Democracy and citizenship

Eric Maurice,

Magali Menneteau

-

Available versions :

EN

Eric Maurice

Magali Menneteau

The new Strategic Agenda, negotiated by Member States, the Council and the outgoing Commission, will act as a basis for the work agenda of the next Commission. This year it may be supplemented by a platform presented by the 4 main political groups in the European Parliament united in coalition - the European People's Party (EPP), the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), Renew Europe (RE) and the Greens/EFA.

As such it constitutes a five-yearly state of play and an indication of the way in which its leaders see the situation. We therefore thought it interesting to compare the Agenda adopted on 20th June with its predecessor[2], adopted by the European Council held on 26th and 27th June 2014.

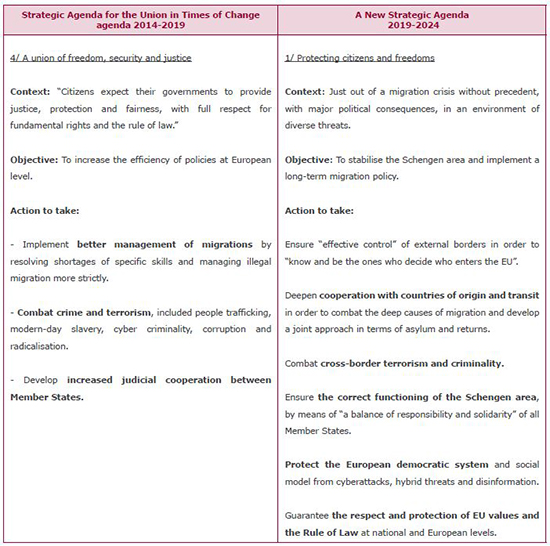

Between the two Strategic Agendas, priorities are generally similar, organised around four major themes: security and freedoms, economy and social, energy and the environment, the Union and the world.

However, in the new Agenda, priorities 2 and 4 have been grouped under the title "Protecting citizens and freedoms" and have become the top priority.

1. Security and freedoms

Both strategies underline the importance of the combat against illegal migration flows. But whereas in 2014 this combat was presented as a counterpoint to the search for skilled labour from outside the EU, in 2019 the European Union considers that the protection of its borders is a "absolute prerequisite" for the security of Europeans and for "ensuring properly functioning of EU policies".

The change in tone and the insistence on control of access to Union territory, the asylum and returns policy and the balance between solidarity and responsibility (already mentioned in 2014 but much more insistently in 2019) constitute the European leaders' response to the acute migration crisis that the Union experienced in 2015-2016 and the increase in populism and nationalism, which is partially the consequence thereof.

The Agenda adopted insists on Member States' "determination" to draw up a "fully functional and comprehensive" migration policy and to find a consensus on the reform of asylum policy, about which discussions have been blocked at the Council since 2016[3] But it does not give any new directions by which to achieve this objective.

The question of the rule of law, absent in 2014, has now been stated, whereas a sanction procedure was brought against Poland in 2016, whereas the European Parliament voted in 2018 for the opening of a procedure against Hungary and whereas concern has been raised in countries such as Romania and the Czech Republic. The language remains vague, however, in order to guarantee its adoption by the heads of State and Government, including those targeted.

In the 2014-2019 Agenda, cybercriminality was mentioned only once and disinformation got no mention. After interference in European elections over these past few years, by means of computer attacks or false information in the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain, hostile activities on line are now considered to be an increasing threat against the European political and social model. Between January and May 2019, the Commission recorded over 1,000 cases of disinformation in the Union, compared with 434 over the same period in 2018. At the same time it observed "continuous and sustained disinformation activity by Russian sources"[4].

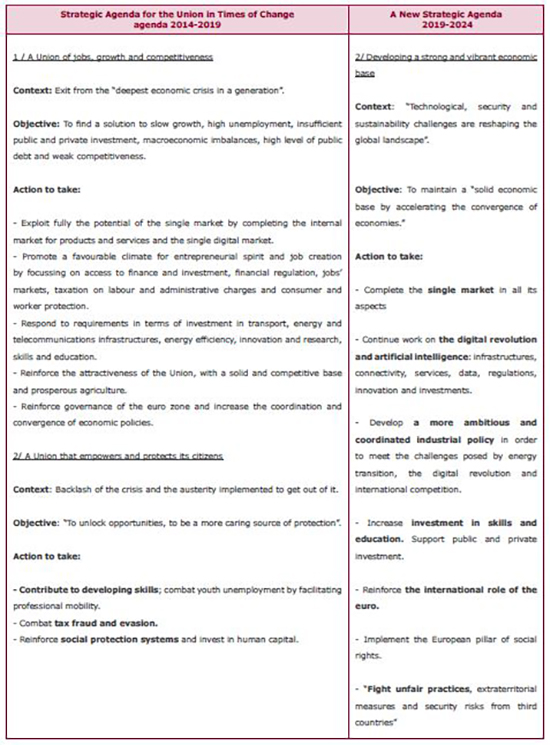

2. Economy and social

Over the past five years the Union's economic and social situation has changed a great deal, and this is reflected in the differences between the two strategies. In 2014 growth had only been seen for less than a year following the recessions of 2009 and 2012-2013, and currently remains uninterrupted. The unemployment rate was at 10% compared to 6.4% in the spring of 2019 and youth unemployment was at 21.7% compared with the current figure of 14%. It was time for a kind of rebuilding of the European economy and its human capital. Henceforth the Union must maintain its capacities in order to hold its place in world competition, whilst anticipating the next crisis. The focus is therefore on structures of the European economy with a strong international dimension, as demonstrated by the will to strengthen the euro's world role.

Economic and social convergence between Member States is underlined, no longer as a means by which to get lastingly out of the crisis, but as an instrument to ensure Europe's role on the world stage.

The importance of the single market is underlined in both agendas, with particular insistence on services in 2019. This meets a strong demand from certain Member States, notably expressed in a joint letter signed by 17 States at the beginning of 2019, as well as the growing integration of services in value production.

To adapt to the "digital transformation", the Agenda calls for the development of the services economy and the integration of digital services to accompany action on infrastructure, connectivity and data and regulation of the sector. Because in addition to the economic aspect of digital, the 2019 Agenda includes a sovereignty aspect, underlining the importance for the Union of benefiting from the digital revolution "in a way in which it ensures the embodiment of our social values, promotes inclusiveness and remains compatible with our way of life". This is one of the implicit references to the United States' progress in new technologies and China's increasing impact[5].

The social aspect is much less present in 2019 than it was in 2014. Ceasing to be a clearly identified priority, it is now inserted in a fragmented way into the other priorities, with no details on the action that can be taken at national level.

The 2014-2019 strategic agenda presented economic fields of action in a partitioned way. The 2019 agenda insists on the contrary on the need to develop a "more integrated approach, connecting all relevant policies and dimensions" such as the single market, the industrial strategy, climate objectives, artificial intelligence or taxation.

In the economic objectives it presents, the European Union moves therefore from a policy of resilience to a policy of affirmation of its status as the world's leading economic power and of its interests. It points out that this "means ensuring fair competition within the Union and on the global stage, promoting market access, fighting unfair practices, extraterritorial measures and risks from third countries, and securing our strategic supply chains."

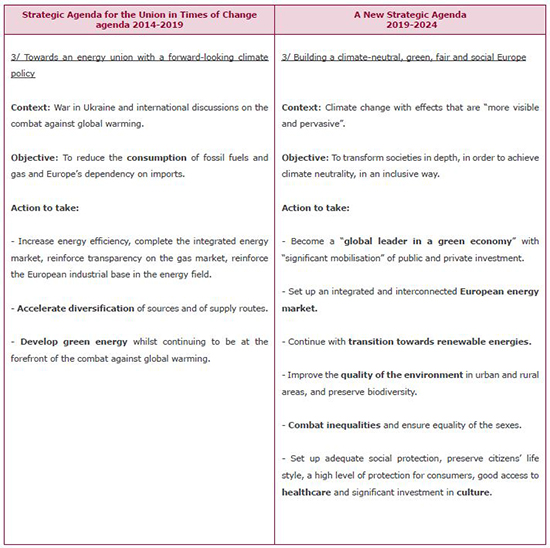

3. Energy and the environment

The energy, climate and environmental policy is the subject on which the Union evolved most between 2014 and 2019. In 2014, the year of the war in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia, priority was given to the reduction of energy dependency in Europe. The combat against global warming involved, above all, a reduction of the consumption of fossil fuels in order to facilitate transition to increased usage of renewable energies.

At the time the objectives adopted in October 2014 were to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% compared to 1990 levels, to bring the share of renewable energies up to at least 27% and to improve energy efficiency by at least 27%. The objective is now "in-depth transformation of its own economy and society to achieve climate neutrality".

Within five years, the increasing warnings from scientists, the signature of the Paris Agreement on climate in 2015, and the rise in votes for ecology parties in certain national elections and in the European elections in May 2019, had profoundly modified the approach of European leaders. Due to opposition from several Member States (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia), European leaders have decided against setting the date at 2050 to achieve climate-neutrality.

The 2019 Agenda mentions only once the reduction of "dependence on outside sources" It refers to climate change as an "existential threat" against which the Union must intensify its action "urgently".

For the first time, European leaders are linking the climate issue to social policies. The Agenda notes that energy transition "will entail short-term costs and challenges" and that it is "important to accompany change" to reduce inequalities, particularly for young people and women.

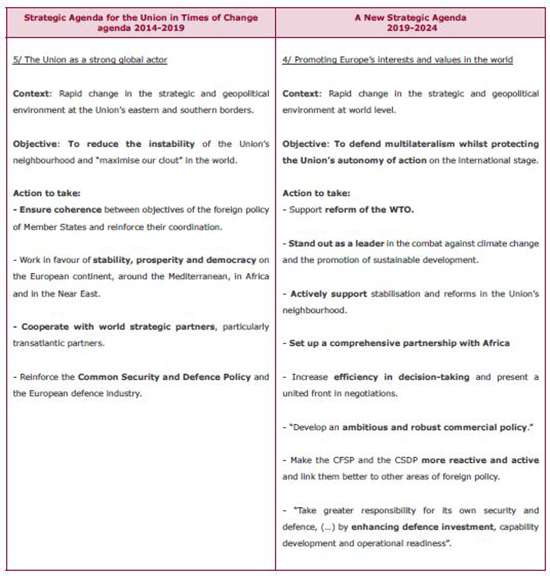

4. The Union and the world

From the war in Ukraine to the migration challenge, regional crises to challenging of the world order, the Union's external interests were massively transformed between 2014 and 2019. Its priorities now take it less towards its neighbourhood, particularly in the east, and more towards Africa, which is now considered to be a long-term partner, and world governance through multilateralism. Europe's will to affirm its position on the international stage, considerable in the economic field, is also seen in the diplomatic field as a necessity by which to guarantee the Union's sovereignty and its model of society.

In 2014 the European Union focussed on cooperation "with our strategic world partners, particularly our transatlantic partners". In 2019, confronted by an American president who sees it as an "enemy" it is turning towards "global partners sharing our values" whilst insisting on its decision-making autonomy.

Prior to this switch, the Union wanted to exercise its influence on a "wide range" of definite issues, from trade and cybersecurity to Human Rights and the prevention of conflict, not forgetting non-proliferation and crisis management. Now it wants to concentrate its influence on principles: the international order based on rules, global peace and stability, the promotion of democracy and Human rights.

By wanting to erect its "unique model of cooperation as inspiration for others", the Union affirms its "soft power" in world competition, imposing new models for world organisation whilst attempting to develop a "robust, ambitious and balanced" trade policy.

In spite of notable advances[6] over the past five years, such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund currently under discussion, this ambition to influence the world is not clearly supported by an expression of European "hard power".

The expression "strategic autonomy" is absent from the 2019 Agenda 2019, and is merely suggested by the need to "take greater responsibility" and by a reference to "the Union's decision-making autonomy" with regard to NATO. The Agenda calls for "enhanced defence investment, capability development and operational readiness", but does not go as far as stating the desire for military intervention to defend the EU's interests.

The plan to set up "a comprehensive partnership" with Africa responds to the Union's imperative need to reduce migration pressure, particularly migrants from sub-Saharan countries, pushed towards Europe by war, poverty and also, in the future, by global warming. To do so the European Union has begun redirecting its traditional development policy towards a policy of "shared responsibilities", particularly in terms of management of the transit and return of migrants. Alongside this, in 2017 it launched an external investment plan, to generate between 500 million and 1 billion euros in investments, as well as a European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD) of €1.5 billion, both of which intended for Africa as a priority. In his 2018 State of the Union speech Jean-Claude Juncker launched the idea of an "Africa-Europe Alliance for sustainable jobs and investments". This will to play a more active part in the development of Africa can be explained by the increasing presence of China on the continent, to the detriment of European influence and interests.

Moving from ambitions to achievements

The result of political compromise and balances between European interests and national sensitivities, the new 2019-2024 Strategic Agenda has been built up from discussions between Heads of State and Government since 2016 - from the Bratislava "roadmap" to the "Sibiu declaration" last May - to relaunch the Union after the British referendum in 2016.

Although uncertainty still weighs on the date and terms of the UK's withdrawal and on its future relations with the Union, Brexit is actually glaringly absent from the Agenda.

Comparison between the two strategic Agendas shows just to what extent Europe and the world have changed over the past 5 years. In 2014 the priority of European leaders was to heal the wounds of the crisis and to protect itself from hostile action by Russia. In 2019 their strategy is mainly based around the notion of "Europe that protects" its citizens, its territory and its interests, whilst attempting to build up strength for the future.

The latter also reflects the desire for unity amongst the 27 (or 28), damaged by Brexit, by economic and migration crises and by attacks against the rule of law. But a consensus has been reached on the text, at the price of flagrant weaknesses. The Agenda is thus very vague on the issue of migration, and it can be anticipated that the stated principle of strict control of borders coupled with a renewed and balanced asylum policy will not be immediately followed by any kind of decisive action. Similarly, attention paid to industrial policy and innovation, welcome with regard to technological developments, unfair competition from China and American trade threats, is not supported by precise references to action to ensure European interests. For example, there is no mention of the reform of competition law or the principle of European preference for certain public contracts, whilst Member States remain divided over the question of Chinese investments in Europe or the degree of State intervention in the industrial sector.

The social aspect of the strategy has been considerably reduced compared to 2014, due notably to the lack of any competence by the Union in this area, although the challenge of convergence between Member States is mentioned. The Agenda states that "adequate social protection, inclusive labour markets and the promotion of cohesion will help Europe preserve its way of life", but the need to combat social dumping within the single markets has been removed from the text's final version. This reflects divisions between Member States, since some of them make low salaries and poor social protection a factor of competitiveness.

The international environment occupies a major place in development of the strategy, but the Europeans' relationship with defence and the projected European force remains ambivalent.

The Agenda makes no mention of "operations beyond the EU border" as was the case in previous versions of the text during preparation, which does not guarantee that the European Union will be ready to defend its interests in other regions of the world and on the seas.

Also, fiscal competition between Member States, a sources of imbalances and loss of income, is absent from the Agenda. Whilst the text refers to the Commission's proposal to move to qualified majority in the Council on certain issues of foreign policy, Member States "forget" the same proposal in terms of taxation, which would enable the Union to overcome blockages caused by the principle of unanimity in this field.

As with any political project, the Strategic Agenda can be judged only in the light of its results and of the means implemented to achieve them. In this respect, discussions on the forthcoming Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which should be completed in the autumn, will be an indication of the will of European leaders to carry out the task assigned to them.

To improve the Union's efficiency in decision-making and particularly in the implementation of decisions taken, the Commission's work agenda should complete the Strategic Agenda with a reflection on the governance of institutions.

The presidents of the European Commission and Council could commit jointly, at the start of their mandate, to definite objectives and a working method in order to commit States to the agenda they have adopted. The Commission could also look at delegation possibilities, as provided for in the Treaty on European Union. When the commissioners' college is formed, the Commission president should also optimise the number of members. The "cluster" organisation set up by Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014, with vice-presidents in charge of horizontal portfolios, has proved its worth and should be retained.

Since Member States do not appear to be disposed to accepting the reduction in the number of commissioners provided for in the Lisbon Treaty, certain positions could be dedicated to projects rather than to a given area such as, for example, the development of artificial intelligence to ensure the Union's digital sovereignty, the development of clean and competitive mobility, the establishment of a long-term development policy with Africa, or the creation of a European cybersecurity infrastructure.

***

The Union's efficiency involves its ability to "make known". As underlined by the Commission in its contribution to the Strategic Agenda, communication is a responsibility shared between the institutions and Member States, who all too often play their own game. "It is time to get beyond the tendency to nationalise successes and europeanise failures and rather to explain our joint decisions and policies[7]." But since it is the most visible European institution, and to paraphrase its slogan on the Union's statutory activity, the Commission could "communicate less to communicate better". To target its messages better without being afraid of angering Member States, as in the case of Brexit, it should communicate only when it has a clear new message to transmit, and solely within its areas of competence. It should also do so in the name of the Union and not that of the Commission and its services, and do it directly by the commissioners, without a spokesman.

Since the European elections, European leaders and the leaders of the political parties in Parliament have insisted on the fact that the agenda for the next five years is more important that the people to be appointed to the head of the institutions.

The personality of the leaders chosen will nevertheless be a deciding factor in embodying the Union and giving a boost to implementing the agenda adopted and in responding to unforeseen events. After Jean-Claude Juncker's "Commission of the last chance", which has been able to find the resources by which to overcome poly-crises[8], the challenge now is to remain relevant in the world and to continue to have an impact.

For the new European leaders, it will be a case of making the Strategic Agenda a political project with which Europeans can identify. A Europe that projects and projects itself, not merely a Europe that protects.

[1] A new Strategic Programme 2019-2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39916/a-new-strategic-agenda-2019-2024-fr.pdf

[2] Strategic programme for the Union in an era of change 2014-2019, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/fr/ec/143492.pdf

[3] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-497-fr.pdf

[4] Report on progress on the Action Plan against Disinformation, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/factsheet_disinfo_elex_140619_final.pdf

[5] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-515-fr.pdf

[6] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-474-fr.pdf

[7] Commission's contribution to the EU's next strategic agenda for 2019-2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/news/commissions-contribution-eus-next-strategic-agenda-2019-2024-2019-apr-30_fr

[8] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-520-fr.pdf

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :