Democracy and citizenship

Lukáš Macek

-

Available versions :

EN

Lukáš Macek

It was the migratory crisis in 2015 that brought the Visegrad group out of its relative anonymity, when it asserted itself as the noisiest critic - at least at government level - of the German approach in terms of the reception of refugees, and the most determined adversary of the European Commission's proposals in terms of receiving asylum seekers. Even then the role of the Visegrad group was not so clear: during the vote on the quotas of asylum seekers, Poland (still under the government of the liberals of the Civic Platform, Donald Tusk's party) finally abandoned its three partners, who consoled themselves with the support of Romania. However, the arrival in office of the ultraconservative, and extremely Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party (PiS) in Poland restored the unity of the V4 group, which has since emerged with a relatively hard discourse on this issue on the part of all four capitals. Even though, when it comes to action, again, things are not so simple. As an example: Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic totally refused to receive any asylum seekers in the end on the basis of the mechanism adopted by the Council[4] - which led the Commission to trigger an infringement procedure with the latter not targeting Slovakia since it did make an "effort" to receive some people after all. Conversely, Slovakia and Hungary attacked the Council's decision before the ECJ[5], whilst the Czech Republic and Poland did not want to join in.

We should also recall that the V4 group countries are not political monoliths. This is particularly visible in the case of Slovakia and the Czech Republic. In Slovakia Robert Fico's government adopted a hard line regarding the refugee question, whilst President Andrej Kiska has defended a much more open position.[6] The opposite situation appears in the Czech Republic: the government, whilst being against the reception of refugees and quotas, maintains a moderate, mainly pro-European discourse, which is not the case with President Miloš Zeman, and his entourage[7].

It is no less true that the Visegrad group has achieved a certain profile, whilst creating a solid reputation as a "troublemaker" in the Union. It now appears in the eyes of many as the most Eurosceptic and least constructive group of countries. And this is all the more the case since the militant, radical rejection of hosting refugees - the issue which remains partial and relatively cyclical - has gone hand in hand with a more general, structural element that places the anti-refugee stance in a more worrying perspective: a challenge to the fundamental principles of liberal democracy and the rule of law.

However, on this point the Visegrad group is not the pertinent level of analysis. On the one hand, the strong political trend towards the consolidation of the anti-system, anti-liberal, and more or less Europhobic parties, is not limited just to these four countries: in Central Europe alone we might quote the example of Austria, with the FPÖ. However, it is true that until now it has only been in the V4 countries that not just "junior" partners in government coalitions, but heads of government themselves (without them coming from the ranks of the "traditional" far right, as it has developed in the West since 1945) convey an assumed discourse challenging more or less directly the liberal[8] principles which have formed the DNA of European democracies, in the West since 1945 and since 1989 as far as the former Soviet bloc is concerned. The worst thing is that beyond the discourse, controversial decisions are being adopted that challenge these principles to a greater or lesser degree. However, at this stage although this trend is limited to the Visegrad Group, it only involves two of the four countries: firstly Hungary, with the "illiberal" excesses of Viktor Orbán since 2010, then Poland since the electoral victories of Jaroslaw Kaczynski in 2015, firstly in the presidential, then in the general elections.

The European question in the general elections that took place in the Czech Republic on 20th and 21st October 2017 is simple and serious: will Prague be the third Central European capital to break the post-1989 liberal, pro-European consensus? Will the Czech government that results from these elections join the ideological and cultural battle being waged by Viktor Orbán and now joined by the real strong man of Poland, Jaroslaw Kaczynski?

The continuation of a political reconfiguration that started in 2013

Since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia on 1st January 1993, which also marked the end of a political sequence initiated by the "Velvet Revolution", embodied by the political hegemony of the Civic Forum, the pluralist democratic movement that was the guarantor of the transition from communism to liberal democracy, Czech political life was until 2013 structured around two main parties. The Civic Democratic Party (ODS) dominated the centre-right, the Social Democratic Party (CSSD) asserted itself, as of 1996, in the centre-left. In just twenty years between 1993 to 2013 the country experienced two major political changes in power (in 1998 and 2006)[9] and mainly five different government coalitions[10] under 8 different Prime Ministers (3 from the ODS, 5 from the CSSD), not forgetting the three more or less technical governments that guaranteed relatively longer or shorter transitions[11].

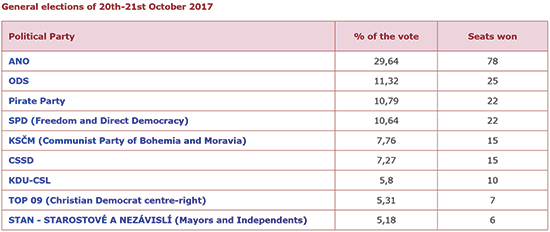

Although the small parties, the "junior" partners in the coalitions, either with the ODS or the CSSD, experienced quite a high degree of instability, with the notable exception of the Christian Democratic Party KDU-CSL[12], the two main parties seemed to have attained a longevity that was comparable to that experienced in most Western democracies, unlike the prevailing trend in the other V4 group countries. However, the 2013 elections partially brought this relative stability to an end with the unprecedented collapse of the ODS and the sudden entry of a new political force, ANO[13]. Since this movement is the main winner - with the ODS only making a timid come back and the CSSD sinking to 7.27% - it is clear that the elections of October 2017 marked the second stage of this political re-organisation that had started in 2013.

Source: www.volby.cz

Source: www.volby.cz

Beyond the collapse of the ODS in 2013 and that of the CSSD, even harsher, in 2017, this reconfiguration is also typified by a relative fragmentation of the political class, with the proliferation of "small" parties, which are managing to rise beyond the fateful 5%[14], but not over 10% threshold.

Source: www.volby.cz

Source: www.volby.cz

Another striking element in this reconfiguration: the return of the far right, absent from the House of Deputies from 1998 to 2013. During this period the only anti-system movement represented in the House, but a priori unable to join the ranks of a government coalition, was the Communist Party (KSCM), oscillating between 10 to 15% of the vote (except in 2002 when it made a breakthrough with 18.5%). In 2013 the accumulated score of the communists and the far right was over 21%, in 2017 it dropped to 18.4%. It has to be said that their margin in terms of forming a majority are narrow for the government parties, since they have refused to form misalliances with a radical anti-system party, as has been the case at national level[15], until now.

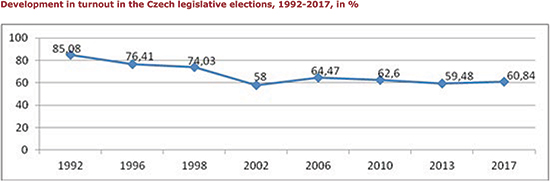

The main reason for this reconfiguration is undoubtedly the "burnout" [S1] of the political class that formed in the 1990's in the shadow of the dominant figures of this period, whose longevity has no equivalent in the other countries of Central Europe: Václav Havel (President of the - Czechoslovak then Czech Republic - from 1989 to 2003), Václav Klaus (Prime Minister from 1992 to 1997, leader of the House of Deputies from 1998 to 2002 and President of the Republic from 2003 to 2013) and Miloš Zeman (leader of the House of Deputies from 1996 to 1998, Prime Minister from 1998 to 2002, President of the Republic since 2013), with all three having been emblematic figures of the Civic Forum immediately after 1989. One of the key episodes was the unexpected rapprochement - experienced as a true betrayal by any voters - between Václav Klaus and Miloš Zeman, who in 1998 concluded the "opposition agreement": the ODS would tolerate, for the entire legislature of 1998 to 2002, a minority CSSD government. Both parties then appeared as a true political cartel built in spite of their political and ideological differences and aiming at monopolising both political and economic power. This episode, which occurred just after the first wave of scandals that notably hit the ODS, deeply shook the confidence of the citizens in the political system. From an electoral point of view this led to a sharp decrease in turnout (-16 points between the legislatives in 1998 and those in 2002,) and to the defeat of the ODS against the CSSD led by Vladimír Špidla, who clearly took a step back from the legacy of Miloš Zeman[16].

The trend towards renewal was significant in 2010, with the emergence of new political parties, sometimes traditional, recycling the number of personalities active in politics since 1989 (this was notably the case with the Christian Democratic Party TOP 09, born of a split from the KDU-CSL[17]), and sometimes - and more often - being a political "start-up" dominated by a leader-founder-financier figure: the Public Affairs Party (VV) in 2010 and more clearly the ANO movement, the revelation in 2013 and major winner of the elections in 2017. However, this relative renewal has not really succeeded in raising electoral turnout figures, which continue to show the overall "crisis" of the political system, with more than one voter in three not turning out to vote.

Source: www.volby.cz

Source: www.volby.cz

Source: www.volby.cz

Source: www.volby.cz

Many scandals have led to this "burnout" and have increased citizen disillusionment and the electoral demand for change, for novelty - as uncertain as this might prove to be. Hence, although the collapse of the ODS in 2013 was certainly due to a number of factors, some of which have been purely political or ideological, the fatal blow dealt to it was the affair that brought down its leader and Prime Minister Petr Necas. His Chief of Staff, who also turned out to be his mistress, was arrested and indicted in several affairs of corruption and abuse of power. Even though to date the legal procedures are still ongoing, without their outcome being clear, this affair brought to light a system at the top of the State that has been difficult to assume. And indeed, the effect on public opinion was all the more devastating, since this scandal, which resembled a poor farce, directly affected Petr Necas, whose reputation, until then had been that of the "Mr Clean" of the ODS, of an austere, moral conservative and a practicing Catholic.

Conversely the dramatic success of the ANO movement led by Andrej Babiš has been carried along by a discourse of a general rejection of the political class. In the Czech media-political space it has become customary to summarize his political message with the Slovak phrase "Všetci kradnú" ("they all steal"), the equivalent of "All rotten" slogan in France, although Andrej Babiš says that he has never uttered this phrase. But it remains that his political discourse is based on attacks made on the political class, denounced as being corrupt (as Babiš speaks for example of a "desperate bid by the corrupt system and traditional political leaders to do away with me"), incompetent (one of the slogans of his movement in 2013 was: "We are a gifted nation but we are governed by the inept") and lazy (another slogan in 2013: "We are not like the politicians. We work.") Finally, the name of the movement itself is eloquent; "ANO" means "yes" in Czech, but is also the acronym of the movement's original name "Action of Unhappy Citizens".

If the ODS was particularly vulnerable in 2013, four years later the CSSD was unable to find a satisfactory way to counter this discourse, even though the economic context is much more favourable to those outgoing than in 2013[18] and the CSSD has not been "crippled" by any kind of affair comparable to that which caused the downfall of the Necas government in 2013. It has to be admitted that four years in government has accelerated the erosion of the two "traditional parties" (the Social Democrats of the CSSD lost 13.2 points and 35 seats and the Christian Democrats of the KDU-CSL lost 1 point and 4 seats), whilst paradoxically ANO is emerging significantly strengthened after four years of experience in government (+ 11 points and +31 seats) and visibly still credible in its "anti" discourse, even though sociological surveys tend to show that the ANO's "anti-system" feature is losing ground in the voters' opinion, to the benefit of themes such as "competence" and "ability to implement its programme"[19].

The Babiš Phenomenon

Undeniably the subject of the election and the main issue in the sequel to events is the triumph of Andrej Babiš and his movement ANO.

The international press has multiplied its comparisons: does the probable future Czech Prime Minister resemble Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán or rather Silvio Berlusconi? Does ANO's victory justify the idea of a domino effect in Central Europe, with an anti-liberal wave, which is sweeping away the acquis of the 1989-2004 period and a double failure - at least relative and temporary - of the dynamics of democratisation, liberalisation and construction of the rule of law drawn together in a process of Europeanisation?

This much we can say right now - the "ANO phenomenon" (or rather that of "Andrej Babiš") leaves one wondering, disconcerted or worried even, but it has nothing in common with the Polish PiS or the Hungarian FIDESZ. Indeed, in both of the latter cases we are witnessing the assertion of a strong, relatively coherent ideological alternative, - which are similar in both countries, as shown by the excellent relationship shared by Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Viktor Orbán, each appointing the other as his role model, with the Hungarian Prime Minister saying that he is prepared to defend Poland, if a procedure is launched against the country by the European Commission regarding the respect of the EU's fundamental values. This ideological convergence is occurring to the backdrop of a very conservative view of European society and identity, and deep mistrust of mainstream politics, deemed to be decadent, weak and embodied by the European Union and its institutions[20]. Andrej Babiš - and ANO - seem to be far from this paradigm, even though they do share some elements, notably a certain disdain for the "weakness" of the EU and more generally of the "traditional" political elites. But this attitude seems to be rather based on an entrepreneurial vision of politics that tends to oppose efficiency and a strong ability to decide, the features of business management, against the cumbersome nature of political decision making in parliamentary democracies - and a fortiori at European level. In both cases there is the danger of a wish to weaken the system of checks and balances or even to reject European authorities. But the ideological motivation - that drives the Hungarian and Polish leaders - deepens this risk and makes it more permanent, because there is a real project to transform society - an ambition that does not seem to be part of Andrej Babiš's plan. The problem with the latter seems, on the contrary, to be rather more the inexistence of a well-established ideological framework.

Hence unlike the Polish or Hungarian cases, the participation of ANO in the government of the Czech Republic since 2013[21] has not led to tension with "Brussels", with the notable exception of the dispute over the quotas of refugees in which ANO was not any more virulent than its coalition partners. It was quite the contrary: regarding migratory and security issues the CSSD Interior Minister Milan Chovanec seemed in many ways to be real government hawk, with the dove being rather more the ANO Justice Minister, Robert Pelikan. Overall, although ANO has built its success on an anti-establishment discourse, its integration into the "system" has occurred quite easily, all the more so since its campaign in 2013 was politically anchored in the centre and opposed to the main rival at the time - the ODS - in a resolutely pro-European stance.

This orientation was clearly confirmed in 2014 during the European elections with an ANO list led by Pavel Telicka, one of the most "Europhile" figures in the country and with membership in the ALDE group in the European Parliament. It was also an Andrej Babiš's candidate, Vera Jourová, until then the ANO Local Development Minister - who was put forward by the Czech government for the post of European Commissioner. At the time Andrej Babiš himself spoke about joining the euro zone. Unlike Viktor Orbán, the discourse and the anti-system stance adopted by Andrej Babiš then seemed to be more like what happened in France with the rise of Emmanuel Macron, rather than examples of national populism witnessed in other European countries, including Central Europe: a critical discourse and an original method that breaks with customs of the established political class, but which remains set in the continuity of the fundamental values and political goals of the "mainstream" and which is trying to position itself in the centre of the political field, by relativizing the pertinence of the left/right cleavage.

However, things are not quite clear anymore. A certain number of figures who typified this centrist, pro-European position in Andrej Babiš's movement have been marginalised or have broken away from him. This is notably the case of Pavel Telicka. This is probably significant that, according to what was said in the press by the latter, he had agreed with Andrej Babiš to make information about their "divorce" after the general election. But Andrej Babiš finally published information two weeks before the election showing that he did not consider the break from the man, who embodied his European commitment, as a handicap, and that maybe he even hoped to send a Eurosceptic message to his electorate, which says a great deal about his strategic repositioning. Indeed, there might be a pragmatic, quite understandable logic to this: when it was about beating the ODS, a party reputed for its Euroscepticism, Andrej Babiš tried to convince the centrist-pro-European electorate. In this election it was about beating the CSSD, and so he donned the boots of Euroscepticism, or in all events showed his lack of enthusiasm for the European project. Since the country's mood has developed greatly since 2014, notably due to the migratory crisis, this hypothesis is far from being unrealistic. And it again highlights the deeply pragmatic and even opportunist, "a-ideological" nature[22], of ANO, as well as its "demagogic" character, since the political line seems to be dictated rather more by the polls and by political marketing than by a firm, predefined ideological line of thought.

The hypothesis of a deliberate Eurosceptic push creates doubt about what is to follow. Is this an electoral stance without a future or a change in the long term position that will be reflected in the government policy when ANO takes office? Now, other factors increase this uncertainty, starting with the ambiguous relations - as of 2013 - entertained with President Miloš Zeman, an extremely ambiguous person himself, notably regarding European issues.

A self-proclaimed European federalist, the president who introduced the European flag to the Castle of Prague (the seat of the presidency) after two mandates exercised by the extremely Europhobic Václav Klaus, Milos Zeman has unceasingly appeared to be the best European ally of both Russia and China, and also the herald of the supporters of the hard line in terms of the rejection of refugees, with an approach that has included many features typical of the language adopted by the European far right, notably the amalgam between refugees, Islam and terrorism. However, ANO is letting doubt reign over its strategy regarding the Czech presidential election of January 2018: it seems quite likely that the country's leading political force will neither put a candidate forward nor even support one of another party, which might help the re-election of Miloš Zeman. Andrej Babiš is avoiding criticism of the president, which was one of the reasons for the split with Pavel Telicka. Miloš Zeman has not missed an opportunity to laud Andrej Babiš and to help him in his conflict with the CSSD. Indeed this game is inseparable from the "cold war" between ANO and the CSSD within the government coalition and the settlement of accounts between the former and the present leader of the CSSD. This party has never recovered from the split that occurred in 2002-3 after the departure of Miloš Zeman, between his supporters and those - including outgoing Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka - who wanted to break from his legacy. Again Andrej Babiš's attitude can be interpreted as a short term tactic or a strong trend for the future. This is especially so since, although the President of the Republic only plays a weak institutional role in the Czech Republic, the period that immediately follows the general elections is an exception that confirms the rule: the president easily controls the calendar and it is totally at his discretion to appoint, twice, the person who will be responsible for putting the government together and who will become Prime Minister[23]. Hence, since 7th November 2017 is the deadline to appoint candidates for the presidential election in January 2018 it is highly likely that Miloš Zeman will take his time and take advantage of the situation to put pressure on Andrej Babiš, so that ANO's strategy in the presidential election will be as favourable to him as possible.

Beyond the alliances there has been a development in discourse regarding some important issues. Again the key words are ambiguity and uncertainty, as far as the real orientation for the next few years to come are concerned. ANO's electoral programme speaks of the EU quite briefly, but positively overall: belonging to an efficient Union is defined as the priority interest of the Czech Republic. Even the adoption of the euro has not been ruled out a priori (even though according to the most recent polls the share of Czechs who favour this decision is below 20%[24]), it is conditioned by a prior reform of the euro zone aiming to guarantee "greater economic and financial stability" to Europe. On a more general level ANO says that "we shall orient ourselves, without any ambiguity, towards a free, democratic world, and at the same time the promotion of human rights will remain a major pillar in Czech diplomatic work." In the context of Czech public debate, it is clear manner to fall in line, in terms of foreign policy, with the pro-Western consensus of the post-1989 government parties and to claim acceptance of Václav Havel's legacy, whilst making a distinction not only from the anti-system parties (KSCM, SPD) but also from the ODS's Euroscepticism and the pro-Russian and pro-Chinese tendencies of Miloš Zeman, which are conveyed even by a part of the CSSD.

Yet there is the discourse of Andrej Babiš, which is clearly less polished and coherent with the membership of his movement within the ALDE chaired by Guy Verhofstadt in the European Parliament. Just one example of this was published by Bloomberg in June 2017 when it quoted him regarding the European Union and the euro: "No euro. I don't want the euro. We don't want the euro here. Everybody knows it's bankrupt. It's about our sovereignty. I want the Czech koruna, and an independent central bank. I don't want another issue that Brussels would be meddling with.""[25] We are far from the lofty speech about the Czexit that can be heard on the far right or even sometimes within the ODS, but on the other hand the style and the substance of his words sound more like those who belong to the ECR rather than the ALDE.

There remains what is undoubtedly the biggest problem as far as Andrej Babiš and ANO are concerned: the question of his idea of public affairs and politics, as well as the enormous danger of conflicts of interest, when the country's second richest man takes on the highest government responsibilities. This is not forgetting the grey areas of his past and the circumstances surrounding the construction of his empire and the legal problems he has at present. Not only is it rare to have a Prime Minister who has been indicted in his country, but it is certain that the Czech Republic will be the first of the EU's Member States to be represented in the European Council by a man whose activities are under investigation by OLAF - according to unofficial information published by the press and freely communicated by his adversaries.

Regarding his idea of democracy and his relationship with checks and balances, one of Andrej Babiš's best known slogans on his entry into politics expressed his wish to "manage the State as one would a business." The result of this is irritation and even disdain - not only of the political classes (the theme of "politicians who know how to do nothing else but talk for nothing" was a leitmotif of his campaign in 2017[26]), but also of the parliamentary procedures and institutions, deemed to be a useless, even damaging impediment to political action[27]. Worries about this aspect are strengthened by the example of functioning of ANO, which resembles a company rather than a political party, with the overwhelming role of the President-Founder and a quite evident lack of personalities who might provide a counterweight within the movement. The departure of personalities like Pavel Telicka clearly do not make matters any easier.

Many questions are also being raised regarding his investments in the media: his holding controls two of the country's daily newspapers. And one of the triggers of the conflict which led to his departure from the government was the revelation of a recorded conversation between Babiš and a journalist of one of these dailies that could be interpreted as an example of the abuse of "his" newspapers in the attack of his political adversaries. The concentration of media and political power in his hands even gave rise to a debate in the European Parliament.[28], without this damaging his popularity amongst a good share of the Czech citizens, who are convinced that there has been an artificial political campaign orchestrated by the right wing opposition and even the illegitimate interference of a European institution in the country's domestic affairs[29].

There remains the problem of the past and the conflicts of interest. Quite recently the Slovak Constitutional Court sent the case in which Babiš faces the Institute for National Memory, the institution which manages the political police archives prior to 1989 in Slovakia, back to the square one. The issue in this dispute is to see, in the eyes of the Slovak judges, whether Babiš worked knowingly or not with the StB[30]. Whatever the answer will be, it is a mere fact that he was a member of the communist party in the 1980's and that the regime allowed him to develop a career in international trade - an extremely sensitive area, reserved for "proven" people. Although it is nearly 30 years since the fall of the communist regime and the interest of many Czech citizens in these questions is now waning, symbolically this type of profile continues to be a problem for someone who is pretending to the post of Prime Minister. In addition to this, many questions surround the way Andrej Babiš acquired his Agrofert holding in sensitive areas such as food and petrochemicals, notably regarding the source of his original capital[31]. More recently a controversy - which might have legal consequences - involved the use by Agrofert of a fiscal optimisation trick - a sensitive issue for one who, as Finance Minister, thought it absolutely necessary to bring tax evasion to an end.

"Babiš's companies received 2.6 million € in European funds but the Finance Minister is the guarantor vis-à-vis the Union regarding the correct distribution of these means. How can someone with personal financial interests as big as this be their guarantor at the same time? This conflict of interest challenges the credibility of the monitoring systems of the Czech Republic." This quotation by Ingeborg Grässle[32], MEP, Chair of the European Parliament's budgetary control committee summarises the core of the problem in terms of the conflict of interest. Andrej Babiš entered politics and government and yet remained the head of an industrial empire, a major consumer of Czech and European public subsidies. Moreover, he introduced in politics a series of people from his holding Agrofert[33], creating a mix of genres and an overlapping between the latter and the State, which goes well beyond Babiš's person alone. His coalition partners, the CSSD and the KDU-CSL closed their eyes on these problems, inviting not only ANO into government but accepting Babiš as Finance Minister. It was only after more than two years that they "discovered" the problem and with the support of the opposition - and against the veto of President Zeman - they adopted a new law against the conflict of interests - named the "lex Babiš" by journalists and by the person in question himself, who denounced the law as an unprecedented example of ad hominem persecution[34]. However, we might doubt the effectiveness of this bill: it forced Babiš to transfer his holding over to the temporary administration of a trust fund, the administrators of which are his wife and lawyer. A future European regulation that is soon to be passed may be devoted to the issue and be more restrictive than the Czech "lex Babiš" and might revive debate over the issue and open a new chapter in the complicated relations between Babiš and the EU.

Another aspect of the conflict of interest - and possibly even abuse has been highlighted by the publication of a recorded private conversation that suggests that Babiš had used the Finance Ministry's services to put pressure on a rival company to Agrofert. What weakens this accusation and its impact on public opinion however are the strange circumstances surrounding the recordings. Their origin is unknown and probably illegal, and no certainty has been established regarding the absence of manipulation (Andrej Babiš does not challenge their authenticity but maintains that they have been maliciously manipulated) and that they were published by an anonymous Twitter account, probably linked to highly suspect spheres in terms of public morality and transparency.

In the meantime the case that is more directly dangerous for Mr Babiš, for which he was indicted in September, is that of the "Capí hnízdo": a holiday resort that is said to have been financed fraudulently with European funds. This affair is dangerous because on the one hand - unlike the other cases in which he is challenged - it is relatively simple: to get an European subsidy reserved for SMEs, Andrej Babiš removed one company from his holding so that it could carry the project, concealing the fact that the owners of the company were close family. Once the project had been completed and the time span for the respect of eligibility criteria demanded by the EU had expired the company was re-integrated into Agrofert. Another problem that makes this affair more dangerous than the others: Andrej Babiš changed his story several times before admitting what he previously denied. Political careers have been broken for less than that in the Czech Republic[35], but although the affair possibly helped impede ANO's electoral dynamic (it did not rise above the 30% mark unlike the ODS and the CSSD in their heyday), it did absolutely nothing to damage the wealth of trust that Babiš enjoys, which at the same time highlights the extent of the "Babiš phenomenon."

Indeed the latter is a perfect illustration of the depth of the crisis in traditional politics in Europe, and which is particularly strong in Central and Eastern Europe due to the latter's recent, often superficial democratisation. It typifies a certain number of worrying trends: the primacy of political marketing, the oligarchisation of politics with a mix of genres between public action and business, a simplistic anti-system discourse etc. Inherently it bears with it the risk of massive, permanent conflicts of interest, which in turn might increase the mistrust of the citizens with regard to the democratic institutions. However, does it herald an authoritarian drift as far as the Czech Republic's establishment in the camp of liberal democracies is concerned, and a Eurosceptic drift in terms of its geopolitical orientation?

At this stage the answer is an open one. The concern expressed, sometimes excessively, by its adversaries are based on real facts. But the electoral base and the fundamentals of political positioning remain relatively moderate. There is a danger of radicalisation. The exercise of government office - already assumed by ANO over the last four years - often has a moderating effect, unlike the dynamic of electoral campaigns. The fundamental issues will therefore be that of alliances.

"The matches within the match"

Before addressing the issue of alliances and to complete the broad picture of these elections we should look briefly at some aspects of the latter. Indeed these elections were firstly a "match" opposing ANO against the rest of the political class. But behind this confrontation there are many more partial issues and some secondary "matches" also took place.

a) Power struggle on the left

For the first time since 1992 the Communist Party (KSCM) came out ahead of the Social Democrats (7.76% against 7.27%). However, this success for the KSCM is just a very feeble consolation in the face of what has been a terrible defeat: historically it was the lowest score ever achieved by the KSCM - a fall of nearly 50% in comparison with 2013. For both parties it was an unexpected setback - the average in the last 7 polls prior to the election forecast the CSSD with 13.7% and the KSCM with 12.5%.

b) Hegemony in the radical protest vote

Although the protest vote was the major winner in these elections (since voting for ANO can be assimilated to this at least in part), there is a share of radical voting for parties deemed to be disreputable extremes. Between the far left, until now clearly dominant, and the far right, the latter has asserted itself quite clearly (10.64% against 7.76%), certainly carried along by fashionable themes, notably following the migratory crisis and the rise in Islamist attacks in Europe. The far right has progressed significantly since 2013 (+55%), whilst the far left has collapsed (-48%). Overall, and this is rather surprising, the two extremes together are on the decline: they accumulated 18.4% of the vote against 21.8% in 2013, with the opposite balance of power between the two elements of radical opposition. But this relative decrease has occurred at the cost of a hardening in the discourse of the parties in the outgoing government coalition, notably by ANO and the CSSD.

c) Power struggle on the right

After many long years of hegemony by the ODS, 2013 was the year in which TOP 09 took the lead over the ODS with 11.99% with the latter hitting rock bottom, with a score of 7.72%. But with the retirement of Karel Schwarzenberg TOP 09 has collapsed and only just avoided elimination, whilst the ODS is happy with an almost unhoped for result: second place, of course far behind ANO, rising from 7.72% in 2013 to 11.32% in 2017. However, we must not forget that in 2013 TOP 09 was supported by the mayors of the STAN - which stood alone this year. The accumulated score of these two parties was 10.49%, a score that is comparable with that of TOP 09 in 2013 and just below that of the ODS in that year.

d) Power struggle between Eurosceptics and pro-Europeans

It is difficult to talk of these two categories, since the lines are blurred and the Eurosceptic discourse, to a backdrop of a disillusioned public opinion, seems to dominate, including within the parties that are reputed to be pro-European. This said, in terms of European affiliation, the matter can be seen in a different light. Supposing that ANO remains affiliated to the ALDE and that the Pirates join the Greens/EFA, the pro-European block EPP-S&D-ALDE-Greens/EFA rallies 64% of the vote and 138 seats against 29.7% of the vote and 62 seats for the three parties which are respectively affiliated to the ECR (ODS), GUE-NGL (KSCM) and probably ENF (SPD). This is practically the same power balance as in 2013, which was more favourable to the "pro-Europeans" than the situation prior to 2013. But again this analysis holds to the theory that Babiš's movement will maintain its commitment alongside the European liberals in spite of the breakup with Pavel Telicka, who was the craftsman of this rapprochement.

e) The surprise of the year: the Pirates

The success of the Czech Pirate Party is one of the biggest surprises in this election. This movement, finding its inspiration in the Icelandic, German and Swedish examples succeeded in winning over a rather young electorate, which no longer recognises itself in the political offer. They have succeeded in filling space that remained open after the failure of the Greens, who never recovered from their division and their participation in the Topolanek government between 2006 and 2009. The Pirates already tried to break through in the European elections in 2014 (with 4.78%), and they recorded some success during the local elections in 2014, but the fact that they succeeded not only in rising above the 5% mark but directly rose to third place says a great deal about the crisis ongoing in the Czech political system. With 22 seats they will be a rather unpredictable, but overall rather a constructive and relatively moderate element in the new House. Their leader, Ivan Bartoš, said before the elections that they did not want to join a government coalition and the rapid fall of certain small inexperienced parties which reached government office too quickly like the Greens in 2006 or the Public Affairs Party (VV) in 2010, undoubtedly has something to do with this.

f) The failed comebacks and disappointed ambitions

If these elections mark a record in terms of the number of lists running (31 in comparison to 23 in 2013), it is also because of several parties or personalities, who believed that the present context had opened up an interesting space for them. Hence, the Nestor of the Czech far right, Miroslav Sládek tried to make a comeback: he was the leader of the Republicans, a far right party, which was represented in the House of Deputies from 1992 to 1998. This comeback ended in a terrible defeat and 0.19% of the vote. Indeed apart from the SPD led by Tomio Okamura and the party of Miroslav Sládek, the Czech voters tempted by the far right also had the possibility of giving their votes, amongst others, to lists with suggestive names like "The Order of the Nation - Patriotic Union" (0.17%), "The Sensible - stop to migration and the EU's diktat" (0.72%), "Block against Islam - defence of our home" (0.1%), "Referendum on the European Union" (0.08%) and a slightly more established, ultranationalist party the Social Justice Workers' Party (DSSS, 0.2%).

At the other end of the political scale as far as the EU is concerned, another comeback from the 1990's failed: that of the Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA), the ODS's liberal partner in the government led by Václav Klaus from 1992 to 1998. This party undertook a resolutely pro-European campaign, advocating for example the rapid adoption of the euro. Only 0.15% of the electorate were convinced by them. The Greens, clearly with a more left-wing position than in the years 2006-2009, also tried to make a return, with a little more success, but well below the 5% mark (1.46%).

Two parties started the electoral campaign with high ambitions resolutely sticking to the Eurosceptic camp. On the one hand the Free Citizens party (SSO), a liberal, even libertarian movement and supporter of the "Czexit", mainly comprising former members of the ODS, who have been disappointed with the "weakness" of the latter. This party's optimism was stimulated by the success of their leader Petr Mach in the European elections of 2014 when he won a seat. However, they barely did better than the Greens (1.56%).

The Realists, a new party founded by Petr Robejšek, a Czech political expert living in Germany also had great ambitions and openly found inspiration in the German AfD. Their Eurosceptic discourse (with slogans like "For mother, a safe house" "For father a gun in his hands" and "For the children a Czech future") only convinced 0.71% of the electorate.

The question of alliances: in quest of a coalition

ANO's victory is clear even though its score is still just below the psychological barrier of 30%. But uncertainty has set in. It almost seems certain that Andrej Babiš will be appointed by President Miloš Zeman, for a long time his best ally in the Czech political arena, to form the next government. Based on this hypothesis which scenario might we foresee?

An alliance with moderate, liberal and pro-Western political forces might help complete ANO's normalisation, transforming it into a political party that will still have to state what its ideological position is. It will be up to the party members in the government coalition to ensure that A. Babiš's conflicts of interest remain under control and that the outcome of his legal problems does not contribute to the discredit of the institutions. Conversely, any alliance with the "hard" anti-system parties, potentially combined with a prevalence of personal interests on the part of Babiš over other considerations defining his political strategy, would be a dangerous development, taking the Czech Republic away from the European mainstream. Of course different for various reasons from Hungary and Poland, but the consequences might be relatively similar.

The main scenario which seem possible:

a) The present coalition goes on

The three parties (ANO, CSSD, KDU-CSL), which form the present government coalition would have a narrow majority of 103 seats out of 200. However, the reappointment of the present government coalition with a rebalancing according to the election results seems highly unlikely at this stage, given what has been said by the representatives of these parties. The serious downturn in relations between these three parties led to the expulsion of Babiš from the government; and given the collapse of the CSSD it seems highly unlikely that Andrej Babiš would want to continue his alliance with the centre-left.

b) ANO turned towards new partners

Indeed, Andrej Babiš might extend his hand to new partners, the ODS or the Pirate Party. A coalition with the ODS would lead to a majority - 103 seats. But to date this party has ruled out any possible alliance with ANO and Andrej Babiš has been highly critical of the ODS. And its electorate in 2017 has lent strongly to the left. As for the Pirates, without being as categorical as some other parties, it has also shown great reticence regarding ANO. And an ANO-Pirate coalition would only occupy 100 seats. Therefore another partner would have to be found, for example the STAN movement, a party of local mayors, formerly allied to TOP 09. And it goes without saying that the Pirates will undoubtedly be extremely careful about their possible participation in government. However, Babiš has never hidden his scepticism and even his irritation regarding the cumbersome nature and rigidity of the procedures that typify parliamentary democracies and government coalitions. We might then suppose that his priority will be to negotiate a coalition with one member or have a minority government comprising members of ANO only. But this might be difficult since the other parties are tending towards negative positions vis-à-vis Babiš and his movement, going as far as accusing him of being a threat to Czech democracy.

c) All against Babiš

It is based on this idea that an "anti-Babiš" front might be formed to prevent the victor from forming the next government, as in 1998 in Slovakia[36]. But this variation now seems unrealistic since it would require the votes of the SPD and the communists together. If we imagine that these two parties were motivated for this type of arrangement, for the others, joining forces with these parties, and pretending that ANO was a greater threat, would mean political suicide - not forgetting the political heterogeneity of a coalition like this, which would go beyond anything experienced to date. Moreover, while the dangers of undemocratic excesses were evident in Slovakia in the mid-1990's, the situation today is much more ambiguous in the Czech Republic.

d) ANO turns towards the extremes

However the question would be raised, in case Andrej Babiš would decide to look for support amongst the two "anti-system" parties which have 37 seats: the communists of the KSCM and the far right of the Freedom and Direct Democracy Party (SPD) led by Tomio Okamura. A straight coalition seems highly unlikely - Babiš has constantly repeated that he would not join forces with the SPD, calling Tomio Okamura "crazy" and saying that he was a "dangerous" man, but also that as far as the migration issue was concerned that they "might be able to agree". However, the variation of a minority government led by Andrej Babiš and tolerated by these two parties seems to be less farfetched. The question would be the price to pay for such a tacit alliance, how strong would it be and what degree of influence would the far left and far right really have over the executive.

This scenario would have the greatest impact at European level, lending credit to the hypothesis of an overall phenomenon of change in the direction in post 1989 Central and Eastern Europe. However it would remain distinct from the situation in Hungary and Poland and would be more like what happened in Italy for example (the coalitions of Forza Italia of Silvio Berlusconi including the Northern League of Umberto Bossi), in Austria (the ÖVP-FPÖ coalition at the beginning of the 2000's) or in Slovakia (the National Party in the government from 2006 to 2010 and again since 2016).

e) A technical or "presidential" government

Given this unique situation, with 9 parties represented in the House of Deputies, Miloš Zeman might be tempted to impose a solution that will serve his interests, as he did with the Rusnok government in 2012: after the collapse of the Necas government, the centre-right coalition was prepared to continue with a new Prime Minister. But President Zeman did not appoint the candidate put forward by the outgoing coalition. He preferred to appoint a "technical" government, comprising however, and in the main, people close to him, with at its head his former Finance Minister (in 2001-02), Jirí Rusnok. This government did not win the confidence of the House of Deputies but remained in office until the government that resulted after the snap election on 25th and 26th October 2013, was formed. Given the difficulties of the post-electoral negotiations, the Rusnok government only handed over power at the end of January 2014. Hence the Czech Republic was governed for 7 months by a "presidential" government that was never invested by the MPs. Will Miloš Zeman, whose mandate ends in January 2018 and who is running for re-election, be tempted by a similar scenario for the weeks or months to come?

The question of alliances at European level

At European level the first question is that of ANO's affiliation: will membership of the ALDE survive the Babiš-Telicka split? It is still too early to say. But it is relatively likely that Babiš's pragmatism will lead him to prefer affiliation to a group that includes several influential government parties rather than isolating himself in a group like ECR; which is clearly losing ground in the context of the Brexit. This said, European affiliation in itself guarantees nothing: the fact that FIDESZ has always preferred to remain in the EPP, rather than join the PiS or the ODS in the ECR group says a great deal.

More generally the new Czech government will have to decide whether it will carry on the work of its predecessors by privileging links with the EU and an overall Western orientation, reserving a congruous place for the Visegrad group. Or will it launch a break-away strategy in the quest for alternatives, whether this is with the Visegrad group or will there be a greater swing towards a third country. This choice will be both more significant and more difficult, if the European dynamic develops towards a more conscious, stronger scenario of a "two speed Europe". Indeed, given the state of public opinion[37], it will be politically difficult to defend the Czech Republic's participation in a possible "hard core" of the European Union. But assuming the fact of becoming a "second zone member" will not be easy either.

The Czech case is specific and the parallels made by the journalists are often far from reality. But if at all costs we want to account for the Babiš phenomenon by using foreign examples, the best summary would be the following: that he is a kind of "Czech Berlusconi" who entered politics in 2013 with a political method and position rather more "à la Macron" - whilst wielding a slogan of "all rotten" that smacked of far right populism, but who is totally understandable in the Czech situation at the start of the 21st century, and who since has been tempted by a kind of "Trumpism". The general elections that have just taken place mark a major stage in this development and the government that will emerge from this will define what will remain of the "Macronian" fundamentals (pro-European centrism, clear action to clean up the public area), up to which point "Trumpism" will go (opening towards extremes, radical populism, unpredictability, preference for a forced passage, disdain for the institutions and the established political culture, exacerbated souverainism) and/or whether the "Berlusconian" dimension (inextricable conflicts of interest and a political agenda dictated in part by legal affairs) will weigh more or less on all of that.

[1] This cooperation was launched during the summit that brought together the Hungarian President Jozef Antall, Czechoslovak President VáclavVáclav Havel and Polish President Lech Walesa in Visegrad, Hungary in February 1991. Symbolically it echoes a meeting between the king of Bohemia, the king of Poland and the King of Hungary in the same place in 1335.

[2] For example on one of the main points regarding the pre-membership negotiations, questions linked to the Common Agricultural Policy, stakes and interests differed radically between Poland and the Czech Republic.

[3] Let us quote here the example of belonging to what is now the Czech Republic in the Holy Roman Empire unlike other countries. Or the early influence of Protestantism and the rapid, strong secularisation of the Czech nation in comparison to strong Catholic countries like the Poles and the Slovaks. And even the strong Ottoman influence in Hungary, which is almost inexistent in the three other countries. Closer to present days we might quote the opposition between the Slavs and the Hungarians within the Habsburg Empire in the 19th century, the conflict between Czechoslovakia and Poland after the First World War and even the recurrent tension between Hungary and Slovakia.

[4] This refers to the temporary emergency relocation programme introduced by two Council decisions adopted in September 2015.

[5] Cases C-643/15 and C-647/15.

[6] Cf. for example his speech on the Republic's presidency site entitled "Attitude to refugees will define the heart and soul of Slovakia."

[7] As an example his spokesperson, Jirí Ovcácek recently compared on the social media the relationship between the EU and the Czech Republic like that between the Third Reich and the protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia.

[8] In this text the word "liberal" should be understood as political and constitutional liberalism.

[9] From centre-right to left (in an arrangement based on a tacit grand coalition: a CSSD minority government tolerated by the ODS) in 1998, from the centre-left to the centre-right in 2006.

[10] Centre-right (ODS, KDU-CSL, ODA) from 1992 to 1997 ; minority left-wing government (CSSD) tolerated by the ODS from 1998 to 2002 ; CSSD with the centrists, Christian Democrats (KDU-CSL) and the liberals of the centre-right, pro-European (US-DEU) from 2002 to 2006 ; ODS with KDU-CSL and the Greens (2007-09); ODS with the conservative Christian Democrats (TOP09) and a small undefinable populist party - Veci verejné from 2010 to 2013.

[11] Tošovský government in 1997-98, Fischer government in 2009-10 and Rusnok government in 2013-14.

[12] This party was represented in government from 1992 to 1998, from 2002 to 2009 and since 2014.

[13] Founded in 2011 by Andrej Babiš (Slovakian businessman, CEO founder of the Agrofert holding, a agro-food giants, the country's second richest man) this movement was on the heels of the CSSD in the general election of 2013 and then entered government, with Andrej Babiš becoming Finance Minister. He had to leave government in May 2017 under the pressure of Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka (CSSD).

[14] Czech electoral law provides for a proportional system in the lower house of Parliament based on regional lists (14 regions), with the requirement for the list to achieve the threshold of 5% in order to have any seats (in the case of lists supported by a party coalition this threshold is multiplied by the number of parties forming the coalition) and with the application of the d'Hondt method for the distribution of seats.

[15] At local or regional level coalitions including the KSCM have already existed.

[16] The 2002 elections led to the (extremely temporary) departure into political retirement of Václav Klaus and Miloš Zeman. Vladimír Špidla immediately opted for a coalition with the pro-European centre-right, in spite of the extreme fragility of his majority (101 seats out of 200), sending the ODS, into a real position of opposition for the first time since it was founded, in which it was truly cut off from power. This led to Václav Klaus quitting the chairmanship of his party. However the divisions within the CSSD and the inability of the government coalition to unite behind a credible candidate led to his election (after 9 rounds of voting which witnessed amongst other things the elimination of Miloš Zeman in the first round) to the Presidency of the Republic in 2003.

[17] TOP 09 mainly appearing as the right wing of the KDU-CSL which joined a new party launched by Karel Schwarzenberg, the representative of a grand Czech and Austrian aristocratic family, former Václav Havel's Chancellor (head of the Presidential administration). Elected as an independent senator with the support of the Greens, he became Foreign Minister when the Greens joined the government coalition with the ODS and the KDU-CSL (2006-09).

[18] Full employment, dynamic growth from an economic point of view. As for the migrant question unlike Hungary and Austria, the Czech Republic has barely witnessed the arrival of any refugees.

[19] Cf. the polls by MEDIAN for the Czech TV published by the latter on 22/10/2017.

[20] Cf. for example what was said by the two leaders during the economic forum in Krynica in September 2016.

[21] A strong presence, with the ANO Ministers holding the Finance, Justice, Defence, Environment, Local Development and Transport portfolio. Moreover Andrej Babiš seemed to be the strong man in this government until he was thrown out in May 2017, accumulating the post of Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister.

[22] Hence Daniel Kaiser, a journalist who stands out because of his Euroscepticism that has been constant since the beginning of the 2000's was astonished at the optical error made by the European press (which tended to present Babiš as an Orbán style Eurosceptic) in an article "Babiš is not a Eurosceptic, but a euro-opportunist. Jourová too." (i Echo24.cz, 19/10/2017)

[23] This person has to stand before the House within the 30 days following his appointment by the president to ask for a vote of confidence. If the latter is not won, the President appoints a second person (or the same person for a second time). It is only after the possible failure of this second bid to put a government together which enjoys the confidence of the deputies that the president must appoint the person who is designated by the leader of the House. If this person also fails, the way is clear for a snap election.

[24] 17% of the Czech citizens supported the adoption of the euro in April 2016 according to a CVVM poll.

[25] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-25/-we-don-t-want-the-euro-says-czech-tycoon-poised-to-be-premier

[26] One of ANO's posters carried the following slogan: "Figthting for those who are able and work hard. And no talking for nothing.

[27] It is significant that in his book-manifesto entitled "What I dream about when, by chance, I am sleeping", in which he aims at defining his vision for the Czech Republic in 2035 Andrej Babiš suggests to abolish the upper house of the parliament, the Senate, to reduce the number of deputies, or, at the local level, to concentrate decision-making power in the hands of a directly elected mayor, at the city council's expense, and to abolish regional elected bodies. It is to be noted that the Senate, even though it remains quite unpopular in the voters' eyes, played an important role within the system of checks and balances during the period of the "opposition agreement", as it blocked some constitutional reforms. Conversely, the non-existence of an upper house strongly facilitated the "illiberal" evolution in Hungary: the simple fact it won 52.73% in a general election gave Viktor Orbán's party a constitutional majority it has not hesitated to use in order to implement a deep and controversial constitutional reform. It should be also mentioned that Mr Babiš's projects have little chance to be adopted, precisely because it will be difficult to win a 3/5 majority in the Senate.

[28] Debate in parliament with the Commission on " the risks of political abuse of the Czech media" dated 1/6/2017.

[29] Cf. declaration by Andrej Babiš quoted by CTK, 30/5/17 : "(...) in the Czech Republic we fully respect the European institutions but we do not want them to intervene in our domestic affairs."

[30] Státní Bezpecnost (" State Security "), the Czech equivalent of the East German Stasi or Soviet KGB.

[31] In April 2017, Prime Minister Sobotka's advisors drew up an analysis of the circumstances surrounding the creation and rise of Agrofert and its owner. This document led to 22 questions which highlight controversial details in the entrepreneurial past of Mr. Babiš (cf. the newspaper www.denik.cz, 26/4/2017). The latter called the authors of this analysis " economically illiterate " and strongly criticised an unfair attack, deemed to be a campaign of denigration.

[32] Declaration made to the Czech press on her visit to Prague in March 2014.

[33] As an example: Jaroslav Faltýnek, a key Agrofert manager and member of its board until 2017 is the chair of ANO's parliamentary gorup and the first vice-president of the movement. Richard Brabec, a former leading manager of businesses controlled by Agrofert became Environment Minister. With regard to this David Ondrácka, director of Transparency International Czech Republic maintains that "Faltýnek and his sphere of influence systematically places his men in national and local businesses." (MF Dnes, 20 June 2017)

[34] Hence in the preamble to ANO's electoral programme, drafted as a letter from Andrej Babiš to the voters, he accused Prime Minister Sobotka of having "turned me into his personal enemy to be liquidated. For example via a very first bill in this country, which targets a real politician."

[35] Let us quote the example of Stanislav Gross, a young prime Minister who had to resign because of his inability to explain credibly the source of the funds he had used to buy an apartment.

[36] The HZDS, Vladimir Meciar's movement, the craftsman (on the Slovakian side) of the Czechoslovak separation and outgoing Prime Minister considered to be the leader with authoritarian leanings (to the point that the EU removed Slovakia from the CEE group to be the first to start their membership negotiations) won the elections in 1998, but because he did not have enough allies he had to go into the opposition, against a government made up of small parties from the centre-right to the centre left, united in the rejection of "Meciarism".

[37] Cf. the Eurobarometer published in November 2016: only 32% of the Czechs believe that belonging to the EU is a good thing for their country (only the Greeks lie below this at 31%).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :