supplement

Jean-Paul Perruche,

Patrick Bellouard,

Pierre Lépinoy,

Maurice de Langlois,

Béatrice Guillaumin,

Patrice Mompeyssin

-

Available versions :

EN

Jean-Paul Perruche

Patrick Bellouard

Pierre Lépinoy

Maurice de Langlois

Béatrice Guillaumin

Patrice Mompeyssin

For several years now the President of the USA has clearly expressed a pivot in American strategic priorities towards Asia and the Middle East, encouraging his European partners to take responsibility for a greater share in the burden of their own security. This new direction became evident during the Libyan crisis (2011), and during the subsequent Sahelian crises and also in the face of the new Russian neo-imperial policy in response to which President Obama very quickly made it clear that the military option was not possible.

In spite of the declarations and measures announced during the Wales Summit (September 2014), this development inevitably challenges the traditional functioning of NATO.

As for the European Union the limits placed on its ambition and the means for a Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in the treaties (Nice and Lisbon) have prevented it from achieving an operational level that would turn it into a credible alternative if the USA opted for disengagement.

However the reduction in the relative power of the countries of Europe in contrast to the rest of the world and notably regarding the emerging countries (BRICS), which has been accentuated by the constant reduction of their defence spending over the last 20 years, leaves them with barely no prospect of being able to conduct coercive measures alone, with the relative exception of France (on a small scale and for how long?)

The time has therefore come for awareness that in a deteriorating security context on Europe's borders and given the increasingly shared threats we face in a globalised world, there is no alternative for the Europeans but to pool their resources if they want to maintain control over their future and defend their interests and values effectively.

During her first speech to the European Parliament, Federica Mogherini, High Representative and Vice-President of the Commission made 15 commitments including one which involves the drafting of a new European security strategy. The present initiative is based on the observation that there is urgent need to update the 2003 document (updated slightly in 2008), the general nature of which is no longer adapted to the present reality in terms of the defence of Europe.

With this observation as a support the EuroDéfense team has examined the interest, and also the difficulties, the risks and the conditions necessary to complete a European White Paper on security and defence. In no way does this work prejudge the results of an exercise like this which might lead to greater integration or simply to win-win sharing resulting from subsidiarity that is fully understand and implemented intelligently. A summary of the main ideas is set out in four questions:

- Why do we need a European White Paper on security and defence?

- What obstacles have to be overcome and which opportunities can be used to do so?

- How should it be achieved: content and procedure?

- How could it be used in Brussels and in the Member States?

WHY DO WE NEED A EUROPEAN WHITE PAPER ON SECURITY AND DEFENCE?

During the European Council of 19th and 20th December 2013 the heads of State and government re-iterated the importance of a common approach to European defence and advocated a certain number of real, auditable measures to make the CSDP more effective. They set June 2015 as the date to assess progress and possibly to decide on further action. It is a clear admission on their part that the present situation is not satisfactory. However it might be feared that as in the past, this is just another declaration about what should be done but not undertaken. This is why a European White Paper defining a General Security Strategy with the capability goals to achieve, is necessary to ensure that defence and security questions remain a high priority on the agendas of both national and European leaders.

The European security system - a legacy of the Cold War that is no longer adapted to the realities of the 21st century.

The constant reduction in defence spending in Europe over the last 20 years, whilst other countries in the world (and notably the emerging states) have been increasing theirs, has led most European countries into a state of almost relative military impotence (weakness in contrast to other players) which is reflected in the inability to take the initiative for operations and the obligation to provide minimum aid to operations launched by others. It is becoming clear that individually the States of Europe, even the most powerful, are losing the will, the support of public opinion and the media, the ability and the means to engage in high risk operations. The most recent interventions in Libya and then Mali clearly showed their limits and the need for external assistance (American as it happened).

At present the American military capabilities are being redeployed across the world as shown by the directives on the American 2012 and February 2015 strategies. American commitment in Europe has decreased and the total dependency of European countries on their American ally for their defence exposes them to uncertainty. To a backdrop of a difficult disengagement from Afghanistan, withdrawal from Africa and no solution for Ukraine, NATO is experiencing an existential crisis. The issue of Europeans being able to defend their values, heritage and interests on their own in this new context is critical. However as we already indicated the present state of European defence is typified by dependency on the USA, and by the juxtaposition of heterogeneous policies that are often ill-adapted to the realities of the 21st century. The capability for joint European action is ridiculously weak in view of the economic power and wealth that Europe represents - a notorious consequence of uncoordinated defence spending.

The world security context is changing and has been declining since the start of the 2000's.

Since the 9/11 attacks in the USA to the most recent events in Paris, Copenhagen and Tunisia - not forgetting London, Toulouse, Brussels and Madrid - the threat of Islamic jihadist terrorism has grown in strength and has spread. It is now established in many zones of conflict (Iraq/Syria, Afghanistan) and also in failed or weak States (Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Sahel-Sahara), establishing a direct link between the internal and external threats to our countries.

Russia's return to belligerence, to a backdrop of armed confrontation in Ukraine, has shown that the resurgence of armed conflict in Europe is no longer an improbable hypothesis, but demands a reassessment of the defence system of the countries of Europe.

Europe's southern neighbourhood has also been severely destabilised by the aftermath of the Arab Spring, notably in the countries on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, which has led to mass uncontrolled immigration and trafficking of all types.

In Asia the rise of China has gone hand in hand with new tension, notably with its neighbours and rivalries with other major world powers.

Numerous activities in cyberspace, such as the attack on the French TV channel TV5 at the beginning of April 2015 by terrorist organisations or by States has highlighted how vulnerable our Western societies are.

To this we might add the danger of potential fighting due to the effect of climate change and difficulties in accessing vital natural resources (water, hydrocarbons, rare metals).

Europeans cannot opt out of the responsibility they have in assessing their defence requirements in the context of the 21st century.

The CSDP, operational since 2003, remains in its elementary form and is inadequate. Its results are mitigated in spite of a great number of civilian operations and military crisis management missions (around thirty) undertaken in Europe, Africa and Asia and some capability and industrial accomplishments (European Air Transport Command, A400M, MRTT, satellite programme MUSIS, etc.). Its limits and its shortfalls emerged clearly (seen Annex 1) during the recent Sudanese refugee crises in Chad, Libya, Mali, Central African Republic and Ukraine, notably illustrating a obvious lack of recognised common interests, shared ambitions and unity of action. This disappointing observation after twelve years of existence raises the issues of the effectiveness and therefore the usefulness of the CSDP. As it stands the CSDP gives barely any hope of the launch by the EU of coercive operations, even in the close European neighbourhood. Peace restoration operations (high in the spectrum of the Petersberg tasks) have never seriously been envisaged and the Battlegroups have never been used. The time has come to assess whether the European Union needs military capabilities and if so to what purpose?

A European approach to security makes sense in the present context.

Most of the threats and risks to which the countries of Europe are exposed are mainly shared even though the priorities they set may differ.

The lack of critical mass on the part of the States of Europe is evident and worrying. In the open, globalised world of the 21st century mass effect has become a criterion of power and influence. Competition between major multinationals is a good illustration of this. Any company that does not reach critical mass is doomed to be absorbed or disappear, (the most recent example was Alstom in France). To a certain degree the comparison applies to the States if we refer to the link between sovereignty and power: the weaker the States, the more dependent they are and exposed to outside pressure which exploits their internal weaknesses. The EU succeeds in asserting its standards when it speaks as one, which the Member States are no longer able to achieve individually.

The advantages of pooling forces are real: with the aim of reaching critical mass, the pooling of requirements and capabilities is an interesting path for Europeans to follow. In the area of defence the examples of the EATC in Eindhoven with the pooling of air transport capabilities of several EU countries, that of Galileo, which allows Europeans (together) to have an independent geographical positioning system and that of the transport plane A400M - all show the strategic interest of pooling. The present landscape of the defence industry in Europe and the multiple duplications of means between Member States is on the other hand the illustration of the terrible waste of fragmentation.

There is obvious complementarity between Europeans in all areas, particularly in terms of defence. Instead of opposing the interests of the countries in the south - which are oriented as a priority towards the threat coming from the Mediterranean and those in the east which are oriented towards Russia - why can we not see the complementarity of the situation that can be defined as part of an overall vision for the security of the European continent? The same applies to capabilities, in an overall European vision - we should be able to overcome weaknesses of some with the strengths of others.

Common European Defence can be founded on the adoption of common values (democracy, freedom of opinion, respect of Human Rights, the respect of minorities etc.[1]), but also on common or complementary interests. It is a particularly opportune moment to defend these together, at a time when these values and interests are being violated and threatened from without and within the continent.

THE DRAFTING OF A EUROPEAN WHITE PAPER ON SECURITY AND DEFENCE IS POSSIBLE IF WE CAN OVERCOME OBSTACLES AND SEIZE OPPORTUNITIES

It is surprising to note the reticence of European political leaders about discussing issues pertaining to defence, as seen on the agenda of the European Councils over the last few years (defence issues did not feature once on the agenda between 2008 and 2013) and we should question this:

The approach to drafting a European White Paper is already problematic which cannot be ignored; this is mainly due to some identifiable fears:

- the lack of a common foreign policy prevents the construction of a common security and defence policy; however although the States have ever decreasing defence capabilities they do not appear to be ready to converge in terms of foreign policy,

- the idea of sharing defence policies is the source of a fear of the unknown amongst the leaders of Europe and of not being able to control the consequences of an initiative of uncertain outcome, the danger of highlighting divergence between States without being able to deepen convergence. The drafting of a European White Paper would be a first initiative all the consequences of which are difficult to foresee; therefore it raises fear of playing the sorcerer's apprentice in a destabilising approach without being sure of being able to manage the consequences and contingencies. Although they admit their inadequacies and shortcomings in assuming responsibility in terms of defence, Europe's political leaders fear that a European White Paper will lead to a reduction in their freedom of action and initiative without necessarily settling their defence problems efficiently,

- the difficulty in thinking about defence together without have found prior agreement over the final outcome sought in terms of European integration (federation, confederation, simple cooperation between Nation States?) is undoubtedly the biggest obstacle. This question is naturally linked to the exercise of power (by or in the EU)? Even though we acknowledge that the European Union enjoys a certain normative power, in-depth thought about the exercise of power now seems vital; can the EU function by law without force? What sense should be given to the idea of powerful Europe? Even if the Union does not have all the features of a superpower it does enjoy some competences and attributes (economy, science etc ...)[2]. This question is intrinsically linked to the distribution of responsibilities between the national and European levels and therefore to sovereignty. The reasons behind the difficulty in thinking about power at European level are twofold: on the one hand there is the heterogeneous nature of European cultures in the exercise of power and on the other the lack of joint vision about the final nature of the EU and therefore of its ambitions. For historical reasons some States are reticent about the use of military force whilst other deem it vital. Can a balance be found between what is called "hard" and "soft power", between coercive and peaceful power? The EU does not necessarily have to become a State power in the traditional sense of the term but it must have at least have the power and the necessary means for the defence of its interests and for the promotion of its values without having to bend to the law of those who are against it,

- To this we might add the obligation of managing constraints generated by a joint approach to defence over national policies, particularly from an industrial point of view. In spite of the interest that has already been widely acknowledged across Europe of retaining a certain amount of industrial and technological autonomy, a European approach to the expression of capability requirements is the source of mistrust. It affects the protection of national defence industries (which often escape having to compete) and the freedom to purchase what one likes and when. However in order to be effective a common approach demands the coherence of capability requirements and industrial responses, which moves towards the creation of a strong, sustainable European Defence Technology and Industrial Base since the latter cannot be seen as a the simple sum of national Technology and Industrial Defence Bases. In striving towards coherence the EU has to undertake a careful assessment of unnecessary duplications, both from a capability and industrial point of view;

- Another obstacle lies in the fear of a challenge being made to NATO's exclusivity over collective defence by turning the EU into a real player in the defence of its members. The drafting of a White Paper by the EU would mean considering defence from an overall point of view i.e. without limiting its ambitions and competences to the management of crises external to its territory. To some this development might appear as a challenge to the tacit division of tasks acknowledged in the treaties (including the Lisbon Treaty),

- The need for legitimacy for a European White Paper means involving the citizens. But European awareness and patriotism do not exist; undertaking the study for the need of the defence of the European Union as a whole means acknowledging its existence as a political entity (500 million inhabitants living in a common geographical area of 4.5 million km2, producing 22% of the world's GDP). Since the final outcome sought in terms of European integration remains vague its citizens have great difficulty in seeing what the EU is. Since they have no points of reference they intuitively consider it to be a State that does not exist and disappoints them as it is incapable of providing solutions to their national problems.

The wide range of national feeling about defence also has to be taken into consideration - a legacy of the past and of history as well as geography. This is reflected in a reserved approach to the use of force and the acceptance of human losses in external engagements. Europeans in the north have an attitude that is far less focused on the employment of the military for their security; they are attached to the emergence of a world governance that protects their freedom of action without making them dependent on powerful neighbours. They invest in UN stabilisation operations and seek American support in situations that they cannot cope with. The Germans are still traumatised by the Second World War and are extremely reticent about any armed and particularly high risk engagements. The countries in the south are split over problems in the Mediterranean (neighbouring countries, illegal migration, Mafia-type trafficking) and those in the East are focused solely on Russia. Only the French and the British have retained a world ambition in terms of foreign policy and the use of armed force, including the acceptance of risk in external operations.

These fears will have to be worked upon if we want Member States to commit confidently to the drafting of a European White Paper. There are also some opportunities to be seized.

The recent development in the world situation provides us with objective reasons to reconsider the security of the European Union's members on a European level:

• the development of large terrorist bases on Europe's doorstep that are targeting the European population,

• the criticism of Western values by the Russian government and its employment of a fait accompli policy by force,

• the increase in uncontrolled immigration on Europe's borders, notably from peripheral areas of conflict,

• the rise of cyber terrorism which is threatening each European country independent of its geographic situation.

No one can ignore the rise of these threats that are affecting all Member States in some way, nor can we ignore the fact that this downturn is concurrent to the disengagement announced by our American ally.

Moreover and at the same time the Greek financial crisis has highlighted the need to establish new mutual rights and duties between States under the solidarity-responsibility diptych. Awareness of this means that thought about European defence might be more widely accepted on the part of the Union's governments.

All of these circumstances mean that in-depth thought about the organisation of European defence is opportune. Trying to avoid this issue that is fundamental for the security and prosperity of the European population is no longer an option.

Thought on this should notably include:

• the identification of risks and dangers which require a European approach (migration, terrorism); including the defence of vital interests (nuclear?),

• the definition of an improved distribution of roles between Europeans and Americans in the defence of Europe but also for the protection of our joint interests,

• the definition of strategic capabilities that the European States cannot acquire individually but which are vital to their independence and their freedom of action (like Galileo).

SUGGESTIONS AS TO THE CONTENT AND THE DRAFTING PROCEDURE OF A EUROPEAN WHITE PAPER

Regarding its content a European White Paper should express the political will of the Member States and public opinion, organise their defence on a European level, without this necessarily leading to a totally integrated European defence system (European army). The outcome of the European approach should be to provide common perspectives and solutions in areas in which nations are individually weak, not to substitute them, since acceptance on the part of Europe's citizens is key to its credibility. A short informative work, it should include detailed implementation strategies in the areas of internal and external security, with regions of the world and priorities[3].

As an introduction the main outline of developments in the world situation should be laid out in detail, notably marked by globalisation and climate change, the weakening of the influence and legitimacy of the States, along with the rise in terrorism, crime and sectarian excesses. It should show how major world balances will be weakened by the issue of vital resources, demographic disparity, the rise of China and the increase in military arsenals. A description of technological and cyber, natural and health-related, migratory risks as well as the insecurity created by economic imbalances might also be added to this.

Ir should take on board that the Europe's security environment is worsening, even though statistics overall show a reduction in the number of conflicts worldwide [4]. Although Europe has lived in peace for the last 70 years, rising threats within its territory, an increase in conflicts on its borders and in its neighbourhood, whether these involve States or not - is a proven truth.

The idea of European security should express the determination to adopt a common approach in the identification of risks and threats as in the response which needs to be given combining Member States' means and responsibilities. It would indicate that in the future Europeans will have to do together what the Americans do not want to do or what they can no longer do alone for the defence of Europe and they that must be are aware that American support will not be as "free" in the future and that our grand ally is undoubtedly expecting reciprocity regarding its commitment in Europe.

It would stress that given this new situation, Europe's response is not limited to identifying and protecting the common interests of the EU's Member States but that it aims to defend all of their interests together (shared and national).

To this end a European security strategy is necessary which goes beyond that defined a minima in the 2003 document, the guidelines of which are not concrete enough.

The new European strategy must embrace all of the Member States' defence requirements and distinguish what is shared and what is specific to each State. A European White Paper or equivalent document which lays down the outline of this strategy should define how Europeans see their security in the next 20 years: what they want to do together in this area and what they want to retain on a national level in order to address all threats. It should open the way for the rational, balanced sharing of responsibilities between States and the European level and be able to evolve. It should also take on board the relative but certain disengagement of the USA in Europe and the conditions of a renewed transatlantic alliance that is adapted to new realities.

Its drafting should give rise to an in depth debate that will lead to positions being taken on the major issues that condition European defence:

• the development of the idea of critical mass for the States' power of influence; advantages, difficulties and limits to the creation of an army acting on behalf of the European Union; obstacles to overcome. The trend on all continents is to group States in more or less ambitious organisations. But there are still many independent States which count, although they are the size of some European countries (Iran, Turkey, Israel, Japan) and even some powerful city-States which are happy with their situation (Singapore). Here we need to show how the European Union can leverage the power of European States and how a European identity can be created by superposing it on national identities without making them disappear,

• the expression of power and the use of armed force by the EU: military power taking part in international power struggles or peaceful power, privileging diplomacy and development aid ("soft power"), rejecting major coercive action?,

• the expression of solidarity in the areas of security and defence within the EU, including the possibility for a group of Member States to act on behalf of the EU as well as the harmonisation of defence spending,

• the implementation of the subsidiarity principle between the EU and its Member States in the area of defence. By the implementation of the subsidiarity principle, there is nothing to prevent the combination of national and joint action,

• the adaptation of the transatlantic link and the relationship with NATO, thereby introducing the EU as a player in defence in the transatlantic partnership and providing it with renewed impetus,

• the problem of a concerted approach to nuclear deterrence and anti-ballistic missile defence in the defence of the EU,

• the conditions for the EU's strategic autonomy to achieve its goals and the means necessary to do this (particularly in space).

For the Europeans the drafting of a European White Paper would mean:

- taking back responsibility for their own defence,

- highlighting the advantages we might expect but also the difficulties of a common approach to European defence,

- distinguishing real problems from unfounded or oriented assertions, identifying the causes and suggest solutions to overcome them,

- taking on board the perception of risks and threats by the various EU Member States and also their foreign policy ambitions,

- setting goals, capabilities, and the means at European level to ensure the defence of all States and their citizens.

The White Paper should also address the issue of the outcome of external operations that are not directly linked to the protection or survival of the States. Does the European Union have the moral responsibility to protect and rescue populations in danger? Is it a responsibility linked to its economic weight, its history? Does it have to do this only when the consequences have a clear influence over its internal security (terrorism, trafficking of human beings, crime, and the illegal movement of arms)?

The truth would emerge from this exercise regarding the reality of European defence, its potential and the conditions to be met to make it effective. With a dual approach - on the part of the EU and the States - the drafting of a European White Paper would lead to a better understanding, not only of what European mutualisation could provide to the States, of what must remain national, but also of what the States have to do to lend credibility to the European approach to their defence, notably in view of their public opinion.

As observed in the study by the Paris "Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l'Ecole Militaire" (IRSEM) in 2012 as it made an inventory of the White Papers (or equivalent documents) in the EU's Member States, there is great disparity between countries in terms of defence. To draft a European White Paper:

- A first stage might comprise putting forward a common accepted framework taking on board the requirements expressed for the drafting of national White Papers (or their equivalent),

- Then taking advantage of this preparatory work, a study should be undertaken on strategic convergence and divergence, common and specific points regarding strategy, defence goals and requirements in the Member States together with their priorities, capability requirements. This would aim to gain better knowledge of compatibility, complementarity and possible incompatibility between Member States, prior to forming greater synergy of national defence tools (pooling and sharing).

- At the same time a strategic analysis of the EU's defence requirements considered as a complete political entity (typified by its borders, its strengths and weaknesses) and the capabilities necessary for its defence should be undertaken by an independent team bringing together experts from the Commission and the Member States. The analysis should list European common interests, prioritise the threats and dangers at EU level, set a level of ambition for the foreign and defence policy. This work would lead to the proposal of a security strategy for the EU with an approach comparable to that adopted in the drafting of national White Papers.

- Finally a comparison of the analysis resulting from a compilation of the Member States' strategies and that of the EU considered as a virtual or potential State, should lead to the optimisation of role distribution between countries based on a distant goal, but which matches the final targeted outcome. An approach like this would reassure the Member States which whilst having a goal to reach would, with necessary compromise, also be free to continue at their own pace.

From an operational point of view the mechanisms that are already in place, notably those created by the Lisbon Treaty, are effective but not used enough. Some simple measures would enable them to be used better. The White Paper should highlight the continuity between internal and external security. The latter has to appear to be coherent as should any global approach to coordinating crisis management instruments with those of development and humanitarian action.

Once the legitimacy of action has been established on the basis of a declared will, a new security policy might be implemented. Engagement scenario might be developed taking on board Member States' capacity to act, likewise those of European structures, its partners like the USA as well as regional organisations like NATO and the AU. EU-UN relations would be redefined, since the dimension of legitimacy and representativeness would be laid out in detail. Civilian or military capabilities in line with the new strategy would be developed to include joint management and implementation structures. Regarding equipment and technology, autonomy and coherence would be sought, using a strong EDTIB (European Defence Technology and Industrial Base) (see Annex 4). There must be a strong principle to exclude unnecessary and costly duplications.

Finally the European White Paper should provide the means necessary for each conclusion, (as in the French White Paper of 2013): knowledge and anticipation, protection, prevention, deterrence and intervention.

It would also be interesting for the authors of the White Paper to compare what has been accomplished within the European Union from an economic and financial point of view with what remains to be done in terms of defence. For example the members of the euro zone have accepted the transfer of one of the historic attributes of national sovereignty. Could this example not be used to open up paths in terms of defence?

In addition to this the Greek crisis has highlighted the need to develop mutual warning, prevention and resolution systems for banking and financial crises that have affected the euro zone members, according to mechanisms based on the responsibility-solidarity tandem. However we can see the limits of the single currency as long as there is no budgetary and fiscal harmonisation. Undoubtedly there are lessons to be learnt here also.

At present there is no question of substituting strategic national White Papers or strategic national references with a European model but from an exploratory point of view, the aim is to add a joint vision of defence and security to the EU's Member States' national visions as a developing entity defined by the existing treaties, i.e. a political entity whatever one might say. The European White Paper might also help to update outdated national documents.

In no way would this document be legally binding ("soft law"). But it should help to lend to legitimacy to the CSDP by making it easier to understand, both for the elites and public opinion.

From a prospective point of view a possible plan for a European White Paper is put forward in Annex 5.

The European Council (via its General Secretariat) should in reference to article 26 of the TEU be the supervising authority in its drafting[5]. But the latter should draw on a wide participation by the States (governments, parliaments, chiefs-of-staff etc ...), European institutions (EEAS, European Parliament, Commission, COREPER, COPS, EMUE, military committee, EUISS, etc.) and experts from civil society. A first draft might be undertaken by a small group of military and civilian experts recognised for their experience and impartiality (Wise Pens).

HOW SHOULD A EUROPEAN WHITE PAPER BE USED?

A White Paper like this should not be a technical document but should aim to be informative, understandable by everyone and open to the man on the street.

A key element to the EU's overall approach to its defence is that it should help to promote and develop the values that are part of the preamble to the Lisbon Treaty: "inviolable and inalienable rights of the human person, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law."

The European White Paper for defence and security would not aim to replace national White Papers. It would be complementary and would respect the principles of subsidiarity regarding Member States who would retain their sovereignty and be able to choose to exercise this both at national and European level. Its use should therefore be provided for on both levels.

At European level it would form the conceptual reference framework explaining the definition of common or concerted policies: organisation, concept, formation, training, personnel, budget and equipment.

In particular it would enable the definition of regional strategies (e.g. Sahel, Horn of Africa) and themes (e.g. security, maritime, cyber-defence, energy strategies and the link between the CSDP and the Neighbourhood Policy), organisation (command and supervision), creation of the necessary budgets, (e.g. CFSP and Athena), doctrinal corpus, capability development plan (CDP) including the protection of an industrial and technological base and of course, operational engagements. It would also help distinguish between investments and the work necessary for prevention, operational intervention capabilities and work in support of stabilisation.

From a national point of view it would be a useful instrument for rationalisation and coherence to prevent lacuna and duplication at European level. National White Papers might refer to it to justify their choices and bring them in line with common European interests.

The European White Paper might also establish the level of relations and coordination desired with major organisations like the UN, the OSCE, NATO and the AU. It would provide an opportunity to define a new type of transatlantic relationship. It should be updated regularly, ideally each time the European Parliament is renewed.

Conclusion

The CSDP's inefficacy is mainly the responsibility of the States which have not yet taken stock of the dangers caused by the new security environment to their vital interests and which continue to delegate their defence to the USA. As for the citizens they intuitively want to see defence issues addressed at European level[6], they cannot gauge the constraints and are not necessarily prepared to accept them in the present climate of existential doubt about the completion of European integration.

In this climate the drafting of a European White Paper might be a salutary, informative exercise which would help raise awareness of the security challenges that the EU's Member States face and also of the possible solutions available at European level. Its main goal would be to clarify the conditions that would help strengthen the security of all States and their citizens in a concrete manner.

In order not to discourage "good political will" a prior definition of the issues at stake, the goals, the constraints and the protection of national sovereignty is vital to appease fear and to highlight the benefits of drafting a European White Paper. But at the present time in which Europe is clearly disarming and is impotent to respond to armed attacks against its values and interests, there are also opportunities that must not be missed. The view of the defence of a united Europe would place ambitions on a level with what Europe represents, whilst forming a reference framework and a link of coherence and effectiveness with the national defence of all European countries which take part.

If agreement cannot be reached by the 28 on this project it might first be launched by those States that are prepared to participate thereby defining a first approach to permanent structured cooperation.

Annex 1

Review

Budgetary Aspects

In spite of a very slight recent change in trend[7], Member State defence spending is still hugely lacking for it to meet requirements. Whilst it is commonly advocated to devote 2% of the GDP to defence, real figures range from 0.81% to 2.09%, with one country only being over 2% (more than 4% in the USA)[8]. This spending is also ineffective. Hence the military personnel of all 28 EU States together (1.48 million) is close to that of the USA (1.5 million), whilst the sum of the budgets (183 billion €) is 3.23 times below that of our American ally (587 billion €). Capital spending on research, development and the manufacture of equipment is 3.5 times less. Although the EU's population represents around 7% of the world population and its wealth represents 22% of the world's GDP, the share of the EU's military spending only represented 18% of world spending in 2013 (29% in 1996).

Military operations

The successes the EU's military operations cannot be contested: for example ARTEMIS (1,800 personnel) and ATALANTE (1,200, 4 to 7 ships); nor can we contest the benefits of the civilian missions accomplished in an overall approach to crises that have occurred.

Overall these operations have engaged relatively low numbers of personnel, the maximum being EUFOR CHAD CAR in 2008- 2009 (3,700).

Especially and in rare exceptions, decisions taken by the European Council have been too late and force generation too slow. The recent example of EUFOR CAR is typical.

Whilst at the end of 2013 threats of genocide were emerging in Central African Republic action was deemed appropriate on 15th January 2014. The crisis management concept (CMC) was approved and OHQ was designated on 20th January (Larissa in Greece). Operation command was chosen on 10th February.

The decision to launch the operation came on 1st April (three months later.)

The initial operational capability was announced on 30th April and full capacity was reach 15th June i.e. five months later. There were seven force generation conferences between 13th February and 22nd July 2014.

Hence 71 days were required from the approval of the CMC to the decision to launch the operation, whilst 5 days are necessary, in theory, in the battlegroup concept. However the total number of personnel totalled 700. This is unacceptable.

The EU's operations are in fact coalition operations of circumstance with asymptotic limits: lack of leadership, different cultures etc...

Capability and Industrial Aspects

Again in spite of some successes: the A400M; MUSIS satellite imagery programme[9], there are many capability gaps and many surplus capabilities.

Of the annual European defence investment budget of around 50 G€, only 8 to 9 G€ are really invested in armament cooperation programmes, i.e. less than 20%. And this percentage has been stable for more than 10 years whilst the countries of Europe set a goal in November 2007 of 35% within the framework of missions set for the European Defence Agency.

20% is too weak a figure. If the countries of Europe want to spend their increasingly limited defence budgets better and be better able to cover their capability lacuna and strengthen their sovereignty together, their only real option is to spend a greater share together.

The main cooperation failures are primarily due to the lack of programmes, the withdrawal of certain participants and the time taken to launch a programme (this problem affects most cooperation programmes). All of these failures or delays are linked to problems in partners coming to agreement regarding operational requirements, mainly from an industrial point of view (the case with the programmes quoted above) or regarding the timetable (difficulties in aligning capability budgets: these problems were settled for the A400M which was successfully launched because participating countries jointly said what their requirements were and because the European civilian aviation industry (Airbus) had consolidated prior to this.

Experience shows that once launched cooperation programmes do not encounter any more problems than national programmes of equal complexity: the technical problems are the same, equally, delays can happen even though the budgetary or political reasons might be different. However it is clear that the financial advantage expected of cooperation is often severely reduced and even totally cancelled out by short-term demands of fair return[10] on the part of the partners: piecemeal industrial sharing at sub-system level, multiplication production lines, multiple versions of the same system after partner or client disagreements over operational requirements and/or industrial issues.

The completion of the A400M programme launched in 2003 under the auspices of OCCAR, without fair return and a common operational requirement signed by the Chiefs-of-Staff of the Air Forces of eight European countries in 1997, which enjoyed the experience and industrial competences of Airbus in Europe, was not without problems. In spite of the difficulties and cost overruns that followed, the A400M programme is still the best existing example of cooperation in terms of armaments and a major success for Europe, and whose advantages will soon become apparent with the delivery and gradual operational use of the first aircraft.

Annex 2:

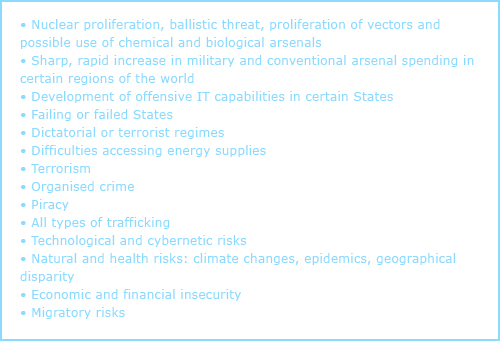

Risks and Threats

National White Papers and more generally the White Papers generated in Europe, as well as the European Security Strategy mainly converge towards the identification of risks and threats. There are conventional threats, i.e. direct or indirect territorial threats to a nation or to Europe, as well as inter-State conflict outside of Europe. Although the direct threat of a European State is deemed unlikely but not impossible, the former Warsaw Pact countries, which are now NATO members, are more sensitive to this possibility, since this type of conflict, according to NATO corresponds to the concept of symmetrical war and also more recently, during events in Ukraine, to hybrid war[11], or to non-linear war according to certain Russian theorists[12]. As for asymmetrical threats these are similar to a certain extent and linked to terrorism, cyber-attacks, organised crime (illegal trafficking, transnational flows, laundering, piracy and banditry) and action against energy flows (making safe resources and supplies of natural resources and raw materials, diversification). The main risks mentioned are climate change, natural or human disasters. More generally the threats identified are often borderless and the global world forces us to provide a national and also European response: "This White Paper must be national, but not just national[13]."

Overall risks and threats are common to all European States and can be summarised in the table below.

Annex 3

Convergence and divergence by zone of interest zone

Zones of interest vary depending on the geographic position and political ambition of each State. Depending on the interest that they represent for the State, they can be the focus of lengthy explanation in the documents we have analysed.

• The USA is considered to be an unfailing ally and all the nations that belong to NATO recall the interest of the transatlantic link. Finland, a non-NATO member but loyal partner stresses that the transatlantic link, via the Alliance, is a major factor of security and stability for Europe.

• Regarding relations with Russia, although every country mentions it, geographic and historical logic means that Poland and Finland devote several pages to it whilst the countries in the south of Europe are more succinct. Whilst aware of a possible threat, France and the UK speak of the need to maintain relations with Russia which means finding common ground that is difficult to achieve in view of the ongoing events. Spain and Italy speak of Russia as being the EU's biggest neighbour with whom it is important to cooperate and which should become a strategic partner. Germany goes as far as referring to a special bilateral relationship, recalling a close if not common history; it recalls the specific role that Russia might play in Europe as a member of the OSCE and that without it, security, stability, integration and prosperity cannot be guaranteed in Europe. Finland, which has a border of over 1000km with Russia sees it as a serious threat to its territorial security. It has observed that Russia's sights affect European security. It speaks at length of the establishment of the Russian armed forces, notably in the Barents Sea, the Kola Peninsula, Saint-Petersburg and Kaliningrad. In spite of Russia's participation in the OSCE, the idea of creating a Eurasian community still has to occur. It does however support the importance of developing relations between the EU and Russia. Poland suggests that Russia wants to the role of a regional power. Poland's security will depend on the evolution of "Russia's relations with the West." It describes two possible scenarios: either Russia will continue to recover its power, ignoring the interests of its neighbours or it will continue to work towards developing joint security. It concludes, in the light of events in Ukraine, that the first scenario remains the most likely. A description of the zones of tension and conflict in the regions of Black and Caspian Seas is provided; it mentions frozen conflicts in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh and Transnistria not forgetting the numerous separatist trends and ethnic tensions.

• From the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf

This vast area which is a priority for France remains "crisis" prone for Germany and Poland: it is the stronghold of international terrorism as well as the development of arms of mass destruction and long range missiles. Italy is on the same wave length but explains its high energy dependency regarding this region. The UK insists on nuclear proliferation. Finland gave great support in 2010 to the proposal to turn the Middle East into a denuclearised zone, free of all arms of mass destruction. It believes that this region, like Africa is of strategic importance to Europe. Finally Spain focuses mainly on the Mediterranean and its rim.

• Africa

Africa, or more precisely North Africa, is deemed by most European countries (except for Poland) to be of capital importance to Europe. A zone of priority interest for France, the latter believes, like some other countries that we have to help Africans take ownership of their own security. Italy again mentions its energy dependency and the UK focuses on the terrorist threat. Finland is investing its mediation capabilities via the EU in regional organisations like the African Union.

• Other regions

The stakes represented by the Arctic are mainly spoken of by Finland and Poland. This region is of strategic priority to Finland which hopes to maintain stability there in order to guarantee its own security. France also briefly mentions the strategic impact caused by global warming in the Arctic.

Security and maritime access in Asia Pacific are deemed a priority by France which is a permanent member of the UNCMAC (United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission, Korea) and a regional power. Germany speaks of the importance of political/strategic dialogue with key States in the region stressing the rapidity with which military arsenal are increasing. The UK stresses the importance of bilateral relations that it has notably developed with India and China. It mentions the support it provides to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Spain only mentions the Pacific via its privileged relations with Latin America, a region of major importance for its political and strategic interests. It is trying to acquire observer status within the Pacific Alliance that rallies Chile, Peru, Colombia and Mexico.

Other references to Latin America mainly involve the EU and its Member States' action as part of the fight to counter drug trafficking.

Annex 4

Strengthening EDTIB via pooling, specialisation and cooperation

We can take on board and use existing strengths and competences in one or several States in response to collective requirements without creating new competing capabilities, we can even relinquish some that are superfluous and uncompetitive.

Pooling and sharing

To guarantee the success of international cooperation, whether this is bilateral or multilateral, a certain number of criteria have to be met:

- Realistic harmonisation of requirements from an operational and technical point of view and also from the point of view of timing, to reach as common a definition as possible, - which can be consolidated after a feasibility study - and to retain a joint configuration long term;

- From an industrial point of view - better use of existing partners' competences, which means giving up the idea of "fair return", which can only be negative in terms of quality, costs and timing, to the benefit of implementing a globally balanced long term concept and including a series of programmes;

- Introduction of improved programme management structures and methods both from an industrial and State point of view.

The principle of fair return programme by programme has to be proscribed. Instead of privileging the best existing competences and capabilities, concern over acquiring new competences has often led to duplication which leads to redundant, dispersed capabilities. Sharing development and production activities should now be organised according to a strict principle of industrial efficacy and economic performance.

Efforts to pool trial and experimentation tools which has not led to any conclusive results to date (the trend is rather for certain countries to acquire new tools whilst their partners already have them), must be continued. Like France and the UK over the past few years, the EU has to have a collective awareness of the importance of continuing investment in research and development constantly in all sectors which contribute to the building of a common coherent defence tool.

From an industrial point of view a certain amount of consolidation will be inevitable in the defence sector since European States will not be able to afford the great number of duplications and surplus capabilities long term (in view of the European market) that exist in some sectors (naval, land armament sectors notably). This consolidation, based on the best competences, would provide European industry with greater competitive edge over world competition.

The progress achieved by MBDA in France and the UK in the missile industry which aims to pool industrial research and development capabilities in both countries is an illustration of the feasibility and pertinence of this approach between partners who are prepared to commit to a path of freely chosen interdependency.

The goal must be to form the base of an economically viable European defence industry that relies on specialised, complementary poles of excellence the distribution of which takes on board in a balanced manner the reality of existing competences and investments that have already been made.

However we should be aware that restructuring like this must above all be based on industrial initiatives and supported by programmes.

Annex 5:

Suggestions for the content of a White Paper on the Security of Europe

1. Introduction

The World Situation

Major Upheaval and New Challenges

2. Europe and Threats: a Weakened Environment

Collapse and Developments

Ranking of Threats (types and location)

Identification of solidarity between EU members per type of threat

3. Europe: its roots, values and specific model

Economic, social, democracy, Human Rights, environment, neighbourhood, resilience

4. Europe's Ambitions: Strategic Security Goals

Ambition

Choice of Power (coercive or not)

Strategic Autonomy, European Integration and Subsidiarity (respect of national prerogatives), coordinated energy policy, neighbourhood security, enlargement, partnership prevention, Human Rights, relations with organisations,

Goals

Citizen Protection

Protection of wealth and European interests (infrastructures, know-how, research, technology, energy sources,)

Protection of European territory and the transatlantic area

Building security in the European neighbourhood, notably on the Eastern and Southern flanks

Peace participation in the world

Legitimise action

Increasing the cost effectiveness of defence for each State of the Union

5. Established European Mechanisms

Internal Security

CFSP

Progress of the Lisbon Treaty

6. Action to take

New Integrated Policy (internal and external)

Men, women, European citizens. The European flag

Implementation of the global approach: coherence of the Union's external policy

Legitimacy of action: EU-UN relations

Crisis management: engagement scenarios

Complementarity with NATO and transatlantic relations

Neighbourhood Policy and Partnership

Coordination with regional organisations (AU, Arab League, ASEAN)

Development of civilian and military capabilities (per area of capability)

EDTIB Coherence

[1] Article 1 bis of the Lisbon Treaty: "The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail."

[2]Excerpt from the Synopia report on the European Union's external action (September 2014)

[3] As it was done for Sahel and the Horn of Africa

[4] See Correlates of War, Human Security Report, SIPRI, PRIO, Global Peace Index

[5] European Council "shall identify the Union's strategic interests, determine the objectives of and define general guidelines for the common foreign and security policy, including for matters with defence implications."

[6] 76% of Europeans say they support a Common Security and Defence Policy (Eurobarometer 82 Autumn 2014)

[7] For example Poland increased its defence budget by 13% in 2014 (Le Monde International 13th April 2015: http://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2015/04/13/augmentation-des-depenses-militaires-en-raison-de-la-crise-ukrainienne_4614634_3210.html

[8] Source Eurodéfense: comparison of defence efforts (2013 data)

[9] France has successfully specialised in optical imagery whilst Germany and Italy (separately) have invested in radar imagery.

[10]The fair return will be part of the common good from which everyone will benefit

[11] NATO review magazine July 2014: "Hybrid war? Hybrid response? And how can international security organisations like NATO adapt to these attacks?"

[12] JD Merchet, L'Opinion 1st September 2014

[13] Michel Barnier 20th August 2013

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :