Freedom, security and justice

Eric Maurice,

Thibault Besnier,

Marianne Lazarovici

-

Available versions :

EN

Eric Maurice

Thibault Besnier

Marianne Lazarovici

1. Closure of the borders, an emergency response

Since the creation of the Schengen area in 1995, internal borders between Member States have been closed only occasionally, and by one or a few States at a time. In most cases, the aim has been to re-establish checks for short periods to ensure the smooth running of political events or mass gatherings. In other cases, the decision to re-establish controls have come in the wake of serious or exceptional events - the 2015 attacks in France or the mass arrival of migrants in the Union in the same year.

With the Covid-19 crisis, the re-establishment of internal border controls was generalised and decided in haste. In the space of two weeks, half of the Member States of the Union introduced controls on all or part of their borders with their neighbours. Some have also imposed entry bans on foreigners.

A domino effect

As the number of cases of coronavirus gradually increased in various Member States, the question of border closures arose as early as February. On February 24th, the European Commissioner for Crisis Management, Janez Lenarcic, insisted on the fact that possible measures on the internal borders should be based on a credible risk assessment and proportionate, scientific evidence, taken in coordination with the other Member States, stating that "there are no other reasons why there should be travel restrictions or border controls".

Everything gathered pace on March 10th and 11th, when the Italian Prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, decreed the confinement of the population throughout Italy and the closure of all shops, with the exception of grocery stores and pharmacies. At that time, Italy had 12,462 COVID-19 cases of the 22,000 recorded in Europe, and 827 deaths.

On March 11th, Austria and Slovenia introduced controls on their borders with Italy, and Malta imposed restrictions on travel to and from Italy and several other European States. On March 12th, Hungary reintroduced border controls with Slovenia and Austria. On March 13th, Switzerland re-established border controls with Italy, and Denmark restricted the crossing of all its borders. On March 14th, Austria extended border controls with Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Then, like dominos, restrictions on internal borders then quickly came in succession mainly in Central and Eastern Europe. On March 16th, Germany restricted the crossing of its borders with France, Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg and Switzerland to Controls on all borders and suspension of international links (except freight).

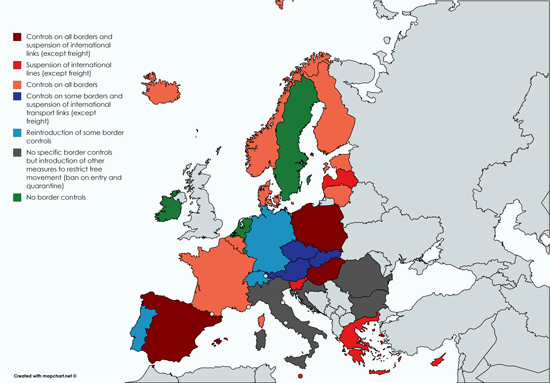

Restrictions introduced by the Member States of the Union and the Schengen Area

As of March 30th, 16 Schengen countries had reintroduced or extended controls on least one of their borders: Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Estonia, Portugal, Spain, Finland, Belgium, Slovakia and France[1], as well as Switzerland and Norway. Iceland reintroduced controls in April.

All States, with few exceptions, including France and Italy, also introduced an entry ban for certain foreigners. In addition, a large number of States suspended air, rail and bus connections with all or some States, mainly Italy, Austria, Spain, France and Germany. Greece, which does not share a land border with any other Schengen State, suspended all commercial flights with Italy, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, and allowed connections with Germany only at Athens airport. Malta suspended air links to Italy, Spain, France, Germany and Switzerland. Only a few states such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands have left their borders relatively open.

Italy, for its part, did not impose border controls or suspend air links, but imposed quarantine on people coming from other EU countries and banned the passage of cross-border workers. The non-Schengen Member States also took restrictive measures. Bulgaria banned people from EU countries considered to be most at risk from entering its territory, Romania suspended bus connections with several countries, and Cyprus suspended all passenger flights.

Damage Control

As a result, free movement in the Union was virtually suspended within a few days. These restrictions have led to various problems, in particular major disruptions for cross-border workers and the trade in goods and services.

The primary effect of the re-establishment of border controls has been to disrupt business supply chains by delaying the arrival of goods and services for consumption and production. Delays on the borders resulted in a slowing of the transport of medical and protective equipment, at a time when many Member States were desperately short of such equipment.

Cross-border workers, whose number is estimated at 1.9 million in the Schengen Area, as well as mobile workers, also experienced difficulties. Businesses and public services employing cross-border workers have found themselves short of labour, as have employers of seasonal workers, particularly in the agricultural sector. Many cross-border carers may have experienced difficulties and delays on their way to work, especially between Luxembourg and France, Belgium and Germany.

This situation forced the Commission to take action on March 16th. It conceded that "in an extremely critical situation, a Member State can identify a need to reintroduce border controls", but recalled that checks should be carried out "in a proportionate manner and with due regard for the health of the persons concerned".

For the Commission, the sudden closure of borders jeopardised the proper functioning of the single market. In the guidelines, followed a few days later by recommendations to the Member States, it attempted to limit the disruption created by the multiplication of controls and to promote cooperation and the exchange of information between States. It asked for the introduction of special lanes at crossing points to limit road hauliers' waiting time, as well as lighter health screening procedures and checks for lorry drivers.

Regarding cross-border workers it listed the 17 professional categories which should be given priority at border crossing-points, the first of which were medical and paramedical staff, emergency and security services, employees of the transport and infrastructure sectors.

While the pandemic had not reached its peak and its economic impact was beginning to become apparent, the Commission's response reflected awareness, but was limited by the urgency of the issue. It was only a month later that it began to consider reopening borders and returning to normalcy.

A return to normal?

"Each country will decide alone regarding the opening and under which circumstances", said the Belgian Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès on June 3rd. The declaration is a good illustration of the mindset in which States have been operating, three months after the suspension of free movement. While the Member States had undertaken to reopen their borders in a coordinated manner, the process seems to be repeating, in a reversed and much slower manner, the disorganization that prevailed when controls were reintroduced.

On May 13th, the Commission published recommendations for the resumption of transport and tourism, and the principles for a "phased and coordinated approach" of the re-establishment of free-movement.

The main criterion for the lifting of restrictions throughout the Union is the favourable evolution of the epidemiological situation. Failing this, "travel restrictions and border controls should be lifted for regions, areas and Member States with a positively evolving and sufficiently similar epidemiological situation". The assurance that a resurgence of the virus could be controlled by a sufficient number of tests and hospital beds, as well as by adequate surveillance and tracing capacities, must also be taken into account.

To prevent the risk of regional "mini-Schengen" areas further fragmenting the area of free movement, the Commission insisted that the lifting of controls should not be decided on the basis of the geographical proximity of neighbouring States but should be "based on comparable epidemiological situations and implementation of health-related guidance in regions, regardless of their proximity".

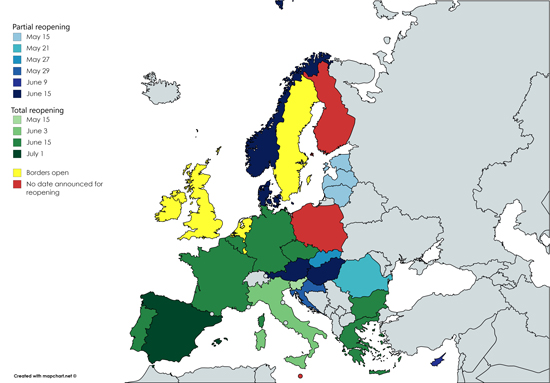

The three Baltic States opened a shared area as of May 15th, whilst maintaining restrictions vis-à-vis the other Member States.

The timetable for the re-opening of the borders

France and Germany, notably by way of the presidents of the Assemblée nationale and the Bundestag, Richard Ferrand and Wolfgang Schäuble, have insisted on the reopening of the borders. But not all governments, which hover between the need to revive the economy, the willingness to show results to public opinion and the reluctance to open up their territory again, are not all taking the common interest into account. Hence some countries have considered introducing tourist corridors, an idea rejected by Italy and which was not followed up.

While most states have committed to reopening their borders on June 15th, European Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson said on June 5th that the health and political conditions were in place for a return to "full functioning of the Schengen area and the free movement of citizens no later than the end of June". The Commissioner and the 27 Home Affairs ministers agreed to extend the closure of the external borders until June 30th.

The reopening of the external borders remains a prerogative of the Member States. Its coordinated implementation will be crucial to prevent governments that do not wish to reopen the borders from closing their territory again to protect themselves from travellers from third countries that have been accepted in another Schengen state.

The way in which the Schengen area and the single market return to normal functioning from June 15th onwards will partly determine the Union's economic recovery. It will also determine the future of the principle of free movement, which has been undermined by the crisis.

2. Freedom of movement in parenthesis

The partial or total closure of national borders has developed alongside the introduction of health measures in the Member States. It could therefore be considered as a simple element, or even a consequence, of the great trend towards lockdown. However, it is based on a different logic and raises legal and political questions about the future of freedom of movement in the Union.

A fundamental principle

Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union provides that the "The Union shall offer its citizens an area of freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of persons is ensured." Article 21 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) article 45 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights stipulates that "every citizen of the Union shall have the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States".

Title IV of the TFEU as a whole governs the free movement of persons, services and capital. In Title V, devoted to the area of freedom, security and justice, Article 77 states that "the Union shall develop a policy with a view to ensuring the absence of any controls on persons, whatever their nationality, when crossing internal borders."

An infringed directive

The "primary and individual right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States" is implemented by the directive on free movement adopted in 2004. The latter allows Member States to "restrict the freedom of movement and residence of a Union citizen or a member of his or her family, irrespective of nationality, on grounds of public policy, public security or public health" (Article 27), and specifies that "the only diseases justifying measures restricting freedom of movement shall be the diseases with epidemic potential" as defined by the World Health Organisation (Article 29).

The reintroduction of controls and, even more so, the suspension of international travel and the ban on entry into the territory of certain Member States imposed on entire categories of the population have not respected the principle of individualisation of the decision referred to in Article 27, nor the principle of non-discrimination between European citizens. But Article 29, which is more general in scope, leaves room for interpretation of the obligations of the States. The questioning of the free movement of the coronavirus at the time does not therefore appear to be in direct breach of European legislation.

However, certain situations have led to clear infringements of the fundamental right of Europeans to move freely, in particular the right to return to their country.

For several days in March, citizens from the Baltic countries - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania - were blocked by the Polish authorities on the German border before being transported through Poland under police escort or shipped home on ferries dispatched by their governments. A similar situation occurred on the Austro-Hungarian border with Romanian citizens who were trying to go home.

The Schengen Code circumvented

Member States have also circumvented important elements of the rules of the area of free movement.

The Schengen Code generally provides for the reintroduction of checks on internal borders "only as a last resort", with a minimum of four weeks' prior notification. However, in the event of a "serious threat to public policy or internal security" requiring "immediate action", Member States may re-establish border checks, without prior notice but with immediate notification, for a period of 10 days, renewable for up to 2 months (Article 28). It is this provision that States have invoked to close their borders as they faced a sudden pandemic that threatened health systems.

However, in an emergency, the Member States have dispensed with the obligation to assess "the likely impact of such a measure on the free movement of persons" within the Schengen area (Article 26), and have disregarded the Commission's recommendations for proportional and coordinated measures.

A dangerous precedent

The Schengen Code does not explicitly provide for the case of a pandemic developing randomly on European territory, nor a fortiori for the lockdown of the Union's populations. The legal basis on which the Member States have decided to reintroduce border controls and prohibit the entry of certain persons into their territory is therefore unclear and sets a precedent for the interpretation of the law according to the situations and interests of the States, outside the agreed framework.

In previous challenges to free movement in 2015-2016, 8 Member States reintroduced border controls, compared with 15 during the coronavirus pandemic. With each crisis the use of border closures is becoming more widespread, with increasingly looser compliance to the rules.

The reintroduction of controls on internal borders, even if it is in theory supervised, is the jurisdiction of the States. The Commission has only been able to note the disruption caused and try to remedy it from an economic point of view, and not from a fundamental rights point of view. It has simply observed that "in an extremely critical situation, a Member State can identify a need to reintroduce border controls as a reaction to the risk set by a contagious disease."

In the roadmap published jointly with the President of the European Council, Charles Michel on April 15th, The President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, assured that the Commission would continue to analyse the proportionality of the measures taken and would ask for the lifting of those it considered disproportionate, "especially when they have an impact on the single market". However, no assessment seems to have been published, nor any request addressed to Member States.

The proportionality of controls and travel suspensions, in the context of company closures, seems difficult to assess since Europeans have not been in a position to travel anyway. This argument, however, ignores the fact that for many Europeans individual travel was not limited to a particular distance, as was the case in Italy, Spain or France, and that health measures taken at local or national level might well have made it possible to avoid border closures.

From this point of view, it is difficult to defend under European law that the "serious threat to public order or internal security" required certain States to impose generalised restrictions on freedom of movement from other States, ignoring the individualisation of the decision required by the texts, while no equivalent restriction on movement was in force on the territory. This difference in approach to internal and external mobility raises a legal problem and sets another precedent in terms of civil liberties in Europe.

In addition, the Schengen Code provides for the use of border controls for security purposes. Decided in the context of a pandemic, it has been used as an adjunct to national, uncoordinated health strategies, without justification by the Member States or the Commission's evaluation of this correlation. While it can be explained in view of the situation and the need for governments to reassure public opinion, the suspension of free movement thus raises serious legal and political questions for the future.

And now

On expiry of the maximum two-month period provided for in Article 28 of the Schengen Code, the Member States once again circumvented the rule and extended the checks, this time invoking Article 25, which allows them to maintain the measures for 30 days initially and up to two years with further authorised renewals. This change of legal basis was made without any further impact assessment or coordination between States. Moreover, the notion of "last resort", although required by the text, cannot not be argued since the pandemic was on the wane and the end of lockdown was under way.

While the Commission and the Member States are trying to organise a return to normal free movement, this remains suspended for as long as the Member States can invoke the current procedure.

Since its conception, the Schengen area has been based on a balance, between the opening of internal borders and the control of external borders. The "exceptional circumstances when the overall functioning is put at risk", which allow the Council to recommend to one or more Member States the reintroduction of internal border controls (Article 29 of the Schengen Code), refer moreover only to "serious deficiencies" in the management of the external border. There is no provision for the Council or the Commission to coordinate such a procedure in the event of any other crisis situation, such as the current pandemic.

In 2015-2016, it was because of this intrinsic balance that the Commission was able to rely on the Schengen Code to act, despite the fait accompli of the suspension of asylum rules by Germany and the subsequent reintroduction of border controls by several States. The coronavirus crisis shows that it is powerless when States act of their own accord in situations independent of migration policy. It is significant in this respect that the main measure taken by the Commission to prevent further disruption in March was the closure of the external borders, without it being able to explain the justification of this in terms of public health.

In the future any potential crisis, health or otherwise, should be subject to a specific legal framework. In a resolution adopted on 4th June, The European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs also called on the Commission to propose ways of ensuring "truly European governance" of the Schengen area.

3. Movement, an economic issue

One of the fundamental achievements of the European Union, around which European policies and programmes are structured, is the set of "four freedoms": the free movement of people, capital, services and goods. These freedoms form the core of the two achievements affected by the coronavirus crisis, the single market and the Schengen area, the proper functioning of which is essential to the European economy.

The benefits of free movement

In a study published in April, The European Central Bank estimated that between its establishment in 1993 and the financial crisis of 2008, the single market has generated a growth gain of 22% for Member States. The CEPII, an analysis centre under the authority of the French Prime Minister, calculated that in 2018 bilateral trade within the single market is three times the size it would be if it were simply a part of a traditional regional trade agreement.

Free movement of workers also brings economic gains. According to the EPRS, the European Parliament research centre, the wealth creation attributable to active European citizens working in a Member State other than their country of origin was estimated at €106 billion in 2017, and a figure that would be much higher if cross-border and posted workers were to be taken into account.

The single market and the Schengen area are therefore important sources of revenue and growth for the Union and its Member States. Putting them on the back burner also tends to create major economic disruption in addition to that created by the coronavirus and lockdown measures.

The cost of lockdown

In its forecasts published in May, the Commission estimated the drop in the Union's GDP due to the pandemic and the almost total halt brought to activity which it caused in 2020 at -7.4%. If the lockdown measures that are gradually being lifted are not reintroduced and a massive and coordinated recovery plan is launched quickly, growth in 2021 could rebound to +6%. But GDP would still be 3% below the anticipated level, and the employment rate 1% lower, with an expected unemployment rate of 9.5% of the working population. The shock will be different from one Member State to another, since each have different economies.

Two "ecosystems" that have been badly affected by the pandemic illustrate the economic effects of border closures: mobility and tourism.

Mobility, which includes all the players in the transport and automotive sectors, including 1.4 million companies in the automotive sector, accounts for 5% of the Union's value added. 45.3% of its production is based on cross-border value chains, which have been greatly destabilised by the lockdown and reintroduction of border controls. These disruptions in production chains and the fall in demand for cars and transport are contributing to losses that the Commission estimates at between €91 and €152 billion in 2020.

The tourism sector, which by definition depends on freedom of movement, accounts for 10% of European GDP, and up to 20-25% of GDP for Greece and Croatia. Its losses could amount to €171-285 billion this year. This explains why the reopening of borders has been designed mainly for the summer season, rather than to address issues of civil liberties.

In March, the month in which the lockdown measures, border controls and travel restrictions were introduced, intra-euro area trade collapsed by 12.1% compared to March 2019, and intra-EU trade by 7.9%. For the first quarter, the year-on-year decrease was 4.7% and 2.4% respectively. The figures for April and May will certainly be even more unfavourable, while recovery will depend on the pace and conditions of the reopening of borders and the resumption of transport.

A successful reopening of the borders

A smooth functioning of the Schengen area in the coming months is therefore essential to support the recovery of the highly integrated European economy. A lack of coordination, or the reintroduction of controls, even on a smaller scale, would cancel out some of the benefits of the resumption of production.

However, it is difficult to put a figure on the cost of the infringements of freedom of movement, if they were to be prolonged, largely because it would depend on the number of borders affected, the flows crossing those borders and the duration of the measures. In 2016, the Commission estimated that the total reintroduction of border controls would lead to directs costs of between 5 and 18 billion € per year. It pointed out that "these costs would be concentrated on certain actors and regions but would inevitably impact the EU economy as a whole".

A study by France Stratégie in 2016 estimated that the end of the Schengen area would mean a 10-20% drop in trade between Member States and a shortfall of more than €100 billion over a decade, but the reduction in labour mobility, with the fall in investment and financial trade expected to have a further impact, is however difficult to quantify. The costs depend very much on the method of control: spontaneous, random or more frequent controls.

Immediate issues at stake

The full recovery of economic activity in Europe depends on the reopening of internal borders and the restoration of the 4 freedoms, in particular those of people and goods. In most sectors of European agriculture for example, the labour force is mainly made up of European seasonal workers. Many harvests could not be harvested due to lockdown and the obstruction imposed on European workers.

The re-establishment of transnational freight transport is also essential. Many value chains have become europeanised, i.e. aligned with several countries across the Union. Border closures have disrupted them and priority border corridors for truckers have not eliminated delays due to controls.

Finally, the smooth functioning of the Schengen area and of the single market will be a key element to the success of the European recovery plan, based on a massive borrowing by the Commission (€750 billion according to the proposal still to be approved by Member States and Parliament). In addition to the need to restore transnational activity and value chains if the full benefits of the collective effort are to be reaped, the Member States' commitment to free movement will be an indicator for the markets, which will be called upon for the loan, of the stability of the euro area and the European Union.

***

Like many of the crises the Union has faced in its history, the coronavirus crisis has shown the political and legal limits of its integration, while at the same time providing an opportunity to explore new paths in response out of necessity.

A blueprint for a Europe of health has been implemented to make up for the shortcomings of the Member States; and awareness is developing regarding the need to ensure the strategic autonomy of the European Union in the economic field and, above all, the taboo surrounding the mutualisation of debt and financial transfers is being lifted.

The crisis has demonstrated that free movement, a fundamental element of the acquis communautaire, is not an intangible principle even when the issue does not concern migration. This event should also lead the European Union to rethink and strengthen the functioning of the Schengen area by clarifying the legal framework and providing the institutions with the tools to enforce it, in the interests of the Union, its values and the rights of its citizens.

[1] In chronological order of notification to the European Commission. It was only on April 8 that Slovakia notified the checks introduced on March 13. France notified the Commission on May 1, extending the controls already in place to deal with the risk of terrorism, to which the risk of a pandemic was added from the beginning of March.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :