Africa and the Middle East

Alexandre Kateb

-

Available versions :

EN

Alexandre Kateb

I. Africa and the Pandemic

A. Epidemiological and socio-demographic factors

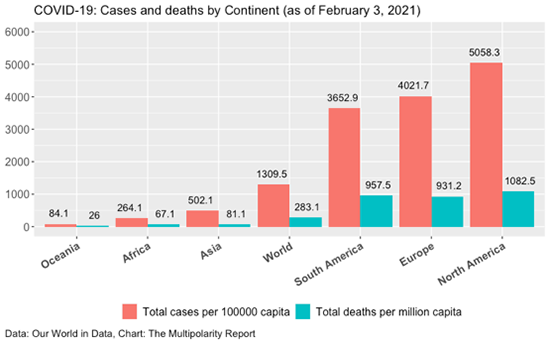

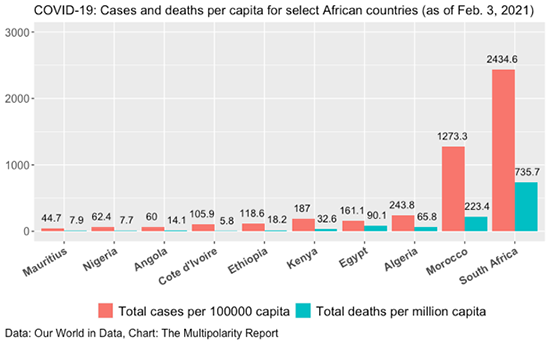

According to official statistics, the African continent has been relatively spared by the Covid-19 pandemic compared to Europe, America and Asia. The factors behind the low incidence of coronavirus in Africa are not fully understood. According to the WHO, the African continent has benefited from certain structural factors such as the limited international connectivity of most African countries, with the exception of some regional "hubs" such as Johannesburg, Casablanca, Addis Ababa and Nairobi. Incidentally, the most 'connected' African countries such as Morocco and South Africa have incurred the highest prevalence rates of Covid-19, which may lend credence to this explanation[1].

Moreover, and generally speaking, the population of the African continent is demographically much younger than that of other continents, although there are marked differences from one country to another. Average population density is also lower in Africa than in Europe, Asia or America[2]. The low incidence of Covid-19 in Africa may be attributed to socio-cultural characteristics. For example, there are very few old people's homes in Africa and in most African countries the elderly are directly cared for by their descendants according to strong customs and traditions. Some African countries are also said to have benefited from the experience gained in the fight against the Ebola epidemic[3] which spread initially in Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea and Liberia in 2013-2014, with a subsequent outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2018. At the time, these countries and their neighbours developed crisis management protocols that included a reorganisation of health infrastructures to deal with the crisis combined with the deployment of an arsenal of tests, tracing measures and the isolation of patients suffering from the virus, coupled with prophylactic measures (use of hydro-alcoholic gel and protective equipment) and restrictions on national and international mobility. Leveraging on that experience, Uganda and Rwanda closed their borders even before the first case of Covid-19 was detected on their territory.

Some researchers attribute the low rates of Covid-19 infection in many African countries to the limited number of tests performed in their populations. One study has pointed to the gap existing in some countries between the official statistics on Covid-19 prevalence and the share of the population which developed anti-bodies against the virus. In general, Africa has structural vulnerabilities with much higher poverty rates than the rest of the world, reduced access to health facilities and a significant number of people with co-morbidities or weakened immune systems, due to co-infection with tuberculosis or HIV. According to a study by Afrobarometer, two-thirds of Africans are at increased risk of exposure to Covid-19 due to precarious living conditions and lack of access to basic public services. The risk varies from 11% of the population in Mauritius to 92% of the population in Niger and Uganda. Moreover, according to the same study, 26% of Africans face a high risk of exposure and low resilience in the event of infection. Finally, less than a third of Africans (30%) would have housing and income conditions suitable for long-term confinement.

B. African States' response to the pandemic

2.1. Health restrictions and social distancing measures

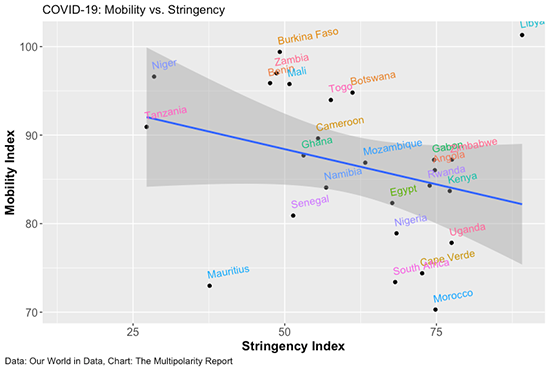

Most African countries have introduced mobility restrictions and social distancing measures to contain the pandemic. The stringency of these measures as evaluated by the Stringency Index[4], varies from one African country to another. Likewise, the actual effectiveness of these policies varies greatly. To evaluate the latter, we compiled a mobility index (Mobility Index), on the basis of GPS tracking data provided by Google. Our mobility index aggregates four dimensions: daily duration of time spent on public transport, daily duration of time spent at work, daily duration of time spent in leisure facilities and shops, and daily duration of time spent at home.

Some African countries have implemented extremely strict policies and achieved significant reductions in social mobility. When followed by the entire population, these measures have reduced the speed of circulation of the virus. More importantly, they have alleviated the overload created by the pandemic on infrastructures that would have otherwise become saturated. To combine the two dimensions - the stringency of the implemented measures and their actual impact - we designed an Efficacy Score equal to the quotient between the observed reduction in mobility (1-MobilityIndex) and the stringency of the restrictions (Stringency Index). Based on this score, calculated for 26 African countries, Mauritius comes first, followed by Morocco, South Africa, Senegal and Cape Verde. At the other end of the spectrum, in countries such as Libya and Burkina Faso, the restrictive measures had no impact on social mobility.

EfficacyScore = (1-MobilityIndex) / StringencyIndex

2.2. The economic and social impact of the pandemic and the measures taken to remedy it

While the pandemic's impact on health has not been as severe in Africa as in other regions of the world, its political, economic and social impact on African economies and populations has been considerable. The economic impact first results from the restrictive measures taken at local level to contain the spread of the virus, second, it stems from the temporary drop in global demand for raw materials (oil, minerals, agricultural products), manufactured goods and services (tourism, air transport) and, finally, from the impact of the pandemic on intra-African trade.

According to the IMF's October 2020 forecasts, African States are expected to experience negative growth rates in 2020 and are set to return to their pre-crisis GDP only in 2022 or even 2023. More specifically, according to the IMF, activity is expected to contract by 3% in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020. By 2021, African growth is expected to recover to 3.1%. The IMF notes that "Sub-Saharan Africa is facing an unprecedented health and economic crisis which, in the space of just a few months, has jeopardised years of hard-won development progress and disrupted the lives and livelihoods of millions of people". In South Africa, for example, more than 2.2 million jobs were lost in the second quarter of 2020, or 14% of all existing jobs.

Moreover, according to the World Bank, remittances dispatched by migrant workers toward Sub-Saharan Africa is set to decline by 9% and 6% respectively in 2020 and 2021, thereby worsening food insecurity and poverty in the countries that are most dependent on these transfers.

More generally the IMF stresses that "the region's prospects will depend on the availability of additional funding and transformational national reforms that will strengthen resilience (increased revenues, digitalisation, improved transparency and governance), accelerate medium-term growth, create opportunities for a wave of new entrants to the labour market and advance sustainable development objectives". The situation is hardly more enviable for the countries of North Africa whether for oil exporters such as Algeria and Libya, faced with a sharp fall in the price of black gold in the first half of 2020, or for countries exporting manufactured goods and services such as Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt which have suffered from the slump in regional demand (European Union, Turkey, Gulf countries) for these goods and services.

Moreover, the restrictions implemented to contain the pandemic, on the backdrop of an economic and social crisis, have increased people's exasperation, especially when the purpose of these restrictions was not clearly explained, and when they were not backed by adequate support measures. In Nigeria, for example, there were large-scale demonstrations in the country's major cities in October 2020. In the Sahel region, Jihadists took advantage of the crisis to recruit new members and to step up their operations. Political and social dissent is likely to escalate in the coming years, as it did in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, especially in countries where governments failed to contain the social impact of the pandemic.

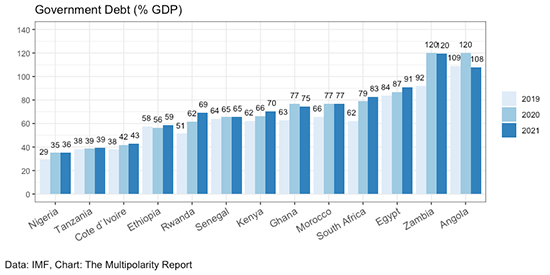

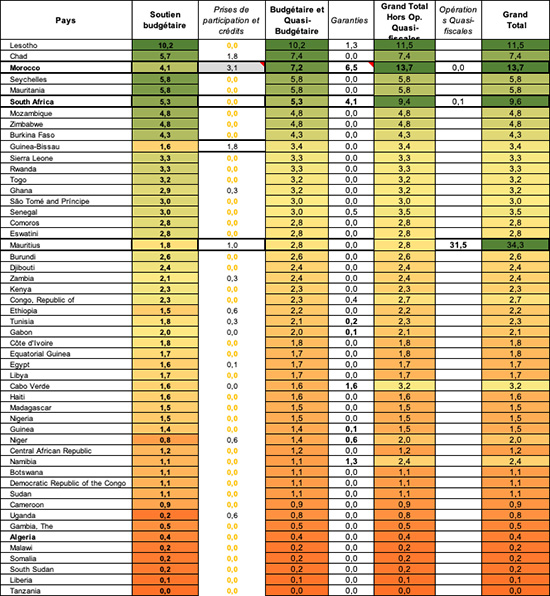

Faced with an unprecedented external shock, African States responded with significant differences in scale and scope. This versatility can be explained in part by unequal fiscal and budgetary rooms for manoeuvre, depending on the macroeconomic and financial situation that existed prior to the crisis (i.e. level of internal and external debt, primary fiscal balance and current account balance, exchange rate regime, etc.). But it also reflects uneven institutional capabilities. In this respect, the responses to the crisis by two emblematic African countries, South Africa and Morocco, are revealing.

The South African Response

In South Africa, where more than 2 million jobs were lost in the second quarter of 2020, the government of Cyril Ramaphosa unveiled a support plan of 500 billion rand, or $30 billion, representing 10% of GDP. The plan extended the existing food aid and targeted cash transfers that covered 11 million South Africans, to an additional 6 million people. The government allocated $6 billion to support investment in infrastructure over the next ten years. Finally, it promised to create 800,000 jobs, a significant part of which would be in the public sector. To finance its programme, the government called on the IMF for a $4.3 billion loan, which was granted in July 2020.

In the short term, this classic Keynesian stimulus policy combining social transfers, infrastructure and public jobs places a significant strain on public finances, with a budget deficit that is expected to rise to 10% of GDP in 2020 and could remain at a high level in the coming years. Even before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the South African economy was suffering from a slowdown in growth, on the backdrop of fiscal austerity, institutional deadlocks and repeated "blackouts" due to under-investment in power generation. If GDP growth does not converge towards the government's target of 3% per year, public debt could exceed 100% of GDP by 2023-2024.

The Moroccan Response

Among African States, Morocco stands out for the speed of its response to the health crisis and the support provided to businesses and households. The Kingdom mobilised nearly 2.8% of GDP to provide a replacement income to its population and to preserve the financial health of businesses, especially of SMEs and sectors most exposed to the crisis (retail trade, hotels and restaurants, tourism, transport). To cover this expenditure, the Moroccan government activated a "precautionary and liquidity line" of 3 billion $ with the IMF. It also issued "Eurobonds" on the international markets for a cumulative amount of $4.2 billion, in the form of two bond issues of €1 billion in September 2020 and $3 billion in December 2020.

For many African countries faced with the impact of the pandemic, reaching out to workers in the informal economy has been a major challenge. In this regard, according to the IMF, "Morocco is a model. The authorities have succeeded in reaching informal workers by combining mobile payments to beneficiaries of the non-contributory health insurance scheme (RAMED, medical insurance scheme) with online monetary assistance applications for others. Households covered by RAMED received a mobile payment of 800 to 1,200 MAD ($80 to $120) depending on the composition of the household."[5] This programme has enabled the protection of 85% of all the households eligible for aid.

In addition to the emphasis placed on the informal economy, the originality of the Moroccan plan lies in the broad scale and scope of unconventional measures: equity investment in private companies, long-term loans and guarantees. The creation of the Mohammed VI investment fund is a central part of this strategy (cf. part III). This public-private Fund is to be endowed with 45 billion MAD, i.e. 3.9% of GDP and co-financed by the State - through a budget allocation of 15 billion MAD (1.3% of GDP) - and by alternative financing to the tune of 30 billion MAD - i.e. 2.6% of GDP. A guarantee envelope of up to 75 billion MAD - or 6.5% of GDP - completes this system. By mid-October 2020, 23,000 companies, 98% of which are SMEs, had benefited from the "Damane Relance" and "Damane Relance VSE" guarantees totalling 27 billion MAD. In addition, more than 50,000 companies benefited from the "Damane Oxygène" guarantee for a total of 18 billion MAD. All in all, the Moroccan recovery plan could mobilise up to 13% of GDP, making it one of the most sustained efforts among African countries, the countries of the North Africa - Middle East (MENA) zone and, more broadly speaking, of all emerging countries.

Frugal innovation and digitisation in response to the pandemic

The concept of frugal innovation was developed by Navi Radjou. It consists of responding to an emerging need in the simplest and most effective way. Africa offers a particularly favourable ground for frugal innovation. In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, African entrepreneurs have shown remarkable agility and innovation. According to a report published by the EIB in July 2020, more than a hundred innovative solutions have been founded and implemented by African entrepreneurs in response to the pandemic. As the EIB notes "some are very simple from a technological point of view, while others are truly innovative. All of them are inventive examples of contributions to the fight against the pandemic." Established Manufacturing companies have contributed to scale these solutions.

In Morocco, "the manufacturing industry has harnessed its capacities, reorienting itself towards the production of protective masks, hydro-alcoholic gel or medical equipment including suits, gowns, mobcaps, overshoes in a short period of time." After satisfying local demand, Moroccan manufacturers started to export their surplus to Europe and other African countries. Morocco also launched the manufacturing of an artificial respirator "Made in Morocco", by leveraging on the production capacities available in the aeronautical sector and by mobilising the Moroccan diaspora.

From Casablanca to Cape Town, the health crisis has led to an awareness of the need to accelerate the digitalisation of the economy and public services. Morocco launched a tracking application called Wiqaytna which has been downloaded more than a million times. FabLab, an innovation hub in Kenya, has developed an application called Msafari, which tracks public transport users. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of data exchange and interoperability between different information systems. The crisis has also accelerated the development of e-commerce. Following the example of Jumia, the African leader in the sector, the platforms have adapted by offering basic necessities and linking local businesses and consumers.

II. Europe-Africa partnership tested by the pandemic

A. The ambition of a new global strategy with Africa

Jean-Claude Juncker's mandate at the head of the European Commission (2014-2019) can be described in retrospect as a "doctrinal reset" for Euro-African relations, raised to the level of a strategic partnership "between equals". The Abidjan summit of November 2017 consolidated this turning point by focusing on youth, investment, and job creation in promising sectors such as digital. The new Commission chaired by Ursula von der Leyen adopted these lines of action, adding other dimensions such as the fight against climate change, the prevention of armed conflict and migration issues.

On March 9 2020, the Commission published a document entitled "Towards a comprehensive strategy with Africa". It states that "the year 2020 will be a turning point in the realisation of our ambition to build an even stronger partnership". The Commission also notes that "Africa's potential is attracting increased interest from many actors on the world stage". It is a thinly veiled reference to China's inevitable position in Africa, but also to the African ambitions of the United States, Russia, Turkey, and the Gulf States. Taking note of this new situation, the Commission proposes to redefine the EU's strategy with Africa based on five thematic partnerships:

1. Green Transition and access to energy

2. Digital Transformation

3. Growth and sustainable jobs

4. Peace and governance

5. Migration and mobility.

The document mentions the need to support private investment and the creation of decent jobs in Africa, but it insists above all on the support that the European Union can provide in regulatory matters, on subjects such as the green transition or digital transformation. Europe thus remains faithful to its image as a "normative empire". The Commission remains extremely elliptical on initiatives with the capacity to transform African economies and accelerate their development. Therefore, the message could very well be blurred thereby losing sight of the strategic nature of the Euro-African partnership. Indeed, while there can be no policy without principles, a statement of principles is not a policy.

Transcontinental integration from the point of view of trade

In this document, the European Union states its readiness to provide "political, technical and financial support to the agreement on the African continental free trade area (for which European aid already increased from €12.5 million in 2014-2017 to €60 million in the period 2018-2020), which represents an absolute priority". And, further on, it states that "cooperation in the area of strategic corridors that facilitate trade and investment within the African continent and between Africa and Europe, and improve the connectivity between the two continents with a view to durability, efficacy and security, will also be strengthened by the long-term perspective of creating a global free trade area linking the two continents."

This commitment to strengthening connectivity between the two continents is welcome - a recommendation made in the study published in July 2019. However, a vision of economic integration dominated by trade, as illustrated by the Commission's insistence on the creation of a free trade area between the two continents, ignores critical dimensions such as the investment in African industrial capabilities and technology transfers.

B. An agenda in turmoil because of the pandemic

An emergency response focused on the fight against the pandemic

On 8 April 2020, the European Union launched emergency measures under the tag "Team Europe", in support of its partners to counter the pandemic. As of November 2020, the total amount of pledges announced by "Team Europe" reached €38.5 billion, of which 50% had already been disbursed. The assistance was meant to respond to humanitarian needs, to strengthen local health systems and to deal with the socio-economic consequences of the pandemic (€26.63 billion).

Together with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation the EU is the biggest donor to the GAVI COVAX, initiative co-led by the Global Alliance for Vaccines (Gavi) and the WHO, which aims to ensure fair and equitable access to Cobvid-19 vaccines worldwide[6]. It has been endowed with $2 billion facility to fund one billion doses of Covid-19 vaccine for low- and middle-income countries. According to the GAVI, at least $5 billion more is required in 2021. Beyond securing vaccine supply, distributing vaccines in countries with predominantly rural populations is a logistical challenge. For example, the vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna require cold storage up to the "last mile". On a more geopolitical level, the EU has to cope with unilateral initiatives from China, India and Russia, which have offered their own anti-COVID vaccinations to the countries of Africa, bypassing the GAVI COVAX mechanism.

The Conclusions of the June 2020 Council

On 30 June the Council published a document re-stating its conclusions on Africa, which broadly endorsed the Commission's strategy while refocusing the priorities of the Euro-African partnership around four themes: 1°) promotion of multilateralism; 2°) peace, security and stability; 3°) inclusive and sustainable development; 4°) sustainable economic growth. The Council further highlighted the support given by the European Union to Africa in the fight against the pandemic. Finally, it reiterated its call for African debt relief.

A minimal overhaul of the EU-ACP Partnership (Post-Cotonou)

The longstanding negotiation process between the EU and ACP countries - including Africa, Caribbean and Pacific countries - on a new "post-Cotonou" partnership was brought to a conclusion on 4 December 2020. Nevertheless, the changes are minimal. The new agreement comprises a "common ground" which sets out the strategic priority areas in which both parties intend to work together: human rights, democracy and governance; peace and security; human and social development; environmental sustainability and climate change; inclusive and sustainable economic growth and development; migration and mobility. The new agreement associates three regional protocols (Africa, Caribbean, Pacific) to this common base. According to the Commission's press release, "Governance specific to the regional protocols will be used to manage and steer relations with the European Union and the different regions concerned, in particular through joint parliamentary committees". From a financial point of view, the integration of the European Development Fund (EDF), through the Neighbourhood, Development Cooperation and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI), as part of the multi-annual budgetary plan 2021-2027, had already taken this regionalisation into account. Apart from this change in governance, the real concession taken by the Union with this agreement concerns the obligation to readmit illegal migrants to their country of origin.

The EU-ACP Partnership Agreement remains the legal framework that structures the European Union's relations with Sub-Saharan Africa. Within this framework, development-related issues are addressed through the NDICI and the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD+). Trade relations are defined through Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) between the European Union and the different African sub-regions. North African countries are treated separately within the framework of the association agreements reserved for the neighbourhood countries. The Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Employment and the Communication "Towards a comprehensive strategy with Africa" are political and economic strategies, subject to change. The focus on partnership between continents is thus hampered by a complex web of institutional hurdles, and by overlapping thematic and geographical priorities which the European Union struggles to clarify.

III. Proposals for a Renew Euro-African Partnership

A. Clear priorities and inspirational projects

A new governance structure

In a column published on 4 December 2020, Carlos Lopes, the High Representative of the African Union (AU) for the partnership with Europe insisted on the need to turn the "partnership between equals" into a reality. In his view, "both sides must abandon the fragmented and unbalanced approach of the past and work towards the creation of an effective joint governance mechanism." To support this, one could imagine the establishment of a permanent EU-AU Commission. The European Union should also rely more on the institutions of the African Union - such as the African Development Agency and the African Peer Review Mechanism - and make more sustained references to the latter's "Agenda 2063". For its part, if the African Union is to be considered as an equal to the European Union, it should achieve its financial autonomy and no longer depend on grants from international donors.

A partnership based on what Africans really need

To increase the resilience of African States to crises, the upgrading of health systems and the expansion of social protection systems are necessary. Over the past three decades, dominated by the "Washington Consensus", social protection issues have been relegated to the backburner. However, numerous studies show that a universal social protection system is the fundamental basis for inclusive development. The European Union, which has an unparalleled experience in this area, could make it available to its African partners. This effort is particularly necessary to reduce the burden of the informal economy and to increase the productivity of African workers. In Morocco for example, King Mohammed VI, in his Speech from the Throne on 29 July 2020, called for the establishment of universal social security coverage by 2025, including compulsory health insurance, family allowances, unemployment insurance and retirement pensions[7].

The Covid-19 pandemic has served as a catalyst and accelerator for change in the global economy. The European Union must go beyond declarations of intent, by proposing major inspirational projects to Africans: a Marshall Plan for infrastructures, an agricultural alliance, an industrial and technological alliance and, finally, a digital alliance. In a previous policy brief, we have put forward our proposals to significantly increase intra-African and Euro-African connectivity, in view of binding the two continents more firmly to each other, in accordance with the wishes expressed by Robert Schuman several decades ago. We have also developed the idea of a Euro-African industrial alliance, based on the cumulation of rules of origin, which allows trade to be used for industrial co-production[8]. Finally, in the light of this crisis, digitalization no longer appears to be a "nice have" just for rich countries but a "must have", designed to ensure the resilience and agility of local, national and continental production and exchange systems.

Mitigating and adapting to climate change

The issue of climate change must obviously be one of the partnership's priorities. The economic, social and environmental aspects of development are indeed inextricably linked, as shown by the conflicts between sedentary farmers and semi-sedentary livestock farmers, which have been caused by droughts and other extreme weather events. The agricultural sector, on which more than two-thirds of Africans depend directly or indirectly, is particularly exposed to these phenomena, which accelerate migration and provide fertile ground for terrorist movements, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria. In this field, Europe should go beyond declarations of intent. It could encourage the creation of Euro-African agro-industrial chains from upstream agriculture to downstream industry - integrating food crops, long neglected in the neo-liberal doctrine of development. This would help to fix local populations and bring migration policies into line with development aid policies.

B. Adapted finances

Restructuring the African debt

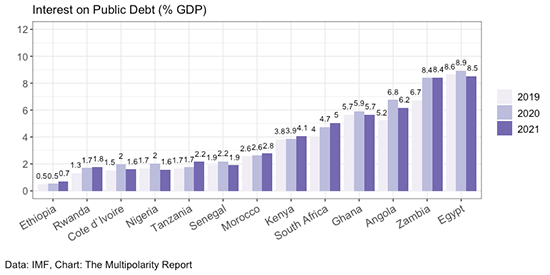

The economic recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic will increase the burden of debt on some African States. Given the pandemic, the G20 States decided in April 2020 to establish a moratorium on servicing the public debt, due on account of 2020, by low-income States most of whom are to be found in Africa. The moratorium has enabled 46 low-income countries to benefit from payment deferrals totalling $5.3 billion (out of nearly $30 billion in interest due in 2020). An agreement signed in November 2020 required the involvement of private creditors in any future restructuring of poor countries' debt, based on the principle of "comparability of treatment". Thus, a debtor wishing to obtain a restructuring of its public debt will have to demand the same treatment from its private creditors. In addition, the IMF would be the "linchpin" of the system, since countries requesting debt restructuring would have to comply with an adjustment programme to ensure the sustainability of their debt. De facto, these conditions limit the scope of the initiative. Several countries have preferred not to use them in order to avoid stigmatisation by financial markets.

In addition to this the strategy of some creditor countries such as China must be taken into account. Indeed, according to a World Bank report, China holds almost two-thirds of the bilateral debt of low-income countries. However, Beijing has always preferred the conversion of debt into investments to the simple cancellation of the latter.

European countries could take a unilateral initiative by converting part of the African public debt into investments dedicated to the green or digital transition. This type of arrangement has already been used on a small scale, by countries like the Seychelles. In April 2020, a group of African intellectuals and leaders proposed the creation of an African Debt Restructuring Fund that would swap old debt owed to private investors for bonds guaranteed by the G20 States - on the model of the "Brady Bonds"[9]. In all events, the ethical uncertainty that would result from indiscriminate treatment between unthrifty and virtuous States should be avoided.

The concept of mixed financing or "blended finance"

The concept of "mixed or blended finance" - consists in obtaining a leverage effect by combining public resources and private funding within a package designed to finance investment projects. It became popular in Europe with the "Juncker plan". Designed in response to the consequences of the 2008 financial crisis and the euro crisis, the Plan proposed to support private investment of up to €315 billion, based on a budget commitment ten times smaller. The objective was reached by 2018. It was raised to €500 billion by 2020. The European funds for strategic investments is the financial pillar of this plan. It is managed by the EIB, which benefits from a European Union budgetary guarantee in the form of a "first-loss protection".

The External Investment Plan, adopted in September 2017, is the counterpart of the Juncker Plan to finance projects outside the European Union. Over the period 2017-2020 it was provided with 4.6 billion € in own funds - 3.1 billion for blended finance and 1.5 billion for guarantees - to fund investments to a total of up to 46 billion €. This mechanism has been renewed and enhanced for the period 2021-2027, with a total strike force of 60 billion on the basis of €6 billion of equity capital[10] The European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD), the main financial instrument of the external investment plan, was created by merging two regional "blended finance" mechanisms in operation since 2007: the Investment Platform for Africa (IPA) and the Neighbourhood Investment Platform (NIP)[11]. Since its creation, the blended financing granted by the latter has been "channelled" through five major institutions which have shared 93% of the total envelope: EIB (26.3%), AFD (19.5%), ADB (18.1%), KFW (15%) and EBRD (14.7%).

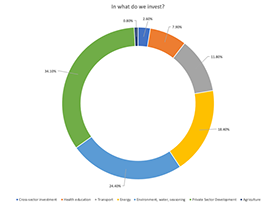

Sectoral Distribution of funds granted by the EFSD

Neighbouring country (East and South) | Sub-Saharan Africa

Source : 2019 Operational Report EFSD.

Use of innovative finance: the experience in Morocco

The Moroccan experience in innovative financing is particularly interesting and could inspire other African countries in their relations with Europe. It should be recalled that Morocco has a long tradition of cooperation with the European Union, its Member States and its agencies. The EIB has been active in Morocco since 1979. To date, it has financed 125 projects totalling EUR 8 billion €[12]. It was particularly successful in financing the Casablanca tramway and the Noor solar energy complex in Ouarzazate. Morocco has also subscribed to the EBRD's capital since its creation in 1991. Following the "Arab Spring" of 2011, the scope of this multilateral development bank was extended to the countries of the southern shore of the Mediterranean. In 2015, it developed a specific country strategy for Morocco. At the end of November 2020, the EBRD supported 73 projects in Morocco, disbursing more than €1.5 billion of financing, almost half of which (47%) went to the private sector. It should also be recalled that Morocco is the French Development Agency's lead country, with a growing commitment to the private sector through lines of credit for SMEs and equity investments via Proparco, AFD's subsidiary dedicated to "impact investments".

An example of blended financing:

The Moroccan Sustainable Energy Financing Line (MORSEFF)

With a total of €110 million, MorSEFF is the sustainable energy financing line for private Moroccan companies. Supported by the European Union and developed by the EBRD in cooperation with the EIB, AFD and KfW, it helps Moroccan companies access loans for the acquisition of equipment or the implementation of energy efficiency or renewable energy projects, with an investment grant representing 10% of the credit granted, as well as free technical assistance for project evaluation, implementation and verification. This scheme is distributed locally by partner banks, BMCE Bank (and its subsidiary Maghrebail) and Banque Populaire (and its subsidiary Maroc Leasing). The investment grant is financed through grants from the European Union's Neighbourhood Investment Facility (NIF) and technical assistance through grants from the NIF and the South East Mediterranean Multi-Donor Fund (SEMED)* managed by the EBRD.

More recently, the Mohammed VI Fund for Investment, created within the framework of the Moroccan post-Covid 19 recovery plan, is emblematic of a new generation of innovative funds. Combining conventional resources and innovative financing, in particular "blended financing", its objective is to finance major investment projects within the framework of public-private partnerships (PPPs). It aims to finance local companies through long-term loans and equity participation in the capital of these companies, through sectoral or thematic funds. Its activities are expected to be coordinated with the newly created National Agency for the Management of State Shareholdings (Agence nationale pour la gestion des participations de l'État).

The operational management of this "Fund of Funds" is to be entrusted to the CDG Group (Caisse de Dépôt et de Gestion), via its subsidiary CDG Capital. The originality of the Mohammed VI Fund is based on the complementarity between the economic logic of "Private equity" and the social logic of "Public equity"[13]. This hybridization is reflected in the fund's liabilities. Indeed, of the 45 billion MAD planned to finance it, only one third - or 15 billion - comes from a budgetary allocation. The remaining two-thirds, i.e. 30 billion, are to come from non-budgetary financing: investment subsidies deployed by multilateral and bilateral development banks, co-investments by national institutional investors (pension funds, insurance companies) or by private funds specialising in impact investing and sustainable financing (Green Finance).

Other African countries have set up public-private investment vehicles, such as Senegal where a Sovereign Fund for Strategic Investments ("Fonsis") was created in 2012. On the basis of its own funds, Fonsis' goal is to "raise additional funds through leverage and investment in the real economy" to "create flagship Senegalese companies in certain sectors to be able to attract local talent and the diaspora while creating wealth for the shareholder State and future generations". The primary objective of these funds is therefore to invest in the local economy. In this, they differ from the funds created by the States exporting raw materials - such as the Sovereign Wealth Funds of Ghana, Nigeria or Equatorial Guinea - whose objective is to invest surplus savings on the international markets.

The case for joint partnerships

Finally, the European Union's engagement in Africa could take the form of joint partnerships, based on regional hubs. Casablanca, Abidjan, Johannesburg and Nairobi appear in this respect to be focal points that might serve as financial and operational relays for a transcontinental partnership strategy. Initiatives in this sense already exist. In 2018 a strategic agreement was signed between the Moroccan group Banque Centrale Populaire (BCP) and Proparco, AFD Group's private sector subsidiary. Via this agreement, Proparco is due to support the development of the BCP in Africa. The value of these partnerships lies in the more efficient mobilization of financial resources and their increased leverage.

The United States, which is developing a targeted partnership strategy with a few countries on the African continent, has clearly understood the value of such mechanisms. At the end of December 2020, the agency USAID announced that Morocco was to become its regional centre for North Africa. Its financial branch, the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) signed an investment memorandum to turn Morocco into a hub for its investments in Sub-Saharan Africa, with an envelope of 3 billion $, as part of the "Prosper Africa" initiative. Each dollar granted through this programme should facilitate the leverage effect of private investment.

***

The Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated a resilience that has disproved even the most pessimistic predictions about the capacity of African States to manage this crisis, even though the speed and effectiveness of policies implemented in this regard vary greatly from one country to another. Nevertheless, the continent has been severely affected by the economic and social repercussions of this unprecedented external shock, which has highlighted the intrinsic vulnerabilities associated with economies with a narrow productive base and a high degree of informality, heavily dependent on global demand and international capital. In response to the crisis, some African States have applied conventional recipes. This is the case of South Africa, the continent's most advanced economy, whose fiscal balance has deteriorated on the backdrop of prevailing economic stagnation and institutional deadlocks. In contrast, Morocco has responded by mobilising an arsenal of unconventional measures, which has helped it support local businesses and households, while limiting the impact of the stimulus plan on public finances.

EU-Africa relations have been tested by this multidimensional crisis which has upset political priorities and agendas. Despite laudable intentions, as formulated in the strategy of "Partnership between equals" unveiled by the European Commission in March 2020, one of the only achievements of the year has been the renewal of the "EU-ACP countries" partnership, which recognised the specificity - and centrality - of the African continent within the ACP grouping. For the rest, it is important to go beyond declarations of intent to propose a more engaging "narrative" supported by flagship projects that respond to African needs. From industrial co-production, to digitalisation and the fight against climate change, the European Union must reaffirm its role as Africa's leading partner, in a context marked by growing rivalry between major powers. To do so, it should encourage the international community to achieve debt restructuring for the most fragile African countries, while relying on the most virtuous States. The use of "blended financing" is a promising avenue in this regard. Morocco's innovative approach could serve as a matrix for the entire Europe-Africa partnership. Hence, drawing on the experience of Moroccan companies and financial institutions on the African continent, the European Union could develop an African strategy more in line with the expectations of local stakeholders, and with the realities on the ground.

ANNEXES

Budgetary and quasi-budgetary support schemes deployed by African States (% GDP)

[1] Of particular concern is the discovery and spread in South Africa of a particularly contagious mutant variant of COVID-19. A race against time is underway in the African countries most affected by the pandemic to vaccinate their populations.

[2] Nevertheless, the population density in certain large African cities reaches and sometimes exceeds that of European, American or Asian ones. Some districts of Johannesburg have more than 50,000 inhabitants per square kilometre.

[3] Camille Belsoeur, L'expérience d'Ebola a aidé certains pays africains à agir efficacement face au Covid-19, Slate.fr, 28 May 2020. (The experience of Ebola helped some African countries act effectively against Covid-19)

[4] Created by researchers of the Blavatnik School of Government (University of Oxford).

[5] IMF, Idem.

[6] The Union has committed €100 million to the GAVI COVAX initiative through Team Europe, to which are added €400 million in guarantees provided by the EIB, as well as the individual commitments of France (e100 million) and Spain (€50 million).

[7] In this context a merger is planned between the RAMED health insurance system devoted to independent workers, the TAYSSIR measure for conditioned money transfers and social common law protection

[8] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-522-fr.pdf

[9] The latter collateralised by American Treasury bonds were issued thirty years ago to restructure the Latin-American debt

[10] For more details regarding these mechanisms European Issue N°522 - Fondation Robert Schuman (robert-schuman.eu)

[11] An independent assessment of the EFSD undertaken in 2019 concluded that this fund was "highly adapted" to the investment financing requirements of the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and the EU Neighbourhood.

[12] As part of the fight against the coronavirus pandemic, the EIB has granted Morocco emergency financing of €200 million, of which a first tranche of €100 million was disbursed in August 2020. This financing is part of the Moroccan National Pandemic Response Plan of COVID 19 and Team Europe. The EIB has also granted a credit line of €200 million to Crédit Agricole du Maroc (CAM) a €200 million credit agreement aimed at strengthening support for Moroccan companies in the agricultural and bio-economy sectors.

[13] This was already the case with the Hassan II Fund for economic and social development created in the year 2000 to support the large industrial investment projects within the Kingdom - following the example of the Renault factory in Tangiers. Nevertheless, the Mohammed VI Fund goes further through its "fund of funds" logic.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :