European social model

Jean-Pierre Garson

-

Available versions :

EN

Jean-Pierre Garson

Beyond these differences the Summit opened in a geopolitical context marked by uncertainty and tension within the League ( consequences of "Arab Springs", crisis in Syria and displaced persons inside or outside the country, conflicts in Yemen and political rivalries in Libya). The increase in the number of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, mainly in "transit", via North Africa is a source of concern and sometimes leads to conflicts with the local populations. There are also divisions among EU Member States countries regarding issues of international migration. Hence, some Member States (Austria, Italy, Hungary etc.) recently said they no longer wanted to take part in the distribution procedures set up by the European Commission of migrants rescued at sea or who are in a situation of distress. These uncertainties and divisions could have a serious impact on discussions, as well as on the remarks and possible recommendations that would appear in the final press release of this first meeting.

Challenges associated with international migration justify the venue of this meeting because EU Member States, just like those in the Arab League count many immigrants amongst their residents, as well as having a share of their own citizens living abroad. Over the years, migration waves and migrants' mobility have established strong economic and social links between countries of origin and destination.

1. The European Union and the Arab League: decision-making power in international migration and the magnitude of migration movements.

Due to its economic and political integration the European Union, which comprises 28 Member States (513 million inhabitants), has institutions and representatives with a disproportionate decision-making power of negotiation in comparison with that of the Arab League (22 States, 424 million inhabitants). Indeed, the Arab League is an international, but regional organisation, whose main aim is to defend "the unity of the Arab nation" and the "independence of its Member States". It does not have the power to take political decisions, resulting from the economic integration of its members, as is the case with the European Union. Nor do any of the countries share a common currency, as do the 19 euro zone countries. The Arab League does however have political and economic bodies, specialised permanent committees, which, over time have helped it strengthen its influence as well as its capacities for economic and political analysis amongst its members, including in terms of international migration.

In the European Union there are now areas of competence regarding the status of immigrants, of their families and their children, as well as the processing of asylum applications and the granting of refugee status. Moreover, between the Member States of the European Union there are commitments linking them in all matters concerning EU citizens. The European Commission is there to ensure that these commitments are implemented. However, the issue of international migration, and notably the management of migration flows from Third countries is still largely an exclusive area for national sovereignty, rather than the restricted sphere in which the European Commission enjoys priority action (principle of subsidiarity). The predominance of bilateral relations of each Member States with third countries bears witness to this, for example in terms of the granting of visas, international migration for employment or for family reunification, notwithstanding naturalisation, the recognition of immigrants' diplomas or their professional experience. The control of the European area's external borders, notably regarding the countries which signed the Schengen agreements, are also the focus of shared competence between the European Union and each of its Member States. As for the Arab League, each member remains master of its migration policy and the control of its borders.

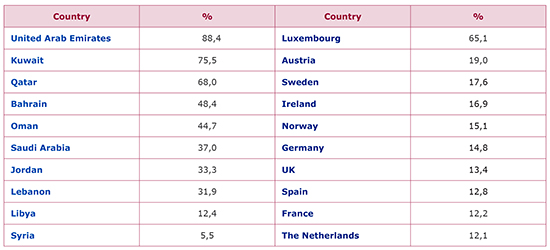

In the EU and the Arab League there are some major immigration countries, and in the case of the latter, major countries of emigration. In 2017, according to statistics released by the UN's department for Economic and Social Affairs[1], the percentage of immigrants (refugees included) in proportion to the total population[2] reached high levels in the United Arab Emirates (more than 88%), followed by Kuwait (75.5%) and Qatar (68%). In the European Union the percentage is not as high: 46% in Luxembourg, 17% in Austria and in Sweden, more than 12% in Germany, Spain and France. In terms of emigration Syria was the Arab League country with the highest level in 2017 (around 20%), followed by Lebanon (13%) and Morocco (11%). Moreover, the majority of Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian international migrants live in the EU Member States, notably in France. There are also many Moroccans living in Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and in Italy[3]. Egyptian international migrants (more than 6 million) live mainly in Arab countries, the same applies to Palestinian refugees and Jordanian citizens (UN 2018). A major share of Syrian emigrants lives in Jordan and Lebanon, another in Turkey, then to a lesser extent in Europe, mainly in Sweden and Germany.

In the Gulf countries international migrants represent much higher percentages of the total population than those in the EU's main countries of immigration. Having said this, in the Gulf countries migrants from the Arab countries only represent around 10% of all immigrants, against 70% who come from South and East Asia. It is vital also to stress that in Europe there is much more permanent migration, with significant family migration flows and the possibility in the mid-term of obtaining nationality for those who so wish it from the host country. In the Arab League countries, the predominant migration system is based on temporary migration, mainly for employment. The possibility for migrants to bring their family or to be granted the nationality of destination country is extremely limited.

2. What might we hope of the Sharm el-Sheikh summit?

− Some initial remarks

If this summit is to produce results, it is important to recognise that the statistical data available in the EU Member States regarding migration flows show that over the last two decades flows have increased constantly in many countries in the European area. Hence Europe is not a fortress, even if intra-European mobility has increased sharply (compared with migration from Third countries), following the accession of the new member countries who now enjoy free-circulation and establishment into the European Union area.

Another observation : the concept of "transit" migration can no longer represent a key element of migration policy of the countries where this "transit" is gradually transforming into extended duration of stay. Worse still, the situation of "transit", which is more or less fluid, has fed the trafficking of human beings of all kinds and especially led to the loss of thousands of human lives in their often, unsuccessful attempt to cross the Mediterranean in makeshift boats to join the closest shores of Europe. These human dramas which are most often blamed on the restrictive migration policy of the EU's Member States also call on the responsibilities of the countries of origin, as well as the so-called "transit" countries.

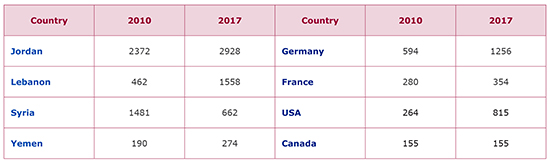

The "humanitarian crisis" (2015-2016) led to a major influx of asylum seekers and refugees into Europe, Turkey (a member of the Council of Europe, the OECD and which has observer status within the Arab League) and also into some Arab countries, notably into Jordan and Lebanon[4]. In all, in Turkey, 3.5 million Syrians have enjoyed temporary protection with the help of the European Union. The UN High Commission for Refugees has just published statistics regarding the numbers of refugees in the world - there were nearly 26 million in 2017, of which 80% are living in the least developed regions of the world[5]. In 2017, they were spread as follows: nearly 15 million in Asia, more than 6 million in Africa, 3.5 million in Europe and fewer than a million in North America. Trends in refugee flows since 2010 indicate that their increase has also been particularly marked in Africa, North America and in Asia. To these refugees we should add the displaced persons who have left their country to escape political persecution or civil war and conflict or ethnic discrimination. Annually on average, between 2013 and 2015 more than a million asylum requests were recorded in the countries of the OECD, 1.6 million in 2106 and 1.2 million in 2017. The main host countries are Germany, Turkey, France, Italy, Sweden, Greece and the UK. In 2015 and 2016, 22% on average of these requests came from migrants from Syria, 14% from Afghanistan, 10% from Iraq and 3% from Nigeria.

Beyond the most recent flows linked to the humanitarian migration crisis, we should especially bear in mind the illegal nature of most of these flows, the dangerous route taken by the migrants and the inhuman ordeals experienced by those who survived. The participants in the EU-Arab League Summit are aware of this disastrous situation, which has led many people, who want to emigrate, to leave in inhuman and financially costly conditions, whilst risking their lives at the same time. It is the entire migration path that is being questioned: the reasons for departure, the poor living conditions experienced en route, the illegal nature of the situation that the migrant experiences, both in the transit country and when he finally arrives "safe and sound" in Europe, where again, there will be other obstacles to overcome if the illegal situation continues in the country of destination. This is why, for the first time international migration has been chosen as one of the main themes of this Summit.

− Understanding the agenda of the first EU-Arab League Summit

The Summit's official agenda published one week before the meeting included no specific indication under the point "international migration"; the field was left open, not so that people would have to "guess" the content, but especially, to include it, as is the goal of this article, in a more structural perspective of migration and development issues. This approach would allow not just the consideration of the dominant spirit behind the organisation of this first meeting, but also future prospects. On the one hand, this means planning future agendas in view of opening deep, constructive dialogue regarding international migration as one of the fundamental aspects of regional economic integration, the globalisation of economies and the dynamic of populations for development.

Although useful, an agenda that is just based on a short-term vision, would look rather more like déjà-vu: restricting the candidates for emigration, so that they do not take illegal routes, as dangerous, even as deadly as they are, adding a kind of financial support by creating and co-financing a greater number of distant detention centres, helping countries of origin or countries via which migrants transit, helping them combat and punish human traffickers and/or unscrupulous smugglers. Other forms of aid, undoubtedly economic, might financially reward the "proactive" countries in the fight to counter "transit migration" and those which are determined to strengthen the control of their borders. Finally, the issue of inequalities in economic development and that of demographic imbalances between developed and developing countries would also undoubtedly feature on a short-term agenda, whilst economic development can be better gauged in the mid and long-term; and that candidates for departure, who are prepared to die to join what they consider to be the "Eldorado", cannot wait for the publication by their countries of origin of better economic rate of growth and the creation of a greater number of jobs.

− Which future agendas?

A more structural outlook for the EU-Arab League Summit meetings would gain much by not linking directly - at least at first - the issue of international migration to that of development and even less public development aid. It goes without saying that co-development, seen as a means to gain greater control over migration flows, has failed. It is important now to address the international migration issue in depth in its own right and consider that of development in its decisive aspect and not just those linked to international migration. The question of a migratory policy that encourages and facilitates regular migration and the inclusion of economic development might form the heart of future discussions.

− In support of a migratory policy that grants more rights to immigrants and facilitates regular migration

To take dialogue on migration with the EU forward the Arab League might benefit on what has been done in terms of information on international migration within the European Commission via Eurostat, or via the OECD's Continuous Reporting System on Migration (SOPEMI). The Arab League might be helped by the EU and the OECD, by inviting its Member States to introduce a system to monitor migration movements and policies with statistical and analysis tools that would be useful now that the "transit" countries have become countries of immigration. This would be a first step towards constructive exchange, not only between member countries of the Arab League but also with EU Member States and the OECD, which might be included in the monitoring of migration movements and policies in the countries of the Arab League. Monitoring might at first focus on a limited number of countries, and temporarily on migration for employment. It might also benefit from the support of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Arab Labour Organisation (ALO).

We might also promote joint thought on the legal status of immigrants, moving slowly from a precarious situation (or "transit" situation) to a status of temporary migrant, with a residence or work permit; and later for example, the possibility of family reunion and the granting of more rights to the children of immigrants. These discussions might be based on what already exists in certain Arab countries, so as to move forward in this area, with greater knowledge of what is undertaken in these countries for immigrant workers in a regular situation. The same applies to the social protection of immigrants. In the past some EU Member States have been major emigration countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland) and have actively defended the rights of their citizens living abroad. Here we have material to feed discussions in future summits after mixed committee work or in joint working party.

Another area that might prove useful is that of co-operation in the fight to counter irregular migration and against the multiple reasons that lead to a situation in which these migrants are deprived of their rights or are condemned to remain hidden for a long time, with all the risks and consequences that this entails, including in terms of security. It is an issue shared by the EU Member States and the Arab League countries. There is much to be learnt from the experiences in this area and good practice might help rid us of the failed ones[6]. Again, this means progressing slowly, for example to enable immigrant workers in a regular situation to change employer or region, but also limiting and simplifying red-tape associated with the renewal of residence and/or work permits, which often means that some migrants, who were in a legal situation drift into an illegal one. The fight to counter unscrupulous employers also forms a part of the work to combat illegal employment of foreigners.

Finally, all of these measures would support a clearly defined migration policy that aims to control migration flows, whilst facilitating regular migration.

3. Development at the heart of discussions: priority areas

Often the theme of development is addressed from the "give-give" point of view, linking for example, public development aid to the control of migration flows. This approach resembles the "connected vessels" theory, which prevails when we analyse development and migration as a purely demographic phenomenon. Greater increase in population of a developing country then looks like a "demographic bomb", which will create "migration pressure" and therefore uncontrollable flows towards developed destination countries. The same applies when in certain countries, immigration is often presented as the solution to demographic decline, which gives rise to discourse on future "migrant tsunamis". In all of these alarming devices, development might become the centre of discussion, on condition that international co-operation for economic integration is strengthened between countries in the two regions in question, to grant greater attention to healthcare, youth employment and the mobilisation of financial resources, to accelerate development and to reduce economic imbalances.

− Regional economic integration can progress within the Arab countries themselves and grow between these countries and the European Union.

There are some free-trade agreement between the EU and some Arab countries. Do they move towards a real regional economic integration? There area of education and professional training might also feature on future agendas because of major flows of international students between the two areas and via labour migration. It is also possible here to draw up reviews and lay out the prospects for the recognition of diplomas and professional experience gained abroad, access to the labour market by students in the countries where they have completed their studies. Often these issues are addressed in the "migration package", whilst they might be the object of analyses and discussions that are independent of migration flows - recent or past - in a perspective linked to labour needs for economic development between the two parties. The same applies to inter-and intra company transferees, the exchange of teachers, researchers and trainees/interns. There are many programmes to facilitate the return of qualified migrants and to mobilise the competences of diaspora for the economic development of emigration countries. All of these exchanges contribute towards economic development and to regional economic integration.

Three other areas might form the focus of enhanced co-operation between the EU and the Arab League, and beyond that, with the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. They are closely linked to economic development and are also related to international migration: healthcare, employment and migrants' remittances to their countries of origin.

− Healthcare

This area of co-operation could cover all health personnel, as well as the associated infrastructures (hospitals, clinics, family planning) and medicine costs. For example, the brain drain of qualified healthcare personnel, not only damages a country's economic development, but it also impedes the possibility of migrant and their family to return to their country of origin. Another example are the inadequate resources devoted to family planning do not help reduce high rates of infant mortality, nor do they offer the possibility of introducing a policy of chosen birth control.

− Youth employment

The demographic situation and outlook are fundamentally different between Africa for example, and Europe. In 2017 young people under the age of 15 represented more than 40% of the population of Africa and those aged over 65, 3%, in contrast respectively to 16% and 18% in Europe. By 2050 the population of Africa might have doubled, rising from 1.25 billion in 2017 to 2.57 billion, whilst that of Europe could have decreased by 1.2% dropping from 736 million in contrast to 745 million in 2017[7]. Youth employment is an extremely worrying issue, which requires international mobilisation and major financial resources, keeping in mind that income differences between the rich countries in the EU and in the Arab League on the one hand, the less developed countries, some of them Arab countries, and some from Sub-Saharan Africa on the other, are enormous. For example, the gross national revenue (GNR in $ and parity purchasing power) per capita is close to 58,000$ in the USA, 40,000$ in the EU, 124 000$ in Qatar, 55,760 $ in Saudi Arabia but only 4,290 $ in Sudan, 3,130 $ in Yemen, 1,730 $ in Ethiopia and 730$ in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These income inequalities do not mean that the poorest countries do not have wealth, but simply that this wealth is not always used to the benefit of the entire population, and notably young people. Other inequalities come to light with the human development indicator[8].

The poor outlook of employment and high income inequality feature the decision to emigrate, notably amongst the youth people.

- The mobilisation and transfer of financial resources to foster economic development

Remittances represent major financial flows and resources in hard currencies for many emigration countries[9]. Most studies show that the impact of these remittances on economic development is low, even though emigrants' money contributes in reducing poverty levels. This can be explained by inadequate or too risky investment opportunities. The lack of confidence in financial and banking institutions also impedes initiatives. Whatever the case, remittances can help economic development, but cannot substitute other measures of economic governance and the valorisation of human resources, which are much more decisive for economic development. Amongst the countries of the Arab League, it is Egypt which in absolute value, receives the highest amount of remittances (nearly 26 billion $ in 2018), followed by Lebanon and Morocco (7.8 and 7.4 billion $ respectively). In Egypt and Jordan's case these remittances represent just over 10% of the GDP. In Sub-Saharan Africa the level of remittances is clearly lower (except for Nigeria, 25.7 billion $) but in countries like Gambia, the Comoros, Lesotho, and Senegal remittances represented 20.5%, 19.3%, 14.8%, and 13.6% of the GNP respectively in 2018.

The nagging question of the sometimes extremely high cost, demanded to make the transfers is regularly brought up on the agenda in terms of international co-operation between the countries from where migrants send their savings and those to whom they are sent.

We should note that migrants are prepared to pay a high price to the transfer companies (like Western Union, MoneyGram, Ria etc ...) rather than use official, less safe and less effective channels. The European Union and the Arab League could mobilise to strengthen the reliability of the official fund transfer channels, sign agreements between the Central Banks, as well as private banks, give wider voice to good practices and win the confidence of migrants regarding national financial circuits, not only to encourage migrants to use banks, but also for investments in their countries of origin. At the same time migrants increasingly use digital tools. "Connected migrants use new transfer services offered by their mobile phones. The future agendas of the EU and the Arab League summits in terms of international migration and remittances will not be able to ignore these means of transfer being used by "migrants 2.0".

***

International co-operation in the area of international migration and economic development is part of the goal for economic globalisation that is more humane and which takes more into account of the respect of human rights. It is desirable for it to bring peace and security in a context of regional economic integration, aiming for more balanced economic development. If the first Summit between the EU and the Arab League succeeds to be part of a mid-term perspective, if it enables the establishment of precise, ambitious, realistic goals, if, finally, it advocates the strengthening of international co-operation in terms of migration and development, then more will be organised in the future.

Annexes

Table 1

The ten countries of the Arab League and the European Union with the highest percentage of international migrants in comparison with the total population (2017)

Source : UN, 2018

Source : UN, 2018

Table 2

Countries of the Arab League, EU, North America with the greatest number of refugees in 2010 and 2017 (in thousands)

Source : UNHCR, 2018

Source : UNHCR, 2018[1] The International Migration Report 2017, Department for Economic and Social Affairs, UN, 2018.

[2] See table 1

[3] International Migration Outlook, OECD, 2018.

[4] See table 2

[5] UNHCR Mid-Year Trends 2018.

[6] European Migration Network, Illegal employment of third-country nationals in the European Union, European Commission, 2017.

[7] PISON Gilles "Tous les pays du monde", Population et Sociétés, INED, numéro 547, 2017.

[8] Report on Human Development, UNPD, 2018.

[9] "Migration and Development, Brief n°30, World Bank, December 2018.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :