Migration

Pascal Perrineau

-

Available versions :

EN

Pascal Perrineau

Rising Concern about Migration in European Public Opinion

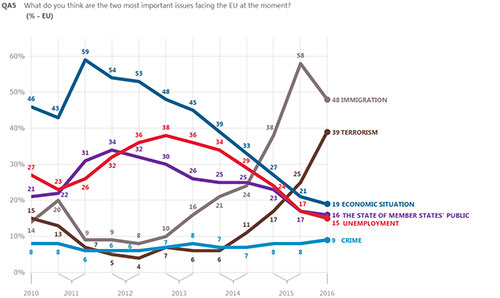

Migratory pressure, which has continued to grow since the beginning of 2015 along with the impression that European, as well as national authorities are largely overwhelmed by the management of the latter, have led to a significant return of concern about immigration [2]. When citizens are questioned about their main concerns, immigration is now top in terms of the most frequently quoted issues at European Union level.

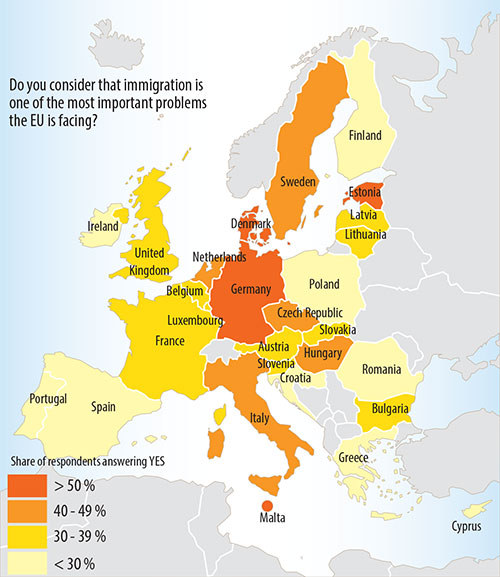

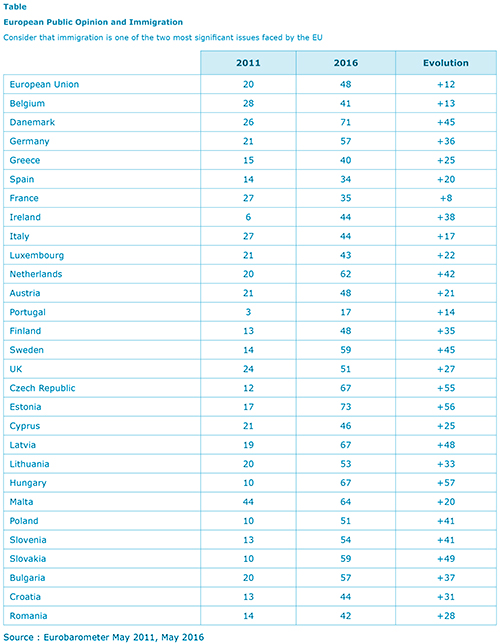

At 48% (10 points less since the previous survey of autumn 2015), it now lies far ahead of the economic situation (19%, -2 points), unemployment (15%, -2 points) and Member States' government finances (16%, -1 point). It is the most frequently mentioned concern in 20 Member States with record levels in Estonia (73%) and Denmark (71%). Worry about terrorism at European Union level has also increased significantly since November 2015 (39%, +14 points). However economic and social stakes (economic situation, unemployment, government finance, price rises) are significantly down and have been constant since 2012. In more than twenty years of surveys never has immigration been as high as a matter of concern in each of the countries comprising the European Union.

In just five years, immigration - as a major issue for the Union - rose from fourth to first place in May 2016. In 2015 the issue of immigration in the European Union has risen by 20 points.

In some countries (Czech Republic, Latvia, Hungary) the development has been extremely sharp (67%). In several European Union countries immigration has even become a major problem for an absolute majority of the population: Malta, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Sweden, Germany, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Lithuania and the UK.

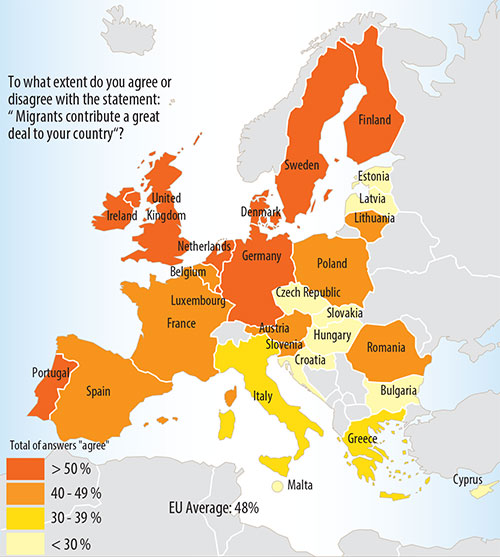

Public opinion and migration

Sources: Sources: Eurobarometer EB 83 May 2015 and "Europeans in 2014", Special Eurobarometer, July 2014.Eurobarometer EB 83 May 2015 and "Europeans in 2014", Special Eurobarometer, July 2014.

Pascal Orcier for the Robert Schuman Foundation, January 2016, © FRS.

However this rush of concern about migration has to be relativized. Although it is strong at European Union level it is still slightly weaker in terms of each national system and is clearly much lower on an individual level. In 2016, 28% of the Europeans interviewed deemed that immigration was one of the two main problems facing their country, this figure lay at 12% in 2011. Finally in 2016, 9 Member States deemed that immigration was one of the two main issues that they had to face at present, 11 Member States for unemployment. Although the migratory issue seems therefore to be becoming dominant at European Union level it does occupy a major, but secondary place in comparison with national employment, and it is only secondary in terms of the issues that people face from an individual point of view, far behind price rises, the healthcare system, unemployment, retirement pensions and even the education system. The migratory issue is significant therefore for the European Union, a major issue for many countries but it is peripheral on an individual level. There is no contradiction in this, since for many months and even years, the citizens of the European Union have had to face its relative impotence in terms of mastering this problem. After the Union, the Member States are criticised, some of them in particular, where in 2016 immigration has been a primary national stake (Malta, Germany, Denmark). Hence the European Union faces a major problem in which it might have seemed to be drifting along, not being powerful enough powerful to assert its rules, or at least a common vision amongst the various parties involved. Because of this the migratory issue is becoming a structuring element within European public opinion. The politicisation of this issue, which dates back a long way in some European countries (France, Austria, Denmark) could spread to other countries which have been little affected by national-populist trends, in which the immigrant often serves as a "scape-goat".

The Migratory Challenge and the Electoral Dynamic of National‑Populism in Europe

During recent elections nationalist and populist forces have experienced a tremendous dynamic, feeding off concern about the migratory issue amongst others. In France, the Front National lists won 27.73% of the vote in the first round of the regional elections in December 2015, ahead of the UDI / Les Républicains lists (26.65%) and clearly ahead of the PS (Socialist Party) lists (23.12%).

During the most recent legislative elections in many European countries, the nationalist and populist forces have gained ground: in Denmark, the People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti, DF) rose from 12.3% of the vote cast in 2011 to 21.1% in 2015; in Sweden the Swedish Democrats (SD) rose from 5.7% in 2010 to 12.9% in 2014; in Hungary, Jobbik, which rallied 16.7% of the vote in 2010 attracted 20.3% in 2014; in Britain UKIP rose from 3.1% in 2010 to 12.6% in 2015; in Poland, the Law and Justice Party (PiS), a national conservative movement, won the general elections in October 2015 with 37.6% of the vote, in comparison with 29.9% four years ago. In Austria, the FPÖ candidate was qualified for the 2nd round of the presidential election with 35.1%.

The rise of this type of movement has been significant in most European countries even though some (Germany, Ireland, Spain) seem to be less at risk than others. This dynamic lies in a series of factors: economic, with the difficult and costly transition of some social groups from an industrial to the post-industrial society; social, with the assertion of economic, political and cultural opening of our societies, which lies behind a certain defensive response on the part of some social groups; political, with the rejection and growing anger of many European citizens, which is feeding an anti-political feeling that national-populist movements successfully exploit [3].

To these underlying factors we can now add the migratory issue. The projection of the migratory issue to the fore in terms of European concerns is a factor that is promoting the dynamic of nationalist and populist movements, in that they have and often appear in the various national political arenas to be "anti-immigrant" parties [4]. Three Dutch academics, Wouter Van der Brug, Meindert Fennema and Jean Tillie have created an explanatory model based on a vote in support of these parties that is said to be guided by the policies put forward and based on more ideological reasons rather than being a means of protest [5]. Socio-structural developments in European societies have been quite similar and cannot explain the unequal electoral establishment of anti-immigrant parties. The concerns and demands made by voters regarding immigration have to be taken seriously, likewise the ideological proximity they declare to have, as well as the competition regarding themes that exists between the various parties in the race. When a significant number of voters takes position on the far right of the ideological spectrum, they are expressing great concern about and expectations regarding the issue of immigration and if an anti-immigrant party does not face any great competition on the part of other parties, then the likelihood of this party rallying a considerable electorate is high. This seems to be the case now in France, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria. However when this is not so (Spain, Ireland, Portugal), the electoral performance of the anti-immigrant parties is moderate.

Recently the sharp rise in concern over migration, the establishment of structured and permanent anti‑immigrant parties in the political landscape, as well as the significant ideological shift to the right in many European countries, have comprised the factors that have fostered the dynamic of these parties in the most recent general elections, as well as in surveys on voting intentions in upcoming elections (for example the presidential election in France in 2017 [61]).

The Anti-Immigrant Parties and their Discourse on Immigration

A comparative study of certain of these parties' programmes shows the central role played by the theme of immigration. Of course all of these parties, as they have evolved and become established in their respective political systems, have widened their political and ideological offer to economic, social and political issues, but the central themes of their début (immigration and security) continue to form the core of their programmes. Most of the time immigration is presented as a threat and many parties deny that their countries have any vocation to receive foreigners. Marine Le Pen, in a speech at the Front National's Summer University in Marseilles on 6th September 2015 declared "Immigration is not an opportunity, it is a burden." In the Dansk Folkeparti's programme we can read "Denmark is not a country of immigration and never has been. Therefore we cannot accept a multi-ethnic transformation of the country." [7] The same declaration can be found in the programme of the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ): "Austria is not a country of immigration. This is why we advocate a family policy based on the birthrate." [8] In line with the refusal to design a demographic policy on vigorous net migration, these parties advocate measures to restrict legal immigration drastically and to eliminate illegal immigration. For example the Front National's programme provides for a "reduction of legal immigration over five years from 200,000 entries per year to 10,000", a "drastic reduction in the number of asylum seekers, bringing illegal immigration down to zero by systematically expulsing those without papers [9]." In Switzerland the Democratic Union of the Centre (UDC) which just won 29.4% of the vote cast in the last general election in October 2015 (+2.8% in comparison with 2011) advocates "slowing immigration" and to stop all types of support to and the legalisation of illegal immigrants [10]. According to the Democratic Union of the Centre "unless immigration is controlled in less than 50 years there will be more foreigners in Switzerland than Swiss themselves." The True Finns (Perussuomalaiset, PS) advocate relinquishing the dominant idea of the last 25 years whereby "immigration and multiculturalism were the necessary and desirable ideas [11]". In their opinion this justifies Finland's refusal to share the burden of receiving some of the refugees initiated by the European Union, because in their opinion, the asylum procedure "has become the biggest modus operandi for migrants whose identity as being "persecuted" is often far from clear." The immigration against which these parties are calling for people to protest is also criticised because of the cost it is said to incur on government budgets. The Front National estimates this cost at 70 billion € per year. The True Finns criticise the cost of the personnel taken on by the State and local authorities to manage immigrant populations. The UDC stigmatises "social profiteers and other parasites", and denounces the "constant rise in asylum linked costs".

Independent of the question of cost, all of these parties insist on the danger that immigration causes to national identity. The Austrian FPÖ insists on "the European values of Christianity, Judaism and of the Enlightenment," which need to be defended against "fanaticism and extremism". The Dansk Folkeparti maintains: "Christianity finds secular blessing in Denmark and is inseparable from the life of the people. The meaning of the Christian faith, both yesterday and today, is infinite and marks the Danes' way of life." The UDC states that "the legal regime and Christian, western values that mark Switzerland must be respected by all," and it refuses "any concession, however modest in appearance, that might encourage, even in a small way, the establishment of ideas parallel to the law." Of course behind these recommendations lies the rejection of Islam and its claims on the heart of European society. As Oskar Freysinger, National Councillor for the UDC, declares "by admitting the segregation of groups, notably of the Muslim population by means of laws of exceptions, in shape of separate cemeteries, separate swimming lessons, forced marriages, we are preventing them from drawing close to our cultural heritage so that the much vaunted concept of integration is but a pro-forma exercise."

Finally, the recent migratory flow is all the more criticised since it is seen as a vehicle for penetration by terrorist elements. Hence in a speech in Marseilles Marine Le Pen attacks "Islamic fundamentalism that we are increasing by uncontrolled immigration." As for the leader of the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV), Geert Wilders, he said in May 2015 that "although all Muslims are not terrorists, nearly all terrorists are Muslims."

The Marker of Radical Islam

Here we can see how a political and ideological offer regarding immigration - and particularly Muslim immigration - has gradually grown over the years, progressively meeting an electoral demand on the part of the citizens, who are increasingly worried about migration and the development of radical Islam. The latter, which has been constantly rising over the last decade, has been of increasing direct concern for various European societies (attacks in France, Spain, UK, Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands) and over the last few months has met with the challenge of the migratory shock, the epicentre of which lies in the heart of the Muslim Middle East, which has been torn apart by inter-religious conflict and fanaticism.

These two situational factors have kindled or rekindled the anti-immigrant parties, whose political and ideological offer articulates around real expectations from large segments of the population. For example in France the survey Fractures françaises shows that 49% of those interviewed deem that the Front National is a "useful party", 34% that "it puts forward realistic solutions"[12]. At the same time 41% of those interviewed hold the opinion whereby "even if it is not its main message, Islam carries with it a seeds of violence and intolerance," 54% of the same people think that "the Muslim religion is not compatible with the values of French society," 67% think that "there are too many foreigners in France", 71% that it is not normal "for school canteens to serve different dishes according the pupils' religious beliefs," 72% that the Muslim religion "tries to impose its way of functioning," 81% that "the issue of religious fundamentalism is an increasingly worrying problem which needs to be addressed seriously."

It is easy to see on this basis that anti-immigration parties have a major potential for electoral recruitment, especially at a time when traditional politics are suffering a crisis and are making way for movements that are riding on a new split that is typical of our open societies - between the "national" and the "cosmopolitan" [13]. The very image of the immigrant, a symbol of mobility and the erosion of the borders has come, in this context, to symbolise the crystallisation of concern and reticence of whole swathes of our societies about globalisation; this is all the more the case since the otherness of the immigrant is sometimes added to that of the cultural otherness of a religion, rightly or wrongly deemed to be distant and critical of the host culture which is sometimes defined as that of the "miscreants (kâfir) and the crusaders".

[1] : This text was originally published in 'Schuman Report on Europe, the State of the Union 2016", Lignes de Reperes editions, March 2016

[2] : See the file on "Migration" in "Schuman Report on Europe, The state of the Union 2016", Lignes de Reperes editions

[3] : Cf. Pascal Perrineau, " L'extrême droite populiste : comparaisons européennes ", p. 25-34 in Pierre André Taguieff, dir., Le retour du populisme. Un défi pour les démocraties européennes, Paris, Universalis, 2004

[4] : Wouter Van der Brug, Meindert Fennema, Jean Tillie, "Anti-immigrant parties in Europe : Ideological or Protest Vote ?", in European Journal of Political Research, 37, 2000, p. 77-102.

[5] : Wouter Van der Brug, Meindert Fennema, Jean Tillie, Why some anti-immigrants parties fall and others succeed ? A two- step model of aggregate electoral support, Paper, University of Amsterdam, 2005

[6] : Dans un sondage IFOP réalisé du 9 au 10 octobre 2015 pour le Journal du Dimanche auprès d'un échantillon national représentatif de 1003 personnes représentatif de la population française âgée de 18 ans et plus, 31 % des personnes interrogées se disent prêtes à voter en faveur de Marine Le Pen.

[7] : Cf. Le programme de principe sur le site du Parti du peuple danois

[8] : Cf. Programme du Parti FPÔ adopté lors du Congrès à Graz en juin 2011.

[9] : Cf. le projet de Marine le Pen sur le site du Front national

[10] : Programme du Parti 2015-2019, UDC Le parti de la Suisse ; Document de fond : L'Islam et l'État de droit (par Oskar Freysinger) UDC pour une Suisse forte ; L'intégration n'est pas un libre-service, Document de fond de l'UDC, août 2013.

[11] : The Finns Party's Immigration Policy, The Finns Party ; The Finnish Parliament Elections of 2015.

[12] : Gérard Courtois, Gilles Finchelstein, Pascal Perrineau, Brice Teinturier, Fractures Françaises (1), Paris, Fondation Jean Jaurès, 2015.

[13] : Pascal Perrineau, dir., Les croisés de la société fermée. L'Europe des extrêmes droites, La Tour d'Aigues, Editions de l'Aube, 2001.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :