Democracy and citizenship

Magali Balent,

Corinne Deloy

-

Available versions :

EN

Magali Balent

Corinne Deloy

Introduction

: An IFOP survey on 4th April 2014 undertaken in France credits the National Front (FN) with 22% of voting intentions in the European elections of May next placing it second behind a Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) (24%) but ahead of the Socialist Party (PS) (19%); a forecast result that is five times higher than five years ago. In Austria a survey by Unique Research on 4th April 2014 forecasts 19% of voting intentions for the FPÖ, whilst a YouGov survey on 6th April 2014 in the UK credits UKIP with 40%.

In a depressed economic and social context, which has weakened the European Union in the eyes of its citizens and in a time when identity issues are highly present in public opinion, the scenario of a rise by the far right in the European Parliament is taking shape and seems to be an increasingly credible possibility.

If this perspective becomes a reality after the vote, will these parties have the means however to bring their weight to bear in the Assembly in Strasbourg and as a result will they represent a detrimental counterweight for the European Union? This question implies that they will succeed in agreeing together as one group - which they have not managed to do until now.

After a brief analysis of what unites and distinguishes the European far right parties from an ideological and historical point of view we shall discuss the outlook for these parties after the European elections.

I - The far right in Europe: United in Diversity?

1) A discourse of opposition to the European Union which is riding on an identity crisis

- The European far right boosted by ambient euroscepticism

The parties which are classed as being far right share the same idea of the European Union which they unequivocally qualify as an ineffective organisation that is responsible for the economic decline of its Member States. The euro is seen as the first culprit in this European economic shipwreck, as the far right parties claim is proved by the fact that the euro zone has the weakest growth rate and the highest unemployment level in the world. This is why some parties see the exit of the euro as the only solution to saving their country from bankruptcy. Two Northern League members, Matteo Salvini, Federal Secretary and Claudio Borghi Aquilini, joined forces to publish a book entitled Basta Euro in 2014 in which they explain why the return to a national monetary policy is necessary, in their opinion, to save Italy from ruin and to respond to the population's requirements in terms of employment - they also accuse the euro of being behind the destruction of thousands of industrial jobs[1].

In addition to this the European Union is seen as a dictatorial tool in the hands of the most powerful European States, and more particularly Germany, which stands accused in this instance of dictating its demand, recalling the anti-German feeling that is a constant feature amongst several far right parties. For the Northern League the European Union is "the property of the Germans, French and the big bankers"[2] whilst the FN maintains that the main task is to defend "France's freedom from European demands set out by the Germans and in their wake American imperialism[3]." In a recent interview given on the Vlaams Belang site, Geert Wilders, leader of the Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands said that he did not want his country to continue its submission to the European Union's "diktat"[4]. In particular these accusations target the free trade agreement that is under discussion between Europe and the USA as well as the "European austerity contracts that Ms Merkel's Germany wants to force upon countries in the euro zone." [5]

Finally the European Union is seen as a structure whose reason for being is to dismantle the nation-states. The FN speaks of an "anti-national steam roller"[6] as it stigmatises in particular the opening of the borders which is said to introduce unfair competition between the States by reducing salaries and threatening national identities as they face other cultures deemed incompatible with the host culture. But this development is seen as an imposture since - as the FPÖ's programme explains - "the future of Europe must lie in the free organisation of its States" and because the "aim of European integration is to rally a community of States which form Europe geographically, spiritually and culturally, and which are united by western values, cultural heritage and the traditions of European people."[7] In the minds of the far right parties the European Union can only be based on a confederation of sovereign States which have a common origin and belong to the same area of civilisation. Any other form of organisation is but the product of a dark conspiracy on the part of the elites to destroy the nations and their populations in an attempt to build a globalised, borderless area on the ruins of this. This is why it is vital for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) to return the sovereign power to the country, notably regarding the control of its national borders, by quitting the Union[8]. Hence quite paradoxically withdrawal into the national protective cocoon seems to offer a miracle solution to the challenges of a world that is constantly opening up.

In many respects the positions and arguments put forward by the parties might seem simplistic - simplifying the real, reducing European power struggles to the confrontation of two irreconcilable camps - those who support sovereignty on the one hand and the internationalists on the other. And yet in a context of growing euroscepticism fed by the economic and financial crisis, and by the European Union's inadequacies, the far right discourse is succeeding in its bid to convince a public which is disenchanted, which no longer believes in the proposals made by traditional parties and mistrusts the European project which they no longer understand. The concerns and worries of the populations match up with those set out by the far right. The most recent Eurobarometer survey published in December 2013 indeed highlighted a downturn in the Union's image, which was positive for only 31% of those interviewed whereas they totalled 48% in the spring of 2008. Moreover 66% believe that their voice does not count in Europe and 43% say they are pessimistic about the Union's future[9]. It is easier to understand why the discourse used by the extremists convinces public opinion that has been weakened and as a result is more receptive. According to the FN's image barometer undertaken in February 2014 by TNS Sofres the rate of approval of the FN's ideas is said to be 34%[10] !

- The European far right unified in the same obsession with identity

The far right parties also agree on political and societal stakes in that they systematically reduce theses to a problem of identity. The defence of the nation's identity is indeed the final goal of their political programme, which they define according to ethno-cultural criteria rather than political ones. The survival of the nation depends therefore on its ability to protect is ancestral heritage - historic, cultural, ethnic - and to maintain its specific identity which is unique and eternal. Hence any change to that heritage via the integration of populations deemed to be culturally incompatible inevitably leads, according to these parties - to the death of the nation. This is why overall they see immigration and the "multicultural drift" of their nation as a major cause of the denaturation of identity. The FPÖ says however in its programme that "only immigrants who speak German, who know our values and our laws and who share our culture may remain in the country and request Austrian citizenship."[11] Some of these parties which moderate their discourse in a bid to de-demonize themselves all share the same view, in that they do not condemn immigration as such, but only non-European immigrants, whom they believe incapable of integrating the nation.

This is why these parties identify immigration from Muslim countries - which is now the main source of non-European immigration in the countries of Europe - as the main threat. This focus on the Muslim threat, stimulated by 9/11 and the rise of radical Islam, finds particular expression in the north of Europe which was for a long time void of any type of immigration - like the Netherlands - where the "debate focuses on Islam's compatibility with the fundamental principles of the Dutch conception of living together: "freedom of expression, religious pluralism, separation of the State from the Church, gender equality[12]." In Norway - a confessional State and a non-EU member, where 86% of the population adheres to Lutheran Protestantism, Muslim immigration is creating tension - not on the job market in a country where unemployment is the lowest in Europe, but within society. Hence the Progress Party which is a government member, lambasts "Muslim demands which come one after another: halal food in prison, religious holidays, separate gym classes," insinuating that the Muslim minorities might bring about deep changes to Norwegian identity[13]. This obsession with the Muslim threat is not particular however just to the extreme parties in the North of Europe. Indeed during the French Presidential campaign in 2012, Marine Le Pen compared "street prayers" which take place in certain urban suburbs to a "foreign occupation" or maintained that the rise of "cathedral mosques" was a breach of secular laws.

Again, it has to be admitted that this discourse works and convinces because it finds an echo amongst European populations - well beyond the traditional circles of the far right. The themes developed are deemed vital in the eyes of a growing share of European citizens. The political sentiment barometer published at the start of every year by the CEVIPOF in France provides some information in this regard: in January 2014 67% of the French interviewed (in comparison with 49% in December 2009) maintain that there were too many immigrants in France[14]. The IPSOS survey on "new French cleavages" published in January 2013, shows that 74% of those interviewed believe that the Muslim religion is not compatible with the values of French society, 80% believe that it is trying to impose its way of functioning on others[15]. An MPI study (Migration Policy Institute) published in May 2013, highlights the same fears on a more overall European level and maintains that Muslim integration has been a major debate in European countries since 9/11. Hence a majority of Europeans feel that Muslims have not managed to integrate and will inevitably transform the religious and cultural landscape of the countries of Europe[16].

However the same stigmatisation of the European Union and the same declared concern about the denaturation of the identity of their nation should not hide the fact that these parties do not form a united block, either from an historic or ideological point of view.

2) Deep Ideological and Historical Divergence

- Specific heritage anchored in particular national features

Firstly the "family" of European far right parties has extremely diverse origins. Some parties are the legacy of the traditional, most radical far right, which adopts an ideological and historical continuity with fascism and racial theses: this is the case of the Swedish Democrats, direct legatee of "Let's Keep Sweden Swedish" (BSS) which adhered to neo-Nazi values; it is the case of the FN of the 1970's founded by former Vichy members and those nostalgic of the Third Reich or the Party for a Better Hungary (Jobbik), which took up the flag used by the Hungarian Fascists (Arrow Cross Party) as soon as it was formed; there is also the British National Party (BNP) formed in 1982 by John Tyndall, a former Nazi. Other parties orient themselves rather more to a modern far right, focusing from the beginning on anti-taxation and anti-immigrant issues: this was the case of the Norwegian Progress Party created in 1972 or the Vlaams Belang (VB) in Belgium. Finally others did not originate in the far right but in the conservative or liberal right. The Danish People's Party (PPD) founded in 1996 after the scission of the liberal Progress Party and the Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands which was born of the Liberal and Democratic People's Party in 2004 and also the Democratic Centre Union (UDC) in Switzerland, which defines itself as "morally conservative and economically liberal" illustrate this latter category.

These multiple origins linked to national specific features, in which these nationalist parties find root, determine the major differences that exist between those which express a "völkisch" type of nationalism - defining the nation as a blood community set in a biological substrata, from those who embrace a more political nationalism within the nation-states, welded together by a common political consciousness. In Greece, where national identity has remained set in the past and where there is now massive illegal immigration from Turkey (equal to 90% of the illegal flow entering into the EU), Golden Dawn adopts a programme which defends a "new type of man" and defines the people as "a qualitative sum of men who share the same biological and spiritual heritage."[17] However nothing like this is to be found in the discourse of Marine Le Pen's FN, as she has aimed to normalise her approach and since 2006 - the date she became her father's campaign director in his presidential bid of 2007 - has transplanted a Republican element onto the FN's former nationalist discourse. The discourse of Valmy as expressed by Jean-Marie Le Pen in this context illustrates this ideological development as he addresses "the French of foreign origin" inviting them to "melt into the national and republican crucible with the same rights but also the same duties[18]." In the UK Nigel Farage's UKIP also sees immigration as a political danger and advocates only allowing immigrants who can support themselves financially and who can prove they are affiliated to a social security system access to Britain[19].

- Varied ideological positions

In terms of their programme positioning, the far right does not always stand as a block. Hence, whilst some parties focus on identity issues others devote more time to economic problems. The former typifies the Scandinavian parties rather well, whilst the latter defines rather more the parties in Southern (France, Italy) and Central Europe (Austria), with the countries of Eastern Europe illustrating a more composite profile The identity crisis is particularly salient in Scandinavia marked by what Erwan Lecoeur calls "prosperity extremism"[20], which also typifies the Netherlands and Switzerland, a non EU member. This form of extremism is the rule in wealthy, prosperous countries deemed to be open and tolerant. Here there is no mass unemployment nor is there a real downturn in living standards, but there is fear on the part of these homogenous, hermetic societies that with a new inflow of economic immigrants and political refugees from different cultures, they will lose their soul and their specific cultural features. The extremist parties have therefore focused their arguments on the dangers of migration since the beginning of the 1990's, accusing it of weakening the foundations of the Welfare State that is constitutive of Scandinavian societies; they claim it threatens the homogeneity of national identity, whether this is "danskhed" (Danishness) or "Finnishness" and that this will lead to a "multicultural drift"[21]. The economic and social cost of immigration has greater profile, likewise economic themes in general in the discourse of the FPÖ, the Northern League and the FN. Without relinquishing identity issues their discourse focuses on economic issues, turning directly towards those populations, weakened by the crisis and excluded from the benefits of globalisation, which until now had been rather more convinced by the discourse on the left. This is how the FN won recent local elections in March 2014 in France, claiming several town halls in working class or popular areas (Hénin-Beaumont, Villers-Cotterêts, Hayange, Beaucaire) which are marked by high unemployment and poverty beyond the national average. This did not prevent Marine Le Pen on a visit to Beaucaire in February 2014 from reviewing the issue of identity by declaring "I like going to Rabat [...] but when I come to Beaucaire I don't like feeling that I'm in Rabat[22]."

Moreover, although the anti-Islamic dynamic rallies the parties in Western Europe in the same criticism of "the creeping Islamisation of European societies" this does not apply to the same parties in Eastern Europe which are not confronted by mass immigration from Arab/Muslim countries[23]. However these countries are the theatre of typified ethnic overlapping and as a result, of high tension regarding ethnic minorities - especially Jewish, gypsy and Roma minorities. Hungarian Jobbik's discourse is quite enlightening in this sense. As part of Hungary's policy to open up to the east it expresses real sympathy for the Muslim world whose resistant attitude it lauds as far as globalisation is concerned, preferring to focus its attacks on the Jewish members of the Hungarian Parliament, "who are danger for the national security of Hungary" and also "gypsy delinquency"[24]. This divergence reminds us that these parties remain fundamentally nationalist and as a result focused on national issues which govern their discourse. Hence, whether it concerns an anti-immigrant or anti-minority discourse, the parties on the far right always designate a main enemy, described as a danger to the nation and its survival. In sum the triggers remain the same.

In these conditions is the perspective of the formation of a parliamentary far right group after the elections in May 2014 for the 8th legislature of the European Parliament credible?

II - The Far Right in the European Parliament: a gain in ground forecast

In 1994, the vote in support of the far right totalled 7.7%; ten years later it rose to 8.1% - a record to date - and 6.6% in 2009. These results can be explained in part by the proportional voting method used to appoint MEPs, which leads in effect to a more acute expression on the part of the discontented.

The results of the most recent elections in the Member States and the surveys show a rise in mistrust of the European Union: the far right parties may make a breakthrough in the next European elections. Hence they might be amongst the leaders in this election in France (FN) and the UK (UKIP), or win a great many votes in Austria (FPÖ), in Greece (Golden Dawn), in Italy (Northern League), in Finland (True Finns) and the Netherlands (PVV).

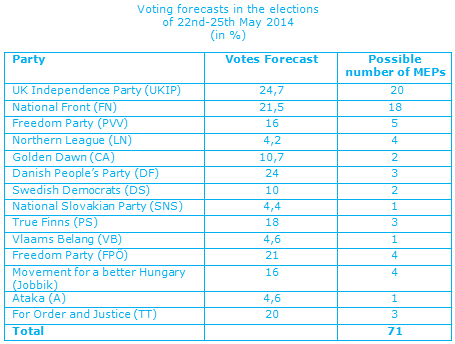

The European elections on 22nd-25th May next may lead to a rise in the presence of the far right in the parliament in Strasbourg. According to forecasts, just two months from the election, this political trend might enable them win around 30 extra seats (there are 47 of them at present). Because although many parties are due win more seats, the 12 Member States which are likely to send far right MEPs to the European Parliament are "small" countries which have a small number of seats (13 seats for Slovakia, Finland, Denmark; 17 for Bulgaria; 18 for Austria). Amongst these only France, UK and Poland have more than 50 seats in Strasbourg. According to the polls in France the FN might win 15 seats (ie five times the number it has today); UKIP may double the number of MEPs it has (from 9 to 20). The PVV may win 5 seats in the Netherlands, the Northern League, Jobbik and the FPÖ four seats each and the Danish People's Party (DP) and For Order and Justice (TT) in Lithuania 3 (see annex).

The decision on 26th February last taken by the German Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe to do away with the obligation for a party to win at least 3% of the vote to have seats in Strasbourg may also enable the National Democratic Party (NPD) to enter the European Parliament.

1) A divided group in search of integration

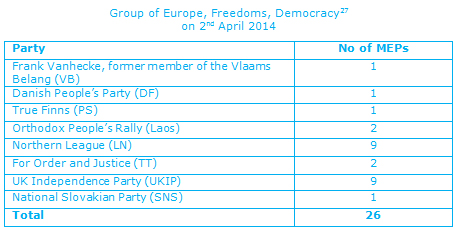

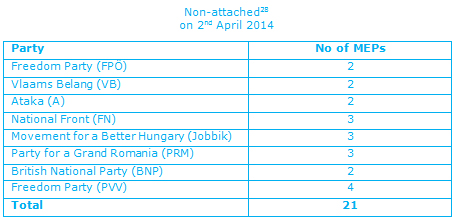

The 47 far right MEPs are a heterogeneous set divided into two groups in the European Parliament at present: 26 belong to the Europe, Freedom and Democracy group (EFD) whilst 21 are non-attached. Their lack of cohesion and therefore their inability to form coalitions is a handicap to them to a certain extent within an institution that mainly functions on the basis of negotiation and compromise.

In November 2013 several parties (PVV, FPÖ, FN, Vlaams Belang, Swedish Democrats and the National Slovakian Party (SNS)) decided to join forces in view of the European election in May 2014 so that they could form a group in the future parliament. This union raised many questions because of the ideological differences, some of them major that exist between these different parties. Although all of them want their country to leave the EU and are firmly against immigration they differ on several issues, for example, the relationship with Israel or homosexuality (the FN opposes the PVV which supports the Jewish State and favours same sex marriage). On 7th December 2013 the members of several of these parties met in Vienna on the invitation of the FPÖ under the banner "A Free Europe".

The True Finns (PS) and the Danish People's Party which are more liberal criticised the rapprochement of these far right parties. UKIP refused a priori any form of alliance with them.

In order to be able to form a group in the Strasbourg assembly the far right parties will have to rally a minimum of 25 MEPs from at least one quarter of the Member States (ie 7). A parliamentary group would enable them to have greater influence in the debates and defend their ideas better. They would also have speaking time according to their size as well as the means allocated to any group by parliament: co-workers, offices, a secretariat, translation and communication budgets.

2) An impossible union?

On several occasions the far right has tried to rally in the European Parliament. Between 1984 and 1989 the group of the European Right, led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, rallied 17 MEPs from four parties. Dissolved in 1989 the group of the European Right took over from 1989 to 1994 (17 MEPs from three member states) again led by Jean-Marie Le Pen. Finally in January 2007 Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty rallied 23 MEPs from 7 countries but the group was dissolved after just a few months following dissension between Social Alternative (AS) and the Grand Romania Party (PRM).

It is therefore difficult for the nationalist parties to unite on a supranational level. "On a European level the eurosceptics are not really the sum of their parties," indicated Paul Taggart, a lecturer on political science at the University of Essex. On the Vote Watch site, which publishes data on MEP attendance, votes and activities, we see that the rate of participation and especially cohesion between far right MEPs is lower than amongst other parties in Parliament : 48.9% on average for Europe, Freedom and Democracy (EFD) in comparison with 83.1% on average (94.6% for the Greens/European Free Alliance (EFA) and 92.5% for the European People's Party, EPP). The far right parties each have their own agenda; their votes differ in many instances and they only agree on some specific issues like immigration and European integration. Their division, disorganisation and their lack of discipline and common position on the future of Europe prevents them from agreeing on a political programme.

A few weeks ago the nationalist parties indicated that they would not present a joint candidate for the presidency of the European Commission. The Lisbon Treaty makes it obligatory for the European Council to take on board the results of the European elections when it chooses the person it wants to see in the post of President of the Commission; the Council's candidate will then be subject to a vote by MEPs[25]. "We are not abstaining from putting a candidate forward because we lack competent people but because we do not want to deceive the citizens. There is not one European list or European candidate for whom people can vote. It is just a recommendation that the Council is not forced to follow. We do not want to take part in this false, dishonest democracy," declared MEP Franz Obermayr (AT, FPÖ) in justification of this choice[26]. It seems however that there were battles of ego which effectively prevented the appointment of a candidate.

The vote in support of the far right in the European elections, and the wish on the part of this political trend for union are not new. However the ability of some of these parties - due to the development in their ideological positioning (social and protectionist discourse and defence of the Welfare State and the principles of living together in Europe - tolerance, freedom of expression, gender equality, women's emancipation, pluralism, secularism etc ) - to federate the discontented has not been achieved to date. Moreover the more pragmatic approach of these parties, which are seeking power, might enable them to quash some of their ideological dissension as they place value on the things that do bring them together.

An increase in the number of MEP seats they win in the next European elections in May could encourage the far right parties to become more involved in the parliament in Strasbourg which they use more often as a stage to express their opinion and oppose each other rather than a area of work and proposal.

The probable rise of the far right, a consequence of the dispersion of votes, which is usual in the European elections, should not however lead us to overestimate their effect on political balances in the future European Parliament. However it would force the European People's Party (EPP) and the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and even the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), as well as the Greens/European Free Alliance (EFA) to form large coalitions more frequently in order to obtain the majority.

Annex

Source : Internet Site Pollwatch

Source : Internet Site Pollwatch

(http://www.electio2014.eu/fr/pollsandscenarios/polls#country)

[1]Claudio Borghi Aquilini, Come uscire dall'incubo. 31 domande 31 risposte. La verità che nessuno ti dice, Lega Nord, Febraruy 2014, http://www.bastaeuro.org/docs/BastaEuro_comeusciredaincubo.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] New Year's Greeting by Mr. Le Pen to the press, 7th January 2014,http://www.frontnational.com/videos/voeux-de-marine-le-pen-a-la-presse/

[4] G. Wilders, "We are all Flemish!", 2nd March 2014, http://www.vlaamsbelang.org/interviews/33/

[5] op.cit.

[6]Quoted in Le Figaro, 27th January 2014, http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2014/01/27/97001-20140127FILWWW00398-le-fn-a-l-ambition-de-bloquer-l-ue-philippot.php

[7] FPÖ Programme, adopted during the party's congress on 18th June 2011, http://www.fpoe.at/fileadmin/Content/portal/PDFs/_dokumente/2011_graz_parteiprogramm_englisch_web.pdf , p. 17.

[8] UKIP Programme, http://www.ukip.org/issues

[9]Standard Eurobarometer 80, http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb80/eb80_first_fr.pdf

[10]Baromètre d'image du Front national, February2014, http://www.tns-sofres.com///sites/default/files/2014.02.12-baro-fn.pdf

[11]Op.cit., p.5

[12] C. de Voogd, " Pays-Bas : la tentation populiste ", Note de la Fondapol, May 2010, p. 21.

[13] On this issue see S. Kovacs, " L'immigration commence à être perçue comme un danger ", Le Monde, 28th July 2011.

[14]Le baromètre de la confiance politique, survey undertaken by CEVIPOF, Wave 5, January 2014, http://www.cevipof.com/fr/le-barometre-de-la-confiance-politique-du-cevipof/les-resultats-vague-5-janvier-2014/ , p. 55.

[15]France 2013 : Les nouvelles fractures, survey undertaken by IPSOS and CGI Business Consulting, January 2013, http://www.ipsos.fr/ipsos-public-affairs/actualites/2013-01-24-france-2013-nouvelles-fractures

[16] M. Benton and A. Nielsen, "Integrating Europe's Muslim Minorities : Public Anxieties, Policy Responses", Publications by the Migration Policy Institute, 10th May 2013, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/integrating-europes-muslim-minorities-public-anxieties-policy-responses.

[17] Quoted in the section "Identity", Golden Dawn site, http://www.xryshaygh.com/

[18] Quoted by S. Crépon, Enquête au cœur du nouveau Front national, Paris, Nouveau Monde éditions, 2012, p. 175.

[19] UKIP Programme on line, op.cit.

[20] E. Lecœur, Dictionnaire de l'extrême droite, Paris, Larousse, 2007, p. 18.

[21] On this issue see the article by Antoine Jacob, " L'Europe du Nord gagnée par le populisme de droite ", Politique Internationale, n°127, Spring 2010, pp. 221-238.

[22] Quoted in G. Mollaret, " A Beaucaire, on n'est pas au bled ", Le Figaro, 1st April 2014, p. 9.

[23] The 2011 Report by the Pew Research Center indicates that the Muslim population in the countries of Eastern Europe (matching the new EU entrants after 2004 except for Malta, Bulgaria and Croatia) represent less than 0.5% of the national population. "The Future of the Global Muslim Population", Pew Research Center, January 2011, http://www.euro-muslims.eu/future_global.pdf , p. 132.

[24] Collated by C. Léotard, " Une extrême droite qui n'exècre pas l'islam ", Le Monde diplomatique, April 2014, p. 7.

[25]Article 17, paragraph 7 of the Treaty on European Union stipulates: "Taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for President of the Commission. This candidate shall be elected by the European Parliament by a majority of its component members. If he does not obtain the required majority, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall within one month propose a new candidate who shall be elected by the European Parliament following the same procedure."

[26] Internet Site of the European Alliance for Freedom http://www.eurallfree.org/?q=node/1465

[27] Only far right parties are indicated here.

[28] Only far right parties are indicated here.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

On the same theme

To go further

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Ménégaux

—

2 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Jean-Dominique Giuliani

—

25 November 2025

Strategy, Security and Defence

Amiral (2S) Bernard Rogel

—

18 November 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :