Institutions

Yves Bertoncini,

Thierry Chopin

-

Available versions :

EN

Yves Bertoncini

Consultant in European Affairs, Lecturer at the Corps des Mines and ESCP Business School

Thierry Chopin

1. An initial criterion: The president of the Commission's party affiliation

- All of the recent presidents of the Commission have had to rely on majority support from MEPs from the right and from the left (EPP-PES, and even the Liberal Democrats) but the president of the Commission's party affiliation has only one out of two matched that of the party which garnered the highest number of votes in the European elections (see Table 2).

- The party affiliation of the president of the Commission has reflected that of the party most heavily represented on the European Council (see Table 3) over the past twenty years (the Santer, Prodi and Barroso Commissions), yet it failed to do so in the years prior to that (the Delors and Thorn Commissions).

2. A crucial criterion: the president of the Commission's personal profile

- The president of the Commission should be chosen first and foremost on the strength of his ability to perform the functions described in Article 17 of the Treaty on the European Union.

- Is the custom of designating figures who have held the post of prime minister in their own country going to prevail once again?

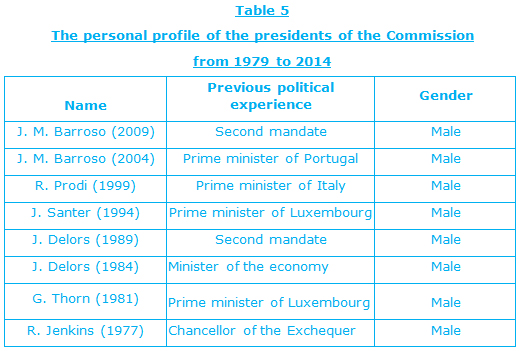

- All the presidents of the Commission appointed since the beginning of the European construction process have been men - is the candidate's gender going to be one of the criteria invoked in 2014?

3. A major criterion: the president of the Commission's country of origin

- The demographic aspect: the office of president of the Commission has been held by nationals from countries of different sizes (see Table 6).

- The geopolitical aspect: an analysis of the geographical origin of the recent presidents of the Commission points to a certain desire for balance between the West, the South and the Northwest; it also reveals the desire to appoint a candidate from one of the countries most heavily committed to European integration (the Schengen area and the euro area).

- The historical aspect: the length of time that a candidate's country has been a member of the EEC or of the EU does not appear to have any impact on the choice of the president of the Commission.

4. From an MCQ to Rubik's cube: the impact of designations to other European and international posts

The choice of the president of the Commission is made in a specific institutional and diplomatic context, and it is based on consideration of:

- the other posts that need to be assigned at the European level (see Table 7): the president of the European Council, the vice-president of the Commission / high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy, the president of the European Parliament and the president of the Eurogroup;

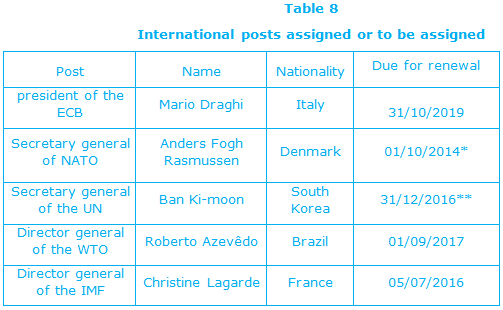

- positions already held in other European and international organisations (see Table 8), in particular the posts of president of the ECB or of director general of the WTO or the IMF.

In any event, it is important for the European Council's and European Parliament's joint choice to be made clearly, both with regard to its substance (the nature of the criteria adopted) and with regard to its form (transparency in the negotiations and in the voting).

Introduction: neither Westminster nor Westphalia?

The campaign for the European elections on 22-25 May 2014 prompted five large parties to designate their candidates to the presidency of the Commission, a welcome democratic innovation which made it possible to put "faces on divides"[1] in Europe's political life, transcending the mere "pro/anti-EU" divide. The candidates whose parties garnered the highest number of votes are now in the front line in the context of the negotiations currently under way between the European Council and the European Parliament which are called on once again, just as they have been in the past, to reach agreement on the designation of the president of the European Commission between now and 2019.

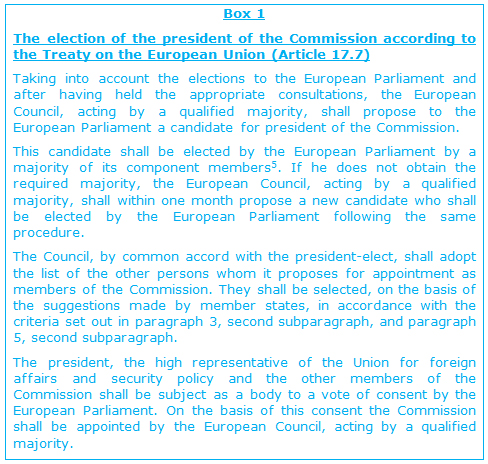

This, because the Treaty on the European Union states (see Box 1 below) that it is the responsibility of the heads of state and government, acting by qualified majority and "taking into account" the result of the European elections, to propose a candidate to the European Parliament, which then has to hear that candidate and subsequently elect him or her[2] by an absolute majority of its members (i.e. by at least 376 votes out of 751)[3].

So the text of the treaties is clear on one point, on which the Treaty of Lisbon has not changed anything at all: the heads of state and government cannot impose a candidate of their choice on the basis of purely diplomatic negotiations, as was the case back in the days of the Treaty of Westphalia, and without the formal approval of the European Parliament. But neither does the text of the treaties lend itself solely to the interpretation subscribed to by numerous parties involved in the spring 2014 election campaign: it does not guarantee that the new president of the Commission is necessarily going to be one of the candidates who have sought the electorate's votes, or even that he or she will come from the ranks of the party that garnered most votes in the election[4].

This, because the European Union does not (yet?) work along the lines of the "Westminster regime", where the British prime minister has to be the candidate of the party having won most seats at the House of Commons in order to be able to fulfil that role, while the Queen/King has no option but to take note of the verdict that has emerged from the election. In legal terms, no European text specifies that the next president of the Commission has of necessity to have stood for election in the European elections (the previous presidents certainly have not done so). On the political level, the European Council can hardly be compared to the Queen of England because it enjoys its own legitimacy, a legitimacy which is in fact borne out by the treaties. The Treaty on the European Union stresses that it rests on a dual form of legitimacy: that of the member states and that of the citizens (in particular in Article 10), echoing Jacques Delors' formula describing a "European Federation of nation states": and it seems to be particularly appropriate to evoke this dual civic and governmental legitimacy when talking about the designation of the president of the Commission, which rests on a joint agreement between the European Council and the European Parliament.

The conflict of interpretation surrounding the political terms for the designation of José Manuel Barroso's successor makes it more necessary than ever to clarify the negotiations currently getting under way between the European Council and the European Parliament, but also among the EU's member states, and among the political parties and groups. To do this, it is necessary to illustrate all of the criteria and factors which, as in the past and in the political situation created by the recent election campaign, are likely to influence the joint choice of the European Council and of the European Parliament. In this context, if we look at the content and the conclusions of the negotiations that have been held since MEPs have been elected by direct universal suffrage, we can see that these criteria are likely to fall into one of the following four categories:

- the candidates' party affiliation (§1);

- the candidates' personal profile (§2);

- the candidates' country of origin (§3);

- the impact of the appointments to other European or international posts (§4).

1. A key criterion: the president of the Commission's party affiliation

The campaign leading up to the European elections on 22-25 May 2014 witnessed a major innovation compared to past campaigns, namely the designation by five European political parties of their candidate to the presidency of the Commission: Jean-Claude Juncker for the European People's Party (EPP), Martin Schulz for the Party of European Socialists (PES), Guy Verhofstadt for the Liberals and Democrats (ALDE), José Bové and Ska Keller for the European Greens and Alexis Tsipras for the European United Left (GUE).

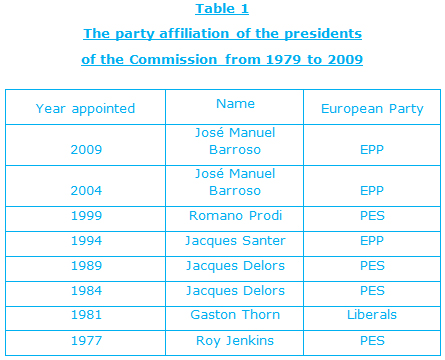

Yet this innovation should not conceal the fact that the Commission's previous presidents also had specific party affiliations when they were appointed (see Table 1). Thus the six presidents of the Commission to have taken office[6] since MEPs have been elected by direct universal suffrage have been affiliated respectively to:

- the PES (three: Romano Prodi, Jacques Delors and Roy Jenkins);

- the EPP (two: José Manuel Barroso and Jacques Santer);

- the Party of Liberals and Democrats (one: Gaston Thorn).

By the same token, their predecessors[7] were also members of, or affiliated to, the EPP (two: Walter Hallstein and Franco Maria Malfatti), the European Party of Liberals, Democrats and Reformists (one: Jean Rey), the PES (one: Sicco Leendert Mansholt) and even the "Gaullist" party (one: François-Xavier Ortoli).

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé

The designation of candidates to the presidency of the Commission by the main European parties has certainly reshuffled the political cards to some extent, including with regard to the substance of the balance of forces established by the two institutions that are going to be thrashing out an agreement on the next president of the Commission. Yet it does not prevent us from drawing useful conclusions from previous negotiations with regard to the party balances in force in the European Parliament and in the European Council, and to the appointments that those balances subsequently spawned.

1.1. The importance of party balances in the European Parliament

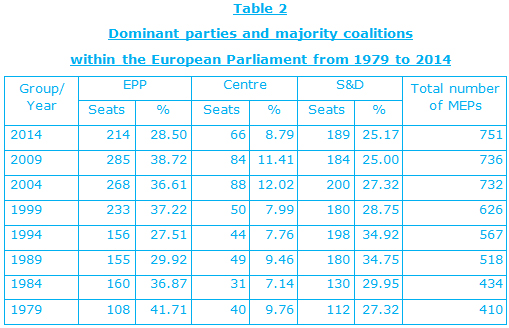

In view of the one-round proportional system adopted in the European elections, which benefits small parties and prevents any single party from having an absolute majority of seats on its own, all of the European Commission's past presidents have had to be approved by a coalition comprising several parties. Generally speaking (see Table 2 and the detailed table in Appendix 1), the results in terms of seats have led to what has inevitably been cross-party support, particularly since a vote of approval became compulsory, in other words since the Treaty of Maastricht came into force in 1994.

In this context, a comparison of the party affiliation of the presidents of the Commission (see Table 1) and of the party balances within the European Parliament (see Table 2 and the detailed table in appendix 1) produces a decisive distinction whereby:

- all of the recent presidents of the Commission have had to rely on majority support from MEPs from the right and the left (EPP-PES, and even the Liberal Democrats;

- the president of the Commission's party affiliation has only one out of two matched that of the party which garnered the highest number of votes in the elections and held the largest number of seats in the European Parliament.

Thus José Manuel Barroso (EPP) was confirmed twice by a European Parliament in which the EPP was the dominant group, while Jacques Delors was confirmed in 1984 by a European Parliament dominated by the Socialist group. But that did not happen in the case of Romano Prodi (PES) who was approved in 1999 by a European Parliament where the EPP was the dominant group, or of Jacques Santer (EPP) who was approved in 1994 by a European Parliament in which the PES was the dominant group. And it is also worth underscoring the fact that Liberal Gaston Thorn held the post of president of the European Commission at a time when the PES held the largest number of seats in the European Parliament, only just ahead of the EPP but way ahead of the Liberal Democrats.

In view of the above, it seems all the more risky to hazard the prediction that the next president of the Commission is bound to come from the ranks of the party with the largest number of seats in the European Parliament because his or her nomination will be taking place in a broader political context which includes appointments to other top European posts (see §4 below).

Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/... ; layout and calculations by Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/... ; layout and calculations by Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Centre = ELDR/ALDE / 1989: Centre = LDR / 1984 and 1979: centre = L

1.2. The impact of party balances within the European Council

While tasked with designating the president of the Commission since the very beginning of the European construction process, the heads of state and government have had to find a modus vivendi with the European Parliament's vote of approval since 1994. Have they allowed their conduct to be governed primarily by party rationales, or have they also allowed other aspects, especially personal (see §2) and diplomatic (see §3 below) considerations, to influence their negotiations initially within their own and subsequently with the European Parliament?

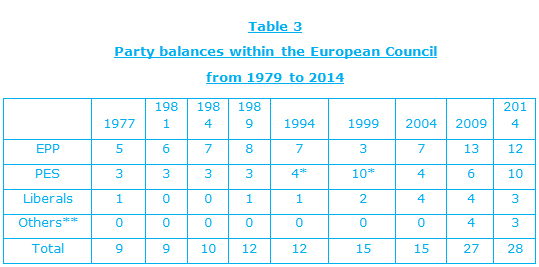

A comparison between the party affiliation of the various presidents of the Commission (see Table 1) and the party balances within the European Council (see Table 3 and the detailed Table in Appendix 2) sheds instructive light on the whole issue, suggesting that:

- the party affiliation of the president of the Commission has indeed reflected that of the party most heavily represented on the European Council over the past twenty years, thus with Jacques Santer (EPP) in 1994, with Romano Prodi (PES) in 1999 and with José Manuel Barroso (EPP) in 2004 and 2009;

- on the other hand, the party affiliation of the president of the Commission did not reflect that of the party most heavily represented on the European Council when Jacques Delors (PES) was appointed both in 1984 and in 1989, or when Gaston Thorn (Liberal) was appointed in 1981.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

NB: The political affiliations given are those of the heads of government at the time of the European elections and of the designation of the president of the Commission.

* In 1994, France had a Socialist president of the republic but a right-wing prime minister, while in 1999 the opposite was true: here we take the president's party affiliation into account.

** ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists / EL: Party of the European Left / NA: Non-attached / EPP: European People's Party / PES: Party of the European Socialists / ALDE or EDLR: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe or European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party

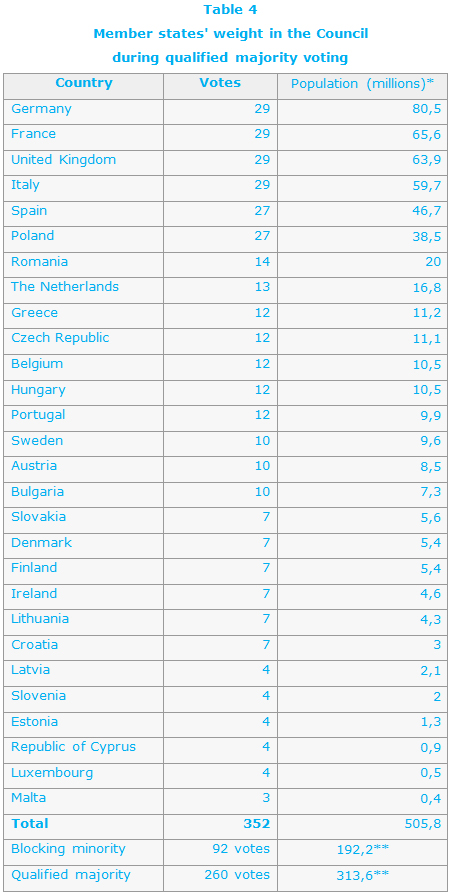

It is worth pointing out that the need for a unanimous vote on the European Council's part to designate the president of the Commission (until the Treaty of Nice came into force) inevitable demanded the formation of a cross-party consensus, because it would have been unlikely for all of the heads of state and government to belong to the same European party, or even to come from the same side of the political divide (left or right). The fact that the president of the Commission is now designated by a qualified majority vote in the European Council makes it impossible for a single head of state or government to veto a designated candidate, but it still allows a handful of member states (on the basis of the size - see Table 4) to set up a blocking minority against his or her appointment[8]. A qualified majority vote can also require the forging of a cross-party consensus regardless of the prevailing political circumstances, giving the right or the left a very broad majority because it is obvious that state or national rationales can also prevail in the heads of state and governments' choice.

*données Eurostat 2013

*données Eurostat 2013

** la majorité qualifiée doit recouvrir en outre 62% de la population de l'Union européenne pour être valable

All in all, an analysis of party balances within the European Parliament and the European Council in past rounds of negotiations to designate the president of the Commission does not allow us to unambiguously clarify the role likely to be played by this factor in the negotiations currently under way. This factor could be crucial, not to say decisive, if the European political parties that have already designated their candidates to the presidency of the Commission were to defend to the hilt the position whereby the next president needs to be chosen from among those candidates, without that necessarily guaranteeing, however, that the president will come from the ranks of the party group which garnered the highest number of votes. It could also become of only relative importance if it is decided first to thrash out the specific substance of an action programme capable of winning majority approval in the European Parliament and in the European Council, and of deciding on the name of the president of the Commission best suited to represent and to implement that programme only thereafter.

The party affiliation of the next president of the Commission could be particularly uncertain in view of the fact that one of the questions asked of the MEPs and the heads of state and government will be to consider whether the change in the balance of forces between the election of 2009 and that of 2014 (and within the European Council over the same period) has been such as to plead for a return to the status quo ante (in other words, assigning the presidency of the Commission and the presidency of the European Council to the EPP, and the post of vice-president of the Commission and high representative for a common foreign and security policy to the S&D), or whether it should not rather lead to a new party balance in the assignation of these three posts.

2. A crucial criterion: the president of the Commission's personal profile

In view of the balance of forces established between the European Parliament and the European Council for the next president of the Commission's designation, it is likely that the candidate's personality is going to be an important criterion in the negotiations that have just begun.

The hearings held by the European Parliament led both in 2004 and in 2009 to a rejection of the candidature of certain prospective commissioners for reasons associated with their personal profile or with the positions they adopted at the hearings. We cannot rule out the possibility that the MEPs may be tempted to act likewise with regard to the candidate to the presidency of the Commission if they judge that candidate to be insufficiently prepared to exercise the function.

The members of the European Council, for their part, will probably pay equally as much heed to the personal profile of the next president of the Commission. As in the past, it will fall to them to determine whether they wish the presidency of the Commission to be entrusted to a strong personality or to someone more amenable, in other words more acquiescent and easy to control, also in relation to the person whom they (alone) choose to play the role of permanent president of the European Council (see §4 below).

All in all, any potential animosity in the negotiations between the European Council and the European Parliament may have the effect of fostering the emergence of a candidate for the post of president of the Commission whose profile will be thoroughly examined, on the basis of the two or three criteria discussed below.

2.1. Competence

The president of the Commission should be chosen first and foremost on the strength of his ability to perform the functions described in Article 17 of the Treaty on the European Union, which specifies in particular that he "shall lay down the guidelines within which the Commission is to work" and that he "shall decide on the internal organisation of the Commission, ensuring that it acts consistently, efficiently and as a collegiate body".

In his capacity as a member of the college of commissioners, he must also meet the conditions laid down in the same article, which specifies that "the members of the Commission shall be chosen on the grounds of their general competence and European commitment from persons whose independence is beyond doubt".

An unwritten rule sometimes invoked consists in considering that in order for the president of the Commission to be able the better to perform his tasks as a whole, he needs to be perfectly fluent in his institution's two working languages, English and French.

Each person is free to judge the extent to which these criteria have been met in the past and to assess the extent to which they are likely to be met when the next president of the Commission is chosen.

2.2. The status: former minister or former Prime minister?

A rule that is enshrined neither in the treaties nor in any other official text has appeared to govern the designation of the last three presidents of the Commission; it consists in appointing people to the post who have held the post of prime minister. This was the case with Jacques Santer, with Romano Prodi and with José Manuel Barroso (see Table 5).

Can the recent creation of the post of permanent president of the European Council have influenced the application of this "custom"? This, possibly to encourage the heads of state and government to invoke it exclusively for the successor to its first incumbent, Herman Van Rompuy, in accordance with a desire to designate a former counterpart of comparable rank; or, on the contrary, to honour some kind of balance between the two functions of president of the European Council and president of the Commission, given that the latter is also an ex-officio member of the European Council and thus expected to have already been a member of that "club"?

On the political level, it is not certain that having systematically designated former prime ministers over the past twenty years has helped to attenuate the frequent reference to the "Delors presidency", despite the fact that that presidency was held by a figure who had been an economy and finance minister but not a prime minister. And we can also see that, apart from Jacques Delors' predecessor Gaston Thorn, none of the other presidents of the Commission had previously been prime ministers either.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

2.3. Gender?

All of the presidents of the Commission designated since the European construction process began have been men. While they probably were not chosen primarily on gender grounds, is it now out of the question that such a criterion may be invoked for the designation of José Manuel Barroso's successor?

An analysis of the most recent appointments to top European posts allows us to stress that the desire to permit women to play an increasingly important role is being expressed ever more strongly, especially by MEPs. For instance, it is worth pointing out that the heads of state and government took on board the wish to appoint at least one woman during negotiations for the previous renewal of the institutions in 2009. This wish appears to have carried a great deal of weight in favour of Catherine Ashton's appointment to the post of "high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy" and vice-president of the European Commission.

This precedent may suggest both that the gender of the candidate designated for the post of president of the Commission could be one of the factors taken into consideration by the European Council and European Parliament, but also that this criterion may prevail in at least one or other of the other European posts requiring to filled in the coming months (see §4 below).

3. A major criterion: the president of the Commission's country of origin

The choice of the president of the Commission is both a political and a diplomatic choice, in view of the European Union's dual legitimacy, evoked in particular by Article 10 in the Treaty on the European Union (the legitimacy of the citizens and the legitimacy of the governments).

In this connection, we should point out first and foremost that, in order to be designated president of the Commission, the prospective candidate first has, more prosaically, to be put forward by the government authorities of his or her own country of origin for a Commissioner's post, which tends to suggest that the candidate has to be more or less in tune with those government authorities' political leanings, or even with their party line[9].

On a more general level, Article 17.5 in the Treaty on the European Union states that members of the Commission must "reflect the demographic and geographical range of all the member states" in the hypothesis (ultimately never adopted) that the states should be represented on the Commission in rotation.

It is worth nothing that this desire for balance has also emerged during the designation of the presidents of the Commission over the past few decades, and that it has been able to cater for considerations at once demographic, geopolitical and historical.

3.1. The demographic aspect: the size of the country of origin

First of all, we can see that the function of president of the Commission has been assigned to nationals of countries of different sizes rather than systematically hailing from the EU's most populous countries (see Table 6). If we look at the countries of origin of the last six presidents of the Commission, we see that:

- three of them have come from a "large" country with a population of more than 25 million: Roy Jenkins (United Kingdom), Jacques Delors (France) and Romano Prodi (Italy);

- one of them has come from a "middling" country with a population of between 7 and 25 million, namely José Manuel Barroso (Portugal);

- and two of them have come from a "small" country with a population of less than 7 million (Gaston Thorn and Jacques Santer, both from Luxembourg).

If we consider the nationality of the other past presidents of the Commission, we will find the same kind of demographic balance over the years, given that three of them came from "large" countries (Walter Hallstein from Germany, Franco Maria Malfatti from Italy and François-Xavier Ortoli from France) while two of them came from "middling" countries (Sicco Mansholt from The Netherlands and Jean Rey from Belgium).

3.2. The geopolitical aspect: the location of the country of origin and its membership of the "hard core" of European integration?

An analysis of the geographical origin of the recent presidents of the Commission reveals a certain desire for balance, given that:

- three of them have come from countries in the west of Europe, namely Gaston Thorn (Luxembourg), Jacques Delors (France) and Jacques Santer (Luxembourg);

- two of them have come from countries in the south of Europe, namely Romano Prodi (Italy) and José Manuel Barroso (Portugal);

- and one of them has come from a country in northwest Europe, namely Roy Jenkins (United Kingdom).

This desire for balance also emerges if we consider the Commission's earlier past presidents, from the west of Europe (Walter Hallstein from Germany, Jean Rey from Belgium and François-Xavier Ortoli from France) but also from the south of Europe (Franco Maria Malfatti from Italy) and from a country (Sicco Mansholdt from The Netherlands) admittedly located in the west but politically close to the countries of northern Europe.

This list, however, reveals two striking absentees: the countries of northern Europe, despite the fact that they joined the EEC in the 1970s (Denmark) and in the 1990s (Finland and Sweden), and the countries of eastern Europe, although of course they joined far more recently (in 2004 and 2007).

An analysis of the appointments to the presidency of the Commission since the 1990s also hints at a practice which may not be codified in any official document but which appears to enshrine a kind of more or less explicit form of political jurisprudence. The practice in question consists in considering that the president of the Commission should preferably come from one of the countries most committed to European integration, in other words those that belong to the Schengen area and to the euro area. This unwritten rule has certainly been honoured in the case of the four people who have held the post of president of the Commission since those two forms of more advanced political integration have existed; conversely, it does not appear to have been considered essential in connection with the appointment to the post of high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy, which was first assigned to Spain's Javier Solana (and Spain is a member of both the Schengen and euro areas) and then to Catherine Ashton (whose country is a member of neither). This unwritten rule is likely to be invoked once again in the course of the negotiations currently taking place, especially in view of the lively debate triggered by both of these milestone achievements in the European construction.

3.3. The historical aspect: length of membership of the member state of origin

And lastly, we can see that the role of president of the Commission has been assigned to nationals from countries that have been members of the EEC or of the EU for a greater or a lesser length of time:

- four of them have come from one of the founder members of the European construction process: Gaston Thorn (Luxembourg), Jacques Delors (France), Jacques Santer (Luxembourg) and Romano Prodi (Italy);

- one of them has come from a country that has been a member of the European construction process for less than twenty years, namely José Manuel Barroso (Portugal);

- and finally, one of them has come from a country that had joined the European construction process less than five years before, namely Roy Jenkins (United Kingdom)[10].

In view of the above, we may wonder whether the European Council and European Parliament may not shortly feel the desire to issue a signal of the same kind as the one they issued after the enlargement of 1973 by appointing a national from a new member state. We can certainly argue that the appointment of former Polish Prime minister Jerzy Buzek to the post of president of the European Parliament in 2009, for example, can very possibly have been read as a symbolic signal of that kind. Could an appointment of the same kind soon be made to the post of president of the Commission, or are we more likely to see that signal being issued in connection with the other European posts to be filled, namely the post of president of the European Council or that of high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy (see §4 below)?

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

* This description reflects the countries' demographic situation based on the following scale: "Large" = a population of more than 25 million / "Middling" = a population of 7 to 25 million / "Small" = a population of less than 7 million.

** With reference to the date on which the agreements were signed (14 June 1985 in France's case).

4. From an MCQ to Rubik's cube: the impact of designations to other European and international posts

The choice of the president of the Commission is not just a choice based on the numerous political criteria mentioned above (see Parts 1 to 3), it is also a choice that is made in a specific institutional and diplomatic context, which it is crucial that we review before concluding.

The designation of the president of the European Commission has traditionally been negotiated in a broader political framework, including in particular the election of the president or presidents of the European Parliament (a rotating system with a change in mid-mandate has prevailed hitherto). Since the Treaty of Lisbon came into force, it has also been associated with the appointment of two other leading European officials, namely the president of the European Council and the vice-president of the Commission / high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy. This new situation may well transform the negotiations over the designation of the president of the Commission, which is beginning to look less like a "multiple-choice question" and increasingly like a "Rubik's cube" [11].

4.1. Allowing for the other European posts to be assigned

In addition to the post of president of the Commission, which theoretically needs to be filled by July 2014, several other European posts are due to be assigned over the coming weeks and months:

- the post of president of the European Parliament, as of June 2014;

- the post of vice-president of the Commission / high representative of the Union for foreign affairs and security policy, after the summer recess of 2014;

- the post of president of the European Council, in the autumn of 2014;

- the post of president of the Eurogroup in 2015[12].

It is highly likely that the members of the European Council and of the European Parliament will build all of these appointments into their negotiations, and that they will also peg each one of these appointments to the three main criteria identified above, namely the party affiliation, personal profile and country of origin of the prospective or proposed candidates (see Table 7). There can be no doubt that this multi-faceted approach can only complicate both the substance and the outcome of those negotiations.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

* This description reflects the countries' demographic situation based on the following scale: "Large" = a population of more than 25 million / "Middling" = a population of 7 to 25 million / "Small" = a population of less than 7 million.

4.2. Posts already held in other European and international organisations?

Lastly, the choice of the president of the Commission needs to be set in an even broader institutional and diplomatic context, which also includes posts already held by one or the other member-state national in a number of European or international institutions.

For instance, the fact that an Italian national (Mario Draghi) is already the president of the European Central Bank makes it unlikely (though not impossible) that an Italian national will be appointed to the post of president of the Commission. By the same token, José Manuel Barroso's succession is unlikely to go to a Portuguese national in view of the desire for a diplomatic balance capable of being expressed in geographical space as well as in time.

All in all, a brief overview of the negotiations that have led to the designation of past presidents of the European Commission suggests that the nationality of the incumbents of four or five other European[13] and international posts could be considered an issue in the negotiations currently under way and could have some kind of influence on both their conduct and their outcome (see Table 8).

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

* Jens Stoltenberg was nominated on 28/03/2014 to succeed A.F. Rasmussen. He will be taking up his post on 01/10/2014.

** The geographical rotation expected for this function could lead to nominate a European to succeed Ban Ki Moon.

Conclusion: on the need for a clear choice

The choice of the next president of the European Commission is likely to be made in part on the basis of his or her party affiliation and, as in the past, it is going to have to reflect the majority coalition that has formed in the European Parliament if it is to win that assembly's endorsement. In this connection, the MEPs who stood as candidates for the large European parties in the recent elections have a major card to play, of course, on condition they continue to enjoy their parties' support till the end. But the choice of the president of the European Commission is also going to depend, as in the past, on other political criteria such as the stated or prospective candidates' personal profile, their national origin, or even diplomatic negotiations addressing also other European or national appointments coming up for renewal in the coming weeks. All of these factors and criteria have their own intrinsic legitimacy, which it is worth recalling in order to ensure that the joint choice of the European Council and of the European Parliament is made in a situation of clarity, at the outcome of negotiations which will determine the extent to which one or other factor has prevailed.

Having stressed the importance of the need for clarity, that clarity also needs to apply not only to the substance of the negotiations but also to the manner in which those negotiations are conducted. In this connection, the principles of "openness" and "transparency" mentioned in Articles 10.3 in the Treaty on the European Union and 15.1 in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union should ensure that both the debates and their attendant voting sessions in the European Parliament and in the European Council are public. The European Parliament's vote of approval of the president of the Commission was by roll call until 2004, but it was not in 2009, so that it was impossible to find out exactly who voted in favour of assigning José Manuel Barroso a second mandate. It is up to the newly-elected MEPs to return to the earlier practice by changing the European Parliament's internal regulations (which they are due to adopt in the coming weeks) accordingly. It is also up to them to call on the heads of state and government to ensure that the "necessary consultations" between the European Council and the European Parliament provided for by Declaration No. 11 annexed to the Treaty on the European Union are also held in a transparent environment, including within the European Council.

If the next president of the European Commission enjoys all of the legitimacy that he or she is going to need to fulfil his or her functions and be able the better to address the countless political challenges currently facing the European Union, it will also be because he or she will have been chosen in clear, transparent and democratic circumstances.

Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/fr/004a50d310/Composition-du-Parlement.html; layout and calculations by Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/fr/004a50d310/Composition-du-Parlement.html; layout and calculations by Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé.

NB: EPP = European People's Party / ALDE or EDLR or ED or LDR or ED or L = Liberal and democrats / S&D or PES or S = Socialists and Democrats / GUE/NGL or CG or COM = Radical left or communists

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé

Source: Yves Bertoncini, Thierry Chopin, Claire Taglione-Darmé

NB: The political affiliations given are those of the heads of government at the time of the European elections and of the designation of the president of the Commission

* In 1994, France had a Socialist president of the republic but a right-wing prime minister, while in 1999 the opposite was true: here we take the president's party affiliation into account.

** ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists / EL: Party of the European Left / N.A.: Non-attached / EPP: European People's Party / PES: Party of the European Socialists / ALDE or EDLR: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe or European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party.

[1] On this issue, see Yves Bertoncini and Thierry Chopin, "Faces on divides: the May 2014 European elections", Studies & Reports No. 106, Notre Europe - Jacques Delors Institute and Robert Schuman Foundation, April 2014.

[2] The European Parliament has had the power to approve the president of the Commission since the Maastricht Treaty came into force, in other words since 1994; yet Jacques Delors won just such a vote of approval when he took office at the start of 1985 and again when he received his second mandate in 1990.

[3] The other figures designated to become members of the Commission are also heard by the European Parliament after being nominated by the Council, "in agreement with the president of the Commission". They are subjected to a collective vote of approval, yet that vote was subjected to the review of one or other prospective candidate in 2004 and in 2009 at the request of the political groups in the European Parliament.

[4] On this issue, see António Vitorino, "European Commission and Parliament: what relations?", Tribune, Notre Europe - Jacques Delors Institute, January 2014.

[5] It is worth pointing out that the European Parliament's votes of approval for the president of the Commission and for the college of commissioners have only been separate since the adoption of the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1997.

[6] We should note that this list does not include vice-president of the Commission Manuel Marin (PES), who took up the post of acting president for a six-month period in 1999 following Jacques Santer's resignation.

[7] Walter Hallstein (EPP) was president of the European Commission from January 1958 to July 1967; Jean Rey (ELDR) from July 1967 to June 1970; Franco Maria Malfatti (EPP) from July 1970 to March 1972; Sicco Leendert Mansholt (PES) from March 1972 to January 1973 and François-Xavier Ortoli (Gaullist) from January 1973 to January 1977.

[8] A blocking minority of at least 92 votes can thus include two "large" countries (for instance the United Kingdom and Italy), three "middling" countries (for instance Hungary, The Netherlands and Sweden) or one "smaller" countries (for example Denmark or Finland).

[9] We should note that there have been certain exceptions to this rule in the past, for instance with the renewal in his capacity as European commissioner (and thus as president) of José Manuel Barroso by a Portuguese Government led by the Socialist party.

[10] The five previous presidents of the Commission all inevitably came from founder members of the European construction process in view of the date of their appointment (unless it had been decided to appoint a Briton, an Irishman or a Dane the very year their countries joined, namely 1973).

[11] According to an expression borrowed from Hugo Brady (Centre for European Reform) and his Tribune dated April 2013: "The EU's Rubik's Cube: Who will lead after 2014?".

[12] The European governments and Parliament would consider the appointment of the next president of the Eurogroup to be even more strategic if it were full-time, along the lines of that of the president of the European Council.

[13] The nationality of the presidents of other European institutions, for instance the Court of Justice, could be invoked if the case were to arise, but it does not look as though it is going to have a decisive impact on the negotiations currently under way.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Freedom, security and justice

Jean Mafart

—

15 April 2025

Asia and the Indo-Pacific

Pierrick Bouffaron

—

8 April 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Radovan Gura

—

25 March 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Stéphane Beemelmans

—

18 March 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :