Democracy and citizenship

Gaël Brustier,

Corinne Deloy,

Fabien Escalona

-

Available versions :

EN

Gaël Brustier

Corinne Deloy

Fabien Escalona

Firstly Corinne Deloy addresses the internal dynamics of the right families (Liberals and Christian-democrats). Historically the latter have worked towards European integration with the social democratic family covered by Fabien Escalona, who then addresses the two other left-wing families that sit in Parliament (the Greens and the far left), which are more recent and/or present greater opposition to the Union. These two trends are also confirmed to different degrees within the far and extreme right parties, covered by Gaël Brustier.

From this overview a contrasted picture emerges in which there is a mix of remarkable developments in the European political arena and a relative decline in influence of the major traditional government parties on the one hand and a certain kind of continuity in terms of right/left balance and especially control over Parliament by the "central bloc" of Christian Democrats, Liberals and Social Democrats on the other. In the context of a Europe in crisis everything points towards a growing disaffection on the part of European citizens regarding their own national political systems and that of the Union, without the functioning of the latter being greatly affected however.

Another lesson to be drawn from this analysis is the constitution of the groups. Their internal heterogeneity seems to have grown, which implies a weak match between their "borders" and those of political families they are supposed to be representing. Indeed these are based on a socio-historical background and an ideological heritage that not all of the present members of the various groups necessarily share. This phenomenon can be linked to an inflow of MEPs from new parties, which the existing groups have had to recruit in order to guarantee their own coninued existence, ie increased influence in the Parliament.

Introduction

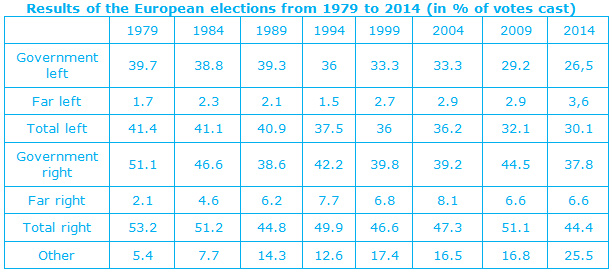

Stability is the first impression we have of the new Assembly that resulted after the election on 22nd-25th May 2014. The government right won 37.8% of the vote on average in Europe, a decrease of 6.7 points in comparison with the elections in June 2009. The far right won 6.6% of the vote - a result that is on a par with that of five years ago, which masks major disparities from one country to another. All of the right together won 44.4% of the vote (- 6.7 points) whilst the left - already weakened in 2009 continued to decline. In 2014 with 30.1% of the vote, they achieved their lowest result ever in a European election. The far left gained one point and the government left declined by 2.7 points. The Member States governed by the left (Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, France, Lithuania, Slovenia) were more affected by the sanction vote than those governed by the right.

The government right won in 2/3 of the Member States, winning the absolute majority in four (Poland, 70.8%, Latvia, 68% ; Luxembourg, 52.3% and Hungary, 51.4%). The three main right-wing groups in the European Parliament have lost ground however after the 2014 elections and two pro-European groups - the European People's Party (EPP) and the Alliance of Democrats and Liberals for Europe (ALDE) - won 288 seats - a figure very much below the parliament majority (376). Although the EPP retained its place as the leading European party with 29.4% of the vote and 221 MEPs it lost 53 seats in comparison with 2009.

In spite of this decline the "Socialist and Democrats" (S&D) group failed to become the leading political force in the Strasbourg Assembly. On the other hand the far right and left gained or stood their ground, likewise many parties that do not fit either into the left or right. The 2014 election seems therefore to be an illustration of a more general trend in the decline of the government parties[1], and in spite of the difficulties, the right continues to dominate the left structurally from a European point of view.

After the election nine new MEPs do not belong to any political group whilst 43 are non-attached. The number of seats in parliament has been reduced (by 15) in comparison with the outgoing Assembly in virtue of the Lisbon Treaty.

1. The European Right

1.1. The European People's Party

Founded in 1976 the EPP has been the leading group in the Parliament since 1999. It also holds the majority within the European Council which comprises the 28 Heads of State and government of the Member States (12 representatives). It has 9 representatives in the outgoing Commission where, apart from the Presidency, it holds major portfolio like the Internal Market, Services, Financial Programming and the Budget and also Energy.

The EPP is a federation of Christian democratic parties. In spite of the risk of weakening the party's identity, over time and the successive enlargements it has welcomed into its fold some parties that have no links to the Christian democratic tradition. For the German Christian Democratic Union (CDU) which has dominated the party, coherence was not as important as the number of parties that the latter could take in, the goal being to make the EPP the leading party in the European Parliament.

Attitude to European integration and the campaign

Hence the EPP has done a great deal towards enlargement seeing in the arrival within its fold of right and centre-right parties from Central and Eastern Europe an opportunity to gather strength to the detriment of its socialist rival[2]. Over time tension between those in support of integration and those supporting sovereignty within the EPP has become increasingly acute.

A centre-right party that supports a "social market economy" (which conjugates competitiveness and free enterprise with the principles of social justice), the EPP rallies 72 pro-European parties in the 28 Member States and from 12 other countries. The parliamentary group demonstrates high internal cohesion (92.6%)[3] and its real power within the hemicycle is superior (by 2.1 points) to its nominal power[4].

In 2014 it campaigned using its results as head of the Union as a support. The EPP stands as a "party of responsible government" which has "protected the euro zone and laid the foundations for economic recovery". It highlights the need to reform the financial markets; the continuation of aid to businesses; investment in research and development; the unification of the digital market and the creation of a European Energy Union. The EPP also supports the introduction of minimum social norms. It hopes to strengthen cooperation between Member States notably regarding the management of the Union's borders and to develop a strong transatlantic trade partnership[5].

The former Prime Minister of Luxembourg (1995-2013), Jean-Claude Juncker was appointed as the EPP's candidate to head the European Commission during the Dublin congress of 6-7th March last. A symbol of European budgetary consolidation, the former Eurogroup President (2005-2013), who is against all types of tax on financial transactions and extremely reticent about fiscal harmonisation, advocates the continued consolidation of public finance, which in his opinion, is vital to regain investor confidence and in fine to revive growth.

The Results

The EPP came out ahead in the European elections in 14 of the 28 Member States. Except for in Romania and Slovakia, the right made a landslide victory in the former communist countries. The recent events in Ukraine seem to have strengthened the government parties, who are mainly on the right in this part of Europe where Moscow's threat is felt more strongly than elsewhere. This is particularly evident in Latvia and Lithuania. Moreover in the former communist countries the right-wing has often positioned itself in an authoritarian and even populist niche (Hungary, Bulgaria), and has managed to occupy the political space of more extremist parties, even to the point of driving the latter out.

Although the two main German parties which share power in Berlin dominated the election and gained ground, the CDU easily drew ahead of the SPD (by 8 points) with 35.3% of the vote. The German right emerged victorious from the election in spite of the continued collapse of the FDP and the abolition of the vital 3% threshold in order to gain representation. This last measure enabled the entry of "small" parties into the Strasbourg Assembly and caused the loss of between 5 and 7 seats for the CDU.

In Austria, the ÖVP also came out ahead of Chancellor Walter Faymann's SPÖ. In Finland, the Kokoomus, KOK, dominated the election. In Spain Mariano Rajoy's People's Party (PP) won with 26% of the vote. In spite of a decline of 16 points it managed to come out ahead of the PSOE. In Latvia, Unity (V), the Prime Minister Laimdota Straujuima's party, clearly dominated the elections winning 46% of the vote and taking four seats, with the nationalists of TB/LNNK coming 2nd with 14% of the vote. The situation was the same in Hungary where Prime Minister Viktor Orban's FIDESZ-MPP won the absolute majority less than two months after its victory in the general elections.

Europe's leading party the EPP did however suffer two defeats. In Italy Angelino Alfano, the leader of the right leaning New Centre suffered defeat (4.3%) and Forza Italia won 16.8% of the vote, in other words, half of its 2009 result. The party now only has 14 seats after being weakened by the conviction of Silvio Berlusconi. Easily out-distanced by the President of the Council Matteo Renzi's party, the Italian right lost 17 EPP seats in all. In France the UMP was beaten by the FN and lost one third of its European representatives. Without a leader, programme and vision the French right was almost inaudible during the campaign that was dominated by Marine Le Pen whose result reveals the French population's mistrust of all of the political class.

1.2. The Alliance of Democrats and Liberals for Europe (ALDE)

Since 2004 the ALDE has comprised the Alliance of Democrats and Liberals for Europe (ALDE) and the European Democratic Party. It rallies 58 parties from 22 Member States and 13 other European countries. The Stuttgart Declaration of 1976 is the group's founding charter. It supports "more Europe": development of integration, the defence of Human Rights and freedom, notably the freedom of movement within the Union. In its opinion the development of economic growth and the reduction of inequalities are to be achieved by greater integration of the markets as well as the creation and strengthening of economic and monetary union.

The EPP's turn to the right after the integration of parties in the wake of the various enlargements has enabled the ALDE to be more federalist and liberal in the European Parliament, notably regarding societal matters[6]. However the ALDE has suffered some major defections (departure of the Portuguese PSD and the French UDF in the 1990's, and that of the Italian PD to the European Socialist Party in 2009), which questioned the party's ability to attract new partners. In 2009 it was the third political force in the Parliament and had 8 European Commissioners. It now only lies fourth.

The campaign and the results

In 2014, the ALDE appointed former Belgian Prime Minister (1999-2008) Guy Verhofstadt as its candidate for the Presidency of the Commission. The ALDE campaigned for greater integration of the financial markets and also for the simplification and reduction of European regulations, agricultural subsidies and the number of the Commission's areas of competence. It is also suggesting the organisation of an audit of all European institutions and it wants to introduce a mechanism to monitor the implementation of fundamental rights in Europe. It supports the signature of a free-trade agreement with the USA and with other major economic regions in the world[7]. The European Democratic Party is asking for the election of a single president of the European Union by direct universal suffrage, the introduction of European labour law and a European Small Business Act which would make it possible to reserve some public procurement orders for European SMEs.

The ALDE won the European elections in four Member States: The party of the Czech Finance Minister ANO 2011 won in the Czech Republic (16.1%, 4 seats), where thanks to the results of TOP09 and the KDU-CSL, the ALDE and the EPP gained a great deal of ground. In Estonia the right-wing in office won with 38.2% of the vote in all: the party of Prime Minister Taavi Roivas won with 38.2% for the ALDE taking 2 seats and the Centre Party won one additional seat. In the Netherlands the right-wing won 42% of the vote in all. The CDA (EPP) won 15.1% of the vote. In Belgium, the two liberal parties (Open VLD and MR) each won 3 seats.

The Liberals declined sharply in two Member States: in the UK, where the Liberal Democrats, David Cameron's partners in government lost 11 of their 12 seats and in Germany where the liberals of the FDP were only able to retain a quarter of their MEPs and plummeting from 12 to 4 seats. The liberals also lost their five seats in Romania after the change of affiliation of the National Liberal Party (now EPP).

1.3. The European Conservatives and Reformists

Created just days before the European elections in 2009 after the decision of the British Conservative Party and the Czech ODS to quit the EPP, the Alliance for European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) was the 5th party in the outgoing parliament. It is not a group as such but functions more like an association rallying 16 parties from the conservative, sovereignist right from 10 Member States in the Union and from four other countries.

The Prague Declaration (2009) is the group's founding charter. The text advocates a radical reform of the EU, defends the protection of sovereignty and the integrity of the Nation State and the defence of the link between Europe and NATO. In favour of minimum corporate regulations, reduced taxes and limited government, the group is liberal from an economic point of view but conservative regarding societal issues.

Opposed to the Lisbon Treaty, the ECR chose not to put a candidate forward for the presidency of the European Commission. Indeed the eurosceptics believe that there is no European political space in which citizens and representatives can claim similar sovereignty to that which exists on a national level.

The EPP and the ECR like to say they are complementary and united against the left. Relations between the two groups are variable however. Some EPP members have on several occasions criticised the instability of the ECR notably regarding David Cameron's positions on his country's membership (or not) of the European Union. Present negotiations about the Jean-Claude Juncker's bid for the Presidency of the Commission are a good example of the differences in view that exist between the two groups.

Results

*au 24/06/2014Source : European Parliament

*au 24/06/2014Source : European Parliament

The two main parties in the group suffered overwhelming defeat. The victory of the UK Independence Party (UKip) in the UK which had already been forecast, did however create surprise since it was the first time that another party other than the Conservatives or Labour had won a national election since 1918. David Cameron's Tories came third (23.3%) and lost 7 seats. The promises of a referendum about the UK staying in or leaving the EU, and prior to that, a renegotiation of the terms of London's membership treaty were not enough to prevent the rise of UKip.

In the Czech Republic, the Democratic Civic Party (ODS), a shadow of its former self, collapsed dropping from 9 to 2 seats. However in Poland Law and Justice (PiS) won 31.7% of the vote taking 19 seats, ie +7 in comparison with 2009. The ECR can also be happy with the result of the AfD in Germany (7% of the vote and 7 seats), which chose to join the group of which the German movement has now become the third political force.

Finally the four MEPs of the Flemish Nationalist (N-VA) came out ahead in the European elections in Belgium and also joined the ECR.

1.4. Outlook

On 22nd-25th May last the right again won the battle of credibility. In most Member States it seems to be the best placed to manage the economic crisis and to rise to the challenge of the upheaval faced by European society. Pragmatically the right has stolen the ideas (demand for regulation, moralisation and reform of capitalism) of a left - which now without a project - had no other choice but to rally to the austerity policy whose edges it merely proposes to round off.

Its victory in the European election and also its leading place within the European Council and the Commission allow the EPP to claim the presidency of the latter. Jean-Claude Juncker is a priori well placed to take over from José Manuel Barroso. Europe will therefore remain on the right and is due to continue with a budgetary austerity policy and the consolidation of public finances. "Growth cannot be founded on accumulating debt," declared the former Eurogroup president during the campaign.

2. The Social Democratic Left

Social democracy is one of the EU's European political families. Its organisation across Europe is old and complete. In the beginning the social democratic parties rallied within the Union of the socialist parties of the European Community in 1974, which then became the Party of European Socialists (PSE) in 1992. Within the S&D group in Parliament voting cohesion is high since it reached 90% in the last legislature 2009-2013[8].

2.1. The state of the social democratic family

The contemporary social democratic family is present in some EU Member States. It has been highly adaptable to the changes that have affected European society over the last few decades. The oldest parties have indeed succeeded in retaining their status of being the main force in political alternation, in spite of a reduction in the numbers of the working classes and the decline of the Keynesian paradigm. To a certain degree the observation might be extended to the new members since most are the legacy of former communist parties in the former East Bloc and which have survived democratic transition.

Paradoxically the first of the social-democratic family's weaknesses concerns its size. Its enlargement enabled it to remain the second group in Parliament and to welcome within its fold several government parties, but this has been at the cost of increased heterogeneity.

Rapprochement in terms of programmes, government action and the behaviour of its leaders have indeed been extremely slight, all the more so since the new eastern social democratic elements are also very diverse[9]. A second major weakness involves the structural weakening of the oldest social democratic component in Western Europe. A continuous process of electoral and member erosion has occurred over the last thirty years and this is now gathering pace. A third weakness involves the party's capability for ideological innovation. There has been no proposal comparable to that of the defunct "Third Way". Since the start of the crisis alternative proposals have not been sufficiently coordinated and have proven inadequate in the face of the issues at stake[10].

In sum the European social democratic family is one that has been brought together mainly in an artificial manner, uniting two main branches under the same roof. The first is Western. It is the oldest one and is the most homogeneous, but it is suffering a latent crisis in terms of its representativeness, its influence and its identity. The second is Eastern. It is both the most recent and more heterogeneous from an ideological, sociological and organisational point of view and it seems premature to declare that its constitutional phase is now complete.

2.2. Attitude to European integration and the electoral campaign

Undeniably the social democrats support European integration and belong to the political bloc that has driven it along (with the EPP and the ALDE). As of the 1980's the parties which remained hostile to European integration developed a more positive idea of it. This general winning over based on the hope of finding a viable space for social democratic policies has led to a regular support to the successive treaties - from the Single Act to the Lisbon Treaty and also the Maastricht Treaty.

Partisan divisions have occurred in that the European framework that has emerged has been interpreted as hostile to social democratic fundaments because of the primacy of negative integration (via the market and competition) or regulation of monetary policy by an independent institution insulated from politics[11]. This said the social democrats have found it difficult to make a serious challenge to the leading principles of the EU's economic policy to which their leaders in office have mainly subscribed in the national arena. Moreover the discomfort felt in the field has been compensated for by an exaltation of political and social Europe whose integration could not suffer - according to the social democratic elites - from a blockage of the community machine[12].

The social democratic European programmes have reflected this tension, eluding many debates over the EU's institutional and economic framework, whilst proclaiming the general goals of human progress and fiscal, social and environmental harmonisation between Member States. The manifesto published in 2009 did however represent a major step forward in a context in which the PES was able to draw up several real proposals, for example financial regulation or the pooling of sovereign debts. However the overall low influence held by European party federations, as well as the importance of the intergovernmental prevented these proposals from being implemented and finding any real institutional effect. More generally the crisis did not always allow social democracy to express its work better between the European level of government and the national, comprising many political communities whose political and social pace do not function in harmony.

From this point of view the electoral manifesto adopted in 2014 might even be deemed a step backwards in comparison to the text put forward five years ago[13]. It can be read as a typical (even caricatural) illustration of how to avoid the most vital issues of European integration shown by the lack of any reference to the European Central Bank. The consensus found on ten programme themes which contain very few real measures show that the PES is still united but not really integrated[14].

The 2014 campaign was marked by one innovation, ie the organisation of a campaign around the joint candidate for the Presidency of the European Commission. Martin Schulz, a German social democrat, President of the European Parliament after an agreement concluded with the EPP, was chosen by PES party members (without the support of British Labour, who deemed him too "federalist"). This choice seemed logical, given his investment and role (and by the Germans in general) in the European institutions, but also controversial, in that he embodied the persona of consensus and even the depoliticised nature of the European political system. Apart from in Germany, it was especially in France that Schulz was promoted the most - maybe less by conviction rather than necessity to prevent an overly nationalised intermediate election that was threatening an extremely unpopular government.

The slogan chosen by the French PS "Imposons une nouvelle croissance" (Let's push for new growth) - is a perfect illustration of the dilemma experienced by European social democracy which depends on the economy's expansion to promote its agenda and satisfy the most popular elements of its electorate. Generally the PES chose to direct its attacks against the Christian democrats defined as being those primarily responsible for the crisis and the poor response they provided whilst remaining silent about the support it had given to several of these responses (monitoring of national budgets, reduction of that of the EU). Regulation, harmonisation, softening of austerity programmes and social and environmental investments across Europe were promoted in campaigns that were mainly national and in appearance, very traditional.

2.3. The results

From 1979 to 1994 the social democrats comprised the leading group in the European Parliament. From then on the parties in this family started to decline, dropping from more than 27% of the vote on average in the 1980's to scores below 25% in 2004 and 2009. In the previous election the S&D group only won one quarter of the seats in Parliament, whilst it held more than one third 20 years ago. In this regard the results obtained this year are disappointing for the social democrats. The latter have only managed to stabilise the weight of their group at a modest level and have to be contented with second place from which they have not managed to extricate themselves since 1999.

Several things darken this "reassuring" table in terms of the stabilisation of the social democrats' results. Firstly if we no longer look at the relative size of the S&D group but rather the average number of votes won, there emerges a picture of continued electoral decline. The general average of the affiliated parties totals 20.2% (in comparison with 22% in 2009) and that of the "old" countries (ie the most traditional components of social democracy) 19.7%, a significant decline in comparison with the 22.4% won in 2009. Whilst the social democrats in the new member countries witnessed a rise and convergence of their scores with those in West five years ago they have now also experienced a decline (from around 23% to 21%, an average which is higher than the old member countries but boosted by the particular case of Malta)[15]. Neither participation in power nor being in the opposition seems to be a guarantee against electoral decline even though we might note that the highest scores were achieved by some parties in power like in Italy (40.8%) and Romania (37.6%).

Secondly some scores are particularly worrying. The "alert code" was reached in terms of some parties with government aspirations in several Member States. In the Netherlands, Labour found themselves below the 10% mark, behind the far left and D66. The Luxembourg socialists struggled to achieve 12% (in comparison with more than 19% 5 years ago), whilst the French PS - which was certainly used to mediocre results in this type of election - did not even reach the 14% mark (an historic low). In Hungary and in the Czech Republic, parties that were already doing badly, witnessed a further shrinkage of their score by over one third between 2009 and 2014. In Greece (-28 points), Spain (-15.5 points) and Ireland (-8 points), participation in "austere" governments was costly. Thirdly in many countries, all regions included, the weight of social democracy within the left has been diluted even in place where it has maintained its positions as in Sweden or Austria.

Regarding the balances within the S&D group the excellent performance achieved by Matteo Renzi's PD, now a full member of the PES, has enabled it to become the leading national delegation. With 31 MEPs, they are now greater in number than the 27 MEPs of the German SPD delegation. We should also note that the stabilisation of the social democratic group was enabled by this success which is that of a party led by a leader who was originally a Christian democrat; it was also supported by the good scores achieved by the Romanian coalition, which joined social democracy late and somewhat artificially; and by the recovery of the British Labour, which stands against Martin Schulz and greater European integration. The S&D group seems therefore to be a centre-left group in which the social democratic identity is becoming increasingly diluted and whose cohesion will require a great deal of work in view of the heterogeneity which prevails within it.

2.4. Outlook

In spite of their contrasted results the relative weight of the social democrats gives them a negotiation capacity with the Christian democrats and the liberals, but the simultaneous rise of the far left and right will encourage forms of collaboration beyond the left/right frontier more than ever before. The fact that the left, including the GUE/NGL have more MEPs than the EPP and the ALDE is only a question of a few votes, since the strategic rapprochement with the far left is made difficult by strong ideological differences. The old social democrat dilemma will be all the worse, of knowing how to influence a European context that is not open to their traditional principles whilst trying to defend their values and prove their political singularity to the citizens.

However the European Parliament will only be one of the places in which the solution to this dilemma will be found. The presence and influence of the social democrats in the national executives will be just as important from this point of view. But in many cases they only hold a minority partner status in existing government coalitions or they have to work with right-wing partners who do not share their ideas, this the very different world compared to the first post-war period, when it was a question of democratising regimes or to the second post-war period when it was a question of building a social State with the Christian democrats. Whilst "social democracy [...] has always wondered about alliances from an overall point of view: that of an alliance between social forces - itself serving a strategy of reform in social relations"[16], several examples of coalitions illustrate the collapse of any theoretical reflection, which hardly facilitates a different and/or coherent strategy on a European level.

3. The Greens and the Radical Left

During the 1990's the Greens allied to the regionalists, stole the fourth position in Parliament from the radical left, and became the second most important left-wing movement. The issues at stake in 2014 comprised a possible inversion of this balance of power, reflecting the recent electoral energy of some far left parties and the difficulty experienced by the ecologists to achieve results similar to 2009 in countries with high parliamentary quotas.

3.1. The Ecologist Family

The state of the ecologist family

The Greens are one of the rare new political families to have emerged in the European political arena since the end of the Second World War with the clear emergence of a series of national movements in the 1980's[17]. Its roots lie in the protest movements of the 1960's-70's notably committed to the defence of environments, against nuclear power, for peace and generally embodying the ethos of libertarianism and anti-productivism.

Unlike social democracy and the raical left, which resulted from class division and an obligation to adapt to the post-Fordist era, the Greens were the partisan expression of an alternative city life, that took on board deindustrialisation and the rise of culturally liberal values within new educated, socialised classes in a world of relative material abundance. We should not be surprised that studies undertaken on the typical profile of the ecologist voter depict him as to young, urban, highly educated citizens (often women), who are "permissive" about moral issues and extremely worried about environmental issues and life quality[18]. These features explain the unequal presence of ecological policy in the Member States, in that it is rare in the new Member States and highly concentrated in the countries of Northern Europe, which are more marked by the individualisation of values.

The origins of the Greens in the "new social movements" influenced the kind of parties they built in the initial years. These were typified by economy grass-roots organization which gives primacy to the collective, to ordinary activists over individual leaders and representatives. As the Greens integrated local and then national political life and also that the new social movements waned, these features did not disappear completely but a change took place. This was reflected in a distancing from the original model of organisation, due to the increasing professionalization of the party's leaders and representatives as well as its supporters[19].

Attitude to European integration and the electoral campaign

At the same time as this "normalisation" in the national arenas, the Greens have also adapted to the way the EU functioned whilst their principles have collided with the technocratic, intergovernmental and often opaque nature of the latter. The 1980's were marked by intense strategic and ideological debate (during which the alliance with the regionalists was challenged for a while), in that their democratic, decentralising, anti-military ideals were incompatible with both the existing EU and the prospect of a "Super Nation-State."[20]

The project of a "Europe of Regions" in spite of its weaknesses enabled a synthesis which combined the rejection of strong central power and a desire to articulate global awareness and local community. Having said this it is especially the quest for national government participation that has pushed the Greens towards growing acceptance of the EU's framework and the need to "play the institutional game"[21]. This was particularly noticeable in the support given to recent European treaties, which were criticised but approved on the whole, in the hope of turning this into a stepping stone towards a true constitutive process.

More recently the Greens have been the group with the greatest cohesion in the European Parliament (over 90%)[22]. During the campaign it stood out by organising a citizens' primary in the selection of a male/female couple to stand for the presidency of the Commission. The vote, which was organised on-line, was a failure from the point of view of turnout but the Greens are the only family to have opened their appointment process to the electorate. The heads of lists appointed were finally German Ska Keller, who was seen during the TV debates and Frenchman José Bové, who was not put to the fore as much as his colleague (including in France because of his controversial declarations about the "manipulation of living organisms"). The ecologist manifesto logically called for a "Green New Deal" focusing on the issues of climate, health, the protection of public freedom and democratic transparency - without laying down any real measures to be taken[23].

Results and outlook

The European elections traditionally seem rather supportive of the Greens. On the one hand low turnout tends towards the over representation of the more qualified electorate who belong to an electoral core. On the other hand these "secondary" elections lead to a more "expressive" vote providing the citizens with an opportunity to support alternative lists to the main government parties. Hence in the 2009 European election Europe Ecology-the Greens achieved their best score ever. Due to this exceptional success five years ago and also because of the participation of several ecologist parties in unpopular governments in this period of austerity, it seemed difficult for the ecologists to make any more progress.

*Representatives of the Greens and Rainbow Coalition groups / **on 24/06/2014 Source : European Parliament

*Representatives of the Greens and Rainbow Coalition groups / **on 24/06/2014 Source : European Parliament

Hence in the ballot boxes, as in parliament, we note a general stagnation on the part of the ecologist party. Its number of MEPs and its relative weight in parliament have declined in comparison with 2009 partly because of the departure of the MEPs of the NV-A (Belgium). Its final rank now places it behind the radical left by two seats. The defection of the Flemish nationalists is to the taste of the group's leaders whose priority it seems is to promote minimal homogeneity of values over the recruitment of all kinds of MEPs. However this will not prevent greater national diversity amongst the Greens/EFA MEPs. The German delegations and especially the French are declining: whilst they represented half of the group previously they now only count for one third, notably to the benefit of MEPs from Member States where ecologists were marginalised to date.

To be more precise the most notable progress made in comparison with 2009 can be seen in Sweden (+4.3 points) and Austria (+4.6 points), and also in countries like Hungary, where the ecologist score rose from 2.6% to 5%, in Croatia, Slovenia and Lithuania, where the ecologists made a breakthrough from a position of marginality; and also in Spain where the number of MEPs doubled (thanks to extremely different parties). However losses were recorded in countries where the Greens are traditionally established like in Germany (-1.4 points), the Netherlands (-1.9 points) and in Finland (-3.1 points). The group's loss of coherence does however have an upside ie the spread of the ecologist family beyond its traditional bastions now extends to Central and Eastern Europe. In comparison with the far left, another left-wing family that is not established across the entire EU, it has succeeded in placing MEPs in more Member States

3.2. The Radical Left

The State of the radical left

Since European integration started and the election of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage the political area to the left of social democracy has been marked by the collapse of the communist family. Of course some orthodox communist parties continue to exist to the left of social democracy. This said the present dynamics of this political space are based on other types of parties that are mainly established in Western Europe and include social democratic dissidents, former communists and "red-greens". Together they are defining the internal and external outline of a new family of parties[24].

Four major changes typify the handover from the communist family to the renewed radical left: there is no subordination to a foreign "centre"; it channels more diverse interests than simply those of the working class, notably those of the service sector and intellectual professions; the redrafting of a post-capitalist, also anti-patriarchal and sometimes ecologist project; the relinquishment of the mass party model to the benefit of thiner organisations, with an effort being made towards greater internal democracy.

In spite of recent electoral progress the family is still heavily handicapped. Firstly it still has no counter-model nor does it have a shared, mobilising utopia with which to oppose the present system (even though innovations might be noted like "ecosocialism"). Secondly, the collapse of communism has led to the decay of an entire intellectual, activist universe and of many popular supportive structures. As a result opinion leaders in society are few in number and are often ageing. Thirdly the radical left only exists electorally in half of the Member States with quite unequal results from one country to another.

Attitude to European integration and the electoral campaign

Many goals in the radical left's programme go against the present rules that govern the European Union. This explains why all of the parties in this family challenge the latter's institutional structure and its public policies, even though an increasing number of them are adapting to the EU as a framework to achieve an ideal of cooperation between people[25]. Unlike social democracy the radical left clearly wants new treaties to be drafted that will notably guarantee the primacy of social rights over economic freedoms, increased democratic monitoring of economic life and the end of links between the EU and NATO.

European integration is still a subject of division which is much stronger than in other left-wing families. Until the 1970's the communist parties were radically against it. Later positions were more varied and reconciling these was not easy, hence the existence of two different groups between 1989 and 1994. A European federation of parties (the Party of the European Left) was only born in 2004, whilst the parliamentary group GUE/NGL (European Unified Left/Nordic Green Left) is not really integrated. It functions according to a confederal model and its internal cohesion during voting is one of the lowest in the European Parliament (80%), especially during votes on issues concerning supra-nationality (60-70%)[26]. Positions are spread between a minority which basically rejects European integration and a majority of "alter-Europeans" who support integration but reject some aspects of it. In fact they refer to one main issue: is neoliberalism in the EU's fundamental nature or can it be countered as part of this supranational construction?

At present it is the second option that prevails as illustrated by the choice of Alexis Tsipras, the Greek leader of Syriza, as candidate for the Commission. He mainly campaigned against austerity and for a "New Deal" across Europe, implying a new status for the ECB and the renegotiation and even the partial cancellation of certain government debts. The manifesto of the European Left Party tried more widely to put forward a new social and also ecological model (criticising the transatlantic treaty as an absolute counter-example), whilst remaining vague about the political and institutional strategy to follow[27]. Successful from a personal point of view the Tsipras campaign also favoured putting together a single list of the far Italian left. This said, the lack of financial means and the strong nationalisation of the campaigns prevented there being any real effect on the results achieved.

Results and outlook

The radical left's representation suffered the collapse of the communist family all the more so since the group was deserted by many Italian Communist Party MPs. Over the last few years the radical left has also suffered due to its absence from most of the new Member States. Structurally the European elections are not a good election for it in that the radical left parties prosper rather more when electoral turnout is high, which implies the participation of the popular classes.[28].

The GUE/NGL group has 52 seats which take it to fifth position in the European Parliament, rising just above the ecologist group which outstripped the radical left in 1989. The most important detail to remember is rather more the recovery of a relative weight that is comparable to that it enjoyed 15 years ago on the basis of the number of MEPs which has increased by 50% in comparison with 2009. This result reflects the dynamics of the radical left even though it is focused in a small number of countries.

The group's internal composition reveals a balance of power that fosters the parties that do not belong to the most orthodox communist branch, especially since the two MEPs of the Greek KKE relinquished their seats within the group. A strategy privileging more involvement in the community process might result from this. This will very much depend on the ability of the biggest groups of MEPs to motivate the others, ie those from Die Linke and Syriza (one quarter of the group). The marginalisation of the "old" communist elements does not mean however that the affiliated parties' victory is total. The group's heterogeneity will be high with the entry of many MEPs who are on the left of their national political arenas, but who are only slightly or not at all involved in the building of a true radical left family like the five MEPs of Podemos (Spain), those of the Basque or Irish nationalist left and even the parties defending animal rights (Netherlands and Germany).

Electorally the contrast between a sharp ascension in Greece and Spain and relative stagnation in other countries (except in Ireland where Sinn Fein gained 6 points) has struck all observers. This can be explained by the degree of severity of the austerity regimes, but this does not work in Portugal's case (where the entire radical left is on the decline) or in Italy (where this trend is still very weak). The forces which made sharp breakthroughs or gained ground in Greece and Spain were especially able to take advantage of strong autonomous social movements and of having succeeded in involving themselves subtly, cultivating strong but not dominating links with civil society[29]. More generally however the dynamics that were solely national explain best the results achieved in each Member State. Hence it is impossible to understand the lack of progress made by the Left Front in France (in spite of the collapse of the revolutionary far left and the Socialist Party) without taking on board its internal problems and the poor management of the party after the presidential election.

4. Far right, radical or populist right

On 14th November in Vienna several far right European parties met on the initiative of Andreas Mölzer, then an FPÖ MEP (Austria). At the meeting that day were Marion Maréchal-Le Pen and Ludovic de Danne for the Front National, Kent Eckeroth for the Swedish Democrats, Andrej Danko for the Slovakian National Party and also Lorenzo Fontana of the Lega Nord and Philip Claeys of the Vlaams Belang[30]. This was another bid on the part of the "mutant" far right parties in Europe[31] to organise after several episodes that we might briefly recall here:

- During the 1979 elections an alliance called "the euroright" was born, in which the Italian Movimento Sociale Italiano–DestraNazionale (MSI-DN) and the Spanish FuerzaNuova, took part to the benefit of the New Forces Party (PFN), led by Pascal Gauchon, Alain Robert and Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour.

- From 1984 to 1989, with the same MSI-DN, as well as a unionist MP and a Greek far right MP, the Front National formed the "Group of the European Right" which then left the MSI-DN (led since 1987 by Gianfranco Fini) but which was joined by the German Republikaner led by Franz Schönhuber.

- In 1989, the "Technical group of the European Right" was formed, comprising MEPs from the Front National, the Republikaner and one MEP from the Vlaams Blok (Belgium). It was dissolved in 1994.

- From 1999 and 2001, another "Technical group of Indedpendent MEPs" (TDI) included the representatives from the Emma Bonino group, Front National MEPs and those from the Lega Nord and the representative of the MovimentoSoziale-Fiamma Tricolore (MS-FT).

These periods as well as the present turmoil in terms of forming a group in the European Parliament under the chairmanship of Marine Le Pen, show that there is no real organisational unity for this family in Europe. Ideological and geopolitical opposition make this a problem as illustrated by the difficulty in reconciling the Russophile vision of Marine Le Pen with the Baltic far right - particularly the Lithuanians of TT (11% in their country) who are against it.

4.1. The state of the far right in Europe

There are several far right party categories. Apart from the FN and FPÖ alliance there are other parties which really are more genuinely neo-Fascist and even neo-Nazi. Hence we can define two types of party:

- the parties which find their origins or not in the traditional far right and have adopted or are progressively adopting a new agenda, which is more "populist". They are formally respectful of democracy and even claim the defence of democracy, try to promote individual rights, and they are often hostile to Islam and its presence in Europe. Here there are parties, which in spite of the turmoil, accept working together: FN (France), Lega Nord (Italy), PVV (Netherlands), FPÖ (Austria), SD (Sweden). There is also the Dansk Folkeparti (DF), founded by Pia Kjaesgaard in 1995. This is a radical right party which supports the centre-right governments in its country[32]. It also maintains a distance from the other ideologically comparable parties in Europe, like the FN, with which it refuses to work on any level.

- There are the more traditional extreme right parties, which are anti-democratic, unequal, often racist, for example Forza Nuova in Italy, Jobbik in Hungary, Ataka in Bulgaria. They can also be of neo-Nazi inspiration like the NPD in Germany and also Golden Dawn in Greece.

The FPÖ, leading in the first category, is chaired by Hans-Christian Strache. He has progressively won back some electoral positions after the successive crises suffered by the "Austrian liberal" family in the 2000s: electoral difficulties, strategic differences in opinion between Andreas Mölzer and Jörg Haider, secession by Jörg Haider and the creation of the BZÖ in 2005, accidental death of Haider in 2008. In the general elections of September 2013 the FPÖ won 20.5% and the BZÖ collapsed taking only 3.53% of the vote which was not enough to rise beyond the vital threshold to be represented in the Austrian Parliament. Both were running against the Stronach Party (5.7%). The FPÖ's line has grown more radical in comparison with the Haider period. Now the "SozialHeimatPartei" (Social Homeland Party), the FPÖ has copied Haider's slogan that was adopted in the 1990's (" ÖsterreichZuerst ! " - Austria First!), is against the euro and vehemently criticises European governance, whilst Haider had taken a "euro-enthusiastic" turn with the BZÖ[33]. The FPÖ is not trying to form any more alliances with the Christian democrats of the ÖVP and is no longer participates in government.

Italy is a particularly interesting case. The integration of the MSI-DN into the political layout of the Second Republic then the integration of Alleanza Nazionale (AN, the MSI-DN's new name adopted in 1995) finalised its ideological re-orientation which was effected after a split (that of the friends of Pino Rauti, which rallied the MSI-DIN in 1972 and which created the MS-FT). Until its merger with Forza Italia in the PDL, AN had more radical members, some of whom left to create La Destra. Another far right party, Lega Nord established alliances with Forza Italia and Silvio Berlusconi as of 1994, but their relations were particularly tumultuous and frequently ended in dislocation or the weakening of the centre-right coalition in office in Rome[34]. The new leader Matteo Salvinia decided to place emphasis on opposition to the euro, to the institutions and to EU governance. The Lega Nord has returned to a low-ebb of 5% stabilising its results after an extremely troubled period due to a series of internal scandals.

Finally the European far right is extremely heterogeneous and this is reflected in the diversity of ideas about Europe which these parties hold.

4.2. Attitude to European integration and the electoral campaign

"Europe for the Europeans" and "Down with Brussels!" might summarise the main trends in the development of the radical and populist right in Europe.

The European Alliance for Freedom is counting on the aggiornamento of the European far right. It rallies the FN, FPÖ, the VB, the Lega Nord, the Slovakian National Party. It is based in Malta and chaired by Franz Obermayr (FPÖ). Without any statutes it is an organisation which maintains respect for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention of Human Rights. Its political goals are established so that they are compatible with the framework of the European Union. The EAF maintains that it is working for "transparency", "democratic control" in view of preventing the establishment of a "Super State". "Subsidiarity" and sovereign national parliaments are also defended by this structure which declares that it wants to protect "diversity" and the "freedom of expression". The nations of Europe must be able to exercise their "right to strengthen their own historic, traditional, religious and cultural values." Finally the defence of civil liberties runs alongside the fight to "counter the totalitarian" tendencies of the European Union. Former MEP Andreas Mölzer, is one of the craftsmen of the rapprochement that has been made by these parties. In 2005 he tried to find common ground on the idea they were to have of Europe. He saw it as a set of "ethnic communities" whilst the French FN saw it as a set of "European nations."

Indeed there are different types of opposition to Europe or scepticism about the way it is being shaped. With the notable exception of the BZÖ, which did not survive the death of its leader, the radical right and populist parties in Europe have a hostile discourse. However there are different European "utopia" amongst the parties in question. Some like the FN like the idea of a "Europe of homelands" others like the Vlaams Belang support a Europe of "ethnic communities", the Swedish Democrats try to denounce the "European Super State" whilst accepting the principle of European cooperation. Like Cas Mudde we might qualify this attitude to Europe as "terminological chaos."[35]

In all events there is no common ideal of Europe but these deep ideological differences do not impede joint work within the European Parliament. Hence the Vlaams Blok/ Vlaams Belang has always worked with the FN ,which has a totally opposite idea of Europe and of the rights of the Flemish minorities.

The Front National undertook a campaign on the theme "No to Brussels, yes to France" thereby implying its rejection of seeing any supranational power on a continental or world level. Its discourse in defence of the Nation-State as an uninfringeable framework in terms of democracy and solidarity is traditional. In the past when there was secession with the supporters of Bruno Mégret a difference emerged with the latter maintaining, unlike Jean-Marie Le Pen's supporters, that he believed in the need for a "powerful Europe."

In conclusion there is no party that supports the present governance of Europe nor is there a common vision of Europe amongst these parties. Although the FN's delegation is now by far the biggest far right movement in the Strasbourg hemicycle - thanks to the combined effect of demography and the score achieved on 25th May 2014, it seems pertinent to wonder about its real hegemony amongst the parties of the same political "family" in Europe. Indeed it is not at all clear that its idea of Europe prevails amongst the other radical or far right parties. Working together with the other parties may also make it change its attitude to European integration.

4.3. The results

Since 1979 the far right has always been present in the European Parliament, but until 1984, only the Italian MSI-DN represented it. For a long time it was the oldest far right party in the European Parliament until its ideological and organisational change on 27th January 1995 "Svolta de Fiuggi"- and its change of political direction which led it to form alliances in Europe with parties like the French RPR.

The following table covers the far right's results when it succeeded in forming a group in the European Parliament. As of 2004, the radical right sovereignists' score (but which cannot be considered together as a far right group in the strict sense of the term) is indicated in italics and matches the present trend of the EFD.

* au 24/06/2014. 1984-89 : Groupe (technique) des droites européennes ; 1999 : Groupe technique des députés indépendants; 2004 : Groupe Indépendance/Démocratie ; 2009 : Groupe Europe de la liberté et de la démocratie ; 2014 : Groupe Europe de la liberté et de la démocratie.

* au 24/06/2014. 1984-89 : Groupe (technique) des droites européennes ; 1999 : Groupe technique des députés indépendants; 2004 : Groupe Indépendance/Démocratie ; 2009 : Groupe Europe de la liberté et de la démocratie ; 2014 : Groupe Europe de la liberté et de la démocratie.

Source : European Parliament

Of course the FN's score is the most spectacular of the results of this family. It is also the biggest French delegation (23 seats) and this could have guaranteed it pre-eminence in a possible group. With 24.95% of the vote the FN achieved its best score ever in both a national and European election.

The Lega Nord, with 6 MEPs maintains its score (equal to that of 1994 and 2 points higher than in 1999 and 2004 but three points lower than its 2009 score of 10.21%). The FPÖ, won 19.5%, and four seats. It competes with no one, neither with Franck Stronach, nor the BZÖ. In Denmark, the DF won an historic score of 26.6%, nearly 7 points ahead of the social democrats and achieving a leap of more than 11 points in comparison with 2009. The Swedish Democrats won 9.7% of the vote but refuse to work with the FN - which it did however draw close to - likewise the DF did a long time ago.

Amongst the groups which are more genuinely neo-Fascist or neo-Nazi the scores of Jobbik in Hungary (14.7%) and Golden Dawn in Greece (9.4%) make them the main representatives of this category. Thanks to a change in the rule governing electoral representativeness the NPD in Germany now has a seat in the European Parliament. The traditional extreme right (or "old" extreme right) continues however to be marginal in the European Union.

The difficulty or failure of Marine Le Pen in forming a group in the European Parliament was made more acute by the traditional presence of eurosceptic parties which are really part of the radical right. Hence UKip, led by Nigel Farage, was able to form a group with parties like the Five Stars Movement (M5S) led by Beppe Grillo. The resources that Nigel Farage can mobilise (MEP since 1999) are greater than those of the FN - which has been isolated for a long time within the Strasbourg Assembly. Accustomed to working with other eurosceptics Mr Farage has been able to attract the "Grillists" as well as parties from the far right like the Swedish Democrats (SD) or members of the Lithuanian far right party as well as a defecting FN MEP.

Outlook

There is no unity amongst the extreme right, radical right or the populists in Europe. Difficulties in putting together a group owe as much to economic differences as well as to the impossibility of establishing a common ideological base about Europe. Political work undertaken for over a decade by Andreas Mölzer only covers a part of the range studied. However it is around the FN, the FPÖ, the PVV and the Lega Nord that there now seems to be a nascent Europeanisation of the radical right in Europe.

ANNEXES

(Source : European Parliament)

[1] Pierre Martin, "Le déclin des partis gouvernements en Europe", Commentaire, n°143, 2013, pp. 543-554.

[2] Regarding the EPP's history, Pascal Delwit (dir.), Démocratie-chrétienne et conservatismes en Europe : une nouvelle convergence, Bruxelles, Editions de l'ULB, 2003 ; Pascal Fontaine, Voyage au cœur de l'Europe, 1953-2009 : histoire du groupe démocrate-chrétien et du European People's Party au Parlement européen, Brussels, Racine, 2009, Agnès Alexandre-Collier et Xavier Jardin, Anatomie des droites européennes, Paris, Armand Colin, 2004..

[3] Website Votewatch : http://www.votewatch.eu/en/political-group-cohesion.html

[4] Website Votewatch : http://www.votewatch.eu/en/political-groups-power.html

[5]EPP Electroral Manifesto. Dublin Congress, 6th-7th March 2014, available on http://dublin2014.epp.eu/wp-content/uploads...

[6] On the history of the Liberals, Pascal Delwit (dir.), Libéralisme et partis libéraux en Europe, Brussels, Editions de l'ULB, 2002.

[7]Une Europe à votre service, http://www.aldeparty.eu/sites/eldr/files/...

[8] Internet site Votewatch : http://www.votewatch.eu/en/political-group-cohesion.html

[9] Jean-Michel De Waele, Fabien Escalona and Mathieu Vieira (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Social Democracy in the European Union, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

[10] David Bailey, Jean-Michel De Waele, Fabien Escalona and Mathieu Vieira (eds), European Social Democracy During the Great Economic Crisis : Renovation or Resignation ?, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2014.

[11] Fabien Escalona, " La primauté du politique en danger " (http://fabien-escalona.blogspot.fr/2013/0...)

[12] Michael Holmes, " Evaluating the Left and European integration from the European Constitution to the Treaty of Lisbon ", Notes de la Fondation Jean Jaurès, April 2014.

[13] See the PSE Manifesto " Together for a Better Europe ", available on http://www.pes.eu/.

[14] Fifteen years on we might look at the diagnosis put forward by Gerassimos Moschonas as it stands: "The continued publication of programmes using the same minimum minimorum proves that the distance to cover in vue of real cohesion [...] is still great. Moreover minimalist programmes are not likely to turn into tools of action" (in " Socialistes: les illusions perdues ", in Gérard Grunberg et al. (dir.), Le vote des Quinze, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2000, pp. 135-162).

[15] For the 2009 election refer to Alain Bergounioux and Gérard Grunberg, " La social-démocratie européenne au lendemain des élections de 2009 ", Revue politique et parlementaire, n°1052, 2009, pp. 123-137.

[16] Daniel-Louis Seiler, "La social-démocratie et le choix des alliances et des coalitions", in Pascal Delwit (dir.), Où va la social-démocratie européenne ?, Brussels, Editions de l'ULB, pp. 105-136.

[17] Daniele Caramani, " Electoral waves: an analysis of trends, spread, and swings of votes across 20 west European countries, 1970–2008 ", Representation, vol. 47, n°2, 2011, pp. 137-160.

[18] Jérôme Vialatte, Les partis Verts en Europe occidentale, Paris, Economica, 1996 ; Martin Dolezal," Exploring the stabilization of a political force: The social and attitudinal basis of Green parties in the age of globalization ", West European Politics, vol. 33, n°3, pp. 534–552.

[19] E. Gene Frankland, Paul Lucardie et BenoîtRihoux (dir.), Green Parties in Transition, Aldershot, Ashgate, 2008.

[20] Elizabeth Bomberg, Green Parties and Politics in the European Union, London, Routledge, 1998

[21] Michael Holmes, op.cit.

[22] Site internet Votewatch : http://www.votewatch.eu/en/political-group-cohesion.html.

[23] Joint Green Manifesto for 2014, " Change Europe, Vote Green ", available on http://europeangreens.eu/

[24] Fabien Escalona et Mathieu Vieira, " Radical Left in Europe : Thoughts About the Emergence of a Family ", Notes de la Fondation Jean Jaurès, Paris, Fondation Jean Jaurès, 2013.

[25] Michael Holmes, op.cit.

[26] Site internet Votewatch : http://www.votewatch.eu/en/political-group-cohesion.html.

[27] Manifesto of the European Left Party for the European Elections 2014, available on http://www.european-left.org/

[28] Luke March, Radical Left Parties in Europe, London, Routledge, 2011.

[29] MyrtoTsakatikaet Marco Lisi, " Zippin' up My Boots, Goin' Back to My Roots: Radical Left Parties in Southern Europe ", South European Society and Politics, vol. 18, n°1, 2013, pp. 1-19.

[30] The Vlaams Belang, resulting from the Vlaams Blok, competes in Belgium with the Flemish Nationalists NV-A.

[31] Gaël Brustier, " Mutation des nouvelles extrêmes droites européennes : un défi pour la gauche ", Notes de la Fondation Jean Jaurès, Paris, Fondation Jean Jaurès, 28 January 2014 ; Jean-Yves Camus, " Extrêmes droites mutantes en Europe ", Le Monde diplomatique, March 2014.

[32] Cas Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 162. His daughter tried to take up this discourse quite briefly when she took over this party's list.

[33] Cas Mudde, op.cit., p. 43

[34] It was the case in December 1994 when the Lega Nord brought down the first Berlusconi government and also during Berlusconi's last government during which jt took the side of the Economy Minister Giulio Tremonti, against the political line of those close to Gianfranco Fini.

[35] Cas Mudde, op.cit., pp. 165-167.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Climate and energy

Valérie Plagnol

—

22 April 2025

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :