supplement

Olivier Rozenberg

-

Available versions :

EN

Olivier Rozenberg

At regular intervals elections show that as far as its support to Europe is concerned there is "something rotten" in the Republic of France. In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty was approved by narrow majority. Nearly one French MEP in two elected in 1999 said they were against the European treaties. In the 2005 referendum the French "No", put paid to the European Constitution. And then in 2014, the Front National, a far right anti-euro party won the European election, both in terms of votes and seats. In view of the important historic role played by France in the founding of European integration in the 1950's[1], this series of events is surprising. The growing number of crises and tension over the last twenty years suggests that these phenomena are not just the expression of the rejection of the executive or concern on the part of the opinion about the country's economic difficulties. It is our theory that there is something deeper and more directly European in this development and is linked to Europe's national "narrative". The French elites have built a public narrative to the justification of European integration that we might summarise with the formula "Powerful Europe". After explaining what the narrative is, this paper assesses its progressive erosion before analysing the difficulties in finding a new one to replace it.

1. The ambiguous narrative of "Powerful Europe"

The goal of sustainable peace in Europe, and notably regarding Germany, is an old and central element of the national discourse to justify European integration. However this pacifist credo often overlaps with an argument that seeks rather more national power and prestige. "The euro makes us strong": this slogan chosen by the French government to sell the euro to public opinion in 1990 is a good insight into the narrative of powerful Europe. Indeed it asserts that European integration is a guarantee of power, strength and efficiency for France[2]. The extra power provided by Europe does not lie as much in the large scale savings offered by integration but in the geographical dimension of the European zone. The logic behind this is basically more geopolitical and economic. During the Cold War the European Economic Community was seen as an entity that could stand up to the USSR and to a lesser degree, the USA. Since the 1990's the European Union is presented as protection in context of globalisation against competition on the part of countries with low labour costs and the multinationals.

The idea of powerful Europe originates in the lucid observation of France's declining international influence. Military defeat in 1940, a critical post-war situation and decolonisation: all of this contributed to a realisation on the part of the political and administrative elites that the country could no longer pretend to influence the course of world affairs alone. From this point of view Europe stands as both relinquishment and utopia: relinquishment of a certain Messianic claim by the nation born of the French Revolution but also utopia with the idea of rescaling this claim to a European level. The implicit idea of powerful Europe is that what France can no longer do alone in the world, it will do in Europe and by Europe. Hence there is innate ambiguity in the narrative of powerful Europe. European integration and the transfer of sovereignty that this implies are accepted if, and only if, they help towards restoring or maintaining France's power. At base Europe is at the service of a national cause.

There are many examples of the ambiguity of France's pro-European stance from the very beginning. In a Eurosceptic version we might note the ambivalence of De Gaulle's Presidency (1958-1969) who accepted the implementation of the Rome treaties whilst simultaneously defending each State's absolute right to assert its vital interests during "the empty chair crisis". In a more Europhile version we note that President Mitterrand (1981-1995), who, as of 1983 substituted socialist radicalism for the project of an integrated Europe, nevertheless defended a clearly intergovernmental vision of it on an institutional level. In Maastricht he imposed a European project founded on pillars which preserved common diplomacy from any form of communitarisation. Finally in a pragmatic version we note President Chirac (1995-2007) who tried to qualify France for the euro before withdrawing from the constraints of the Stability and Growth Pact[3]. On a domestic level we also find evidence of the ambiguity of the narrative of powerful Europe in the reticence shown by a series of institutions in accepting the implications of the treaties on law and national public action[4]. It took until 1989 for the State Council to accept the full primacy of European law. Governments and MPs agreed until 2005 not to constitutionalise the general rule of sharing or the transfer of sovereignty, preferring to acquiesce on a case-by-case basis. On various occasions between 1990 and 2000 MPs and senators approved texts contrary to European law, starting with the laws governing bird hunting periods which contravened a 1979 directive.

2. The slow erosion of the European narrative in France

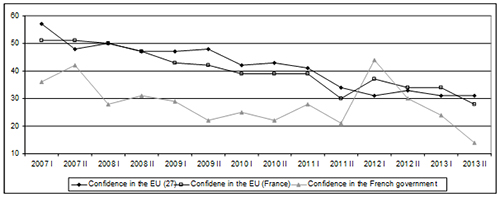

Hence Europe was legitimised on a domestic level as a condition for the protection of national power. This narrative has not yet disappeared. We note that the Presidency of the Council in 2008 was prepared, exercised and then celebrated by President Sarkozy as a vital stake for the country's glory, as well as his own[5]. The results of the referenda just like the European elections mentioned in our introduction indicate however that the strength of this narrative has been on the decline for more than two decades. The polls that measure the European Union's popularity confirm this relative decline: whilst one French man in 20 believed that belonging to the EEC was a bad thing in 1973, the ratio was one in four in 2010[6]. The economic crisis that began in 2008 accentuated the population's euro scepticism. In this regard graph 1 illustrates the rise in mistrust in France (+23 points in 7 years) but also enables us to relativize the degree of this at the same time. This is because on the one hand the trend is the same amongst all national public opinions and on the other, mistrust regarding the national executive is greater, apart from a fleeting moment, after the elections.

Graph 1. Developments in confidence in the EU and the French government (2007-2013)

Source : Eurobarometer

Source : Eurobarometer

In spite of this it seems that euro scepticism is rising in French society. Powerful Europe is finding it increasingly difficult in persuading people to love Europe. Political parties and their leaders also take up the different criticism made of European integration and the way it functions. Criticism is expected from the extremes given that for a long time it has been an effective vector of differentiation regarding the government parties. The relative continuity of the European policy on the part of governments both on the left and the right is highlighted by the Front National (FN) as well as the communist party as a sign of collusion. Europe is particularly useful to the FN and its Chair, Marine Le Pen. Committed to a normalisation strategy since 2011, this party is trying to erase the most controversial aspects of its discourse on identity issues. At the risk of becoming banal Europe, allows the assertion of acceptable radicalism, since it is racism-free. But criticism of Europe in this case is far from anecdotal since electoral polls show that it was one of the first reasons behind the Le Pen vote in 2012[7]. We should note however that the normalisation strategy reached its limit in the European Parliament since Marine Le Pen did not manage to rally MEPs from enough Member States to create a political group. In addition to the extreme political parties there are also the "issue parties" specifically focusing on European issues. This was the case of various parties that were somewhat successful in the 1990's and 2000's before they dropped back into marginality: the sovereignists mainly born of the right on the one hand, and a rural party initially formed to defend hunting rights on the other.

If the extremes are united in the criticism of Europe, it regularly divides government parties both on the left and the right. The divisions on the right in the 1990's between the pro-Maastricht and the sovereignists were succeeded by those on the left, between the pro-European Constitutionalists and the anti-Liberals in the 2000's. These divisions show that in France the camp which supports Europe cannot be reduced to one or the other political groups. The right is divided between its Gaullist filiation, sensitive to national independence, and a liberal group which identified so much with Europe that the cause might have justified the existence of a specific partisan unit. Part of the government left is quick to challenge the Union's liberal logic. Moreover various ideological tensions are a regular part of the personal political game. Since Jacques Chirac's attack on President Giscard d'Estaing in 1979 to Claude Bartolone, leader of the National Assembly, asking Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault to "confront" Germany in 2013, we see that challenges to the European treaties, alliances or policies are a strategic choice by the challengers in a bid to claim leadership of their camp. This tactic is dangerous since it can damage the challenger's image as a statesman. It is however undertaken consistently, since enables the challenger to criticise the leader of the camp for his inaptitude in defending national interests and also for him to distinguish himself from his adversary. In addition to this the careers of some MPs critical of European integration lead us to relativize the risk being run. On the right François Fillon, anti-Maastricht in 1992, became Prime Minister in 2007. On the left, Laurent Fabius, anti-European Constitution herald in 2005, became Foreign Minister in 2012.

3. The growing inadequacy of powerful Europe

For the observer the striking feature of the European debate in France is not so much the cyclical emergence of critical discourse of integration which, after all, already marked French public debate profoundly in the 1950's with joint, virulent criticism on the part of the communists and Gaullists. Undoubtedly the most remarkable thing since François Mitterrand has been the difficulty for leaders who support the treaties to assume and justify their position in the public debate. An analysis of the programmes and discourses of the government parties reveals their lukewarm support of integration in the way it functions and sometimes in its principle. On the right it is readily pointed out that the European Union has to stop its claim to regulation and harmonisation. On the left the Socialist Party (PS) has called for a social re-orientation of European integration for a long time. During the 2012 presidential election campaign the candidates' challenge of the common policies took a new turn in terms of its scope and resonance[8]. Outgoing President Nicolas Sarkozy, conditioned France remaining in the Schengen Area to an in depth review of the system. His socialist rival, François Hollande announced that he would not sign the Fiscal Compact as it stood - but which in the end he did resolve to do. In addition to the assumed, cultural euroscepticism of the extremes there is also a kind of "soft" euroscepticism on the part of the leaders of the government parties.

This type of difficulty in publicly assuming support to European integration undoubtedly lies in the need to rally the extremes in each camp. It also illustrates the erosion of powerful Europe as a major national narrative to justify integration[9]. This decline is firstly rooted in the fact that the different Presidents, particularly Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and François Mitterrand used the European credo to the full to justify their policy. Valéry Giscard d'Estaing believed that the European narrative helped to distinguish himself adroitly from the Gaullist presidencies. Mitterrand felt that it offered him a substitute utopia to the failure of neo-Marxist policies. Moreover, from a negative point of view, successive government leaders have blamed "Brussels" for unpopular policies in the ilk of Jacques Chirac who relinquished his campaign promises as soon as he was elected in 1995 on the grounds of preparation work necessary for the euro. Powerful Europe has therefore suffered because it was used too much as a positive and sometimes a negative reference. Beyond that this credo seems to be ill adapted for two reasons.

Powerful Europe is firstly a functional mode of legitimisation. In this light European integration is justified because it can provide extra power and therefore produce results. Clearly this type of justification is problematic when results are not produced, which has been the case both from an economic and geopolitical point of view. On an economic level France's mediocre performance and also the difficulty in overcoming social dumping or taxing financial speculation relativizes the idea that "in unity there is strength". On a geopolitical level the Member States' division over various strategic issues, starting with the war in Iraq in 2003, and France's isolation in terms of its interventions in Africa, also sap the idea of a power-boosting Europe. Support to Europe suffers because it has not produced the expected results: this may seem evident. However it is important to note that Europe is all the more lacking in results, since in France and also in other countries, like the UK, it was justified with a functional and even practical purpose. National narratives that have focused on the idea of national rehabilitation, the modernisation of society and even on Westernization have undoubtedly suffered these problems to a lesser degree.

Secondly powerful Europe is also an ambiguous mode of justification in that it places the defence of France's grandeur at its centre. In this instance, in the French mind, European integration is not a victim of its failures but of its successes. In spite of the weaknesses of the structure, European integration has deepened since the 1980's, as illustrated by the body of European norms that have been adopted, the generalisation of the qualified majority decision making process and also the Europeanisation - via the diffusion effect - of sectors that are not normally covered by integration (social protection, education system, defence etc ...). The Europeanisation of public action is obvious. It is not necessarily opposite to the idea of a powerful Europe to the benefit of France. Hence the national political elites largely echoed the forecast made by Jacques Delors - which was also false - that 80% of economic and social legislation would come from Europe. However when the deepening of integration prompts the formulation of orders by the European institutions, even by political leaders of other Member States, the lack of realism of the French myth of Europe then emerges. For several years now, whether it has been a question of banning or re-instating State aid, the control of company mergers or the end of State monopolies in various public services, there have been many examples of European decisions which seem to override national authorities. For the first time in 2005 France was fined for not implementing European law. Above all, because of the economic, financial and monetary crisis that began in 2009, the European Union adopted a theoretically stricter control of budgetary deficits. European constraint therefore became a key element in national public debate. It was used by the opposition in the case it made against the socialist majority, in office since 2012, for its economic incompetence and also by the Presidency of the Republic, which did not fail to point to Brussels' involvement in some of its major decisions, from raising taxes to changing its Prime Minister.

From a powerful Europe capable of restoring France's lost prestige, we have moved imperceptibly on to a Europe of sanctions that justifies the implementation of painful domestic reform. The enlargement of the European Union on the one hand and the economic, then political domination of Germany on the other, have completed the destruction of any credibility in a French Europe. The enlargement of 2004, which was not debated much in parliament or the media, was perceived by both political and administrative elites as a relinquishment of the deepening of integration. Nostalgia for the Europe of 12 emerged indirectly in the idea of a Union for the Mediterranean (UpM) launched by Nicolas Sarkozy under the French Presidency of the Council in 2008. The initial version of the project did not include Germany thus returned to its Eastern sphere of influence, whilst France turned its attention to the leadership of the Southern. However different the context, the fantasy of a union of the "Club Med" countries in the face of austere Germany, which has been regularly mentioned under the presidency of François Hollande, also reflects the idea of rescaling regional integration, in which France might recover its lost prestige.

4. The problematic reworking of France's European Narrative

The erosion of the powerful Europe narrative lies then, in part, in the structure of the narrative itself. In this light French political leaders seem to lack imagination in designing a replacement. We note for example that they struggle to respond to the rhetoric and projects drawn up by their German ally, whether this involves the 1994 Schäuble-Lamers project or the speech given by Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer, in 2000 at the Humboldt University. From time to time French Presidents are called to speak about Europe but these declarations, which sometimes indicate that they have been reluctantly drawn up after several weeks of campaigning by the newspaper Le Monde as it criticises the Elysée's silence, are often consensual, if not flat, and rarely inspiring, not to say vain. Hence in May 2013 during a press conference François Hollande laid out his European project focusing on four priorities: economic government of the euro zone with a president at its head; a European plan against unemployment; the enhancement of Energy Europe and the introduction of a common investment strategy. We note that these measures are a copy of the ideas put forward a long time ago by the national authorities, notably regarding economic government. The latter priority put forward during the speech has been contradicted since by France's difficulty in respecting its budgetary commitments. Some months later, whilst the Commission was drawing up specific recommendations for reform, affecting both the labour market and retirement pensions, the French President made a public show of his disagreement, refusing the Commission's right to interfere in his country's domestic affairs. In fact this stance seemed like a refusal since the reforms that have been introduced since are close to those promoted by Brussels.

Beyond the ambiguities of the government's economic project this speech is striking, since like those delivered by Nicolas Sarkozy previously, there is no "grand design" from a European point of view. It is as if the increase in real priorities were obscuring the difficulty in rebuilding a French narrative of Europe. The reason for this lies in the national political culture on the one hand and in the French political system on the other.

It is always awkward to speak of political culture since preconceptions can replace empirical analysis. In spite of the pitfalls of culturalism it seems that the norms shared by the French political and administrative elites are increasingly distanced from the Europe as it is now developing from two points of view: reticence over free market conditions on the one hand and the reverence of the idea of political voluntarism on the other. On the first point comparative opinion polls show that the French population - including people qualified with diplomas from higher education - have been, with the Mediterranean countries, those who have criticised the principles of economic liberalism the most severely[10]. Although ten years ago the same polls placed the French amongst the Europhiles, circumspection of the free market is a significant limit in terms of the relationship with Europe. Hence, Christian Lequesne has illustrated how reticence about enlargement was not just linked to fear of a loss of France's centrality[11]. By repeating that Europe should not just be a big market political leaders at the same time basically implied their lack of enthusiasm for the single market.

Secondly French political culture idealises the concept of political voluntarism i.e. the ability to transform society via politics. This characteristic, pointed to by many authors, is understood in a long term perspective, which goes even further back than the French Revolution, to the constitution of the French nation based on the State. Oriented towards the institutions, the primacy of political voluntarism tends to foster personalisation and centralisation over collective, multi-level governance. With this we understand the proximity of the diagnoses and solutions put forward by leaders on both the left and right: Europe is missing a leader who will impress his/her will upon it. The European Council was created on a French initiative. The Delors era is revered with nostalgia. The permanence of the presidency of the European Council, established by the Lisbon Treaty was welcomed, whilst other legitimisation strategies were regarded with more circumspection (parliamentarisation, transparency, constitutionalisation, better regulation, etc.)[12]. The solution of a "political Europe" is so regularly put forward that the idea has become polymorphous and even meaningless.

We are not trying to decide about the merits of the market economy or of political voluntarism but to point out that the values that hold French leaders together tend to distance them from Europe as it is developing now and that it is hard for them to form a discourse of justification. From this point of view the politicians and executive civil servants resemble the French intellectuals studied by Justine Lacroix, who accuse Europe of lacking body, i.e. a real political community and a leader - in other words coherent political thinking[13]. As Ms Lacroix does this she analyses how these intellectuals succeed in defining an imaginary European doxa which views the past through the prism of Western guilt and the nation as a warmonger.

Another set of explanations regarding the difficulty in renewing the French narrative of European integration, involves the V Republic. Presidential centralism offers a certain degree of efficiency in the definition and pursuit of major national priorities on a European level. However it damages the design of a coherent vision in two ways. Firstly the two-round presidential election obliges the candidates from the two parties seeking victory to draft a synthetic vision of Europe that can win over, both Europhiles and Eurosceptics within each camp. The catch-all nature of the major government parties is certainly a general fact of modern democracies. It is however clearly distinct in France regarding Europe given the conjunction between the method used to elect the head of the executive [14] and the division within each electorate over this issue. The positions of the Socialist Party candidates (PS) and those of the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) subtly resemble balanced motions of congress. In 2007 in the wake of the failure of the European Constitution candidate Sarkozy announced that he would negotiate a new treaty and would not put it referendum; he also place great emphasis on his rejection of Turkey's membership[15]. In 2012, candidate Hollande accompanied his intention to renegotiate the fiscal pact with an ambitious European agenda, with the creation of euro-bonds, a European ratings agency, a directive on public services - all supported by a European budget "at the service of major projects for the future."[16] Electoral analysis indicate that in the first round he was supported to proportionately the same degree by voters who approved or rejected the constitutional treaty in 2005[17]. Therefore Hollande's European summary was key to his victory.

Another detail in this institutional explanation is that the President's supremacy is such in terms of how France's European policy is to be undertaken that he does not have to respect his electoral programme[18]. François Hollande's triumph in 2012 is a striking example of this. The promise to renegotiate the fiscal treaty, which helped politically towards the socialist candidate's victory, was never really followed up. The President accepted the treaty in exchange for symbolic counterweights which, in hindsight, now appear to be quite marginal. In spite of some mood swings the ratification of the treaty in the autumn of 2012 went quite smoothly[19]. The important thing here is not whether the French President was able to act otherwise, but to note that since the parliamentary phase is not a constraint for the President the candidate could define a programme which he knew was not really binding. Disconnection of this nature between electoral and public politics does not foster - from a European and other points of view - the establishment of coherent programmes and doctrines by the government parties. The candidate's vision of Europe is very often drawn up in a hurry, just before the campaign meeting devoted Europe. The French elites' difficulty in thinking "Europe" can be explained in part - and only in part - by the superficiality of the parties' programming work - which is mostly encouraged by the primacy of the President over the political system.

Conclusion

This paper has tried to understand why French political leaders have so much difficulty in finding a European integration narrative. The old narrative of powerful Europe has gradually declined with the relegation of France to second place without there being another doctrine to take its place. This is due to both the elites' political culture as well as the institutions of the V Republic. The most remarkable thing in this is that this doctrinal breakdown has not really affected France's implementation of European policy. To a certain extent the country has the means to continue a strategy that is no longer believed or defended in the public sphere. The President's institutional capacity and the permanence of a pro-European senior civil service has been enough to palliate this for the time being. However we can see that the difficulty experienced by France in finding its place in Europe regularly means that the executive defended prestige rather than national interest, in the ilk of Jacques Chirac in 2000, as he accepted the end of parity between Germany and France in the European Parliament so that he defend the Council better.

Is the gulf between French governments' European choice and the public sphere, which is dominated by the criticism of Europe, endurable long term? The time taken for the government parties to develop their programmes, sometimes proposing to review the free-movement of people and then the ban on State aid or advocating the re-nationalisation of environmental policies, gives us grounds to doubt it. Gramsci's lesson, outdated of course, does retain some of its pertinence however: the battle of ideas is lost at a cost. With hindsight we note that the Maastricht Treaty was anticipated by Mitterrand as he turned Europe into the horizon for both his policy and nation. In the light of this the soft euroscepticism of the government parties seems to be paving the way for a critical development in France's European policy[20].

[1] Cornelia Woll and Richard Balme France, "Between Integration and National Sovereignty", in Simon Bulmer et Christian Lequesne (dir.) The Member States of the European Union, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005, 1ère ed., pp. 97-118.

[2] Gérard Bossuat, La France et la construction de l'unité européenne, de 1919 à nos jours, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012.

[3] Hussein Kassim, "France and the European Union under the Chirac Presidency", in Alistair Cole, Patrick Le Galès and Jonah Levy (dir.) Developments in French Politics, New York, Palgrave, 4ème ed., 2008, pp. 258-276.

[4] Olivier Rozenberg, "France: Genuine Europeanisation or Monnet for Nothing?" in Simon Bulmer et Christian Lequesne (dir.) The Member States of the European Union, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, 2de ed., pp. 57-84.

[5] Helen Drake, "France and the European Union", in Alistair Cole, Sophie Meunier, Vincent Tiberj (dir.), Developments in French Politics 5, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 218-232.

[6] Sources: Eurobarometer.

[7] Nona Mayer, "From Jean-Marie to Marine Le Pen: Electoral Change on the Far Right ", Parliamentary Affairs, 1/2013,pp. 160-178.

[8] Renaud Dehousse, Angela Tacea, "The French 2012 Presidential Election. A Europeanised Contest", Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po, 02/2012.

[9] Vivien A. Schmidt , "Trapped by their ideas : French élites' discourses of European integration and globalization", Journal of European Public Policy, 7/2007, pp. 992-1009.

[10] Luc Rouban, "La France en Europe", in Pascal Perrineau and Luc Rouban (dir.) La politique en France et en Europe, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2007, pp. 409-424.

[11] Christian Lequesne, La France dans la nouvelle Europe, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2008.

[12] Helen Drake, "France in Europe, Europe in France: The Politics of Exceptionalism and their Limits", in Tony Chafer and Emmanuel God (dir.) The End of the French Exception? Decline and Revival of the 'French Model', Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2010, pp. 187-202.

[13] Justine Lacroix , "Une Europe sans corps ni tête. La pensée française après le 29 mai", in Justine Lacroix and Ramona Coman, Ramona (dir.) Les résistances à l'Europe, Bruxelles, by ULB, 2007, pp. 155-165.

[14] The general elections and/or a round that leads each political party to assert its specific nature and differences, going as far as adopting a coalition agreement before or after the elections.

[15] Renaud Dehousse, "Nicolas Sarkozy l'Européen", in Jacques de Maillard and Yves Surel (dir.) Les politiques publiques sous Sarkozy, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2012, pp. 153–188.

[16] See François Hollande's project, "Mes soixante engagements pour la France", January 2012. http://www.parti-socialiste.fr/articles/les-60-engagements-pour-la-france-le-projet-de-francois-hollande.

[17] Jérôme Jaffré, "La victoire étroite de François Hollande" in Pascal Perrineau (dir.) Le vote normal. Les élections présidentielle et législatives d'avril-mai-juin 2012, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, pp. 133-160.

[18] The political supremacy of the President is gauged against the size of his parliamentary majority. But since 2002 partly because of the transfer over from a seven to a five year presidential mandate the three successive Presidents have all had a majority parliamentary majority in the National Assembly.

[19] Anja Thomas and Angela Tacea, "The French Parliament and the EU - 'shadow control' through the government majority", in Claudia Hefftler, Christine Neuhold, Olivier Rozenberg and Julie Smith (dir.) Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union, Basingstoke to be published.

[20] I thank Eric Thiers for re-reading the text.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :