Ukraine Russia

Ramona Bloj

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

The value of sanctions does not only lie in their effectiveness. Sanctions are often a means of sending a clear signal of disapproval, a foreign policy stance, more moderate than an embargo, less dangerous than military retaliation. It is thus halfway between inaction and violent overreaction. In this respect, it is not surprising that the European Union has made it a privileged instrument of its foreign policy.

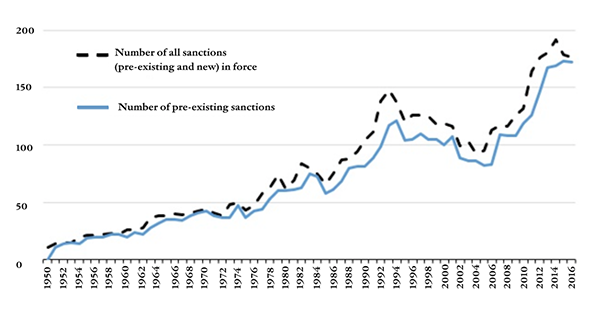

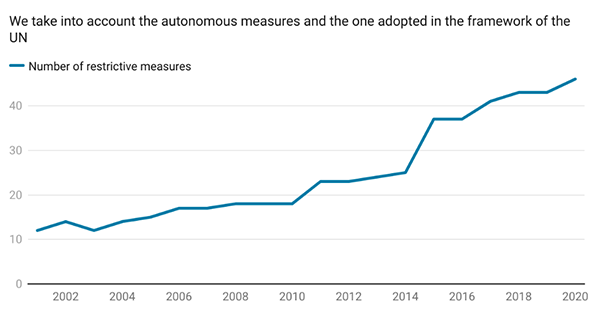

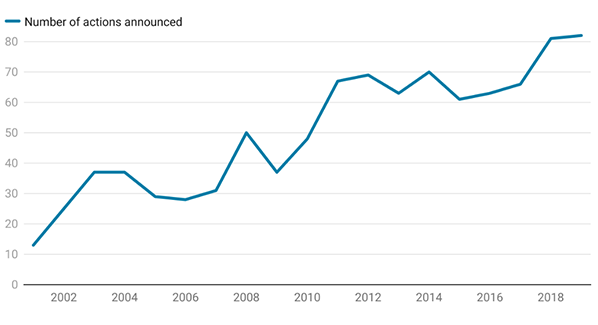

Indeed, international restrictive measures are the most visible and frequently used tool of European foreign policy. Their use has gradually increased since the Maastricht Treaty and, from the 2010s onwards, in a context of a deteriorating security environment in Europe; but we note that they are being used more and more regularly, especially in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea and the war in Donbass began. This increase is part of an international trend that was also noticeable in the United States during Obama's two terms in office (2008-2016) and especially during Donald Trump's presidency (2017-2021)[1]. It also reflects an extension of the areas of common interest and action for the Member States[2].

Source : Global Sanctions Data Base, Gabriel Felbermayr, Aleksandra Kirilakha, Constantinos Syropoulos, Erdal Yalcin, Yoto Yotov 04 August 2020, voxeu.org

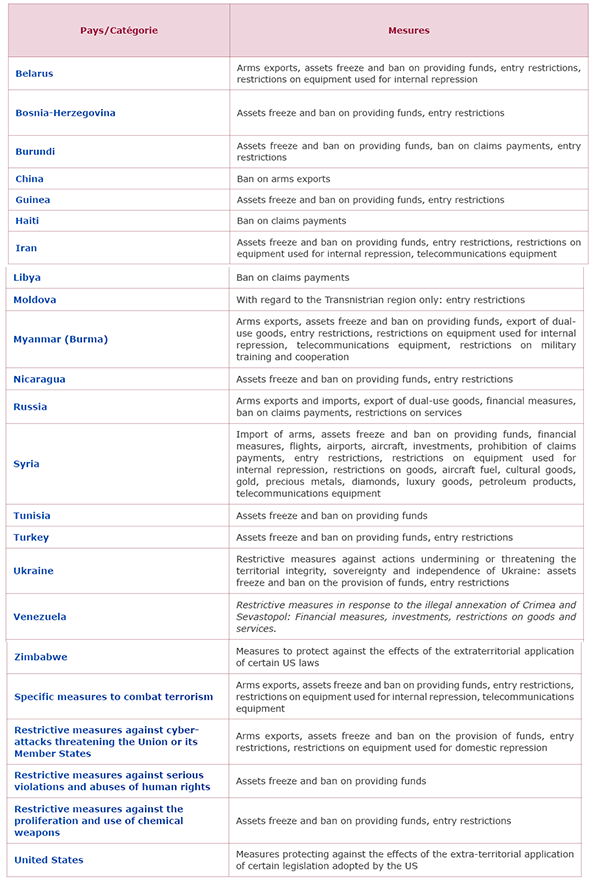

Sanctions are high on the agenda. Following the hijacking of the Ryanair flight by Minsk and the arrest of journalist Roman Protasevich and his girlfriend Sofia Sapega, the European Council of 24-25 May decided to adopt additional targeted sanctions against officials of the Lukashenko regime, already numbering 88. More than thirty States or non-State entities are targeted by one or more European sanctions, including China (for "serious human rights violations" against the Uighurs), Russia (in view of its actions in Ukraine).

By virtue of its size (448 million consumers, 27 Member States), and its economic and commercial weight (second largest economy in the world, accounting for 18.5% of world GDP, and the largest trading power, accounting for 15% of international trade in goods), the European Union has several levers at its disposal for exerting pressure to promote its values and interests. The increasingly frequent use of restrictive measures raises questions both about their effectiveness and, more broadly, about the conception of European foreign policy and its diplomatic toolbox, while Ursula von der Leyen, President of the Commission for the past year and a half, has claimed to be at the head of a "geopolitical Commission".

Historic European Sanctions

The European Union effectively acquired the capacity to adopt international restrictive measures with the establishment of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), set out in the second pillar of the Maastricht Treaty (1992). Previously, sanctions were taken under the European Political Cooperation (EPC), which aimed to develop intergovernmental cooperation in the field of foreign policy, with a view to defining and adopting common positions. In the 1980s, the EPC was mainly limited to the advocacy of broad general principles, but it sometimes adopted concrete actions. One example was the arms embargo against China in 1989 following the repression of the Tiananmen democracy movement. Common positions were also taken, for example, on the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan (1979-1989), the state of siege in Poland (1981), the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the 1980s, the expulsion of Burmese representatives in 1990 and nuclear disarmament. From the early 1990s, the European Union adopted restrictive measures against leaders who violate the principles of the rule of law and human rights, such as the presidents of the Republic of Zaire and Haiti in 1993. Subsequently, in 1999, these were sanctions adopted during the war in the former Yugoslavia and in Afghanistan. While the EPC facilitated cooperation between European States in the field of foreign policy, with the Maastricht Treaty and the introduction of the CFSP, the European Union was able to assert itself more and more clearly on the international scene. In this context, sanctions have become a key tool of European foreign policy.

Source : EU Sanctions Map. Only autonomous sanctions adopted by the European Union are shown.

The use of sanctions, their implementation and their assessment were defined by the Political and Security Committee in 2003; these guidelines were updated in 2018.

The Council's communication of 7 June 2004 lays out the main principles. Hence the Member States are "committed to the effective use of sanctions as an important way to maintain and restore international peace and security in accordance with the principles of the UN Charter and of our common foreign and security policy". The sanctions are a "support of efforts to fight terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and as a restrictive measure to uphold respect for human rights, democracy, the rule of law and good governance. Regarding implementation, "sanctions should be targeted in a way that has maximum impact on those whose behaviour we want to influence. Targeting should reduce to the maximum extent possible any adverse humanitarian effects or unintended consequences for persons not targeted or neighbouring countries. Measures, such as arms embargoes, visa bans and the freezing of funds are a way of achieving this"

On 7 December 2020, European Union adopted a new instrument, a new sanctions regime against human rights violations in the world, which makes it possible to sanction natural, legal or State entities that have allegedly violated human rights. This European "Magnitsky law" was adopted unanimously and was used for the first time in March 2021 against China, North Korea, Libya, South Sudan and Eritrea.

Adoption

Restrictive measures are adopted unanimously by the Council, on the basis of a proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. If they are diplomatic sanctions, they are implemented by the Member States; if the Council decision provides for economic or financial sanctions (thus involving a Union competence), the measures must be implemented by a Council regulation. In this case, the EU can use the political conditionality of official development assistance as a lever (e.g. the sanctions against Zimbabwe), or the abolition of the Generalised System of Preferences.

The procedure is governed by Article 215 of the Lisbon Treaty, §1 and §2, "when a decision provides for the interruption or reduction, in part or completely, of economic and financial relations with one or more third countries, the Council, acting by a qualified majority on a joint proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Commission, shall adopt the necessary measures. It shall inform the European Parliament thereof. When a decision is adopted [...] the Council may adopt restrictive measures under the procedure referred to in paragraph 1 against natural or legal persons and groups or non-State entities."

The Directorate General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union (DG FISMA) participates in the preparation of proposals for Regulations and represents the Commission in discussions with Member States. It is responsible for supporting Member States in the implementation of sanctions, transposing certain UN sanctions into EU law and monitoring their implementation. We should note that the DG FISMA is devoting increasing attention and effort to strengthening the Union's resilience to extraterritorial sanctions adopted by third countries[4].

The Union's sanctions apply to the entire country, to businesses established in a Member State, to the citizens of Member States and to any physical or moral entity linked to the commercial activity undertaken in the Union. Regulations are subject to the supervision of the European Court of Justice.

Types of sanction

International restrictive measures are defined as "the deliberate withdrawal by a government from commercial or financial relations to achieve foreign policy objectives" or as "a denial of any relationship by one or more States designed to influence the behaviour of another State on non-economic matters or to limit its military capabilities"[5]. Among the tools available to resolve foreign policy disputes (from diplomacy to military intervention), European sanctions seek to target, in order to minimise the consequences for the civilian population, and to strike a balance between actions that may appear too soft and others that are too strong[6]. International restrictive measures are the only coercive foreign policy instrument available to the EU.

The European Union mainly uses diplomatic and economic sanctions. Diplomatic sanctions are measures such as the interruption of diplomatic relations, or restrictions on the entry of persons. Economic and financial sanctions such as assets freezing, bans on financial transactions are imposed on groups or organisations, governments, companies, individuals or entities.

Depending on the scale of application, EU sanctions can be grouped into three categories: UN sanctions (implementation of sanctions adopted by the Security Council), mixed sanctions (in addition to measures adopted by the UN) and autonomous sanctions, imposed independently by the Union only.

The aim of sanctions is to "bring about change in policy or activity"[7], to force the target State to modify its behaviour[8]. Based on the goals sought, at the European level, we can differentiate five types of sanctions:

a) the promotion of democracy and human rights (e.g. sanctions against four Chinese officials adopted on 22 March 2021; sanctions against Burundi, Libya, Iran, North Korea, Belarus);

b) conflict management (Libya, Syria, Guinea);

c) non-proliferation (especially concerning the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction: Iran and North Korea);

d) deterrence (Russia);

e) the fight against terrorism (Da'esh and Al-Qaida)[9].

More broadly, sanctions may relate to a legal or safety standards issues.

The effectiveness of sanctions based on two case studies

The effectiveness of international sanctions remains difficult to measure and a matter of debate[10]. The adoption of restrictive measures is based on the assumption that the economic hardship caused by the sanctions should translate into political pressure that will eventually force the leaders of the targeted country to change their policies or lead to the overthrow of the regime in place[11]. Critics of this approach point out that, in many cases, sanctions have led to more political integration than disintegration, resulting in a national rallying effect around the sanctioned leaders[12]. Are the sanctions in place against North Korea and Syria not proof of this? The fact remains that Russian diplomacy, officially and through its networks of influence in Europe, is constantly calling for their abolition and that North Korea has repeatedly set the lifting of the very severe sanctions decided against it by the international community as a precondition for dialogue.

The Russian Case

Following the annexation of the Crimean peninsula by Russia in March 2014 and the war in the East of Ukraine, the EU imposed a series of measures initially targeting 177 individuals and 48 specific Russian entities. From July 2014, the restrictions were extended to limit trade in military technology and equipment for the Russian oil and gas industry, but also to reduce access to the EU's primary and secondary capital markets for certain Russian banks and companies. The financial and economic sanctions, coupled with a fall in the price of oil per barrel, have had a considerable impact on the Russian economy which, by 2016, had lost around $570 billion. Yet six years after the 2015 Minsk II agreements, the ceasefire is still not respected. On 2 March 2021, the Union adopted new sanctions The European Commission is expected to present a report in June that will set out policy options for responding to Russian provocations[13]. EU sanctions adopted in response to the annexation of Crimea and the violation of Ukraine's territorial integrity expire in June and September.

The Iranian Case

Compared to the Russian case, Iran is a perfect counter-example. The sanctions that the Europeans imposed on Iran in 2012 in response to breaches of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty are the toughest adopted at European level to date. Since 2006, the United Nations Security Council has adopted several resolutions supported by sanctions, demanding that Iran stop enriching uranium for nuclear proliferation purposes. As of 2012, the European Union adopted autonomous sanctions, notably an embargo on oil and petrochemical and oil products, assets freezes of the Iranian Central Bank and the country's main commercial banks, the establishment of notification and authorisation mechanisms for transfers of funds above a certain amount to Iranian financial institutions, a ban on access to EU airports for cargo flights, travel restrictions and an assets freeze on persons and entities on the list adopted by the Council. These measures come in addition to restrictive measures linked to Human Rightsviolations imposed in 2011, which have been extended every year since and are still in force. These multi-actor sanctions, imposed by the United Nations, the European Union and the United States, which spared no sector of the economy, contributed to Iran's return to the negotiating table and to the adoption of the Joint Action Plan, adopted in 2015.

But the success of sanctions can be measured by the creation of conditions for change. In other words, sanctions can pave the way for internal developments[14]. The most frequent examples are the sanctions against South Africa adopted by the United States, the European Community and Japan in 1986. Following this approach, European sanctions have the potential to be successful over time, but their evaluation is always subject to interpretation because, while they have an effect in each of the cases mentioned, their effectiveness as a foreign policy tool is difficult to quantify.

Moreover, the increase in sanctions adopted in Europe, and in the United States, evident not only in the number of entities sanctioned, but also in the scope and complexity of the measures taken[15], responds to a demand on the part of citizens: for example, according to a survey conducted in 2019, in the majority of Member States, with a few exceptions, more than 50% of respondents felt that EU policy towards Russia is either balanced or not tough enough[16]. The same trends can be seen in the United States, where the public is overwhelmingly in favour of stronger sanctions against North Korea, and a firm attitude towards China on human rights and economic practices[17]. So aren't sanctions also a new way of doing "opinion diplomacy"?

Source : calculation based on European Commission data

OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control)

Source : Gibson Dunn, 2019 Year-End Sanctions Update

***

In the European case, the adoption of international sanctions has an additional role: to contribute to the definition and implementation of a genuine common foreign policy: developments since the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty and the frequent use of sanctions demonstrate both the capacity of Member States to formulate common positions, to find a common strategic interest and the capacity of the Union to use its economic and commercial weight and its institutional capacity to respond to political (respect for human rights, democracy) and security (non-proliferation, territorial aggression, terrorism) issues and to exert real political influence.

Restrictive measures are used "by the Union as part of an integrated and comprehensive action, which includes political dialogue, complementary measures and the use of other instruments". The increase in sanctions, however, calls for the development of instruments to evaluate the measures taken and the regular publication of impact assessments. Although the European Union is developing its strategic autonomy, to be effective, sanctions should be adopted more within a multilateral framework. Moreover, a reflection on how to lift restrictive measures - a step that might prove extremely difficult, as the Russian case shows - and re-establish new bases for cooperation, for example, might support the process. This would contribute to the coherence of European foreign policy - Belarus was invited in 2008 to join the Eastern Partnership even though the country was under a sanctions regime[18] and many voices criticise the lack of clarity and consistency in the choice of those sanctioned[19].

The adoption of new foreign policy tools, such as the European Peace Facility or the European Defence Fund, could facilitate better coordination with other foreign policy instruments in order to maximise their effectiveness. Sanctions are now an integral part of the European Union's common foreign policy, which is increasingly trying to assert itself.

[1] In 2019, 1 000 names on average were added to the OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) list of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons than under any previous administration.

[2] Bastien Nivet, Les sanctions internationales de l'Union européenne : soft power, hard power ou puissance symbolique ?, Revue internationale et stratégique 2015/1 (n° 97), p. 129 à 138.

[3] Source : EU Sanctions Map. Only autonomous sanctions adopted by the European Union are shown.

[4] Cf. Mission statement, Mairead McGuinness 13 September 2020.

[5] Jentleson, B.W. (2000). Economic sanctions and post-Cold War conflicts: Challenges for theory and policy. In D. Druckman & P.C. Stern (eds), International conflict resolution after the Cold War. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

[6] Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Economic Sanctions and U.S. Foreign Policy.

[7] Bastien Nivet, op.cit.

[8] Robert A. Pape, Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work, International Security, Volume 22, Issue 2 (Autumn, 1997), 90-136.

[9] Francesco Giumelli, in How EU sanctions work: a new narrative, identifies five types of sanctions.

[10] Cf. Nicholas Mulder.

[11] Portela, Clara. European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy: When and Why Do They Work?, Taylor & Francis Group, 2010.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Andrew Rettman, Macron: EU sanctions on Russia do not work, EUObserver, 26 May 2021.

[14] Portela, Clara. op. cit.

[15] Peter Harrell, Is the U.S. Using Sanctions Too Aggressively?, Foreign Affairs, 11, September 2018.

[16] Susi Dennison, Give the people what they want: Popular demand for a strong European foreign policy, ECFR, 10 September 2019.

[17] Portela, Clara. European Unio Laura Silver, Kat Devlin And Christine Huang, Most Americans Support Tough Stance Toward China on Human Rights, Economic Issues, Pew Research Center, March 2021.

[18] Konstanty Gebert, Shooting In The Dark? Eu Sanctions Policies, ECFR, janvier 2013

[19] Martin Russell, EU sanctions: A key foreign and security policy instrument, EPRS, mai 2018.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :