aid for border crossings, transit points and reception centres. In addition, €330 million will be allocated to an emergency aid programme to ensure access to basic goods and services and to protect the population. Finally, €107 million of basic necessities will be provided to Ukraine.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has also announced an additional €1 billion loan to cover the needs of people displaced by the Russian invasion and to provide further humanitarian and financial assistance under the Stand Up for Ukraine project which raised €9.1 billion on 9 April. A total of €5 billion will take the shape of loans and grants from European public financial institutions, including the EBRD, and €4.1 billion are financial contributions from the private and public sectors for IDPs and refugees.

On 28 February, the European Union released an additional €90 million emergency aid package - €85 million for Ukraine and €5 million € for Moldova. In the framework of the European Civil Protection Mechanism, 20 Member States[4] have pledged material assistance to people affected by the war in Ukraine. France, the Netherlands and Austria have also provided shelter and medical assistance to Moldova, which has so far received more than €53 million from the EU, including €15 million to "support the dignified and efficient treatment of refugees as well as the safe transit and repatriation of third country nationals". On 12 April, a humanitarian operation was deployed in Chisinau, through the European Humanitarian Response Capacity (EHRC).

Under the RescEU mechanism €10 million has been made available for medical supplies - ventilators, infusion pumps, monitors, masks and gowns, ultrasound devices and oxygen concentrators - and civil protection logistics hubs have been deployed in Poland, Romania and Slovakia. €9 million has been mobilised for "mental health and trauma management support". In addition, people in need of urgent specialised hospital treatment can be transferred from one Member State to another. To date, there is also a project to create a network of mental health professionals in the Ukrainian language.

Border management and support for reception capacities

On 2 March, the European Commission presented its guidelines on the relaxation of border controls, allowing third country nationals to enter the EU on humanitarian grounds, even if they do not meet all the conditions.

Europol has also deployed operational teams in front-line countries - Lithuania, Romania, Poland Slovakia, Moldova and soon Hungary. Among other things, the agency provides support for secondary security checks at the external borders. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex is also providing its help to Moldova, in the form of technical and operational assistance.

Short- and Long-term requirements

It is difficult to estimate the impact that the arrival of almost five million Ukrainian refugees will have on the Member States. In the short term, it is important to ensure the protection and reception of people fleeing war in dignified conditions. In this context, strong involvement of governments to coordinate the participation of private networks and civil society is essential.

In the medium and long term, several unknowns, the most important of which is the duration of the war, make it difficult to estimate needs. The longer the war lasts, the more the needs of displaced persons will change in nature (for example, while in the first phase, people entering the Union's territory could count on a good material situation or had relatives in European countries, people fleeing Russian aggression in the east of the country may need different assistance, both in terms of psychological and material support).

Although daily inflows have decreased compared to the first weeks of the invasion (Figure 2), reception capacities in neighbouring countries may quickly approach their limit - Poland is hosting the largest number of refugees, and Polish authorities already warned in March that many reception centres in the country were close to reaching maximum capacity. In this context, the question of relocation of migrants arises - yet this is a double challenge: Poland was among the countries most opposed to the introduction of a relocation mechanism to manage other migratory flows in 2015, and Ukrainian refugees are often not ready to move away from the border, hoping that a return will soon be possible.

The duration of the war and the prospects for reconstruction of the country will naturally influence the return of Ukrainians. More than 537,000 people who fled the war in the first weeks of the invasion have indeed returned home. According to the Ukrainian State Border Guard Service, by 3 April more than 22,000 Ukrainians had crossed the border back into the country, perhaps encouraged by the redeployment of Russian troops to the east and Ukrainian military victories in the Kiev, Chernihiv and Sumy regions.

While the Temporary Protection Directive offers Member States a flexible framework for action and response, a reflection on the shift from immediate assistance to sustainable social and professional integration of the populations may be required in the coming months. Financial assistance to the most affected states, to alleviate fiscal pressure, will also be essential - a study published on 6 April, notes that the reception of Ukrainian refugees could cost Member States more than €40 billion[5].

Amongst other things, whilst reports have related different treatment and discrimination of third country nationals at the borders, the question of the generalisation and sustainability of reception mechanisms will arise, while an agreement on the new Pact on Migration and Asylum should, in theory, be reached soon.

Could temporary protection be applied to other migration crises? Have Polish and Hungarian positions on the issue changed? One thing is certain: the European Union, the Member States and European civil society have been able to respond to the challenge by rapidly engaging all the bodies, showing flexibility and political will.

ANNEX

| Member State | People hosted |

|---|---|

| Germany | 239 000 (4 April) |

| Austria | 51 000 (7 April) |

| Bulgaria | 79 706 (11 April) |

| Cyprus | environ 15 000 (30 March) |

| Croatia | 3 000 (30 March) |

| Denmark | 28 000 (25 March) |

| Belgium | 31 000 (7 April)[6] |

| Spain | 50 000 (10 April) |

| Estonia | 25 190 (30 March) |

| Finland | 16 000 (6 April)[7] |

| France | 43 000 (10 April)[8] |

| Greece | 16 700 (2 April)[9] |

| Hungary | 428 954 (11 April) |

| Ireland | 16 891 (31 March) |

| Italy | 88 593 (9 April) |

| Latvia | 12 000 (30 March)[10] |

| Lithuania | 43 770 (11 Aprill) |

| Luxembourg | 2 500 (15 March)[11] |

| Netherlands | 24 020 (7 April)[12] |

| Poland | 2 645 877 (11 April) |

| Portugal | 29 061 (7 April)[13] |

| Czech Republic | 300 000 (29 March)[14] |

| Romania | 701 741 (11 April) |

| Slovakia | 320 246 (11 April) |

| Slovenia | 8 000 (4 April)[15] |

| Sweden | 31 478 (12 April) |

The authors thank Monica Amaouche-Recchia, Luna Ricci, Justine Ducretet-Pajot, and Margaret Willis for their assistance.

[1] According to UN data, about one third of Ukrainian refugees remain in the country.

[2] Sophie Amsili and Jules Grandin, "Qui sont les 4 millions de réfugiés ukrainiens ?", Les Echos, 30 March 2022.

[3] If the return is still not possible, it can be renewed again for another year.

[4] Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Netherlands

[5] For an in-depth study on the cost of hospitality see Darvas, Z. (2022) 'Bold European Union action is needed to support Ukrainian refugees', Bruegel Blog, 6 April.

[6] "Un nouveau flux de milliers de réfugiés ukrainiens va arriver en Belgique", Sept sur Sept, 7 April 2022.

[7] Liisa Niemi, "Helsingiltä on kateissa yli 200 ukrainalaista lasta, jotka eivät käy koulua", Helsingin Sanomat, 6 April 2022.

[8] Jean-Marc Leclerc, "Le flux des migrants ukrainiens en France se réduit", Le Figaro, 11 April 2022.

[9] "Πόλεμος στην Ουκρανία: Πάνω από 16.700 Ουκρανοί πρόσφυγες στην Ελλάδα, 5.117 ανήλικοι", Oema, 3 April 2022.

[10] Op. cit..

[11] Tracy Heindrichs, "Around 2,500 Ukrainian refugees in Luxembourg", Delano, 15 March 2022

[12] "Safety regions, municipalities and private individuals offer refugees a safe place to stay", Gouvernement des Pays-Bas, 7 April 2022.

[13] "Portugal aceitou mais de 29 mil pedidos de proteção temporária", Observador, 8 avril 2022.

[14] Aneta Zachová, "Two-thirds of Ukrainian refugees welcome to stay indefinitely", Euractiv, 29 mars 2022.

[15] Sebastijan R. Maček, "Slovenia slow to process Ukrainian refugees", Euractiv, 4 avril 2022.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :