supplement

Thierry Chopin,

Claire Darmé,

Sébastien Richard

-

Available versions :

EN

Thierry Chopin

Claire Darmé

Sébastien Richard

The letter sent on 10th November by David Cameron to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk [1], detailed his demands: a desire to protect the interests of States which are not members of the euro area compared to those that do belong to the euro area, deepening of the single market in order to permit greater competition and growth, increased role played by national parliaments with regard to controlling European decisions, obtaining the right to withdraw from the objective of an "Ever closer Union" and, finally, a limitation of the rights of European migrants to receive social benefits in host countries. To what extent are these demands acceptable by London's partners? How far are the latter willing to go to keep the United Kingdom in the EU? When D. Cameron asked, in December 2011, that British financial services be exempt from common rules in exchange for his country's support for the budgetary Treaty (TSCG), his European partners saw his suggestion as blackmail and refused to pay any attention to it.

Over and above the issues linked to the negotiation that could come to a conclusion during the European Council meeting on 18th and 19th February, the question of the articulation of the European Union and the euro area remains a key question. Repeated meetings between Heads of State and government in the euro area since the start of the crisis have highlighted, according to many observers, the gap that appears to be getting deeper between the euro area and the rest of the Union. The crisis would thus seem to be resurrecting the spectre of a "multi-speed Europe" and, in this context, the question of a "variable geometry" Europe must be returned to. With the crisis we are entering a period of re-establishment of the euro area and of the European Union which must at the same time endeavour to respect as far as possible the imperative of a coherent whole. The time has come to open this debate because the crisis has made necessary work on a rationalisation and clarification of the European Union in order to realign institutions with the two major levels of integration: participation in the internal market and participation in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The British question provides an opportunity to do so and it is within this general viewpoint that relations between "the two Europe" should be analysed.

1. The European Union has a currency : the euro

A British demand that goes against the European political project

The letter sent to the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, on 10th November 2015 by British Prime Minister David Cameron details new demands with regard to the European Union, attempting to make derogation in terms of monetary policy a common rule. The European Union would thus become a "multi-currency" community, which would involve a revision of Treaties, improbable in the short term. From London's point of view, it is a matter of preventing "discrimination by currency" and the supposed pre-eminence of States that are already members of the euro area over all the others. In the speech he gave the same day in Chatham House [2] the Prime Minister called for the establishment of a British model of belonging to the European Union which would be applicable to any State that is not a member of the euro area.

The principle of a "multi-currency" community goes against the European policy project as defined since the Maastricht Treaty (1992). The transformation of the EEC into a European Union is intrinsically linked to the establishment of a common currency. In this respect it is necessary to go beyond the mere economic ambition of the single currency project (reducing monetary instability and reducing the costs of exchange operations in order to reinforce, in both cases, integration of the internal market) in order to take the measure of its political dimension: the currency, of regal authority, embodies a form of sovereignty. Transferring the privilege of minting currency to European level bears witness to a desire to strengthen European integration by sharing one's sovereignty a little more, as well as further expressing within international commerce the role and place of the European Union as the world's leading trading power. The euro is the world's second largest reserve currency. The euro area is not merely an improved European monetary system. It is no surprise under these circumstances that there is no legal provision that governs exit from the euro area. The political integration project involved with EMU could be halted by any such exit. Only an exit from the European Union in fact puts an end to participation in the euro area.

This means that the euro is much more than a currency. The current crisis highlights the unfinished state of the building of Europe and of the euro area: its Member States are at the ford, having left the riverbanks of national markets and monetary policies without yet having reached the other side, that of budgetary integration and a common voice embodied by clear political leadership with strong democratic legitimacy. The crisis thus offers an opportunity to complete the monetary integration project at budgetary, banking and political levels, including in social and fiscal terms. It is not so much a question of presenting this option as a variation of the objective, and in reality of the federalist ideal, of an ever closer Union, as stated in the introduction to the TFEU, but rather as the objective of a "more perfect Union" [3] i.e. a completed Union whose architecture would present a strong coherent whole, in order to be capable of resisting the shocks to come.

This should lead to encouraging stronger integration within the euro area. The will to create a real single market had implications on the decision to establish a single currency and, under the effects of the crisis, monetary union produces gearing effects. In this perspective the crisis provides an opportunity for deepening EMU [4] providing for budgetary and economic union reinforced by financial solidarity and real banking union, all of which based on increased democratic legitimacy, notably with a stronger association between national parliaments and the European Parliament in terms of economic and budgetary supervision. In the end the question will be to know whether a more integrated monetary should have a political dimension, including in diplomatic and defence terms, for example in the form of "structured cooperation" in this latter area.

The United Kingdom's derogation with regard to the euro: an exception, not the rule

With regard to relations between the euro area and the European Union, the British government wants to protect the interests of those States that are not members of the euro area by obtaining guarantees that EMU countries will not impose on the others measures that are considered to be contrary to their interests. Within a context where the question of continuing with integration of the euro area is again on the agenda [5], the question of protecting Member States' rights also arises.

EMU members as well as "pre-in" States (Member States wishing to adopt the euro) could thus specify their legal obligations with a view to fair treatment between States that are members of the euro area and those that are not [6] : respect for what has been achieved by the community, respect for the legal primacy of the Treaties and Union law, guarantee of the transparency of their activities, the right of States wishing to join the euro area to participate in euro area meetings. [7] Nevertheless, strict limits must be put on these demands. It is clear, for example, that recent proposals aimed at removing the obligatory nature of adoption of the single currency are unacceptable: 26 Member States have committed to adopting the single currency when they meet the required conditions, by virtue of article 3.4 of the treaty. The proposed compromise presented by Donald Tusk on 2nd February 2016, gives nothing on this point. Countries that are not members of the euro area must not create any obstacles to its extension either [8]. In an appendix to this document, the president of the Council specifies that a mechanism could be put in place allowing non-member countries to contest a Council decision that is in principle limited to the euro area which could lead to a form of discrimination [9]. A qualified majority of non-member States, not yet specified at this stage, is required in order to implement this mechanism. If it is reached the Council must then find a solution that is satisfactory for all parties. This mechanism will not, however, constitute a right of veto, preventing in particular the integration of a new member State into the euro area or delaying urgent decisions made necessary due to a financial crisis.

Article 3-4 TFEU provides that "The European Union establishes an economic and monetary union whose currency is the euro". Non-participation in the EMU therefore comes under the derogation regime: the countries concerned do not yet meet the 5 convergence criteria set forth in article 140 of the TFEU - this is currently the case of 7 Members States - or benefit from an exemption, which is the case for Denmark and the United Kingdom. Two protocols annexed to the Treaty detail the terms of this opt-out. Sweden does not benefit from a derogation but chose by a referendum held in 2003 and then again in 2007 not to adopt the single currency and has not therefore joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (MCE II) between the euro and national currencies, a condition to meet in order to be able to join the euro area in the long term. The economic and financial crisis has not, moreover, dissuaded 4 countries from joining the euro area since 2008: Slovakia on 1st January 2009, Estonia on 1st January 2011, Latvia on 1st January 2014 and Lithuania on 1st January 2015. The 7 other countries do not operate within MCE II. Bulgaria (which uses a fixed exchange rate with the euro), Croatia, the Czech Republic and Romania are hoping to join the euro area within the coming 3 to 7 years. Only the Hungarian and Polish governments - since the change of government in Warsaw in October 2015 - are showing any kind of reservation with regard to rapid membership of the euro area.

Only Denmark and the United Kingdom benefit from a derogation but these are two exceptions, not the rule. This derogation may furthermore appear only relative with regard to Denmark, since the Danish krone is anchored to the euro rate. Unlike the British pound, the Danish krone has been in MCE II since 1st January 1999. Currencies in the mechanism can only vary by +/-15% compared to the euro. Margins for fluctuation compared to the Danish krone have been reduced to +/-2.25%. In practice this difference rarely exceeds 0.5%.

Protocol n°15 provides that the United Kingdom is not bound to adopt the euro and that it retains its powers in the field of monetary policy, in accordance with its national law (paragraphs 1 and 3 of the protocol). The text also provides that:

- the stability and growth pact (article 126 TFEU) applies only partially since no notice (article 126-9) or sanction (article 126-11) can be imposed on it in case of excessive deficit. Paragraph 5 of protocol 15 provides that the United Kingdom "endeavours to avoid excessive public deficit"

- the Bank of England does not participate fully in the European Central Banks' System (article 127 TFEU, paragraphs 1 to 5) or in the monetary policy of the European Union (article 130 to 133 TFEU). It is not a member of the council of governors of the ECB (article 283 TFEU) and is not linked to the objective of maintaining price stability (article 282-2 TFEU). The Central Bank cannot emit any opinion with regard to British regulations that fall within its scope of competence (article 282-5 TFEU)

- the United Kingdom does participate nevertheless in the Council, which entrusts the ECB with specific tasks dealing with policies in terms of the prudential control of credit institutions and other financial establishments, with the exception of insurance firms (article 127-6)

- the United Kingdom is not involved with the question of the coordination and representation of European positions within international financial institutions and conferences (article 138 TFEU) or the setting of an exchange rate between the euro and third countries (article 219 TFEU).

It should be noted here that protocol n°16 which refers to Denmark's position with regard to EMU is much less detailed. The derogation has the sole effect of making applicable to Denmark all the articles and provisions of the treaties and statutes of the ESCB and the ECB referring to a derogation.

The letter sent by David Cameron to the president of the European Council again underlines the fact that integration into the euro area cannot take place to the detriment of non-member countries and any progress in this respect must take place on a voluntary basis. He believes that British tax payers should not have to finance operations in support of the euro. On both these points he would appear to over-estimate the legal and financial consequences of resolution of the crisis on the United Kingdom. The proposed compromise presented by the president of the European Council on 2nd February 2016 recalls the fact that emergency aid intended to stabilise the euro area is not intended to be financed by countries that do not belong to it.

Demands that do not reflect the consequences of the crisis on the United Kingdom

On a legal level the United Kingdom has not been concerned by the reinforcement of the economic and budgetary coordination mechanism within the EMU since the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis. Protocol n°15 states that the restrictive rules in the stability and growth pact, as modified by the six-pack of December 2011, do not apply. Only the objective of limiting its public deficit is mentioned, in relatively general terms, even though a drift in the UK's public accounts could have harmful consequences for the European Union (risk of contagion, self-fulfilling prophecy etc.). The Council thus observed, on 19th June 2015, that the United Kingdom did not meet the criterion of a public deficit of below 3% of GDP and pushed back the deadline for achieving this objective to 2016-2017 [10]. The United Kingdom has been the object of recommendations in this regard since July 2008. Nominal deficit was at 5.2% in 2014-2015 [11].

Like the Czech Republic the United Kingdom, is not a signatory to the treaty on stability, coordination and governance (TSCG), which came into force on 1st January 2013. The TSCG, which brings together 26 Member States, introduces notably the budgetary golden rule which limits structural deficit in the long term - excluding the effects of the economic climate - to 0.5% of GDP.

On a financial level, British participation in the mechanisms to assist countries in the euro area is exceptional. It has only happened twice: for Ireland in December 2010 and for Greece in July 2015, within the context of the European financial stability mechanism (EFSM) set up by the European Commission in May 2010. [12] The EFSM, the lending capacity of which is restricted to €60 billion (i.e. six times less than the European stability mechanism, ESM, dedicated to the euro area only), can grant its aid to the 28 Member States. The EFSM comes in addition to a mechanism set up in 2002 and intended specifically for countries that are not members of the euro area: the financial support mechanism for balances of payments. The medium term financial support mechanism allows for the granting of loans of a maximum of €12 billion to Member States undergoing difficulties in terms of current balance of payments or capital movements. Hungary and Latvia in 2008 and Rumania in 2009 have benefitted from it.

The EFSM lent €22.5 billion to Ireland, with the international aid plan reaching a total of €67.5 billion. The UK's exposure to the "Irish risk" made this participation entirely legitimate. A sign of the economic interdependency of the two countries, British participation in the aid plan for Ireland via the EFSM was coupled with a bilateral loan of €3.5 billion. [13] The EFSM intervened in Portugal in 2011, with a €24.3 billion loan.

Participation in the 3rd plan to aid Greece, set up in July 2015, was more limited. Intervention by the EFSM consisted of a 3-month relay loan of €7.16 billion intended to enable the Greek government to avoid defaulting on payments to the ECB and the IMF before the intervention by the ESM effectively came into play, planned in August. The EFSM loan was reimbursed on 19th August 2015. This participation resulted in a review of the regulations on how the EFSM operates. The change provides that, if the beneficiary is an EMU Member State, the granting of financial assistance is now subject to legally constraining provisions. States that are not part of the single currency will be fully compensated for any liability that they might incur if a default in reimbursement were to happen. In the Greek case a specific guarantee was even implemented. Intended for countries that are not members of the euro area, it comprised €1.84 billion in interest paid within the context of the programmes to buy Greek shares by the ECB (SMP programme) and euro area members (ANFA). The guarantee provided for euro area members amounted to €476 million.

Changes to the regulations meant that fields of intervention for European support funds could be specified. The financial instrument by means of which financial assistance will be provided to a Member State whose currency is the euro is, in principle, the ESM, as provided for in article 136 TFEU. Practical, financial or procedural reasons may motivate, however, in exceptional cases, recourse to the EFSM, most often prior to or in parallel to financial assistance within the context of the ESM. The proposed agreement presented on 2nd February insists, in this respect, on the need to implement a mechanism allowing for full reimbursement made to countries that are not members of the euro area.

2. Integration of the euro area: European convergence and national divergences

Integration of the euro area under the effect of the crisis: a clear European strategy

To regain their sovereignty over the markets, and thus the ability to decide on their own future, European States, notably those in the euro area, understood that they had to consolidate EMU. Financial solidarity mechanisms were therefore set up and the ESM came into force. Stricter common rules on budgets were also adopted and economic governance mechanisms were strengthened. The banking union project moved forward, which led to the creation of a European supervision authority entrusted to the ECB and to an agreement on a truly European banking resolution mechanism.

At the European Council in June 2015, Jean-Claude Juncker presented a report entitled "Completing the EMU", which was prepared in close collaboration with the presidents of the European Council, the Eurogroup, the ECB and the European Parliament [14]. Economic strategy was reaffirmed: macroeconomic and financial supervision must be exercised at European level; financial integration must be continued (complete banking union - creating a guarantee system for deposits made by savers - and launch of the capital markets Union); and it is essential to re-create convergence between euro area members by adopting a common set of top level standards such as, for example, on certain aspects of fiscal policy like the company tax base.

In addition, this strategy is specified and clarified: for the euro area to do more than "survive" and for it to "prosper" further steps must be taken in order to complete and consolidate it. Now this implies transition from a governance system through rules for the elaboration of national economic policies to a regime of increased shared sovereignty within common institutions based on sufficiently strong political legitimacy and responsibility mechanisms.

This is a welcome clarification. It must be hoped that heads of State and government will subscribe to it and will quickly put into practice the recommendations contained in this report. Implementation of this report has already started, as shown by the proposals adopted by the European Commission on 21st October 2015: creation of a system of euro area competition authorities; reinforced implementation of the procedure on macroeconomic imbalances; increased attention paid to performance in the social and labour fields and closer coordination of economic policies within the context of a renewed European semester; creation of unified representation of the euro area within international financial institutions such as the IMF, and completing banking Union with the creation of a single deposit guarantee scheme.

In this regard, progress on integration of the euro area, notably at budgetary level, poses the question of greater differentiation on a political and institutional level. For example, in order to reinforce the legitimacy and democratic control of European decisions taken concerning EMU, the question has been raised of an assembly specific to the euro area. The European Parliament would clearly prefer that this assembly does not compete with it and that it should be one of its sub-formations, similar to the way in which the Eurogroup is already a sub-formation of the Council and the euro area summit is a sub-formation of the European Council.

But divergence amongst national governments

Yet there are disagreements in terms of economic and budgetary union, notably on European interference in national decisions and on the opportuneness of a budget for the euro area. Also, the United Kingdom's position, outside the main budgetary coordination mechanisms, does not prevent it from being a stakeholder in most of the files dealing with financial integration without it having, it would appear, to face any real united opposition from members of the euro area.

Completion of banking Union, with the implementation of a common deposit guarantee mechanism, is not, for example, the object of any unanimous agreement within the euro area, take for example the reservations expressed by Germany. The establishment of the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) has also aroused opposition that goes beyond mere membership of the euro area. This has brought about a rapprochement between Austria, Finland, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Romania who are demanding the implementation of national approval procedures before mobilising the SRF.

Moreover, the example of transposal of directive 2014/49 dated 16th April 2014 relating to the deposit guarantee scheme, and according to which any savings of less than €100,000 placed with a banking establishment in the European Union can be concerned by a banking restructuring measure shows fracture lines between governments that do not correspond to the contours of the euro area. In November 2015, 11 countries transposed this mechanism in full into their national law, including 5 States that are not members of the euro area (Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Hungary and the United Kingdom) [15], a sign of the lack of reticence with regard to a text that is one of the bases of banking Union and with which they are not involved. It is well known that the British "taste for subsidiarity" is actually demolished in practice since the United Kingdom was one of the first to have transposed the text. The subtlety of drafting of Protocol n°15 also allows the United Kingdom to benefit from the provisions of article 127-6 TFEU which gives a specific role to the Council in terms of prudential control of credit institutions and other financial establishments, excluding insurance firms.

Then, just like banking Union in which it is not bound to take part [16], projects to further financial integration within the European Union divide the euro area more than they marginalise the United Kingdom. The plan to tax financial transactions is quite emblematic in this respect. The European Commission's plan of September 2011 [17] did not receive unanimous agreement from the Council. The United Kingdom was mobilised against this text since it was liable to impact its financial markets, the City. 11 States, who are members of the euro area, got together to set up greater cooperation on this subject on 9th October 2012. [18] This situation calls for two remarks:

- this plan was not unanimously received in the euro area since the number of participant States is less than the number of countries that have adopted the single currency;

- for the time being this project has not yet come to fruition, an additional indication of a lack of unity within the euro area on matters such as tax base or territoriality.

In addition the project for European regulation on the separation of banking activities also highlights the fact that euro area members are far from having a single vision of how European standards should be drawn up for financial matters [19]. The text aims to distinguish retail banking activities from investment banking. It provides for a ban on negotiation for own account and the retaining of certain negotiating activities for major European establishments. Yet the regulation, once adopted, will not apply to British establishments since article 21 provides for a derogation for credit establishments covered by national legislation with an effect equivalent to that of the regulation. This derogation will be granted by the Commission at the request of the Member State concerned, which must have received a positive opinion from the national authority with jurisdiction, responsible for surveillance of the banks for which the derogation is requested. In order to meet the derogation conditions, national legislation must have been adopted before 29th January 2014, i.e. the date of presentation of the draft regulation. National legislation must meet three criteria:

- the law must aim to prevent financial difficulties, bankruptcies or systemic risks;

- the law must prevent credit establishments receiving eligible deposits from individuals and SMB from carrying out regulated investment negotiation activities as principle party and from holding assets for negotiation purposes, exceptions may exist;

- if the credit establishment receiving eligible deposits from individuals and SMB belongs to a group, the law guarantees that this credit establishment is legally separate from group entities that carry out the regulated investment negotiation activity as principle party or which hold assets for negotiation purposes.

This exemption is specifically aimed at the United Kingdom which adopted in 2013 a legislative mechanism (The Banking Reform Act) which meets these criteria.

Finally, in the coming months analysis should be made of the debates around the project for capital market Union, presented in the name of the European Commission by the financial stability, financial services and capital markets Union commissioner, the British man Jonathan Hill. The CMU meets several objectives: diversification of sources of finance, better sharing of risks between the private sectors of Member States and greater integration of security and share markets. The stated ambition is to have financial establishments with structures adapted for risk management. The so-called 5 presidents' report on extension of EMU considers that, along with banking Union, this is one of the two pillars of a necessary financial union [20]. It is not limited, however, to the euro area only. The outlines of the project remain blurred, nevertheless, although a green paper was published in February 2015 [21]. The consultation undertaken for the drafting of this document does however translate real involvement on the part of the British: 22% of the 474 answers given come from the United Kingdom. The question of a review of the method of functioning of banking Union, with the establishment of a European financial markets supervisor, should be at the heart of discussions with the United Kingdom. It is no doubt in the light of this prospect that analysis should be made of the British wish not to allow its position to be dictated by the euro area.

3. The euro area: a homogenous block during votes at the Council and the European Parliament?

Votes at the Union Council

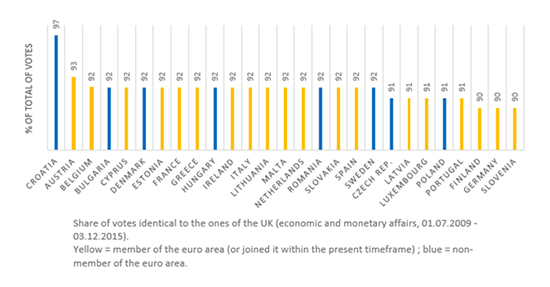

Within the Council, coalition structures on economic and monetary matters confirm the lack of any "block" dynamic amongst euro area countries. Graph 1, created using the Votewatch database shows the political culture of consensus within the Council and the place of the United Kingdom within it. It presents, for the period from 1st July 2009 to 31st December 2015, the share of votes cast by each Member State in the field of economic and monetary affairs and which is similar to those of the United Kingdom. The high share of percentages presented (between 90 and 97% of common votes between the Member State studied and the United Kingdom) is a good illustration of the fact that, although increasingly taking decisions by vote, the Council is a body with a strong culture of consensus where putting members in a minority is the exception rather than the rule, and of an active network of negotiation between European capitals which also includes countries that are not members of the euro area [22]. It is therefore already surprising to even look for a block structure here, as this is something that goes against its practices. So, although the Cameron government has opposed its peers in the Council more often than the Brown government, [23] it has only gone 4 times against a proposed text on this subject at the Council, from a total of 81 texts voted. Even if the scale of difference were higher, the graph shows a lack of correlation between proximity with the United Kingdom during votes and the fact of whether the Member State in question belongs, or not, to the euro area. There is not therefore any reason to conclude as to the presence of a block vote by the euro area unfavourable to UK preferences within the Council on economic and monetary matters.

Data: Votewatch.eu

Data: Votewatch.eu

The so-called "discrimination by currency" thus refers to a somewhat Manichean acceptance of the reality of negotiations at the Council. It overestimates the unity of at least one of the two groups, if not both of them.

As an example, the compromise adopted at the ECOFIN Council on 19th June 2015 provides for the implementation of a so-called negative area under the terms of which establishments whose deposits represent less than 3% of the total amount of assets or are less than €35 billion, are exonerated from the mechanism. Here again this derogation favours certain establishments in the City, such as country investment bank subsidiaries or certain mutualist banks. The procedure for authorising the exemption in case of equivalent legislation is made less complex: a Member State wishing to benefit from it must now simply inform the Commission that this is the case. This derogation is granted to it tacitly except in cases where the Commission judges, within three months, by an implementing act, that the national law does not comply.

This derogation regime does not fail to arouse questions as to the objective of integration and harmonisation of the internal market, at the very time when the British Prime Minister states his ambition to be to protect the integrity of the single market. A mechanism such as this also asks the question of the regulation's very raison d'être. Can there be justification for the use of a regulation that is directly applicable in all Member States [24] ? This type of mechanism could therefore constitute a precedent, with real risks of discordant applications of the regulation. It may amplify the distortions of competition and their consequences on the competitiveness of the European financial sector [25].

Votes in the European Parliament

The same issues are found at the European Parliament. An approach by level, firstly that of the parliamentary groups and then that of the elected members comprising them, raises the question of euro area cohesion at the European Parliament and of a possible "discrimination by currency".

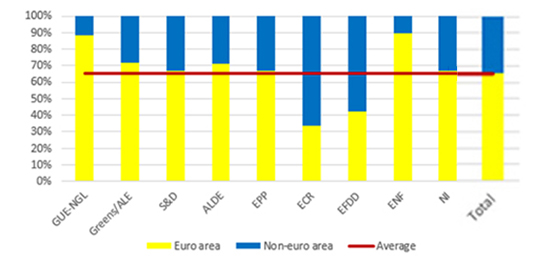

Firstly, the composition of groups in the European Parliament during the 7th and 8th legislatures indicates a nearly homogenous distribution of parliamentarians from euro area countries in the various groups (excluding ERC and EFD, see graph 2). This observation allows us to note the diversity of political and partisan affiliations amongst parliamentarians from euro area countries.

Distribution of MEPs within groups during the 8th legislature [26]

Data: European Parliament | Graph: Claire Darmé

Data: European Parliament | Graph: Claire Darmé

If the hypothesis of a block vote by the euro area were to be proven, one could then expect that the internal cohesion of the groups would be positively correlated to their composition in terms of members belonging to the euro area, since more parliamentarians from the euro area would be equivalent to more parliamentarians voting in an identical way. Linear regression tests and then the search for non-linear regression [27] do not, however, enable one to conclude on a solid relationship between these two variables, whether in a general way or in the field of economic and monetary matters. It would therefore appear to be rather improbable that the hypothesis of a "block" made up of parliamentarians from the euro area within the European Parliament can be proven. To take this question further it is necessary to look at individual level, that of the MEPs themselves.

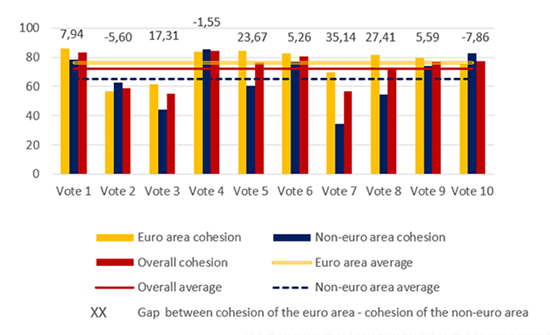

To do this we selected 10 votes [28] taken between July 2010 and October 2015 in the field of economic and monetary matters. With a concern for coherence in view of the comparison of results, we then applied to these votes the formula used by Votewatch to calculate the cohesion of a group studied [29], by dividing the European Parliament according to whether its members did or did not belong to the euro area. The result of this approach, on the votes studied, is shown in graph 3.

Cohesion of votes within the euro area, of MEPs from outside the euro area and for the whole of the EP

Data: Votewatch | Calculations and graph: Claire Darmé

Data: Votewatch | Calculations and graph: Claire Darmé

This graph demonstrates several points. Across all these 10 votes, the average of euro area cohesion is higher than that of cohesion amongst MEPs from countries that are not members of the euro area. This means, in other words, that the vote of MEPs from countries in the euro area is on average slightly more united than that of MEPs from countries that are not members of the euro area for these votes. This difference of around 10 points (out of 100) reminds us that it would be inappropriate to consider that there is a sort of minority block comprising MEPs from non-euro area countries, and with shared preferences [30]. It then leads one to wonder, in detail, about the votes with the largest differences. The aim will be to see whether they reflect a "domination" of the euro area over the rest of the European Parliament in the particular cases linked to the management of economic and financial crises.

Cohesion of the euro area is notably higher (a difference of over 10 points) in vote 3 [31], vote 5 [32], vote 7 [33] and vote 8 [34]. One first remarks that most of these votes (3, 5 and 7) constitute for the two "sets" of MEPs times of the lowest cohesion, below or well below their usual average. We are going to study the votes identified in this way - i.e. those with the most remarkable differences between the cohesion of MEPs from countries in the euro area and the others - in order to see whether they are exceptions to what would appear to be the rule at this stage in the analysis: a euro area that is not particularly subject to "block" logic.

Vote 3 concerned the definition of requirements applicable to the budgetary frameworks of Member States. Analysis of this vote does not show any fracture line between the euro area and the European Union; this is for two reasons. Firstly, the text was negotiated and presented by Vicky Ford (UK, ECR). Secondly, and following on from this first observation, the ECR group was part of the majority calling for a vote in favour of the text, although the greater part of its members are not from countries in the euro area [35], a fact that resulted in rebellion by almost half its members (25 of the 55 members concerned). The S&D group and its many MEPs from the euro area were not part of the majority and witnessed rebellions in favour of the text (62 from countries in the euro area, 24 from countries that are not euro area members from a total of 184 members). Both support for and obstacles to adoption of the text came, therefore, in a rather indistinct way from MEPs from euro area countries and from the others. That explains, moreover, the low degree of cohesion between these two groups with regard to this text.

Vote 5 involved financial services. Once again, the rapporteur was from the United Kingdom, namely Sharon Bowles from the Liberal Democrats party. One can already deduce influence on the procedure from States that are not members of the euro area. The majority comprised the groups EPP, S&D, ALDE, Greens/EFA and EFD. Most of the rebellions from MEPs from euro area countries occurred through voting against the text (10 votes against from a total of 14). This was the case even in groups that had given abstention as their voting instruction, such as the GUE/NGL group. MEPs from countries outside the euro area are characterised by a splintered vote, since 20% preferred to abstain, which explains the low degree of cohesion amongst this group on this vote.

Vote 7 on governance within the European Union is marked by a low degree of cohesion overall within the European Parliament. This text was brought by two rapporteurs: Roberto Gualtieri (IT, S&D) and Rafał Trzaskowski (PL, EPP). The setting up of the text would appear to reflect a desire for balance between the two groups since one was from the euro area and the other was not. The text was carried by a majority comprising the EPP, ALDE, S&D and the Greens/EFA. However, across all groups, only 15% of MEPs from countries not members of the euro area did not follow the line of their group, of whom a majority abstained (21 of 33). As an example, of the 13 British MEPs who voted against the line required by their group, almost all of them (11) chose to vote in favour of the text, according to the group's position. Moreover, only 4% of MEPs from countries in the euro area and part of the groups calling for a vote against the text wanted, despite everything, to vote in favour (2 out of 45). At the same time, 16 MEPs from countries in the euro area voted against despite the fact that they belonged to a group in favour of the text, i.e. 4% of the group concerned (plus 11 abstentions). As in previous cases, the voting logic does not appear to have been influenced in any definite way by membership of the euro area.

Finally, for vote 8 on the European System for Financial Supervision, only 3% of the total number of MEPs from countries that are not part of the euro area and who were in groups that were part of the majority in favour of the text, sought to vote against the text: this was the choice made by 6 MEPs, all from the EPP, of the 186 MEPs in the group from countries not in the euro area. On the other hand, 20% of MEPs from euro area countries and part of groups that had not joined the majority, rebelled and voted in favour of the text (9 votes from the 47 MEPs concerned, plus 8 abstentions). Although mobilisation of the euro area was therefore greater than that of MEPs from non-euro area countries, this must be relativized because the majority the vast MEPs from the euro area still preferred to follow the line of their group, including when the latter was not in favour of the text put to the vote.

Overall, the hypothesis of the adoption of texts in block by the euro area, specifically in the area particularly dear to the United Kingdom that of economic and monetary affairs, is not confirmed. This feeling is corroborated by a study of the data available on the loyalty of MEPs to their group or to their party, depending on their membership of the euro area, which does not show any influence of the latter on their behaviour in this regard either [36]. Some studies have shown, however, the possibility of the emergence of a coherent vote by MEPs from the euro rea on votes linked to the crisis. With the aim of not dismissing any hypothesis we applied to the 10 votes studied the protocol of one of these studies [37], in order to show up any clusters [38] which could call our conclusions in to question. It appeared that our results did not show any division between the euro area and the rest of the Parliament in such a clear way as in the original study. This can be explained in several ways, for example by the long timeframe of the votes chosen here (between 2010 and 2015 compared with 2010 and 2012 in the previous study). Taking account of abstentions can also nuance the analysis of a balance between the influence of political parties and membership of the euro area, a fact that is verified here when, on several occasions, rebels from political groups preferred to abstain rather than oppose their group head on (see analysis of vote 7). Finally, a distinction between MEPs from the left and the right, used in order to reduce the weight of the political leaning factor, showed a real difference between the distributions of MEPs according to their political parties. On the right the clusters, i.e. groups close to each other politically, reflected membership or not of the EPP; on the left the euro area and MEPs from countries not in the euro area were extensively mixed together.

None of the elements studied within the context of this study allows for a conclusion that strictly agrees with the hypothesis of a euro area block vote in the European Parliament. It would appear that the determining factors in the way MEPs vote, just like the determining factors in the political choices of government representatives, are mainly dictated by considerations other than their membership, or not, of the euro area. [39] Moreover, and despite low level influence by British MEPs as a national delegation in votes [40], discrimination by currency that would mean the ostracizing of MEPs from countries that are not members of the euro area on economic and financial matters, would also appear to have to be dismissed, particularly in view of the profiles of the rapporteurs of the texts presented [41].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the demands made by British Prime Minister David Cameron and concerning the euro do not reflect either the spirit of European treaties or the reality of the way in which relations between the euro area and the European Union operate. What is true for the principle of freedom of movement, that is the reticence of the United Kingdom's European partners to call into question the foundations of this achievement [42], is also true for the construction of the EMU: it would be regrettable if, on these questionable bases, the European Union were to go back on its essential principles.

Click here to see the appendices

[1] : David Cameron, "A new settlement for the United Kingdom in a reformed European Union"", 10th November 2015. : https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/475679/Donald_Tusk_letter.pdf

[2] : David Cameron, speech for a reform of the European Union, 10th November 2015: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-speech-on-europe

[3] : Mario Draghi, "Europe's pursuit of a 'more perfect Union'", Harvard Kennedy School, 9 October 2013 - http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2013/html/sp131009_1.en.html.

[4] : The euro area is already of continental dimension, with 19 States and 338 million inhabitants - other States are yet to join it - and represents almost 75% of GDP of the European Union.

[5] : At the European Council in June 2015, Jean-Claude Juncker, presented a report entitled "Completing the European EMU". For a recent Franco-German contribution on this subject, see the tribune by Emmanuel Macron, French Economy Minister and Sigmar Gabriel, German Vice-Chancellor, "Europe: pour une Union solidaire et différenciée", Le Figaro, 3rd June 2015.

[6] : See the tribune by George Osborne and Wolfgang Schäuble, "Protect Britain's Interests in a Two-Speed Europe", Financial Times, 27th March 2014.

[7] : Cf. Jean-Claude Piris, "Brexit or Britin: is it really colder outside?" European Issue n°355-bis, Robert Schuman Foundation, October 2015, http://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-355-bis-en.pdf

[8] : Draft Decision of the Heads of State or Government, meeting within the European Council, concerning a New Settlement for the United Kingdom within the European Union (EUCO 4/16), 2nd February 2016.

[9] : Draft Statement on Section A of the Decision of the Heads of State or Government, meeting in the European Council, concerning a New Settlement for the United Kingdom within the European Union (EUCO 5/16)

[10] : The British budget year starts on 1st April and ends on 31st March. A recommendation in December 2009 indicated that the British public deficit should be below 3% in 2014-2015. Deficit objectives for the UK now are to reach 4.1% of GDP in 2015-2016 and 2.7% of GDP in 2016-2017.

[11] : They were at 7.7% of GDP in 2011-2012, 7.6% in 2012-2013 and 5.9% in 2013-2014.

[12] : (EU) regulation n° 407/2010 of the Council on 11th May 2010 establishing a EFSM.

[13] : Denmark and Sweden also granted bilateral loans to Ireland of 400 million and 600 million € respectively.

[14] : See the 5 president's report 22nd June 2015.

[15] : The Czech Republic has already transposed it in part.

[16] : For its part Denmark is wondering about participation in the single banking supervision mechanism, placed under the aegis of the ECB in coordination with national control authorities.

[17] : Proposed Council directive establishing a common system for tax on financial transactions and modifying directive 2008/7/EC of 28th September 2011 (COM(2011) 594 final).

[18] : Austria, Belgium, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

[19] : Proposed regulation on structural measures improving the resilience of European Union credit establishments dated 29th January 2014 (COM(2014) 43 final).

[20] : 5 presidents' report, op. cit.

[21] : COM(2015) 63 final.

[22] : Daniel Naurin and Rutger Lindhal (2009) "Out in the cold? Flexible integration and the political Euro-outsiders", European Policy Analysis, Issue 13, 1-12

[23] : Simon Hix and Sara Hagemann (2015) "Does the UK win or lose in the Council of ministers" http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/11/02/does-the-uk-win-or-lose-in-the-council-of-ministers/

[24] : The Council's legal department judged, in June 2014, that the exemption was contrary to the Treaty's provisions, with the ECB considering, for its part on 19th November 2014, that it should be removed.

[25] : French Senate European Affairs Commission, political Opinion on the regulation proposed by the European Parliament and the Council relating to structural measures to improve the resilience of credit establishments in the European Union, 29th October 2015.

[26] : See appendix point 1. for the distribution during the 7th legislature, which is relatively similar.

[27] : See appendix point 2. This is the stata order for the search for simple linear regression (regress), and then the order for searching non-linear regression by the Kendall rate (ktau), chosen due to the low amount of data included in this section of the demonstration.

[28] : See the list of votes in appendix 3.

[29] : The Hix-Noury-Roland formula, or Agreement index (Ai), from Attina`, F. (1990). "The voting behavior of the European Parliament members and the problem of the European parties." European Journal of Political Research, 18(2), 557–579, where Ai=(max(Y,N,A)-(0.5((Y+N+A)-max(Y,N,A))))/(Y+N+A) with Y = votes for, N= votes against and A=abstentions. see "Methodology", http://www.votewatch.eu/blog/guide-to-votewatcheu/

[30] : Ian Begg (2015) "Britain's risky euro-out strategy", http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/11/19/britains-risky-euro-out-strategy/

[31] : 23/06/2011, Requirements for the budgetary frameworks of Member States http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P7-TA-2011-0289&language=FR&ring=A7-2011-0184

[32] : Financial services: lack of progress at Council and Commission's delay in the adoption of certain proposals.http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fTEXT%2bTA%2bP7-TA-2013-0276%2b0%2bDOC%2bXML%2bV0%2f%2fFR&language=FR

[33] : Constitutional problems of multitier governance in the European Union. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fTEXT%2bTA%2bP7-TA-2013-0598%2b0%2bDOC%2bXML%2bV0%2f%2fFR&language=FR

[34] : European Parliament resolution of 11th March 2014 with recommendations to the Commission on the European System of Financial Supervision review (ESFS). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fTEXT%2bTA%2bP7-TA-2014-0202%2b0%2bDOC%2bXML%2bV0%2f%2fFR&language=FR

[35] : See appendix 1.

[36] : See appendix point 4. The data was analysed using a pairwise correlation (pwcorr) to detect possible linear correlation between variables, then by searching for the Spearman rho (spearman) to demonstrate a possible non-linear correlation, but they did not appear.

[37] : See notably Stefano Braghiroli, "An emerging divide? Assessing the impact of the Euro crisis on the voting alignments of the European Parliament", The Journal of Legislative Studies, Volume 21, Issue 1, 2015.

[38] : See appendix, point 5.

[39] : Ramunas Vilpisaukas (2013-2014) "The Eurozone Crisis and Differentiation in the European Union", Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review, Volume 12, 75-90

[40] : Simon Hix (2015) " UK influence in Europe series: British MEPs lose most often in the European Parliament", http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/12/17/uk-influence-in-europe-series-british-meps-lose-most-often-in-the-european-parliament/

[41] : In this regard it is interesting to remember that Vicky Ford, Sharon Bowles and Peter Skinner, all of whom are British MEPs, are financial text rapporteurs at the EP, which is proof of the lack of discrimination. V. Ford dealt with a planned directive on requirements applicable to the budgetary framework of Member States. Her colleague, Anthea McIntyre, also a British citizen, was a rapporteur on a text on protection under criminal law for the euro against counterfeit.

[42] : See Donald Tusk's answer to David Cameron dated 2nd February 2016 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/press-releases-pdf/2016/2/40802208284_en_635900130000000000.pdf in which the president of the European Council suggests working on the United Kingdom's demands in terms of freedom of movement by adopting a gradual and exceptional approach, rather than calling into question the very principle of freedom of movement.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :