Budget and Taxation

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

A - Debate over the total sum of the European budget seems inevitable given the negotiation's new context

1. The UK's exit modifies the context of the MFF negotiation

1.1 The experience of previous negotiations

1.1.1 The European Council's decisive role

The Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) is the keystone to the European budget-ary structure. It expresses budgetary choices and defines how the EU supports some of the policies defined by the treaties. It is adopted according to a special legislative procedure set by article 312 TFEU[1] which takes poor account of the reality of the negotiation. As is often the case in terms of the budget, there is a practice as part of the procedures defined by the texts that is solidly based on the experience gathered over the previous 5 MFF's (see annex 1).

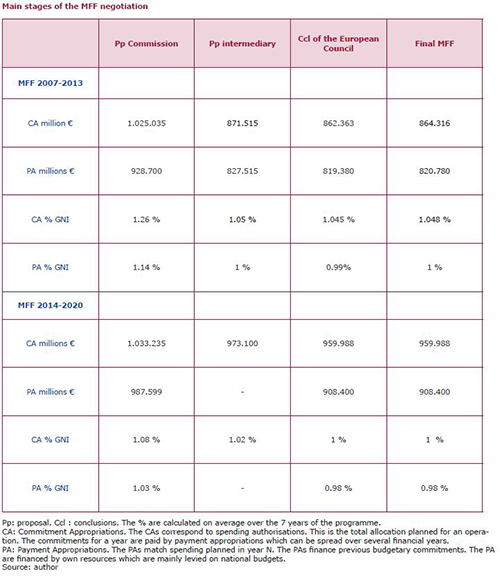

On 2nd May 2018 the Commission presented its communication on the MFF 2021-2027[2]. This was the starting point for the negotiation. However, although from a legislative point of view the Commission's power of initiative is decisive[3], from a budgetary point of view this role is much more formal. The final framework is always significantly different from the Commission's initial proposal, notably regarding the budget's final amount. In practice the MFF's figures - the total amount and the distribution of the various items - covers almost all of the conclusions made by the European Council. For the MFF 2007-2013 the European Parliament's assessment phase, before its approval, led to a marginal adjustment. Regarding the MFF 2014-2020, not one single euro was added to the sums arbitrated by the European Council.

1.1.2 The total amount of the budget, the core of the MFF negotiation

The MFF sets ceilings in millions of € in CAs per major spending categories (also called items). These ceilings are rigorous since they strictly frame the amount of appropriations that will be included in the annual budgets adopted by the budgetary authority (Parliament and Council). The amounts budgeted for are necessarily lower than the amounts included in the MFF[4].

The MFF also sets a total ceiling on the CAs and on Pas, expressed this time in percentage of the Gross National Income (GNI) based on an economic growth forecast and future GNIs.

Hence the ceilings defined must also respect the ceilings on own resources set by the Member States in a decision on own funds. Both ceilings have different functions and legal systems. The MFF ceilings are references in a way, whilst the own resources ceiling is final (annex 2).

Over the last 35 years the European budget[5] has stabilised at around 1% of the Union's GNP[6]. The ceiling has always been a bitterly debated budgetary issue during the MFF negotiation. Given the challenge of European integration, this budgetary negotiation, over thousandths of the GNI is often criticised. But 0.1% of the GNI[7] for the European budget represents additional spending of 15 billion (13.7 billion without the UK).

1.2. After Brexit the EU will lose a significant budgetary partner[8]

• The UK is an important contributor to the European budget with its participation at around 10 billion € per year (7.5 billion net contributions on average per year after the rebate and 3 billion in customs duties).

• The British withdrawal obliges adaptation on the part of the European budget. Both the total budget will decrease to take on board this loss of resources and the distribution of spending (between policies and/or between Member States) must be revised. Or the EU compensates all or part of the reduction in financing to maintain spending at its present level, i.e. it finds new own resources. These options are not mutually exclusive, and a mix is possible.

• The UK has always played a decisive political role in the budgetary negotiation. During the MFF preparations 2007-2013 and 2014-2020, it was the lynchpin in the anti-spending coalitions that formed before the start of any negotiation that was formalised in a kind of framework letter.

After Brexit the camp of those supporting a hard budgetary line will lose their central pillar. It is interesting to note that unlike with the two previous MFFs, the Commission's proposal was not "framed" by a joint letter from a group of Member States calling for a freeze on the budget.

1.3 After Brexit, Germany will lose its best budgetary ally

• Germany and the UK have often fought together in the budgetary area. Their interests were close. For a long time, they were the biggest contributors to the budget and the two leading net contributors. More than half of the movements between net contributors and net beneficiaries depended on these two countries. In other words when Poland or Greece (the leading two net beneficiaries) received 100, 50 came from Germany and the UK. At this level, nothing in the budgetary area could be done without their agreement. And so, nothing was done without their agreement.

• Major budgetary choices have mainly depended on these two countries. This was the case during the MFFs of 2007-203 and 2014-2020. They were on the same wavelength of budgetary rigour, on a different score, but both approaches were perfectly complementary. An obstinate UK, demanding severe cuts in values in the Commission's proposals, challenged European budgetary policy principles. Germany put forward ceilings that were proportionate to the GNI, thereby avoiding head-on criticism of the CAP and the Cohesion Policy, to prevent friction with its more important partners, thereby delaying the moment it had to take position until the final arbitration.

From the budgetary point of view Germany has the final word. Germany has positioned itself on 1% of the GNI. And it is 1%. Once this global figure adopted Germany has always been discreet during the rest of the negotiation. It was not concerned about the size of the items' respective shares. The main thing was that everything had to fit within the 1%. And everything did fit. Not one euro was added over the limit imposed by Germany.

For the MFF 2014-2020 the Germany-UK tandem worked perfectly. In the case of the new MFF 2012-2027 Germany will be losing its best budgetary ally. Debate between the Member States over the budget total seems to be inevitable.

2. Inevitable debate over the budget total

2.1 A ritual debate

The weakness of the community budget has been criticised for 50 years now and initiatives have been taken to increase it. However, these demands never led anywhere.

2.1.1 Recurrent initiatives to increase the budget

• Economic arguments

These arguments that are said to legitimise a budget of 2, 3 or 5% of the GNI, reflect the analysis of budgetary functions - allocation, redistribution and stabilisation, according to a known ranking[9] - that a budget reduced to 1% of the GNI is not able to shoulder. Debate dates back to the 1970's. In 1977, the MacDougal report suggested bringing the community budget up to "5% or 7% of the GNI of the EU in the first instance" with a perspective of 10%.

These arguments have gathered strength again with the introduction of the Economic and Monetary Union. There is a logic to supporting monetary unity with a budget that would enable the establishment of aid mechanism for States in difficulty without having to modify their monetary parity.

Finally, the comparison with a federal budget is clearly tempting, even if there is a gulf between the European budget[10] and a federal budget which would lead to turmoil in the distribution of budgetary competences and supposes a re-founding of the treaties.

• The political arguments

The simple comparison with national budgets undoubtedly highlights the modesty of the European budget. Public spending in the Union represented 46.3% of the GDP in 2016 of which only 1% was devoted to the budget. In 2009 and 2010 the budget, presented as being "on the front in the fight against the economic crisis,"[11] represented however, less than the budgetary deficit of France![12] At this level the European Union is singularly lacking in credibility.

An increase in the budget might also be legitimised by new requirements for solidarity (the rise in regional policies for example) and the financing of policies of common interest. Although minor changes might be financed by the redeployment of appropriations, major guidelines suppose new means.

2.1.2 Debate that disregards present institutional constraints

The feasibility of an increase in the European budget of this nature is seriously challenged by the legal framework set by the treaties. Three cases have to be clarified.

- An increase in the budget of between 1% and 1.23% of the GNI depends on the agreement of the heads of State and government alone. The MFF is adopted by the Council according to a special legislative procedure. In fact, the vital decision is taken during a European Council devoted to the conclusion of the MFF. This arbitration is practically never challenged either by the Council or the European Parliament.

- An increase in the budget beyond the 1.23% of the GNI supposes a new decision regarding own resources (ORD)[13], which implies the unanimity of the Member States and an authorisation for ratification given by the National Parliaments. This supposes a parliamentary debate therefore, an attenuated and policed form of public debate.

- A significant increase in the European budget would impose a debate over the attribution of a true budgetary and fiscal competence to the European Parliament (setting the base and level of a European tax to finance the budget for example) which it does not have right now. And which it could only have with a new treaty. Which in the present circumstances is quite improbable in the short term.

2.1.3. A debate that reduces the decisive weight of the main contributor coalitions

The conclusion of the MFF is the result of a negotiation between the Member States. National interests and the reminder of constraints, which weigh on national public finance have always won the day and imposed the strict control of the Union's spending.

This influence would become clear as soon as the negotiation started. For the MFFs of 2007-2013 and 2014-2020, the Commission's proposal was preceded by a kind of "framework letter" addressed to the President of the Commission, signed by the States' coalition. "The austerity coalition" of 6 Member States before the MFF of 2007-2014[14], "the better spending coalition", of 5 Member States[15] mocked for being the "misers' camp" before the MFF of 2014-2020. In the latter case the letter recalls that "European public spending cannot exonerate itself of the considerable work undertaken by the States to master their own public spending" and concludes in support of "a stable volume of spending"[16]. Which suggests an almost freezing of expenditure.

In other words, it was not the right time. In reality, for the States, it is never the right time. For 35 years the European budget has practically been set at around 1% of the GNI[17]. In this negotiation the influence of the main financiers has been decisive. But when 1000 billion € are at stake, how can it be otherwise?

2.2 A debate renewed for the MFF 2021-2027

It is inevitable that the level of the budget will again be the focus of new debate this year. For technical, as well as for political reasons.

2.2.1 The technical reasons: the upkeep of 1% is practically impossible

• The mechanical effect of Brexit

At present the economic weight of the UK in the EU (13.8% of the GNI) is higher than its budgetary weight (12% of the financing of the budget by the States[18]). The British withdrawal has more impact on the Union's GNI than on the budget itself. This impacts the % calculations of the GNI.

So that things are clear, a budget of around 158 billion € (CA of the 2017 budget) represents 1% of the GNI (GNI 206). A budget of 148 billion € (158 billion from which 10 billion € net contribution by the British has been subtracted) represents 1.08% of the Union's GNI. Hence even if the States do not compensate for the reduction in resources caused by Brexit, the share of the budget in the Union's GNI would increase by around 0.8%.

To maintain the budget at its present level of 1% of the GNI, the Member States would have to reduce appropriations by 21 billion € (out of a budget of 160 billion €), this reduction seems to be totally out of the question. The upkeep of the line of 1% is impossible.

• The management profile of the MFF 2014-2020

Experience shows that the implementation of the MFF is often delayed. These delays are linked to the adoption of new legal bases by the legislator and difficulties in implementing European programmes notably that are part of the cohesion policy. This leads, from the budgetary point of view, to specific spending profiles, with a weakness in commitments over the first years and a precipitation towards the end of the period[19]. The delay in commitments leads to late payments. The corresponding PAs are then financed by the following MFF.

This phenomenon was particularly clear for the MFF 2014-2020. Hence, quite logically, the payments over the period 2021-2023 will correspond with the late appropriations of 2018-2020. The budgetary peak at the start of the programming is a handicap in terms of maintaining the average PA at 1% of the GNI.

2.2.2 The political reasons

The European Union is experiencing a difficult time in its history with the withdrawal of a Member State, the rebellion on the part of others and doubts about the efficacy of European integration. Has it entered a phase of European disintegration? And yet, in this rather discouraging ambience, many continue to believe in it, and are trying to innovate to revive lost energy.

- This is the case with the Commission. The Commission, as it follows a bottom-up approach, is basing itself on requirements that are supposed to match the challenges of the moment and is assessing the amount it believes necessary to rise to these. Each MFF is marked by its economic and political environment. The MFF 2021-2027 proposal is being defined by security. "A modern budget for a Union that protects, empowers and defends" (see annex 3).

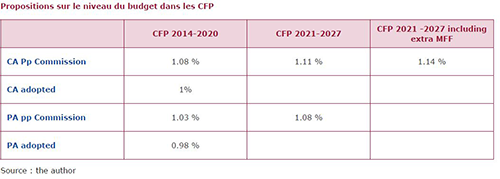

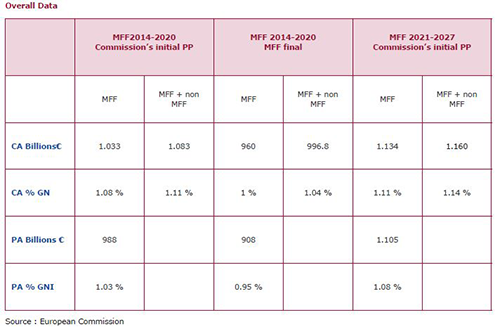

If it limits itself solely to the total amount of the budget, the Commission has an ambitious position much beyond the present level and even above its own proposal for the present MFF as it is proposing a level of 1.11% of the GNI in CAs, (and 1.14% including totals outside the MFF) and 1.08% of the GNI in PAs. The Commission is also proposing to raise the ceiling of own resources from 1.23% of the GNI to 1.29%.

- This is also the case with the French President. On several occasions Emmanuel Macron has shown that he supports a revival of European unification, calling for "a refounding of Europe"[20], pointing to the work that the European Union must do for youth, defence, security and also by formulating several budgetary and fiscal proposals (budget for the euro zone, carbon tax etc.).

The French President has committed himself too much not to be impacted by budgetary consequences. A window of opportunity to increase the budget is open. Only Germany has to be won over, remarked some commentators, as if they have foreseen that the "convergence with Germany" which the French President would like, would not happen just like that. The MFF negotiation will be the first text of this "convergence". Several reasons lead us to think that indeed, it will not be easy.

B - Probable tension between France and Germany which the two countries will manage to overcome at the cost of mutual concessions

1. Germany and France at the centre of the budgetary negotiation

No one can deny that the two countries have a dominant position in the budgetary negotiation. The political and economic weight of both countries, just like the influence of the French President and the German Chancellor in the EU are clear. From the budgetary standpoint alone, we might recall that both countries, in the wake of the British departure - will be the budget's two main financiers, even if the relative weight of each places Germany easily ahead of France. But they have different approaches and interests.

1.1 Germany's specific features

1.1.1 Germany, the budget's leading financier

Germany ensures more than 20% of the national contributions to the European budget. Its net contribution totalled 13.6 billion € on average over three years. With this net contribution Germany ensures 30% of the budgetary redistribution between net contributors and net beneficiaries.

1.1.2 Germany affected by Brexit

Although significant, Germany's net contribution is attenuated by a corrective mechanism, which means that it can reduce its participation through the financing of the British rebate. This measure, known as the "rebate on the rebate" was granted to Germany in 1985 and extended in 1999 to prevent its net contribution also from becoming "excessive", to coin a phrase from the European Council of Fontainebleau in 1984, which was behind the British adjustment. Germany only ensures 25% of its theoretical contribution (proportionate to its share in the Union's GNI)[21]. But after Brexit, the rebate will disappear, and as a result, the rebate on the rebate also! Germany will no longer benefit from the measure to alleviate its net contribution. Hence, Germany will be bearing the full weight of the budgetary consequences of Brexit - much more than the other States. Whatever the shape and size of the possible British participation in the Union's budget, Germany will witness a sharp increase in its annual contribution to the budget. Estimates range from 960 million to 2.8 billion €[22].

1.1.3 Germany affected by every increase in the budget

Every increase in the budget is financed by the States. The amount of other resources (customs duties, fines etc.) is stable whatever the amount the budget and as a result any additional spending relies on national contributions. Hence, the main share of the burden is being carried by Germany.

This detail is amplified by the predictable differential in growth between Germany and France (0.3% in 2018 )[23]. Each additional growth point by Germany leads to an increase in its share in the European GNI and as a result in the financing of the budget. If we add to this a decrease in its population, the Union's bill per capita increases yearly.

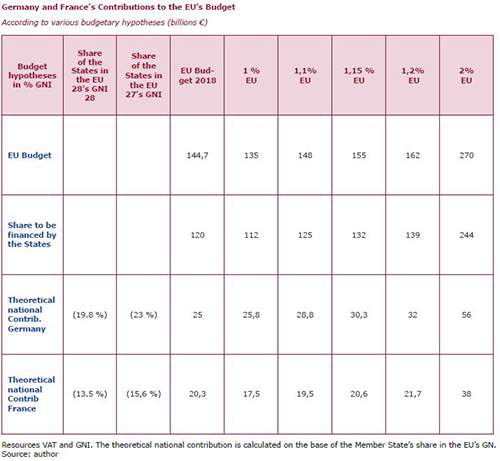

For an idea of how things stand (see annex 4):

• An increase of 0.1% in the European Budget (% of the Union's GNI) represents 13.5 billion €. Nearly 40% is financed by Germany and France.

• Every increase of 0.1% (proportionately with the GNI) in the European budget represents an additional contribution of 3 billion € for Germany and 2 billion € for France.

• With a budget of 1.15% of the GNI, the German and French contributions to the European budget are due to be about 30 and 20 billion € (gross contributions) respectively. With a budget brought up to 2% of the GNI, the German contribution would be 56 billion €, the French contribution 38 billion €.

1.1.4 Germany, extremely sensitive to budgetary issues

Germany has always been a formidable but discreet budgetary stakeholder, until reunification radically changed its approach to European issues, particularly in the budgetary area. On several occasions, the press and even the Bundesbank have expressed their concern. Germany, first presented as Europe's bursar, then its banker, was mocked for being the Union's "cash-cow". The Greek crisis accentuated the feeling that Germany always paid more than the others and for all of the others, including for the most spendthrift.

An increase in the German contribution, much might be sizeable, would be met by lively contestation. In Germany the coalition game is so complex that the final arbitration always takes a great deal of time and cannot be anticipated easily. Was the government agreement of March 2018 between the CDU-CSU and the SPD equivalent to a budgetary agreement? Of course it was, the SPD leader was delighted to have forced the end of the "obligatory austerity" in Europe, but does this budgetary flexibility also apply to the European budget? It is quite striking to note that on these issues German MEPs also stand together, as much as their French colleagues are divided. It does not seem very likely that after some political setbacks, and in spite of the calls on the part of the French President, that the German Chancellor will stand before her public opinion with an MFF that includes an additional bill for the German taxpayer.

Germany is forced to accept a budgetary increase.

The 1% is untenable, but the smaller the better.

1.2. The fundaments of the French position

1.2.1 France will be less affected from the budgetary point of view by Brexit than the other States

The rebate on the British rebate, granted to four countries, is financed by the other Member States pro rata of their share in the Union's GNI. Hence with 27% in all, France ensures the greater part of the financing of the British rebate. It is therefore in a more favourable position than Germany since its additional contribution, according to hypotheses of the future British contribution to the Union's budget varies from +1.2 billion to -200 million €, which means that the British withdrawal might even lead to budgetary savings.

1.2.2 In France, European debate is extremely poor

Arguments about the "cost of Europe" are often so partial and so clumsily presented that they have never really counted in public debate.

1.2.3 France ready to emerge from budgetary hypocrisy

Regarding budgetary issues, France has always found itself in a state of immense hypocrisy. It joined the austerity club not so much to maintain the European budget within tight boundaries, but rather more to prevent agreement on a reduction in the budget being made behind its back, to the detriment of the CAP, of which it is the leading beneficiary. Once the 1% had been adopted, it started criticising more and more, mocking British intransigence (never the Germans of course, so as not to be in conflict with its major ally), before finding that the decision was in fact perfectly in line with its interests[24].

Why this hypocrisy? Because in terms of Europe more than anywhere else, there is a division between policy and budget. A great number of stakeholders campaign for a European budget of size - the beneficiaries of the CAP, the regions for which the EU is still a major financial partner and some political leaders.

In the face of the latter there is a fortress in the shape of the Ministry of Finance and then the Budget Department, which is not as sensitive to the content of this budget as to its consequences on national public financing, because PAs are financed in the main by levies on fiscal revenues and weigh directly on the budgetary balance[25]. The lower the European budget the better it will be for French public finances. The French budgetary fundamentals remain unfavourable to an increase in the European budget.

Hence France is "trapped", not for political reasons as in Germany, but especially for budgetary reasons. The argument between the CDU/CSU and the SPD is similar the French split between the Bercy and the Elysée. Budgetary constraint remains high and permanent. France will have to concede that its budgetary situation is impeding its initiatives.

1.2.4 Political Commitment

The Ministry responsible for the Budget would align itself gladly with the German position. But the European political commitment made by the French President seems irrepressible. He is too committed to the refounding of Europe not to initiate budgetary change. He would lose a great deal of political credibility in France, as well as in Europe if he did not succeed - firstly, by imposing it in his own departments, and secondly, by persuading his partners to do the same.

2. Possible stumbling blocks and paths of conciliation

2.1 Points of disagreement

2.1.1 The level of the budget

This is the central point of the negotiation and the first risk of Franco-German tension. As in the past, the level of the budget is more important to Germany than its content. In brief keeping it at 1% of the GNI is untenable. Germany, the leading contributor cannot allow the European budget to slip through its fingers, since the Germans would not accept this.

Conversely, France is in a political dynamic, which is pushing it towards strong initiatives.

On 17th April 2018 E. Macron spoke to the European Parliament in Strasbourg and announced that he was prepared to increase the French contribution. And so, it has been announced.

Although the criticism made by the French President of the Germans' "budgetary fetichism" on 10th May last in Aachen will not change the reluctance caused by the French initiative, it did not directly concern the European budget, but the argument can be perfectly taken up on this occasion. By how much can the budget increase? The commission is proposing 1.14%. It is clearly a high delta, a starting point. A budget around 1.1% seems more plausible.

2.1.2 Adjustments of the net contributions

The other divisive issue concerns the net balances. France has said that it did not want to enter into this kind of logic and that it wanted to take advantage of Brexit to bring the budgetary adjustment systems adopted in 1984 to an end[26], thereby following the position expressed by the President of the Commission.

Of course, this type of calculation is derisory, indecent and small-minded in the face of the historic ambition of European integration. But the mistake would be to think that the British were the only ones to take position on this issue. In truth several other States have demanded and obtained adjustments to their contribution. Brexit will do away with the scape-goat, but it will not do away with the question of excessive imbalances. An imbalance is excessive if it is deemed as such by the State that puts this argument forward. And it is put forward in three situations - taking on board its relative prosperity, in comparison with comparable countries and when this becomes an issue of debate in public opinion. The question is budgetary, but its perception is political.

It seems very unlikely that Germany will accept an increase in the budget, which necessarily leads to an increase in its net contribution, without designing a system that limits the latter. Pathways to this have been opened. Whether this means modifying the structure of the budget and creating lines from which it might benefit or whether this means capping transfers (11 milliards € in net profits per year on average for Poland for example) or creating a widespread capping system.[27]

France has positioned itself quite clearly on this issue rejecting any type of adjustment system, for fear of being penalised. The negotiation would merit being more open.

2.1.3 French budgetary initiatives and the euro zone budget

The euro zone budget is another bone of contention. Both in form and content. The euro zone budget supposes a governance, a European Finance Minister. A budget of this type would be designed to provide the euro zone with an investment capacity and financing via borrowing, a path that the Germans deem unsustainable; this budget would also target priority countries, in other words, those helped by rescue plans and aid mechanisms, in which Germany already has a major share. For Germany the euro zone budget would in a way be non-repayable.

2.2 Likely concessions

2.2.1 The points of agreement

It is likely that the two countries agree to modify the Commission's proposals on at least two points.

- The first is the Commission's formal presentation. This presents a breakdown that it already put forward during the MFF 2014-2020 with an initial round of spending, corresponding to the usual MFF, and a second, non MFF, which includes additional flexibility measures and also "a European facility for peace" designed to help Europe complete missions, as part of the common security and defence policy, that will have 10 billion € over that period. Without debating in depth, it is likely that the States will not retain this non-MFF presentation, which artificially reduces the MFF's appropriations.

- The second is the raising of the ceilings on own resources. The Commission is suggesting an increase on the ceilings on own funds to 1.29% of the GNI. This is the real surprise in this proposal, since the present limit (1.23%), which has never been reached, even by a narrow margin, seems to be a red line for most Member States, starting with the leading financiers.

2.2.2 The Technical Measures

The measures involving the margins in addition to the MFF ceiling can be activated.

The margins are of two types:

The margins between the budgeted CAs and the MFF ceilings. These margins that appear in year N can be released by the budgetary authority to finance some operations (initiative for youth) beyond the ceilings of year N+1.

The margins beyond the ceilings linked to the flexibility mechanisms. The contingency margins beyond the ceilings that are linked to the flexibility mechanisms. The contingency margin is a tool designed to be used as a last resort, in readiness to face exceptional circumstances. An amount that cannot be more than 0.03% of the Union's GNI, can be put together beyond the ceilings set in the financial framework.

This margin, which is set at present at 0.03% of the GNI, might be increased to 0.05% without this representing an excessive effort for the partners. This measure has the advantage of remaining within the ceilings and of opening the way to other possibilities if need be.

2.2 3 The political and budgetary measures

Even though they have a decisive influence in the European edifice Germany and France are not the only ones to decide. The MFF agreement must be found through the consensus of the European Council, before finding unanimous agreement with the Council.

The two camps will have arguments to assert.

On the one hand there is the restrictive camp. The Netherlands would reject any massive increase to the budget. This has been a constant position since the MFF negotiations began. They would be joined by Austria and Denmark, and undoubtedly Sweden. Four countries for whom the Commission's proposal is excessive, and even unacceptable.

"Reduced Union, reduced budget" says the Danish Prime Minister. In a context of the declining popularity of European unification, we must also take on board aspects of "what is clearly acceptable to European citizens and minimise any possible costs linked to frustration over excessive expenditure or insufficient benefits" [28]. In other words, why should we give more to Europe? Are the advantages of pooling, put forward in axiom so obvious that the European budget absolutely must increase? Cooperation spending, notably in cross-border cooperation projects (Erasmus, research etc ...) can easily be justified. Undoubtedly this is less the case as far as redistribution spending (CAP and Cohesion) is concerned: what purpose would the intermediation of the Union serve if each State could organise the maximum recuperation of what it had paid in?

On the other hand, there will be Poland and its allies. At present Poland is in a privileged budgetary situation with an average budgetary balance over 10 billion € per year (on average over 5 years). It can rally others to its cause and be the spokesperson for the enlargement countries of 2004. Poland, as many States which joined in 2004, would push to keep the main budgetary items at a high level, i.e. the CAP and Cohesion Funds, of which it is one of the main beneficiaries. Moreover, in the present context, Poland and Hungary would deem any reduction of their returns as a disguised punishment. They would campaign for a high budget.

In this divided situation Germany and France might appear as the conciliators of extremes and launch a median solution. This will not be easy, notably with Poland.

The agreement will inevitably cover some waivers. This was the case in the MFF 2007-2013 - the agreement was achieved through adjustments involving financing or spending with the specific allocation of funds. In all the agreement led to 40 waivers. This procedure became known as "the gift logic", a method, which of course, is not worthy of the exercise or the issue at stake. Unanimity is won at this price. It is possible that this method will function once again.

The MFF budgetary negotiation goes hand in hand with a great amount of tension, but it always works out in the end - at the very last minute. Each country will have to make a gesture. Change is possible. Germany has a strong budgetary position and must change this for political reasons. France clearly has political ambition and must amend this for budgetary reasons. The introduction of the MFF has brought so much to the European Union's budgetary life that it cannot be any other way than this.

Annex 1

The negotiation of the multi-annual financial framework

The procedure applicable to the MFF is set by article 312 TFEU.

Article 312 TFEU "The Multi-annual Financial Framework" aims to ensure the orderly develop-ment of the Union's spending within the limit of its own resources. It is set for a period of at least five years. The Union's annual budget respects the Multi-annual Financial Framework.

The Council, deciding according to a special legislative procedure, adopts a regulation, setting the multi-annual financial framework. It decides unanimously after the approval by the Europe-an Parliament (...).

The financial framework sets the amounts of the annual ceiling on commitment appropriations per line of spending and an annual ceiling on payment appropriations. The expenditure lines that are limited in number correspond to major sectors of the Union's activities.

The MFF is adopted according to a special legislative procedure requiring the unanimity of the Council after the approval of the European Parliament by a majority of its members. This article mainly looks into the practice in force since 1988, when the first "financial perspectives", according to the expression at the time, were initiated.

• The MFF negotiation opens formally with a Commission proposal that officially launches the budgetary negotiation.

• During the two previous MFFs the Commission's proposal was preceded on the one hand by a resolution on the part of the European Parliament, on the other by a letter addressed to the President of the Commission, signed by the heads of State and government of a group of countries expressly asking the Commission to stabilise the total of the budget.

• The negotiation then starts between the Member States and lasts around 18 months. Since this is a budgetary negotiation, each State adheres to its own budgetary approach. Each State is acutely aware of its own interests. The share in the budget's financing and the importance of the net balances (the balance between the State's contribution to the EU budget and the European financing it then receives in return), form, in part, the starting point of the Member States in the negotiation. The national political context and the vigour of domestic public debate regarding this issue form the other part. All of this means 18 months of high tension.

• Concessions come in a second stage, and even towards the end. The countries which ensure the presidency of the Union can put forward proposals that are supposed to be conciliatory. Real concessions are undertaken during the political arbitration at a European Council devoted to the MFF. The European Council adopts the conclusions with figures, totals per item and total ceilings. These conclusions are adopted through consensus, i.e. via unanimity without a vote.

• Once arbitration is completed, by the European Council the procedure takes its formal course as planned in the treaty. The conclusions of the European Council are formalised in a Council position, subject to the approval of a majority European Parliament vote. It can approve or reject the Council's position, but it cannot adopt any amendments. The MFF is then adopted by the Council in a unanimous vote in the shape of a regulation[29]. The Council's Regulation is completed by an inter-institutional agreement (EP/Council/Commission) on the financial discipline, which sets out certain complementary measures for the management of the MFF[30].

The decisive stage is that of the European Council agreement.

Annex 2

The budgetary ceilings of the EU's budget

• The MFF's reference ceiling

The Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) sets the expenditure ceilings, in CAs, on a yearly basis over 7 years, according to major items. The amounts are set in values, in millions of € per item. The values are indicated in constant € on the basis of prices of the year in which the MFF's is proposed and in current € on the basis of an inflation hypothesis. The sum of the items provides a total ceiling.

The annual total of the CAs is then translated into PAs on the basis of a pace of disbursement established per expenditure item[31].

The two totals in CAs and PAs are then placed in relation to the estimated GNI during the programmed period. Although the CA totals are ceilings not to be broken, the rate expressed in % of the GNI over the programmed period is just an indication, a reference, based on a GNI growth hypothesis. The final rate is adjusted each year according to the most recent data available on the real GNI.

• The absolute ceiling of own resources.

The own resources ceiling is very different. It does not enjoy the same legal status[32] and does not have the same goal. Unlike the expenditure ceilings, which reflect the EU's budgetary choices, the own resources ceiling, directly established in % of the GNI, tallies with the contributing capacity decided by the States according to economic activity. Own resources cover the payment appropriations.

The ORD ceiling is a kind of budgetary lock set by the Member States on the EU's budget. This ceiling has not changed since 1993. Despite appearances 1.23% of the present GNI (Gross National Income) corresponds to 1.27% of the GNP (Gross National Product) set in 1992.

• The ceiling of commitment appropriations in the ORD

The total amount of own resources attributed to the Union and the MFF ceiling defines the Member States' contributions to the EU's budget. But the decision on own resources also provides a ceiling applicable to the CAs. The latter is set at 1 .29% of the EU's GNI. To date the CA ceiling was never used or discussed in public debate.

Where does the own resources ceiling set at 1.23% of the GNI come from?

The OR ceiling is a result of the major budgetary reform of the EU in 1988. To rise to the challenge of repeated budgetary crises on the occasion of the adoption of the annual budget (lack of resources, debate over the total amount of the budget), the EU established financial perspectives, the original name of the ulterior Multi-annual Financial Framework, and created a new own resource linked to the EU's GNP. This own resource is in fact a national contribution by the Member States levied on their tax revenues. This resource ensures the budget's balance. Theoretically it is unlimited since it would suffice to raise the GNI to finance any expenditure at any level. It was to avoid this risk that the States set a ceiling: the ceiling on own resources, expressed originally in % of the gross national product GNP).

This ceiling has been modified in three phases:

The first rapid increase between 1988 and 1992 (increase from 1.15% to 1.20% of the GNP), which tallies with the advent of the regional policy following the enlargement of 1986.

A second modest increase came between 1993 and 1999. It was then decided to increase the ceiling by 0.01% of the GNP per year to end with 1.27% by 1999. This rate is an arbitration between two trends. On the one hand the period was marked by determined European ambition following the launch of the European Economic and Monetary Union in the wake of the Maastricht Treaty. The Commission (Delors II Package) then put forward a ceiling of 1.37%. Parliament even put forward 1.4%. On the other hand, the States, which faced a widespread increase in public deficits wanted to have control over the EU budget. The compromise was found over 1.27% on the initiative of the British presidency[33].

A stabilisation phase since 1999 since the ceiling has not changed -despite appearances - because the ceiling was set at 1.27% of the GNP before being brought down to 1.23% of the GNI.

The transfer over from the GNP to the GNI did not make any difference. In national accounting terms the GNP and the GNI are equal, but match different approaches. The GNP is based on output and therefore added values. The GNI is based on revenues and therefore on wages. The aggregated GNP has not been used since 1993.

The reduction in rates comes from the modifications made to the evaluation of the GNI. The European system of accounts (ESA), which copies the UN's international accounting standards has been modified twice, in 1995 and 2000. In 1995 (ESA 95), the modifications notably involved the recognition of interest rates, software, literary and artistic works. In 2000 (ESA 2000), the modifications involved the processing of research spending and the transfer of property between States. In both cases the GNIs were re-evaluated. (The ESA 2010 led to a re-evaluation of the EU's GDP by 1.9%). The rates expressed in % of the GNI had to therefore be reduced to maintain a constant level. Hence, this is why the 1.27% of the GNP of 1992 matches 1.23% of the GNI but these two rates tally with an identical levy rate.

Annexe 3

Proposition de la Commission pour le CFP 2021-2027

The Commission presented its MFF proposal 2021-2027 on 2nd May 2018[34]

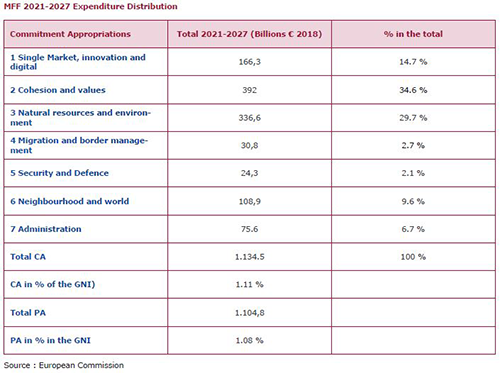

Budgetary data looks like this:

This proposal elicits the following comments.

The proposal is resolutely ambitious since the overall package over 7 years is over 1,100 billion € and the average annual level would be brought to more than 1.1% of the GNI, i.e. well over the present level and even more than in the 2010 proposal for the MFF 2014-2020.

An ambition that matches a proposal to raise the ceiling on own resources from 1.23% to 1.29%. This initiative will lead to response on the part of the Member States for whom the limit of 1.23%, which has never been reached, even closely, is in the main an ultimate, intangible limit for most.

From a formal point of view

The Commission is redefining the items. After the absurd presentation of 2014-2020 - with an item 1 - "smart, inclusive growth" and item 2 "sustainable growth" - the three main items make sense again - are more accessible and focus on 1. The single market and innovation (emphasis placed on competitiveness, the leitmotiv of the 2014-2020 programme has disappeared) 2. Cohesion and Values, and 3. Natural Resources and Environment.

This development goes hand in hand with a significant change in the distribution of spending.

Regarding the main items in the MFFs of the past, the one devoted to cohesion spending is now a leading spending line totalling 29% of the whole (330 billion € in 7 years). For the first time, spending devoted to the CAP has dropped below the 30% mark. This development had been announced and it is not as significant as expected.

Several new items have appeared. Hence for the first time the MFF mentions the EU's values and the environment. We were expecting emphasis to be put on the fight to counter climate change but the Commission notes in its proposal that this policy is transversal and is spread across all of the EU's policies. According to the Commission 20% of the budget is devoted to this.

Likewise, an item "migration and border management" has been created, to be given nearly 35 billion € in 7 years. The Commission is proposing a 'radical change for security and defence' supported by a significant budgetary item estimated at 27 billion € over 7 years.

As in its presentation of the MFF 2014-2020 the Commission is presenting the items in the MFF and others outside the MFF, notably a European facility for peace provided with 9.2 billion €

Annex 4

Possible development in contributions on the part of the France and Germany

A 0.1% increase in the EU's budget (in % of the EU's GNI) represents 13.5 billion €. Nearly 40% is financed by Germany and France.

Any increase of 0.1% (proportionate to the GNI) in the EU's budget represents an additional contribution of 3 billion € for Germany and 2 billion € for France.

With a budget at 1.15% of the GNI German and French contributions to the EU's budget would be respectively around 30 and 20 billion € (gross contributions).

With an increased budget of 2% of the GNI the German contribution would total 56 billion €, that of France 38 billion €.

[1] Article 312 TFEU.

[2] Commission Communication: a modern budget for a Union that protects, empowers and defends, 2nd May 2018, COM (2018) 321 final

[3] In the legislative procedure in the EU, as in the States, the vital stage in the drafting of a text is nearly always that of the proposal. The legislator, who adopts the text (the Parliament and the Council, in fact), often simply amend the initial proposal.

[4] With the exception of closely regulated flexibility mechanisms that enable a slight overspending in terms of the limits set by the MFF.

[5] The 2018 budget totals 160.1 billion € in CA and 144.7 billion € PAs, i.e. respectively 1.02% and 0.96% of the GNI

[6] The 1% threshold (in CP) was reached in 1984. The oscillations around 1% are related to the amount of expenditure incurred and to the rate of payments, which affect the numerator, and the evolution of GNI, the denominator. For a given amount of appropriations, the share in EU GNI decreases when the European economy is in the growth phase and increases when the economy is in recession

[7] The EU's GNI lay at 15.326 billion € in 2017.

[8] See Nicolas-Jean Brehon, "The Budgetary Consequences of Brexit" European Issue n°454, Schuman Foundation, 4th December 2017.

[9] The analysis of budgetary functions traditionally refers to the classification defined in 1959 by the economist Richard Musgrave which draws up a typology of the functions of the State, and distinguishes in any budget the functions of allocation, redistribution and stabilisation.

[10] Although procedures bring them together the EU budget, from certain points of view, is the exact opposite of a federal budget since military spending is not included (a common point in all federal budgets), likewise health, justice, police spending is very often addressed at federal level

[11] Commission, Budget Financial Report 2009

[12] In 2009 and 2010, the EU budget totalled respectively 112 and 120.5 billion €, whilst France's budgetary deficit lay at 144.8 and 136.5 billion €

[13] The adoption procedure of the ORD (Own Resource Decision) is set in article 311 of the TFEU. The ORDs are adopted by the Council according to a special legislative– unanimous - procedure after consultation with the European Parliament. This decision only enters into force after the approval of the Member States, in line with their respective constitutional rules.

[14] Germany, UK, France, Netherlands, Sweden and Austria.

[15] Germany, UK, France, Netherlands and Finland.

[16] Letter addressed on 18th December 2010 to the President of the European Commission JM Barroso signed by the French President, the German Chancellor as well as the British, Dutch and Finnish Prime Ministers.

[17] A limit in an increasingly restrictive sense. In the MFF 2007-2013, the limit of 1% involved the average amount of PAs over the period (and 1.048% in CAs). In the MFF CFP 2014-2020, this limit covered by the average amount of CAs over the period (and 0.98% in PAs).

[18] In 2016, EU GDP = 15.897 billion €, British GDP = 2.194 billion i.e. 13.8% of the EU GDP. In 2016, the EU's GDP without that of the British was 13.703 billion€. Eurostat.

[19] The threat of a clearing of appropriations, i.e. a definitive cancellation of the structural fund appropriations, is an additional incentive to spend everything that is planned.

[20] He did this during the electoral campaign. He did it during the speech of 26th September at the Sorbonne in "The Initiative for Europe". He did it on 10th May 2018 in Aachen, during the most recent award of the Charlemagne prize.

[21] European Council of Berlin 24th and 25th March 1999, conclusions of the presidency, §74 : "The financing of the UK abatement by other Member States will be modified to allow Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden to see a reduction in their financing share to 25% of the normal share." In 1985 the reduction of the German contribution to the financing of the British rebate was only 1/3.

[22] Albéric de Montgolfier, le Brexit, quelles conséquences économiques et budgétaires, p. 46, Senate n° 656 (2015-2016).

[23] Economic Forecasts Commission, 2018.

[24] Cf. development of the position of Bernard Cazeneuve JO Debates Senate 10th October 2012.

[25] It is useful to note that the document devoted to financial relations between France and the EU annexed to the draft finance bill 2018 includes a insert quite aptly on "the impact of the French contribution to the EU budget on the public deficit".

[26] It was decided that any Member State that bore an excessive budgetary burden in view of its relative prosperity might benefit from an adjustment when the right moment came. Conclusions of the European Council Fontainebleau 1984.

[27] The capping of net balances means setting a limit to the Member States net contributions expressed in a percentage of the GNI (0.4% and 0.5%). Additional net contributions are placed in a common pot which is distributed between the other Member States according to their share in the EU's GNI. For example, the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany net contributions regularly rise beyond the 0.4% of their GNI.

[28] Paper by the DG Studies at the European Parliament, working documents, budget.

[29] For the MFF 2014-2020, this is regulation n ° 1311/2013 of the Council of 2nd December 2013 setting the multi-annual financial framework for the period 2014-2020.

[30] Pour le CFP 2014-2020, il s'agit de l'Accord interinstitutionnel du 2 décembre 2013 entre le Parlement européen, le Conseil et la Commission sur la discipline budgétaire, la coopération en matière budgétaire et la bonne gestion financière.

[31] The CA and PA almost match on item 2 (sustainable growth) which tallies with agricultural spending whilst there is a large gap between the two on item 1b on cohesion expenditure. In this case payments can be spread over several years.

[32] The own resource ceiling is set by a ORD (Own Resource Decision) adopted according a special legislative procedure by article 311 of TFEU. The ORD is adopted by the Council unanimously after consultation with the EP. The ORD does not entere into force until the ME's have given their greenlight, according to their own national constitutional procedures, i.e. more often than not after the greenlight for ratification given by the national parliaments.

[33] See details of the negotiation in Philippe Jouret, Edinburgh conclusions on the Delors II Package, Common Market and EU Review N° 368 May 1993.

[34] COM (2018) 321 Final.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :