Budget and Taxation

Jean Arthuis

-

Available versions :

EN

Jean Arthuis

Singular in every way - that is how we might describe the European budget. Its financing depends on the Member States alone and the European Parliament is kept at bay, its spending lines are maintained in the straitjacket of the seven-year Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), with most of its appropriations being redistributed to its contributors. Although its weight is but modest, 1% of the European GDP, the budgetary rules and procedures seem to have been governed by an overprotective rationale via supervision and overuse of controls. Out of necessity, given the circumstances, its operators have had to distance themselves from the fundamental principles of budgetary unity, universality, annuality and sincerity. And so the budget has become a corseted, unidentifiable object to the citizen-contributor - a symptom of a Europe that no longer communicates with the Europeans.

At a time when all eyes are set on what the package of the next post-2020 MFF of the European budget might contain, we should assess the pertinence of this mechanism that locks spending expenditure authorization within a timeframe. Should its duration be reduced from seven to five years? How long can it continue to ignore the timeframe of the Parliament and the Commission's renewal?

Since these questions remain, we should firstly explore the design and the implementation framework of the present period 2014-2020. Its approval in the autumn 2013 was a test for the Parliament, which only yielded to the Council's parsimony on condition that an interim review would be made and that a high-level group comprising the representatives of three institutions (Council, Parliament, Commission) would propose financing from new own resources. It was also planned that flexibility margins would be introduced so that unscheduled events might be better apprehended. Finally, a commitment was made to settle payments arrears of over 20 billion € rapidly.

The execution of this plan soon came up against reality: the crisis of the Greek debt, sudden massive migration and the imperative of receiving refugees, terrorist attacks, cyberattacks and the need to renew investments.

Given these circumstances and the urgency of the situation the Commission tried to meet expectations and the multi-annual financial framework was effectively revised mid-term, but below the ceilings set in 2013. After long discussions between the Parliament and the Council, 6 billion € were injected into the appropriations of a 1.087 billion € package, i.e. barely 0.6%. A meagre adjustment that reflected a lack of political will.

As for the new own resources, the group chaired by Mario Monti delivered its conclusions in January 2017. The result was a lucid, rich yet critical study, firstly recommending the restructuring of the budget to make the content more legible to Europe's citizens. The guiding idea would be to order spending by missions and objectives, thereby breaking away from an abstruse presentation. As for true own resources, presently comprising customs duties only, these barely represent than 10% of the budget's total resources. Their volume is diminishing as more and more free trade treaties are ratified. These new own resources, which are difficult to establish given the diversity of national fiscal legislation and culture, have the main quality of bringing the States to break with the culture of the "fair return". Indeed, their contribution, levied on the national budgets comprise a fraction of VAT and are mainly an allocation calculated on the Gross National Income, finances 90% of EU spending.

As a result, every government ensures that it optimizes the difference between what it pays and what it receives. The two camps oppose each other. The losers block any increases to their contribution whilst the winners try to improve the net allocation which they enjoy. This is a poor show of a Europe full of national egotism. However, for the taxpayers, new own resources must not lead to an increase in their obligatory levies. In other words, any tax or levy now raised by the EU must give rise to correlative relief in terms of the contributions paid nationally. Hence it is clear that the perception of new own resources does not at all mean an increase in budgetary resources. Their main virtue is to avoid the tyranny of the "fair return", which for Finance Ministers means relinquishing the practice of a zero-sum game and finally allowing the community spirit to prevail.

Redistribution Budget and impotency in the face of crisis

Unlike the parliaments of democratic countries which are established to approve taxation, the European Parliament has no tax powers in the budgetary area. The level of financing is set by the MFF and depends on the Council, whose agreement calls for a unanimous decision. Limited to 1% of the European GDP, i.e. one 50th of the national public spending average, nearly 80% of the European Union's budget is redistributed to the Member States through two channels: on the one hand there is the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and on the other the Cohesion Funds (FEDER and ESF). The mechanism is very much like a tight corset, drawn up for the next seven years, a reflection of the recent past and unable to face any future changes. We might add that of the appropriations that are not redistributed, those that might be qualified as supranational, nearly one third ensure the functioning of the institutions (Commission, Council, Parliament, Court of Justice, Court of Auditors). The programmes managed by the Union are therefore a congruent share (Horizon 2020 for research, Erasmus, Communication Networks, external challenges, humanitarian aid and development). In addition to this, to prevent any risk of embezzlement or corruption, appropriations are only released after the completion of complicated procedures and bureaucratic calls for tender. The financial regulation that codifies them is laid out in hundreds of pages. The intervention of specialized intermediaries, paid per percentage of the subventions achieved mainly comprises costly, but vital aid. The complexity and inertia that results from this are the focus of legitimate criticism. We should however note that the national authorities have a bad habit of adding regulations, whose cumbersome nature is unjustly attributed to the Union.

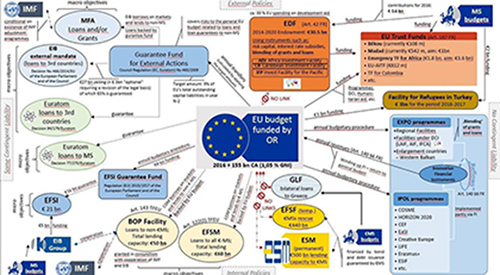

When unforeseen events occur (mass migration, refugee reception, investment renewal), because of a lack of flexibility and means the Commission is obliged to find loopholes, calling on financial engineering, creating satellites that are allocated funds, to the detriment of on-going programmes and completed with newly requested contributions from the Member States (European Strategic Investment Fund, trust funds, European sustainable investment fund). There are so many peripheral bodies that undermine the principle of budgetary unity and escape supervision by parliament. I have drawn a diagram of the European Union's "budgetary universe".

Although it is true that in the 1980's extra financing of the general budget was accepted by the Court of Justice, (aid to Bangladesh, European Development Fund) on the grounds of competence that had not been included in the treaties at the time, the regulatory texts have been revised. However, this subterfuge developed due to a lack of flexibility. The European Union's budget, which is illegible to European citizens, and also to experts, can no longer conceal the institution's political powerlessness. It is a farce and provides Eurosceptics with their arguments. With a system like this, in which the only thing that counts is the regularity of the spending, how can we show what the added value of Europe is? It is significant that some projects that are not really of any use are approved since they have been undertaken in compliance with the financial regulation.

The CAP takes up nearly 40% of the budget. It has to be said that it has not responded to the crises in which farmers have found themselves over the last few years. Its parameters have become so complicated that they can no longer be explained to the farmers. As for the Cohesion Funds that are co-managed by the Union and the Member States, they are only partially engaged. Over the last two years the gap has risen to around 10 billion €. Is this because of the difficulty felt by the operators to take ownership of nit-picking procedures or because of their incapacity to finance the unsubsidised share of the projects? In former posts I noted that appropriations allocated by the European Union, in this case the European Social Fund, can trigger public spending. Indeed, to recover a share of the subsidies that is reserved for them by the MFF, the Member States engage in new but not necessarily useful action, whose overall cost is higher than that allocated by Europe.

Lacking flexibility the budget, as it stands and implemented is coming to the end of a cycle. It clearly contravenes democratic requirements that have been mentioned so often, whereby the citizen must be able to understand the system, so that he can pinpoint problems and be able to formulate criticism, and ultimately exercise his control over it. So how might we foresee the extension of the practice introduced in 1988 of capping MFF spending, firstly over five and then seven years? The question is raised regarding the next framework: will it be five, seven or twice five years? Incidentally, should it be approved before or after the renewal of Parliament and the Commission in 2019? Can the desire for the continuity of the common policies ignore electoral stakes to this point?

Which budget for which Europe?

The budget is not just any ordinary type of legislative act. With it the entire community expresses and gauges its capacity to complete its project, to fulfil its tasks. Each projects itself into the future with perplexity and concern. The departure of the UK (Brexit) will rule out one net contributor. Due to the UK's exit, about ten billion € will be missing from the budget. In the present situation, which is so well corseted, there are a multitude of questions being raised: what programmes are threatened by clear cuts? Because of the dearth of new own resources, is it possible to imagine the Member States contributing more in compensation of the predictable net loss?

We can agree that the Union's budget must match the political and strategic vision shared by Europeans. As a result, a vital and inevitable question is raised: which competences will be the best exercised both in terms of efficacy and the economy of means at Union level rather than that of the Member States? If we support the vision expressed by Emmanuel Macron for a Europe that prepares the future and protects Europeans, what lesson are we to learn from a budgetary point of view? In terms of security and defence, growth and employment, the fight to counter terrorism, the prevention of cyberattacks and the regulation of digital activities, stemming the sources of migration, the reception of refugees? Basically, how are we to protect the public goods that the Member States cannot assume alone?

In his speech on the State of the Union on 13th September President Juncker brilliantly and convincingly developed his personal vision of the Union in 2025. His scenario, which is more ambitious than those described in the Commission's White Paper, aims to bring the volume of appropriations up to 1.2% of the European GDP. In this regard, beyond the packages, the main thing is to agree on what the Member States want to do together in view of being more effective - to launch the effectiveness of European power in the face of continents - USA, Russia, China, India, Brazil. Before setting a level of spending we must show that certain competences exercised at European level would be more effective and overall cheaper than the sum of efforts made at national level.

It is also important to recall that prior to the migratory crisis the Union suffered a colossal accumulation of unpaid bills that compressed the ceiling of appropriations available at the beginning of the MFF. The phenomenon slowed the start of new investment projects that were needed by both European citizens and businesses.

For two years now, we have faced a situation of massive under-implementation. It is possibly the sign of a complexity that is putting operators off. Although the payments crisis and the migratory crisis coincided, the Union's budget would not have been adequate anyway. Whilst the migratory, security and economic challenges are not about to go away as the end of this MFF draws to a close, a payment crisis is looming on the horizon. It has to be said that we are at the end of a budgetary cycle and method.

Right now, in the European Parliament, we are of course working towards a draft of what the next budgetary framework should look like. Our President Antonio Tajani would like the package to be doubled, i.e. 2% of the European GDP. But our work remains theoretical without the prior political agreement on the future of the Union. Let's not put the cart before the horse.

As far as we are concerned we are ruling out scenarios that shrink the Union's ambitions. "Doing more together" is deemed to be the starting point, but our privileged preference is the sixth option, which is the most proactive, as suggested by President Juncker. Again, it has to be debated by the heads of State and government.

Releasing the budget from its methodological singularity and its procedural straitjacket

Whatever the answer to the question "which budget for which Europe?" several methodological recommendations have to be drawn up so that the Union can be released from its singularity and the lack of confidence surrounding the procedures by which it is governed.

1. We should make the budget more flexible by creating new internal instruments to make it easier to cope with unexpected events, notably crises. No option should be ruled out including the creation of a Crisis Reserve to mobilise the necessary resources immediately in the event of an emergency. Flexibility instruments must be used to finance unplanned events only; new priorities require new resources. This flexibility obviously calls for the courage to reduce or cancel certain programmes whose European added value does not match the appropriations with which they are provided.

2. We should respect the principles that govern the presentation of any budget. Firstly, that of budgetary unity. The "universe" is a pragmatic response to the lack of means and the rigidity of the MFF, in defiance of democratic control. The multiplication of funds and other facilities makes the European budget even more opaque in the eyes of the citizens. This distortion has to cease and give way to a single, coherent and transparent budgetary framework. This shows the importance of the recommendation drawn up by the group chaired by Mario Monti advocating a revision of the nomenclature of the budget headings in view of regrouping appropriations according to main goals (growth and employment, security, migration, climate, energy, natural resources). Secondly, the principle of budget universality. Hence, assigned revenues that come from the reduction of certain types of expenditure represent more than 10 billion €. The result of this is an optical compression of the package. The third principle, budget annuality. Some measures override this. Finally, the principle of sincerity. Sometimes some planned costs do not appear in the draft budget. References to self-producing legal bases, for peace of mind, are still a source of surprise. This singularity is dishonourable.

3. We should re-establish a fair balance between the financial instruments and subsidies. Financial instruments absorb an increasing share of the European budget. Of course, the leverage effect is tempting when means are lacking.

4. To strengthen the community spirit we should bring the obsession with the "fair return" to an end. This is why new own resources would appease tension. They should not increase the level of financing, since they would add to the burden of the obligatory contributions levied at national level. However, they would help reduce the contribution made by the Member States and make the budget more independent from national budgets. Carbon tax on the external borders, taxation of financial transactions, taxation of the activities of the digital multinationals are all paths to be explored.

5. Noting that certain prerogatives of sovereignty can no longer be exercised at national level because of globalisation, the Member States have to agree to transfer them to the European Union. Hence, the appropriations that they devoted to them should be made available, in part at least, to the European Union's budget. The goal of efficacy would be achieved without increasing public spending.

6. Finally we must simplify our regulations. The red tape and inertia that this causes is damaging the Union's image. All of those who write the rules, including the Parliament, must be aware that respecting the rules does not guarantee either added value or results. The obsession with supervision, its duplication, the accumulation of formalities reflect a climate of mistrust and give Europe an image of being too pernickety, which creates a gulf of misunderstanding between the institutions and the Europeans.

Moreover, the euro zone, the core of the community structure, which is burdened with managing the monetary sovereignty that 19 Member States decided to share, is becoming increasingly aware of its institutional fragility. When it was created a set of rules was agreed upon, the Stability and Growth pact, which would dispense with introducing an economic, financial and fiscal government. And yet the regulation is inoperative, since none of the many breaches of its rules have been sanctioned. In other words, there is neither regulation nor government. This structural lacuna was the source of the sovereign debt crisis and undermines investor confidence. A consensus is expected to strengthen the euro zone and to provide it with a specific budget whose introduction will complicate the European Union's budgetary outlook. Hence the introduction of a two-tiered Europe is looming. The question of whether the euro zone budget should be included in the Union's budget with a special line of spending and revenues, or whether a specific budget should be made, has not yet been decided.

There is one last question: might the European elections of 2019 become a stake in the next MFF? Which budget for which Europe?

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :