Budget and Taxation

Ramona Bloj,

Marion L'Hote

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

Marion L'Hote

Foreword

2020 is not 2008. To revive our economies hit by the global recession, a new stakeholder is now taking a leading role: Europe.

In 2008, the European Commission calculated the sum of the national plans, then added a ladle of EIB loans and a tiny spoonful of EU cohesion funds to present a pseudo "European plan" of €200 billion to the press. When, two years later, the "euro crisis" brought the "Club Med" to the brink of bankruptcy, salvation was found, admittedly, in Brussels, but in the creation of a pool of loans from national budgets: the European Stability Mechanism. In short, the solutions to a crisis of European dimension, which affected the very foundations of the European monetary area, were initially national and fortunately supplemented by the monetary policy of Mario Draghi. The European Union was then prompted to invite its Member States as a matter of urgency to restore budgetary balances that had been severely shaken by the recovery plans, and even to tighten the criteria for good management set out in Maastricht. The overdue wisdom of a decade's hindsight helps us to appreciate the self-punishment that Europeans inflicted on themselves through these contradictory, ill-conceived and poorly coordinated policies.

2020. This time, the mega-crisis triggered by the pandemic is such that the temperature and pressure conditions are so high that the Heads of State and Government understand that there is no salvation without genuinely joint action. They have discovered that after thirty years of one-upmanship by Finance Ministers to block the Community budget at 1% of GDP, that the latter cannot play a useful role right now. So, a thermonuclear explosion has broken the three locks of this straitjacket: an exceptional budget five times larger was decided upon as a matter of urgency; it is to be financed entirely by borrowing, but this time it will be a Community loan, in a situation in which even a cash overdraft of 1 euro was previously forbidden; finally, to reassure future lenders, European taxes are to be introduced, to guarantee that Union's loan will be serviced.

Does the recovery of our highly integrated economies therefore depend on that of Europe? The iFRAP and the Robert Schuman Foundation have combined their respective expertise to offer an answer, which is inevitably very provisional at the beginning of spring 2021. We can see how difficult it is to compare the American and European recovery plans, even if on both sides of the Atlantic we face a common dilemma: how can we reconcile or weigh up the effect of stimuli in the very short term and the commitment to investments oriented towards the crucial, more distant objectives of the green and digital transition and competitiveness? It is easy to understand why, in its current state, the EU' s micro-budget can only produce an "out-of-focus" blueprint. It shows how urgent it is to make this 2020 'financial euro-revolution' permanent and to amplify it in support of the implementation of a real European budget adapted to the very new expectations that the mega-crisis has generated among citizens with regard to Europe.

Finally, the French reader will understand how inappropriate the "cowardly relief" expressed by too many French politicians and economists has been with regard to the inevitable suspension of the safeguards of the Stability and Growth Pact. That they must be adapted is inevitable. To abandon them would be madness. For the past twenty years, all of our governments have become adept at begging the Commission and our partners, not without arrogance, for a sort of "French right to a permanent deficit". France has lost a good part of its political credibility, only to find that it has also lost a third of its industry, abandoned control of its public finances, and dropped down several places in terms of the quality of its basic public services - without recovering the secret of its social cohesion. The only thing that has gained ground is bureaucracy, an invasive species that is even supported by ecologists, provided that there is a proliferation of what can be described as things 'green'. If we want a "Europe that protects", we must first ask it to protect us from ourselves.

*

In 2020, the Covid-19 health crisis disrupted the economy the world over.

In Europe, after some procrastination, the European Union took exceptional measures that led to the adoption of an unprecedented €750 billion recovery plan. For the first time, this will allow the European Commission to borrow. On 14 April 2021, the Commission announced its intention to raise €800 billion on the financial markets by 2026. Rated triple A, it plans to do so through a mix of issuing medium and long-term bonds (including 30% green bonds) and short-term debt securities to ensure disbursement flexibility. Payments to Member States will be staggered after six-monthly checks on compliance with performance targets. The European recovery plan will be launched as soon as the 27 Member States have adopted the new own resources mechanism. Twenty Member States have already done so. At the same time, they must submit their national recovery plans to the Commission. The Commission has recommended a six-pillar framework: "green transition" (energy renovation, etc.) for 37% of the financial envelope, "digital" investments (infrastructure improvement, cyber security, etc.) for 20%, "social and territorial cohesion" (training), "economic cohesion, productivity and competitiveness" (research and development), "health and economic, social and institutional resilience" (hospital system) and "next generation policy" (education). A "Recover" task force, headed by Céline Gauer, will examine each of the national projects, which must comprise four chapters: a general presentation, a description of the planned reforms, an explanation of their complementarity with other sources of funding (existing European funds, etc.) and a measure of the expected macroeconomic impact. It will rank each application according to eleven criteria, aimed at ensuring "relevance", "effectiveness", "efficiency" and "coherence". The dossiers must meet at least seven of these criteria to receive the Commission's approval and be submitted to the European Council for a final opinion. The Council will then have one month to study them and approve them by qualified majority. The final green light could therefore come by this summer.

As we reach a crucial moment in the implementation of this unprecedented and now much awaited European recovery plan, the Robert Schuman and iFRAP Foundations are offering you a special report to help you have a better understanding of the issues and challenges at work in terms of European finance, the exit from the crisis and Europe's recovery.

I. The Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF) 2021-2027

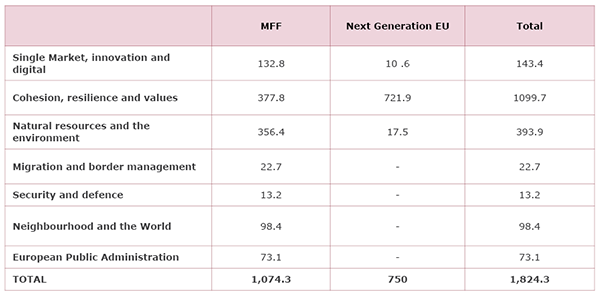

The 2021-2027 MFF was the subject of negotiations throughout 2020. The 27 heads of State and government failed to agree on the amount at the European Council of 20-21 February 2020, when the amount was cut by €40 billion. The coronavirus epidemic and the subsequent crisis only served to delay discussions and its adoption. Indeed, on 27 May 2020, following̀ the announcement of the 'Next Generation EU' recovery plan, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen proposed́ to set the MFF at €1,100 billion. After the rejection of this by the four so-called "frugal" Member States (the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Austria), who considered this amount still too high, the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, lowered it to €1,074 billion at the European Council of 17-21 July. In the end, the amount of the 2021-2027 MFF will total €1,074.3 billion, to which we have to add €750 billion from the recovery plan, making a total of €1,824.3 billion.

(in billions €)

For the period 2021-2027, the main headings, i.e. those with the highest amounts, are "Cohesion, Resilience and Values" (€377.8 billion) and "Natural Resources and Environment" (€356.4 billion). This is because 'Cohesion, Resilience and Values' includes all the funds under the cohesion policy[1]. The Common Agricultural Policy, one of the Union's flagship programmes, is part of 'Natural Resources and Environment'. Note however that the CAP allocation has beeń slightly reduced compared to 2014-2020 (in real terms weighted by inflation[2]).

The adoption of the MFF 2021-2027 by the European Parliament

While the European Parliament was supportive of the recovery plan, it felt that the amount of the MFF was far too low and intended to negotiate it. Among its demands were the establishment of democratic control of the recovery plan and a binding commitment on the Union's new own resources so that these could at least cover the costs of the recovery plan. In this respect, it adopted a resolution setting out a timetable for the introduction of own resources:

the introduction of the plastic contribution in 2021;

the border carbon tax and the tax on digital giants in 2023;

the financial transaction tax in 2024;

the common consolidated corporate tax base in 2026.

On 10 November 2020, political agreement on the MFF and the Recovery Plan was reached between the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission. With this agreement, the European Parliament made progress on some points:

an increase in the budget for some of the Union's flagship programmes, €16 billion in total (€4 billion for Horizon Europe, €2.2 billion for Erasmus, €3.4 billion for health);

the introduction of new own resources with a roadmap for the next 7 years, integrated in the institutional agreement, a legally binding text;

the conditionality of funds to the rule of law.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Only the creation of new own resources would help to pay off the debt while saving the EU budget and reducing the tax burden on national finances and EU citizens.

The Present Revenues

1. "Traditional" own resources.. hese comprise customs duties, agricultural duties and sugar levies, which have been collected since 1970. They represent just over 10% of revenue. 2. VAT-based own resource.. It is based on the transfer of part of the VAT collected by the Member States since 1979. The VAT resource represents about 10% of the revenue. 3. GNI-based own resource.. It is based on the transfer of part of the VAT collected by the Member States since 1979. The VAT resource represents about 10% of the revenue. 4. Other revenue and balance carried over from the previous year.. Other revenue includes taxes paid by EU staff, contributions from third countries to certain EU programmes and fines paid by companies. In the event of a surplus, the balance is entered in the budget for the following year. 5. Corrective mechanisms.. The own resources system aims to correct budgetary imbalances between Member States' contributions. Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden benefit from flat-rate corrections financed by all Member States for the period 2021-2027. The decision of 14 December 2020 maintained the rebates of these Member States and the share they can levy on customs duties as collection costs has been increased from 20% to 25%.

The New Revenues

The plastic packaging waste levy is the first own resource introduced on 1 January 2021, in the form of a national contribution on the quantitý of unrecycled plastic packaging waste, with a call rate of €0.80 per kg. The contributions of Member States whose GNI per capita is below the EU average are adjusted on the basis of a lump sum corresponding to 3.8 kg of plastic waste per capita per year. These resources are due to represent about 4% of the EU budget.

On 10 November 2020, negotiators from the Parliament, the Council and the Commission reached an inter-institutional agreement on budgetary discipline, cooperation in budgetary matters and sound financial management which introduces new own resources for the period 2021-2027, to cover the reimbursement of "Next Generation EU". Revenue in excess of repayment obligations will finance the Union budget, in accordance with the principle of universality[3].

The Commission must submit, by June 2021, proposals for new own resources based on:

• a border carbon adjustment mechanism;

• a digital tax;

• a revised́ emissions trading scheme (introduced by 1 January 2023).

It must also formulate, by June 2024, its proposals for other own resources, which could include:

• a financial transaction tax ;

• a financial contribution linked to the corporate sector (possibly in the form of a new common corporate tax base).

____________________________________________________________________________________

The agreement also provides for at least 30% of the total amount of the EU budget and Next Generation EU spending to support climate objectives. A further target is to reach 7.5% of annual spending on biodiversity targets from 2024, and 10% from 2026. The Member States approved the agreement on 10 December 2020.

On 10 February 2021, the European Parliament adopted the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) which, with €672.5 billion in grants and loans, is the largest component of the recovery plan[4]. The Council endorsed it the following day.

II. EU Responses to the 2020 crisis

A unique crisis

The economic crisis of 2020 was unusual because it was primarily health related, leading to many uncertainties. To limit the number of cases and therefore deaths, States took social distancing and then lockdown measures, which resulted́ in a shock to the world's economy for several reasons: the first impacted supply: from January to April, China, then the epicentre of the pandemic, implemented lockdown in several of the country's major cities, which halted exports; the second impacted demand, which occurred at the same time as the first, something that was new and unique tò this crisis: the reduction in industrial activitý in China, and then in Europe, led to a negative demand shock on raw materials. In addition, the successive lockdowns have constrained consumption (according to French Insee, household consumption fell from €47 billion in February 2020 to €31 billion in April 2020).

In 2020, the crisis caused a 9% contraction in international trade compared to the -11% of the 2008 crisis which occurred over a period of 2 years. This was a global crisis of unprecedented proportions: the European Union's GDP contracted by 6.4% in 2020 and by 6.8% in the euro zone, compared to -4.3% in 2009 after the financial crisis.

To deal with the crisis, two types of policy have been implemented at both European and national levels: budgetary and monetary policies, which have two tools at their disposal: the key interest rate, which is used to influence access to bank credit, and non-conventional tools such as quantitative easing.

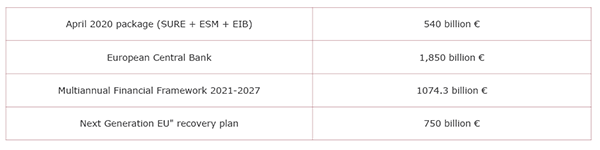

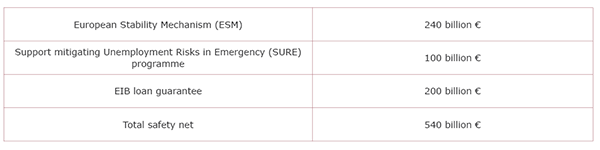

A 540 billion € support package

On 9 April 2020, EU Finance Ministers announced the introduction of a €540 billion "safety net", mobilising or creating various support mechanisms.

The European Stability Mechanism (MES) will provide up to 240 billion € to fund the health systems of the 19 euro area States which might need it (the Pandemic Crisis Support). Loans totalling up to 2% of the countries' GDP have also been provided for.

he European Commission has introduced a programme of national short-time working schemes, the SURE (Support mitigating Unemployment Risks in emergency) programme, which came into force on 24 April 2020, in the form of low-cost loans to assist Member States. This instrument has helped Member States strengthen their short-time working schemes. To date, the Commission has approved financial assistance of €90.3 billion for 18 Member States (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Czech Republic). These sums are loans that will have to be repaid between 2030 and 2040.

The creation by the European Investment Bank (EIB) of a €200 billion loan guarantee for SMEs in difficultý. The amounts are being deployed through a guarantee fund of €25 billion, to be matched by the Member States.

1. What the ECB has done

On 12 March 2020, ECB Chairwoman Christine Lagarde announced a €120 trillion private sector asset purchase plan, in addition to the €20 trillion monthly purchase programme launched in November 2019. On 18 March, the ECB announced a specific €750 billion asset purchase programme (the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program), running until March 2022. This is a large-scale economic stimulus allowing States and companies to borrow at low prices to finance their economic and social recovery. On 4 June, Christine Lagarde announced €600 billion in additional debt purchases. The ECB indicated́ that it would reinvest the securities participating in the PEPP at maturity until̀ the end of 2022, allowing it to steer this stock of assets over the long term. On 10 December, the ECB announced that it was further increasing its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program by €500 billion, bringing the total to €1,850 billion.

The ECB also announced the reinvestment of its interest rate gains in asset purchases until̀ the end of 2023. Interest rates and the asset purchase programme remain unchanged.

2. Impact of the ECB's policies to date

Firstly, with regard to State debt, to protect the health system and jobs during the crisis, the States had to take on debt. To reduce the cost of debt, i.e. interest rates, the ECB bought debt securities via Quantitative Easing. The effect can be quantified: Italian 10-year debt securities were quoted at a rate of 1.4% on 1 January 2020, compared with 0.58% on 2 February 2021 and even dropping to 0.5% since Mario Draghi became President of the Italian Council. This is not the first time that the ECB has succeeded in reducing the burden of government debt: Greek debt rates were over 10% in 2015 compared with 0.65% today. Another positive, significant indicator for recovery is the rate of credit generation to non-financial companies (businesses), which was up 13.1% in December 2020 compared to December 2019[5], it was 7.1% in June compared to June 2019. Thus, the zero-interest rate and Quantitative Easing policy is fulfilling its role in allowing cheap debt for States and easy access to loans for companies. Thus, to date, the ECB's crisis management balance sheet can be considered́ positive.

The Recovery Plan " Next Generation EU "

1. The Recovery Plan's various proposals

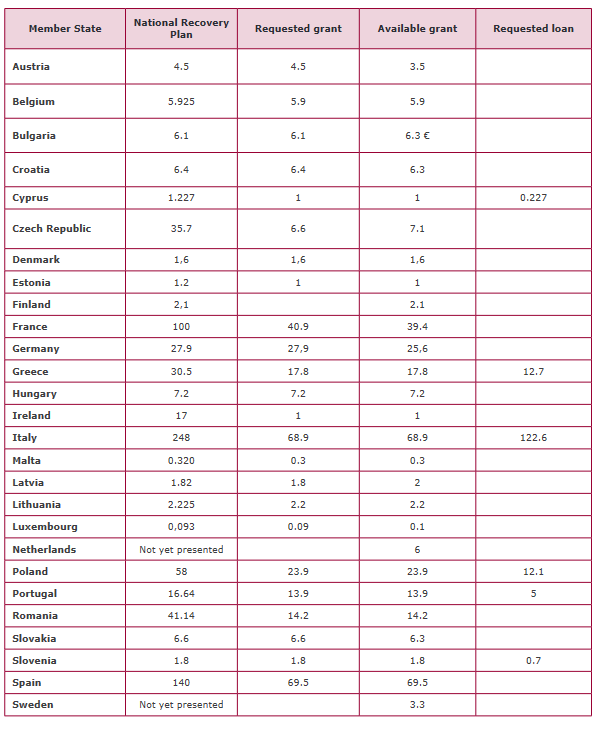

The recovery plan is above all the result of the joint efforts of the Franco-German couple, whose relationship has grown stronger over the course of the crisis. On 18 May 2020, Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron called́ for a European recovery plan of €500 billion in grants. On 27 May, the Commission announced the outlines of a recovery plan, "Next Generation EU" consisting of €500 billion in grants and €250 billion in loans, for a total amount of €750 billion. At the European Council of 17-21 July, the 27 heads of State and government reached agreement on the overall amount but with a different distribution plan: €390 billion in grants and €360 billion in loans. The Commission thus plans to borrow around €150 trillion a year until 2026, making the Union the largest issuer of euro debt. While the amount of the plan waś agreed at €750 billion (at 2018 prices), it now stands at around €807 billion in current prices[6].

2. Distribution of subsidies

Italy and Spain, being the countries most affected by the health and economic crisis, are to be allocated the most funding, i.e. €81.4 and €74.4 billion respectively. France, equally affected, will receive €40 billion.

The difference is mainly due to the criteria considered for the distribution of the grants. Thus, 70% is to be engaged in 2021 and 2022 and their distribution is based on the Commission's proposal taking on board the population, GDP per capita and the unemployment rate over the period 2015-2019. The remaining 30% is to be allocated in 2023 and calculated again on the basis of population and GDP per capita, but also on the decline in GDP that each Member State will facé in 2020 and 2021. The unemployment criterion would then be removed. Finally, the amounts received must not exceed 6.8% of the GNI (Gross National Income) of each Member State. These criteria explain why States such as Poland, Greece and Romania, relatively unaffected by the health crisis, are receiving large amounts.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Debt increased significantly in 2020 due to the health crisis. According to Eurostat, public debt increased in 2020 to 90.7% of GDP in the Union (up from 89.7% in 2019). In the euro area, it increased́ by €1.24 billion in 2020 to €11.1 billion, i.e. representing 98% of gross domestic product (GDP) compared to 83.9% in 2019. The public deficit ratio rose to 6.9% in the Union (compared with 0.5% in 2019) and to 7.2% of GDP in the euro area (compared with 0.6% in 2019). This increase can be attributed in particular to the significant increase in borrowing by governments to finance their support measures in response to the economic consequences of the pandemic. Greece saw its borrowing increase by 25% last year, bringing its debt level to €341 billion, or 205.6% of GDP. This is the highest ratió in Europe in terms of the size of the economy. In Italy, the country's debt ratio stands at 155.8% of GDP, an increase of 21.2 percentage points compared to 2019. In absolute terms, Italy is the most indebted country in Europe with a debt of €2570 billion. Germany saw its debt rise by 10% to 69.8% of GDP and France recorded́ an 18-point increase to 115.7% of GDP. Estonia is a good performer with a debt-to-GDP ratio of only 18.2%

____________________________________________________________________________________

3. Conditions to be eligible for subsidies

The countries benefiting from the subsidies presented, mainly at the end of April 2021, their plan which will have to comply with the Union's values ("financial interests should be protected in accordance with the general principles", editor's note: Article 2 of the TFEU) and be part of a commitment́ to ecological transition. The agreement indeed imposes 37% of green investments and 20% dedicated́ to the digitalisation of the economy.

The beneficiaries' plans will have to be approved by the Commission and the Council, by a qualified majoritý. States will be able to trigger an "emergency brake", if they consider that the beneficiary does not respect the conditions set. This means that, at the request of one or more Member States, checks might be undertaken. In the event of non-compliance, corrective measures or sanctions could be suggested.

4. The 2020-2058: introduction of national recovery plans and the reimbursement of the debt.

By 17 May 2021, 22 Member States had ratified the Own Resources Agreement. Five countries (Austria, Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands, Romania) have yet to ratify the €750 billion recovery plan process. The ratification of this agreement is indeed essential for the implementation of the recovery plan as it conditions the raising of funds on the financial markets by the Commission, the distribution of the recovery plan funds to the Member States as well as the repayment of the common debt.

(in billion €)

We should recall that the entry into force of these new own resources aims to finance the Union's recovery plan and, at the same time, to make up the deficit in the European budget caused by the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union in 2020. Once all Member States ratify the agreement on own resources, the EU will have new sources of finance, designed to facilitate the repayment of the common debt at its maximum maturity date of 2058. The Commission will introduce new own resources in three stages: 2021, 2023 and 2026.

- The Commission will make its proposals on the creation of potential new own resources for the period (2021-2027) in June 2021.

The plastic tax calculated on the weight of non-recycled plastic waste, set at €800 per tonne, came into force on 1 January 2021 and will be paid through national contributions. This means that the less a country recycles its plastic waste, the more it will have to contribute to the tax. This is particularly the case for France, where 70% of plastic waste is not recycled and which, along with Germany and Italy, is expected to be the three main contributors to the new tax. On the other hand, Cyprus, Lithuania and Bulgaria recycle between 60 and 75% of their plastic packaging, making them the countries with the highest recycling rate.

The Commission is also planning a revised proposal for the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), extended to the aviation, maritime and building sectors, in June 2021.

- For phase 2, the recovery plan as it has beeń negotiated́ provides for the entry into force by 1 January 2023 of two new sources of funding.

These include the carbon adjustment mechanism at borders, which aims to tax companies outside the EU that want to export their goods to Europe without respecting the same environmental rules, and the digital tax (also known as the GAFA tax), which aims to harmonise the taxation of digital giants. According to the opinion polling firm Kantar, Amazon's actual turnover in France reached €6.6 trillion in 2018 for a total of €40 million in taxes actually paid.

- Finally, for phase 3, which should run from 2023 to 1 January 2026, the Commission is studying the possibilitý of raising new own resources.

Among these projects is the common consolidated corporate tax base, which is back in the newś following President Biden's proposal in the OECD negotiations for a global minimum tax on profits of 21%. The Commission would also like to bring into force a financial transaction tax (also known as the Tobin tax or FTT) by 2026. A tax of 0.01% on financial transactions would bring in €60 billion for the EU.

When and how will the EU Next Generation Plan money be borrowed?

The borrowing will start as soon as the national, and in some cases regional, parliaments of the Member States have ratified the own resources decision. Johannes Hahn, EU Budget Commissioner, said́ at his press conference on 14 April 2021 that the Union's structures "will be ready by June and theoretically we could start borrowing then but it depends on how quicklý the Member States complete the ratification process".

The Commission plans to borrow around €150 billion a year until 2026. The plan will be distributed́ over the next five years and one third will be dedicated́ to reducing CO2 emissions. Each of the 27 member States can get 13% of their share this year in the form of pre-financing before the projects funded by the scheme reach the agreed targets. So if governments choose to focus on the grant component of pre-financing this year, the EU's borrowing in the third quarter could, according to Johannes Hahn, total around €45 billion. The Commission's strategy to avoid the displacement of EU government borrowing is to publish a financing plan every six months to investors and stakeholders for greater visibilitý and transparency.

The Commission will use variable maturity bonds and short-term debt instruments, based on a diversified funding strategy. The annual borrowing decision as defined in the Commission's Governance Decision will set a maximum ceiling for borrowing operations planned over one year. It will define a range for the maximum issue amounts of long-term and short-term funding, set the average maturity of the Union's long-term funding and determine a limit amount per issue. The six-monthly financing plan will list the loans to be contracted in the coming six months, within the limits set by the annual borrowing decision. The Commission will regularly publish the amounts planned to be financed by bonds, the target dates of auctions for bond and short-term debt issues, indications of the planned number of syndicated operations and their overall volumes.

Repayments are expected to start in 2028 and continue until 2058. The loans will be repaid by the borrowing countries and the grants will be repaid from the funds raised through own resources. However, the strategy is yet to be defined.

The necessary review of the European budgetary rules

The health crisis has only aggravated the mismatch between the budgetary rules and the economic context in the Member States, currently marked by soaring public debt, low interest rates, but also by the need for investment in the ecological and digital transition, in human capital and, more generally, in measures to improve economic competitivenesś. The creation of a common European debt capacity is also a game changer. While it is difficult to imagine going back to the pre-crisis rules, the question is what to plan, which rules will have to be relaxed, modified or even changed, how to manage (without cancelling) the debt linked to the Covid-19 crisis, to improve support to the recovery and increase the resilience of European economies. In this context, many economists and political leaders have called́ for an overhaul of the European budgetary framework, both of the rules and of the institutional architecture of budgetary surveillance (see, for example, the Conseil d'Analyse Economique note by Philippe Martin, Jean Pisani-Ferry and Xavier Ragot[7]).

The current budgetary rules are both fairly simple to summarise and complex in their interpretation[8]. They essentially comprise elements established by the European treaties: the Stabilitý and Growth Pact (SGP, 1997), the Six-Pack (2011), the Two-Pack (2013) as well as the Inter-State Treaty on Stabilitý, Coordination and Governance (TSCG, 2012). This involves a framework for the trajectory of the public balance (-3% of GDP) and the structural balance (i.e. excluding the effects of the economic cycle) with a medium-term objective set at -0.5%, and to achieve this, a minimum structural effort that cannot itself be less than 0.5 points/year.

An expenditure rule imposing a growth in net "controllable" expenditure excluding interest on the debt, pensions and transfers to local authorities and the Union, excluding temporary measures, which cannot exceed a rate corresponding to potential growth in the medium term (in volume). Finally, a debt rule with a ceiling fixed at 60% and, if this is exceeded, an obligation to reduce the amount of surplus debt by 1/20th per year. All of these rules have two components: a corrective component when the 3% deficit threshold is breached́, and a preventive component when it is respected́.

On 26 March 2020, the general derogation clause of the Stabilitý and Growth Pact waś activated suspending its application during the crisis. France took the opportunity to raise question regarding the need to carry out revisions, rightly pointing out that the increase in public debts would not enable application at the end of the crisis (i.e. probably after 2022) of 1/20th reductions in the inserts for the Member States. Such a rule would lead to debt reductions of nearly 5 points of GDP/year, which are hardly feasible. The question of the rigiditý of the European treaties means that revisions will have to made "in the margins", but which will nevertheless have to reconcile the imperatives of the 'spending' and 'frugal' countries.

iFRAP and the Robert Schuman Foundation have given thought[9] to a more global development leading to the implementation of a renewed expenditure rule, henceforth registered in levels and values (and no longer in volume and expressed as a percentage of GDP). If this option were chosen, it would have to be calculated in such a way as to ensure that the level of public expenditure in each Member State converged with that of its public revenue. In other words, to ensure that the medium-term objective is zero or positive in the long term, which would be a reformulation of Article 3 of the TSCG sought by Germany in 2012. This rule could be combined with a golden rule allowing the spending ceiling to be exceeded by investment measures in the event of a crisis, with the agreement of the Commission, while at the same time allowing automatic stabilisers to operate.

The idea of replacing the current rules by standards based simply on sustainability indicatorś does not seem sufficient to us: sustainability indicatorś such as the average interest rate on the debt stocks or the ratio of the interest burden to GDP evolve only very slowly and when interest rates on new loans rise again, the interest burden could well continue to fall, even in the event of a gradual normalisation of the ECB's monetary policy after 2022. The focus should therefore be on limiting the debt stocks[10], and to do this, with the introduction of a debt brake to reduce this stock, pending the next crisis.

***

Europe is facing an unprecedented crisis and it is a test in which we must not be mistaken in our solutions. The risks are so great that the various proposals mean that all the basic rules of public management are being forgotten. The Commission's major €750 trillion borrowing plan, which is a decisive step towards the recovery and resilience of the European Union as a whole, is not a free gift. It will be borne by the Member States and thus by European citizens. Hence, own resources for the period 2021-2027 to finance the EU budget, excluding the recovery plan, will increase by 0.2 percentage points of Member States' GNI compared to the previous period (i.e. from 1.2% to 1, % for payment appropriations[11]). This collective increase offsets the decrease in European GNI caused by the exit of the United Kingdom from the Union (+0.09 points) and the emergency measures linked to the health crisis (+0.11 points).

The States are guaranteeing the recovery plan: To this first element must be added the Next Generation EU recovery plan which will lead to an additional temporary increase in the own resources ceilings. Thus, until 2058, the ceiling will be raised by 0.6 points of the GNI of the Member States of the Union. These ceiling increases do not imply a symmetrical or automatic increase in Member States' contributions. But they are "ceilings" against which appeals can be made by each State as necessary. This availabilitý thus provides a guarantee to investors[12]. On the understanding that this would be a temporary and final appeal[13].

Proposal n°1: Clarify in trillions of euros until 2058 the maximum scope of the guarantee commitments made by the Member States in the event of the European Union encountering difficultý in meeting its borrowing obligations or in the event of an appeal made by a Member State in a state of insolvencý.

There is a second risk concerning the creation of additional own resources to finance repayment from 2028. On this point, the Commission must formulate proposals by 2023 (carbon tax at the borders, digital tax, etc.), so as to offset the debt stimulus maturing from 2028. However, there is a significant risk of failure on this point, which would lead to an increase in Member States' contributions (traditional own resources and revenue deductions), which once again calls for additional forward planning of national public finances so that sufficient room for manoeuvre can be created.

Proposal n°2 : Return to a ceiling of 1.2% of GNI for the participation of Member States in the context of the negotiation of the 2028-2034 Multiannual Financial Framework and putting an end to the current policy of historical "rebates" granted to certain Member States (Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden). And anticipating the reduction of debts from 2028 onwards (€25 billion per year) without increasing the EU budget.

The recovery plan was the subject of tough negotiations resulting in a keý for the distribution of the FRR (Recovery and Resilience Facility) subsidies according to two phases of 70%/30% to be activated from 2021 and then from 2025 onwards. The architecture of the distribution keý of the first phase raises questions: by taking the population of the Member State, in inverse proportion to the GDP per capita and on the basis of the unemployment rate observed between 2015 and 2019, it is close to that of the cohesion funds. But limits have beeń otherwise placed on the allocation of funds per country. This results in losses for countries hard hit by the crisis such as France (-3.7 billion), Spain (-3.5 billion), Greece (-7.7 billion), to the benefit of some 'frugal' countries or countries benefiting from historic rebates (Germany +4.2 billion, Netherlands, +978 million) and Italy (+12.8 billion). France requested and obtained a better consideration of the stimulus effects by considering in the 30% section growth in 2020 and cumulative growth in 2020 and 2021. This factor increased the French "rebate" by 4.32 billion, but also that of Spain by 2.36 billion, Germany by 2.31 billion and the Czech Republic by 2.02 billion

Proposal n°3: be fully transparent about the criteria used to allocate the stimulus packages per country for the benefit of European citizens (how much is gained or lost per country under the capping rules). A simple rule of equal distribution per capita corrected by paritý of purchasing power might enable the achievement of this objective.

While the recovery plan enables the safeguard of the Union's cohesion, its allocation cannot be without counterpart. The funds must be earmarked and used in accordance with their purpose in support of national recovery plans. The 30% to be released from 2025 onwards will be conditional on the fulfilment of precise criteria defined in the framework of their recovery and resilience programmes published annually in conjunction with the national stability programmes. But for the common monetary policy to play its role, national budgetary policies must not be too divergent. Yet the crisis has taken its toll, which implies that some common fiscal rules (SGP, Six Pack, Two Pack, TSCG) may change. Like the Governor of the Banque de France, we believe that it is imperative to maintain the pegs constituted by the 60% public debt and 3% deficit targets, as well as the spending rule. On the other hand, we feel that it is impossible to keep to the debt reduction rule of 1/20th per year. In this sense, the following proposals can be made:

Proposal n°4: Keep the 60% debt to GDP and 3% deficit to GDP to maintain common targets and avoid the break-up of the area. Add a medium-term objective of balanced public accounts (see MTO): add a target for public spending in relation to GDP of 50 or 52%; set up a constitutional debt brake mechanism in all Member States with safeguard clauses in the event of an economic downturn.

Proposal n° 5: anticipate the hypothesis, as daunting as it is likely to be, of a return of interest rates to a "normal" level. This whole balance is obviously dependent on the maintenance of extremely favourable interest rates for a few more years. In the event of a return to more usual interest rates, which would make the management of the crisis even more difficult, we must alreadỳ envisage a full policy review.

The sustainability indicator of the debt burden alone does not allow for the creation of the budgetary margins of manoeuvre necessary to face the next crisis because the uncertainties surrounding the burden of the debt are too high. It is therefore necessary more than ever before for European countries to equip themselves with the appropriate budgetary tools. Maastricht is not out-dated; on the contrary, it must be strengthened.

[1] A recovery plan for Europe - key features - Consilium (europa.eu)

[2] www.la-croix.com/Economie/PAC-lenveloppe-lagriculture-francaise-reste-stable-2020-07-21-1201105821

[3] The Union's revenue | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament (europa.eu)

[4] www.europarl.europa.eu/news/fr/press-room/20210204IPR97105

[5] www.banque-france.fr/statistiques/credit/credit/credits-aux-societes-non-financieres

[6] Commission ready to raise up to €800 billion for recovery (europa.eu)

[7] https://www.cae-eco.fr/pour-une-refonte-du-cadre-budgetaire-europeen

[8] Vade-mecum sur le Pacte de stabilité́ et de croissance, Commission européenne, édition 2019.

[9] See Olivier Blanchard "Que faire des règles budgétaires européennes ?", Le Grand Continent, 22 February 2021 or Jean Pisani- Ferry, Le Monde, 27 March 2021.

[10] https://www.fipeco.fr/pdf/Le%20nouvel%20%C3%A9conomiste%2008.04.2021.pdf et www.fipeco.fr/pdf/Le%20nouvel%20%C3%A9conomiste%2031.03.2021.pdf

[11] Contrairement au budget de l'État, le budget de l'Union est équilibré́ ou en excédent sur la programmation pluriannuelle. En conséquence, la décision ressources propres (DRP) du 14 décembre 2020 considère que les dépenses sont toujours couvertes. Les augmentations autorisées sont de 1,2 % à 1,4 % pour les crédits de paiement et de 1,26 % à 1,46 % pour les crédits d'engagement.

[12] Voir A. Holroyd, Avis de la commission des finances sur le projet de loi autorisation l'approbation de la décision relative au système de ressource propre de l'Union, 20 janvier 2021, p. 32, https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/rapports/cion_afetr/l15b3781_rapport-fond

[13] La Commission doit au préalable tirer sur la marge de crédits disponibles sous le plafond des ressources propres. Voir Cour des comptes, avril 2020, p. 34, https://www.ccomptes.fr/sites/default/files/2021-04/NEB-2020-Prelevement-sur-recettes-en-faveur-Union-europeenne.pdf

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :